Carpe Noctem Book Interview With Brynne Rebele-Henry

THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

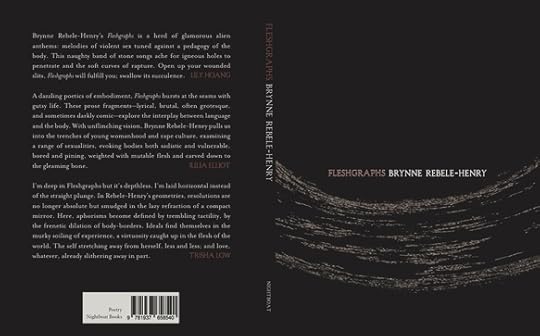

I chose the title Fleshgraphs because the book is a literal graph of flesh. The book is composed of confessions (inspired by both religious confessionals and online confessions), and is about benign or intense or horrible things happening to bodies, and each experience is told through a different numbered fragment. The book is also composed of fragmented short paragraphs, or graphs.

For the book’s cover, I knew I wanted there to be a graph or web of some sort, and that I wanted it to be black, red, and off-white. The amazing people at Nightboat sent me several covers to choose from, all graphed (my second favorite one was composed out of a print of the veins of a leaf!)

The three words I’d use to describe my book are: bodily, gurlesque, and grit. I wrote the book as a kind of shrine to the obscene: an internet Mütter Museum-like collection of flesh-secrets and confessions, a burlesque of sexuality and anti-sexuality, and the body.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

I was trying to write a feminist dissection of rape culture and online confessions, but also a celebration of the body’s resilience.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I wrote Fleshgraphs in a few weeks when I was fourteen. I wrote most of it late at night at my desk.

For revisions, I’ve always liked getting physical with the work: I’m a visual artist as well, and I think that that process corresponds to my revision process. I usually print out the work and then highlight or color certain pages, phrases, or passages. Each color has a different code. Sometimes I cut parts of the pages out and then combine them with other pages. I usually do this to a manuscript about four times before I make the changes digitally. I keep the old versions of all of my manuscripts in binders in case I ever want to go back on some changes. I have about ten different versions of the same novel in a storage box that I keep in my writing desk.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

For this book, I wrote most of the fragments as a kind of Jenga puzzle, each section fits into the other. During the editorial process with Kazim, I wrote more into the ending, cut some fragments, and moved other fragments around.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I like to try to craft strange body worlds with my poems, to make them kind of like a bizarre grotesque-burlesque show. I like to take language used against women or queer people and then juxtapose it in a way that takes away the demeaning usage of it. I love reading poems that break you but make you want to read them again.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

1.

I alphabetize the girls by tens and letters. First: Annie and her cellulite thighs that made her say of herself: walrus. I would bite them with my too sharp incisors. Second: Betty and the weird sounds she made that were more like birth than sex and her pinup rolled back hair. Third: Carrie, and her light moustache. Fourth: Diana and her autumn mouth and how she always burned cookies. I stop at six because that’s too fucking sad but I think of her knuckles and the sound they made against my forehead still.

2.

The birth was a slick of fluids I never knew existed, the color spectrum on a palette of torn labia and mewls. My baby’s face looks like a burned cat and I don’t want to name this cartilage watermelon, this alien kitten. Instead I let it bite my torn nipples and sing lullabies in the language of my mother that I never bothered to know.

3.

Marco says, you like the girls, fucking them, I mean? I think, have you seen my haircut? And the way I know how to walk in strip clubs, how I know to hold my over-priced beer?

4.

Every time I sleep I dream of an abscess, usually on the side of my face. I squeeze and an explosion of pus, a tidal in my fingers and I don’t like bandaids.

5. I put on my wife’s lipstick.

These were the first Fleshgraphs pieces I wrote—before it became a book, I initially thought it was going to turn into a hybrid poem.

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

“Please read this. It’s about confessions, sex, bodies, and secrets.”

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

For me, being a poet is a political act. I was talking to my father about this a little while ago, and he said something along the lines of: being a poet is automatically political because the work doesn’t adhere to the conventions of language. You can have a poem composed out of air, or rocks, or written in dirt, or a poem composed of the same word a thousand times. It’s harder to be that free with prose (I know, because I write in all genres). As for what gives me the most pleasure: when my writing effects or changes someone. I’ve had people message me about being inspired to come out or start writing or publish gay work because of my poems, and it makes me cry every time. I’m not sure what truly scares me, I haven’t figured it out yet. For a while I was really afraid of writing autobiographical or more personal pieces, but I just wrote a book-length essay written in the forms of poems about fertility runes and girlhood and discrimination, so now I’m no longer afraid of writing personal pieces.

I’ve heard poets say that they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you?

I write mainly about bodies and lost people, but other than that my stories change with each piece.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

It tries to! I’m a lesbian, and almost all of my work addresses violence against women/queer women/queer people’s bodies, queer sex and sexualities. I write literary fiction and YA too, and in my fiction I try to normalize queerness (in most mainstream novels, queer people never appear except as tokens, or tropes). So because of that I make all of my characters LGBTQ+. And I try to write about the histories of violence and persecution and anger towards women and femmes/fems, and queer female sexuality. I think all art is political, even work that doesn’t seem overtly so, because the act of creating something is innately political.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I like old medical textbooks, especially ones pertaining to physical anomalies or geography, or old psychological texts or reports.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on the first draft of a collection of political and personal essays and a lesbian comedy screenplay pilot!

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

The Red Parts: Autobiography of a Trial, by Maggie Nelson.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Danez Smith, Ocean Vuong, Anne Carson, Aidan Forster, and Tarfia Faizullah.

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

“What do you most want to write?”

And the answer to that would be a novel about Catherine of Siena, her queerness and her sainthood, how she obtained the title of a saint through starvation and flagellation, and the correspondences between godliness and masochism in medieval Christianity.

***

Purchase Fleshgraphs.

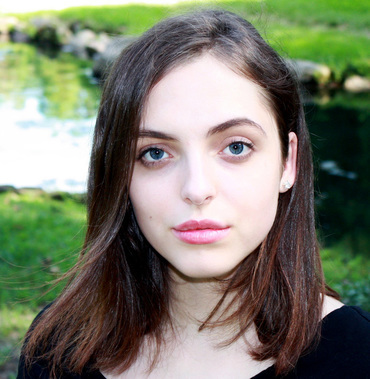

Brynne Rebele-Henry’s poetry, fiction, and nonfiction have been published in Denver Quarterly, Prairie Schooner, Fiction International, Rookie, and So to Speak, and she was the recipient of the 2016 Adroit Prize for Prose for an excerpt from her novel. Her first book, Fleshgraphs, is forthcoming with Nightboat Books in September 2016. Find her online at Brynnerebelehenry.com.

Brynne Rebele-Henry’s poetry, fiction, and nonfiction have been published in Denver Quarterly, Prairie Schooner, Fiction International, Rookie, and So to Speak, and she was the recipient of the 2016 Adroit Prize for Prose for an excerpt from her novel. Her first book, Fleshgraphs, is forthcoming with Nightboat Books in September 2016. Find her online at Brynnerebelehenry.com.

Published on September 01, 2016 15:21

No comments have been added yet.