The Unsung Hero of Slots

After a gestation period that lasted nearly a year, my latest Wired story is finally out. It's a tough one to summarize, but the tale centers on a Cuban-Latvian engineer who figured out a way to replicate the slot machines manufactured by International Game Technology (IGT), the S&P 500 company that has long dominated the slots industry. I don't want to reveal too much about the plot beyond that, lest I ruin the reading experience for y'all. Please, check it our for yourself and, should it give you some small dose of pleasure, help spread the good word.

After a gestation period that lasted nearly a year, my latest Wired story is finally out. It's a tough one to summarize, but the tale centers on a Cuban-Latvian engineer who figured out a way to replicate the slot machines manufactured by International Game Technology (IGT), the S&P 500 company that has long dominated the slots industry. I don't want to reveal too much about the plot beyond that, lest I ruin the reading experience for y'all. Please, check it our for yourself and, should it give you some small dose of pleasure, help spread the good word.

But I'm happy to offer some extras throughout the week, as is my wont when major projects drop. The detail I've been dying to share with y'all is the one about the invention that has come to define modern slot machines, a patent that vastly improved casino revenues by convincing players that their eyes could allow them to accurately assess a machine's odds. As I explain in the story:

Slots didn't truly become America's favorite casino pastime until a Norwegian mathematician named Inge Telnaes came up with the most brilliant gambling innovation since the point spread.

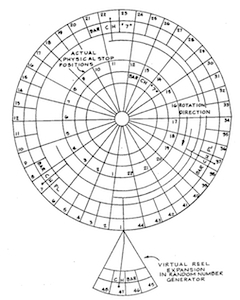

The problem with slot machines, as Telnaes saw it, was that their jackpots were limited by the number of reels they could use. Since players expected each reel to have no more than 10 to 15 symbols, a machine needed many reels to make the odds long enough to justify a huge payout when all the cherries or bells settled into a row. But the more reels a machine had, the more players were reminded of the fact that their quest for riches would likely end in futility; no one wanted to try their luck on a machine with dozens of reels (or, alternatively, hundreds and hundreds of symbols on enormous reels).

Telnaes' solution to this conundrum was US Patent Number 4,448,419, awarded in 1984. His invention called for slot machine results to be determined not by the spinning of reels but by a random-number generator. The reels on such a machine would display only a visual representation of the generator's results, lining up when a winning number spit forth or (far more frequently) settling into a losing mishmash of symbols. The patent made possible the development of slot machines that could offer extremely long odds—and thus enticingly massive jackpots—while still appearing to have just a few tumblers.

The fact that random number generators power all modern slots suggests that any money spent on tip books is money completely wasted. Yet there is no shortage of media that promises to teach paying customers how to beat those dastardly one-armed bandits. In the end, of course, playing slots requires no more skill than playing Candy Land. Less, even: you have to count the spaces in Candy Land.

Please, read on, and I'll have more story extras as the week progresses.