WHEN THE SIDEKICK HAS YOUR BACK

By Francine Mathews

By Francine MathewsOne hundred and one years ago this week, Edith Cavell--a British nurse in German-occupied Belgium in the first World War--was executed by firing squad. It was the Germans who killed her, allegedly for treason, although that seems an odd word to choose for aiding and abetting her own country. Edith was fifty years old when she died, and is famous for her final statement to the Anglican confessor who visited her a few hours before she faced death: "Patriotism is not enough." She had helped two hundred soldiers escape across the Belgian border to eventual safety in England, she is credited with saving civilian refugees as well, and last year the former head of MI5, Stella Rimington, revealed that she had found documents in Belgian archives that suggest Edith Cavell was a witting spy for Britain's nascent intelligence service. German occupiers were probably justified in shutting her down. But Allied observers were horrified that anyone would execute a noncombatant woman--and a nurse.

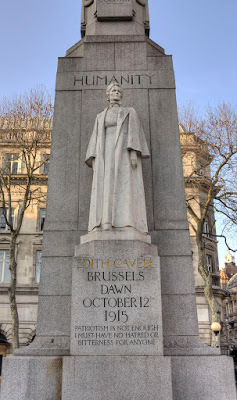

Edith Cavell Monument, London

Edith Cavell Monument, LondonEdith was lionized back in England, where her victimhood was swiftly employed in lurid propaganda posters and official postage stamps. Her statue stands in St. Martin's Place, near Trafalgar Square, and one of her dogs--Jack, the shepherd mix at the right of the picture above--was stuffed and placed on display at the Imperial War Museum. Apparently, he suffered this indignity for having survived Edith and the rest of the war.

But I confess that's not why I was riveted by Edith's picture in the New York Times. I noticed it immediately because of the other dog, the one that didn't survive her, the dog at her left.

The Airedale Terrier.

He's a terrier mix, it's true, and less than recognizable to those who love the breed today, but a hundred and one years ago Airedales were still evolving to their present state of perfection. And they were all over the Western Front, serving alongside the Allies as sentries, scouts, messenger-bearers and Red Cross rescue dogs. Some of them were discovered at the Battersea Dogs Home in London, others were donated by their owners, but most were trained by Colonel Edwin Richardson, who lived and worked in Carnoustie, Scotland. He was charged with preparing dogs for military field work at the Front, and quickly realized, he said, that the Airedale Terrier was by far the most able breed he could train, because--to paraphrase Col. Richardson--they cannot be dissuaded. They cannot be stopped. They are a force of nature that when deployed, turns out to be a powerful weapon. The Airedale Terrier became the Official Breed of the British Army.

Colonel Edwin Richardson and his Airedales-in-training

Colonel Edwin Richardson and his Airedales-in-training

Richardson put his canines through a six-week course of operations before dispatching them to the Front. Terriers are bred to hunt rodents by following them into burrows; like most terriers, Airedales love tunnels, culverts, drains--and trenches. They were perfectly comfortable finding their way through mazes of trenches criss-crossing the frontlines of France, and once accustomed to gas masks, could navigate with less danger. Many of them carried small first-aid kits strapped to their necks and were trained to find the wounded after battle. Others delivered communications tied to their collars.

Richardson put his canines through a six-week course of operations before dispatching them to the Front. Terriers are bred to hunt rodents by following them into burrows; like most terriers, Airedales love tunnels, culverts, drains--and trenches. They were perfectly comfortable finding their way through mazes of trenches criss-crossing the frontlines of France, and once accustomed to gas masks, could navigate with less danger. Many of them carried small first-aid kits strapped to their necks and were trained to find the wounded after battle. Others delivered communications tied to their collars.

By the end of the war, the BBC estimates that twenty thousand dogs were serving at the Front. During the 2014 First World War Centenary, as it was called in the UK, Airedales were honored with poppy-decorated neckerchiefs that read: We Also Served.

And why, you ask, do we care?

One hundred and one years ago, in that first year of world war, my father was born in western Pennsylvania. I never knew his parents--they died before I was born. It was only as an adult--raising my first Airedale puppy--that I learned something about my grandfather.

I was visiting my father's younger sister, whom I had never known well. She was elderly and infirm. But when she answered her front door, I was surprised to see an Airedale by her side. The breed is not that common, particularly in Colorado where we both lived. I'd had to travel to Utah for my first puppy, and I did so because for much of my life I'd yearned for just this breed of dog. I couldn't explain why--it had something to do with their jauntiness, their independence, their intelligence, their noble profiles. When I exclaimed to Aunt Peg at the coincidence of us both having Airedales, she looked at me quizzically and said, "Well you know--your grandfather bred them...."

Nessa and me, one Christmas

Nessa and me, one ChristmasNo, I hadn't known. And I shivered at her words. Ever since, I have been convinced that the bond between dog and human can come down through the generations. Airedales are in my blood. I've shared my life successively with five, at this point, each of them stretched luxuriously at my feet while I have typed away at novels. They are my Official Companions of the Writing Room.

So tell me, Readers: What breed can't YOU live without? Which dog will always have your back? Share your thoughts--and your pictures--with us.

Cheers,

Francine

Published on October 13, 2016 20:30

No comments have been added yet.