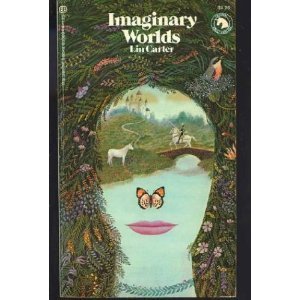

Review: Imaginary Worlds (Lin Carter, 1973)

The publishing world moves. Let's crank some steampunk into this metaphor-- think of it as a huge shuddering jury-rigged monstrosity fussing and clanking along an unlit track in a clockwork universe. The location of the control room is unknown, the identity of the pilots a subject of universal debate. Bits and pieces of the leviathan are always going dark, and repair crews are forever scuttling about, never armed with ideal tools or knowledge for their jobs, trying to coax them back to life. Large sections of the leviathan occasionally shear off and plunge into the darkness. Energetic and desperate smart-asses are always building weird new edifices on top of the existing mega-structure. Sometimes these additions blaze into glorious life. Sometimes they explode.

And yet the whole kit-bashed triple-bypassed juggernaut moves ceaselessly forward. It doesn't slow down, it doesn't stop, and it certainly doesn't go back to revisit old points along the track.

Lin Carter's Imaginary Worlds is an artifact from another time, forty years ago, when fantasy was just starting to come into what you might call the relatively unified commercial identity we take for granted now. It's an overview of fantasy written after The Lord of the Rings broke into broad awareness, but long before terms like "epic fantasy," "fat fantasy," and "extruded fantasy product" were anything but a glimmer in the minds of internet complainers. The World Fantasy Awards didn't exist. Tolkien imitators were not yet a sub-industry. Roleplaying games were still specks in a corner of the geek petri dish. Books that self-identified as science fiction were the Big Dogs, and commercial fantasy was a puppy still trying to figure out how its eyes and legs worked.

Forty years farther along the track, some of us riding the leviathan could do with a glance back to put things in context. Despite wince-inducing weaknesses, Imaginary Worlds does passable service in providing that glance.

An examination of the titles in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series of 1969-74 (of which Imaginary Worlds was the sole non-fiction entrant) shows quite a few works originally published in the 1920s, 1930s, and even some as far back as the mid-19th century. The series included orientalist romances, philosophical analogies, "weird tales" and extracosmic horror, sword-and-sorcery and planetary romance, and even prose retellings of traditional legends. This is the melange that Carter's book attempts to cover, describing emerging movements and traditions but not neglecting idiosyncratic and sometimes unilateral experiments.

The book is brisk and information-dense. Names, titles, and reading suggestions are thick on the pages. This can truly be called an inclusive survey of Western fantasy up to 1973, but the emphasis is resolutely Western. Asian literature and legend, for example, are mentioned only in the form of Western pastiches. If Carter did any research on contemporary fantasy anywhere except Europe and the Anglophone nations, it was glaringly omitted from Imaginary Worlds.

Carter also has no shortage of admirable enthusiasm for the work of female writers, but his quaintly gallant chauvinism is comical, even as an artifact of its time. Katherine Kurtz is described as a "vivacious blonde." At one point Carter feels it necessary to defend L. Sprague de Camp's "red-bloodedness" with a reference to "his petite blonde wife.*" Alexi Panshin is granted a description as "writer and critic" but his wife and full collaborator Cory is only "his attractive wife." Ursula LeGuin and Evangeline Walton, though lavished with praise for their work, are never given any physical description. I don't think it's uncharitable to suggest it has something to do with the fact that they were over 40 when Imaginary Worlds was written.

Carter's prose can be problematic. On the positive side, his voice is strongly developed and flavorful, projecting amiability and a passionate love for his subject. On the other hand, he seems to have never met a hyperbolic adverb he didn't like. Nothing can be merely "successful" in his descriptions; it must be amazingly successful, surprisingly successful, stupendously successful! This love of hyperbole and "embiggening" is carried into everything, even biographical details, giving rise to the uncomfortable sensation that Carter is sometimes inflating legends rather than reporting facts.

His unexamined self-satisfaction is evident in his "how to write fantasy" chapters as well. He offers a great deal of genuinely useful suggestion and criticism, but there is something giggle-worthy in seeing Carter tsk-tsk other writers for their unpoetic invented names before proudly citing his own "Thongor the barbarian" as a shining example of how to do it right.

With those major caveats registered, Imaginary Worlds is still a useful and acceptably detailed introduction to quite a few authors and once-popular (or at least more common) styles of fantasy that have fallen into shadow over the years.

*****

* The full reference, "his petite blonde wife and his two strapping sons," is even more eyebrow-raising. Nowhere else in the book does Carter feel the need to single out another male author and reassure the reader that the guy's dick works.

Published on July 17, 2011 11:37

No comments have been added yet.