How to Read a Boring Textbook (Letters to a Young Pastor)

Dear ______:

Dear ______:

I have to say I’m kind of envious of envious of you. It’s officially fall. We finally have some cooler temperatures. But in college or graduate school late September is full of gifts.

You are partway into a new semester, walking with newly familiar books in your backpack across campus toward the library, under the blazing yellows reds and oranges of the leaves. It is one of the magical times.

But, once you get to the library you have to read those books. And you are quite right when you say that my most recent letter helped only with a few of your assigned readings. (I put primary sources first because they’re the most fun, and the most important.)

The Problem of Textbooks

Your backpack is burdened with fat hardbacks with glossy pages, written by reasonably famous professors. These are the books that give you the grand sweep of each subject. We call them “textbooks.”

We also, usually, call them boring — boring as hell, to be theologically precise. (Can you imagine a worse eternity than reading an endless stream of introductory textbooks?)

Trouble is, you need what’s inside those hardcovers, and you know you need it.

That’s where you’ll find a lot of the stuff that comes up on the midterm and final exams. Lectures will highlight material to help you come to grips with the whole subject matter in those books. On your own.

Map vs GPS

You want to get the best of the book in the least amount of time. I have a plan for you.

It is like when you want to find your way in an unfamiliar city. You want a GPS. You need a map.

That may seem old-fashioned. When I moved to Pittsburgh, I went into a drugstore and asked the clerk for a map. Now admittedly, he was maybe 17 years old, but he looked at me quizzically and said

A map? I didn’t know people still used those.

He had to ask the manager.

Anyway you need a map, even if you have a GPS on your phone. The map shows you what the land looks like, the big picture, so the turn by turn instructions of the GPS will make sense.

Understand the map and you can zip through the turn-by-turn with ease.

How to Read a Boring Textbook

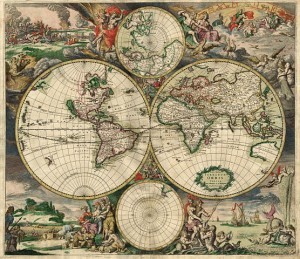

The problem with text books is that you have to make your own map. Think of yourself like like the early explorers: they knew where most of the continents were but they weren’t quite sure about all the coastlines.

So here is my five step map-making process.

1. Figure out what you should be looking for.

Look at the syllabus, and the title of the assigned chapter, and figure out what the topic is for the week.

Pause for a moment and ask yourself what questions this information leads to. What kinds of things are you likely to need to know?

This is like looking up the address before you start the car. You gotta know where you are going.

2. Find all the BIGGEST section headings.

Major section headings might be in all capital letters on a separate line, or all boldface, or both. These tell you how the author organized the whole shebang.

Different eras of a story?

Various theories on a problem?

Several concepts that make up an issue?

Map it: Take a sheet of paper and write out those big section headings proportionally. That is, if there are three big sections put one heading at the top of the page, one a third of the way down, and one two thirds of the way down.

That leaves you lots of room for notes as you create a one page summary map of the chapter.

3. Look to see what the subheadings look like.

Subheadings might be regular type or underlined on a separate line. These are the pieces of the puzzle, people making up stories, components making up a theory, or whatever.

Map it: Go back to your note sheet and put in the subheadings in their appropriate spaces.

4. Look to see if there are sub-subheadings.

Sub-subheadings might be bold letters in the first line of a paragraph or something else to indicate small parts making a whole. These are the smaller units, whether they are people or events or cases or whatever, that make up the major pieces of the puzzle.

Depending on the field you might find primary source evidence, data tables, important battles — it all depends on how the author organized the subject at hand.

Maybe map it: You might want to make a quick note about some of this, but mostly you just want to be aware of it in your mental map.

5. Read, and Fill in the map.

Read, and map the details: Now that you have a map to show what the territory looks like, it’s time to start the journey. Read the first subsection, and write a few brief notes on your sheet about its most important points. Keep doing this, section by section, to the end of the chapter.

A Tool to Keep at Hand

Now you have a useful roadmap to this week’s reading. You could probably make some spare change selling copies to your colleagues. Or you could just bring it to class, and study it before the midterm.

Happy reading!

Gary

————

If you enjoyed the post I hope you’ll share it — especially if you know any students!

The post How to Read a Boring Textbook (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.