Looking for Crime in All the Wrong Places

Looking for Crime in All the Wrong Places

appeared in Red Herrings, the magazine of the Crime Writers Association.

The past is fertile ground for crimes.

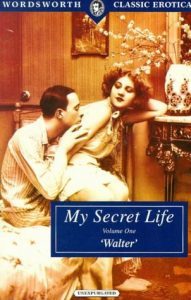

It’s worth seeking unusual sources. I found crimes in the dirtiest book I have ever read. “Doing your ‘research’ again?” says my wife, glancing over my shoulder at My Secret Life.

Every year, at CrimeFest, somebody raises “the Midsomer Problem”. How are there so many more crimes in fiction than in life? In St. Mary Mead, in Oxford, in Iceland? In the Faeroe Islands! Luckily for historical novelists, the past throngs with unexplained deaths. Judith Flanders’ The Invention of Murder shows how the modern conceit of ‘murder’ evolved, through public trials, burgeoning individual rights, and cheap sensationalist newspapers: rich sources for Victorian crime writers.

People are always offering writers ideas. You know the patter: “You’re a writer, eh? Here’s an idea for you… Send me the royalties when the film comes out.” Non-writers don’t realise it’s the structure that takes time: actual chapters, words in the right order. “I could write a book, you know.”

“Bugger off, then,” I mutter, “and write it.”

Yet somewhere we stumble on our ideas. We are always seeking the game-changing twist.

Newspapers. Pamphlets. Journals. Linda Stratmann uses The Illustrated Police News to illuminate society’s underbelly. Modern writers spin tales off Victorian classics: intertextual experiments with the Brontes and Dickens. Gothic sensibilities still inspire page and screen. Sensation fiction still casts its spell. The British Library republished early detective novels. Real life detective McLevy delights listeners in David Ashton’s stories.

Yet how to hear their authentic voices? Their secrets, free from censorious moralising? To hear “those most mysterious of mysteries, the mysteries which are at our own doors” (Henry James, praising Wilkie Collins).

I’ve unearthed crimes in intriguing places.

Henry Mayhew interviewed street folk, capturing japes, crimes and slang. Try his ‘Narrative of a Pickpocket’ in London Labour and the London Poor; or the grimy account of the ‘Traffic in Foreign Women’. From Lee Jackson’s original sources on VictorianLondon.org I filched a policeman’s tale of a counterfeit ring, spicing it with John Camden Hotten’s Dictionary of Slang.

More shocking than obvious crimes, however, are injustices casually recorded in memoirs and trashy literature. Where can you overhear conversations, clandestine thoughts, improper liaisons and backstreet rendezvous? In erotic literature.

The threat of ruination shadows Victorian characters, from Jane Eyre via Lady Audley to Dorian Gray. Yet in ‘literature’ it is never described as plainly as in Rosa Fielding, Victim of Lust, or Madame Birchini’s Dance by ‘Lady Termagent Flaybum’.

When Dorian Gray goes to the bad, what is he up to? When Doolittle sells Eliza, is it unusual? When Jekyll regrets Hyde’s dark urges, when Steerforth corrupts Little Emily, what are they doing?

Look no further than Walter’s My Secret Life. Walter goes further. Darker. Deeper. This eleven volume erotic memoir is not the best-written book you will ever read, not the most entertaining, nor the most erotic. But it is stuffed full of life, a scintillating social history by a remarkable mnemonist. Judith Flanders confesses qualms about researching this epic of debauchery, but she cannot resist his eye for detail. And details are the stuff of fiction.

Walter is cursed with memoriousness. He describes where he followed women, where he took them, chamber pots and bedsteads, petticoats and drawers, hairstyles, faces, and other parts of the anatomy, in extraordinary detail. There is no better guide to Victorian costs: wine, food and women. Where Mayhew sermonises on trafficking in foreign women, Walter shows us how they lived. By turns adventurous, demeaning, affectionate and disgusting, My Secret Life describes rich and poor, servants and employers, business transactions and passionate affairs. There are women who take lovers for pleasure, for financial security, for those little extras. Yellow-haired Kitty insists she is not a loose woman, but does it for “sausage-rolls, meat-pies and pastries.”

Sex isn’t a crime, though. Why write about this in Red Herrings?

Of Walter’s myriad encounters, some are pornographic and perverse. Some are sordid, but revealing. Many would today see him under investigation from Operation Yewtree.

He tells of backstreet rendezvous and opulent bordellos. He shows us teenage voyeurism and middle-aged affairs. He tells how young gents were introduced to sexuality by aunts, cousins, cooks or maids. The table of contents makes eye-opening reading:

An erotic nursemaid – Ladies abed – My cock – A frisky governess – Cousin Fred – Thoughts on pudenda… Baudy pictures … My aunt’s backside – Haymaking frolics…

Actual crimes do crop up. In volume 3, Walter is ‘bilked’. He describes the swindle luridly: a woman ‘bought’ for ten shillings suddenly demands £5. She calls for the ‘bully’. Frightened, Walter smashes a window to cry for help. A policeman walks away, bribed. He threatens his way out, chastened, clutching a poker.

Walter commits dreadful acts. He cajoles, coerces, and pounces. He never accepts that “no means no”: “Not one virtuous woman in a hundred would tell anyone…if a man said to her. ‘Oh! I’m dying to fuck you,’ and she’d feel in her heart complimented by his desires.”

Some lament their ruination. Others strike up long affairs with him. Walter feels little compunction.

Several of these episodes we would today describe as rape. He does not hesitate to pick up a girl as young as fourteen. The official age of consent was still 12. That this was already contentious is clear from her friend’s behaviour and a cab driver’s insults.

Walter thinks nothing of voyeurism in brothels, continental bordellos and railway toilets. He gets moved on for public indecency. He asks many women how they came to such a life, wilfully, coerced or by chance. He persuades a French prostitute to bring her sister to London: trafficking, of a sort.

Do an author’s crimes mean we should not read their work? Discuss. The most gripping account of a crime I’ve read was ‘Autobiography of a Murderer: Blind Rage’ by Henry John Reid, Granta 46, Crime, 1994.

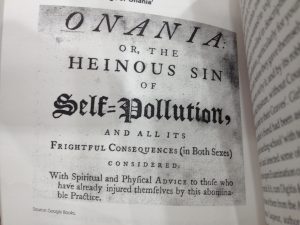

Yet even Walter’s identity is a mystery: most likely notorious erotobibliomaniac, Herbert Ashbee. This puzzle is fascinating. The Obscene Publications Act of 1857 coincides with the British Museum Library starting its Private Case. Thousands of volumes were excluded from the catalogue until the 1990s, locked in the stacks, accessible only to knowing scholars. Ashbee may have bribed the Museum to assure his collection’s safety in exchange for his Don Quixote first editions. Amid such censoriousness, it is no wonder Walter agonised whether to burn his manuscript or publish.

Whether fantasy or reportage, we can never know. It feels too particular, poignant, and tawdry to be invented. Walter does not aim to shock, like de Sade, manufacturing neither erotica’s happy endings nor pornography’s crescendos of perversity. Though at times ashamed or frustrated, he neither aggrandises nor justifies himself. This is a plain-speaking portrait of a sex addict.

Historical sources sometimes reassure us: we have thrown off hypocrisy; we’re enlightened. Yet, as Walter notes, “crying out at the sins of others was always a way of hiding one’s own iniquity”. Books may also warn how little we’ve improved. Walter’s entitled licentiousness is based on inequality sexual and financial, redolent of the era. Does this inequality just belong to the past?

It’s only twenty years since Edward Heath’s Chief Whip boasted of covering up ‘scandals involving small boys’. Amid continuing revelations of grooming, coercion, exploitation, institutionalised abuse, police collusion, and Operation Yewtree, Walter’s memoir reads not only as an unparalleled source but a challenge.

My Secret Life can be downloaded free at gutenberg.org or horntip.com.

Musician Dominic Crawford is creating an audio version at mysecretlife.org, with illustrations.

Abridged versions give sufficient flavour, if Walter’s thousand pages seem daunting.

William Sutton’s Lawless & the Flowers of Sin is published by Titan Books.

Please Feel Free to Share: