On Writing Genre Characters

Somewhere in the early aughts, everyone started talking about how their story is “really about the character.” It become most pervasive in genre fiction—be it TV, comics, novels, whatever—where accentuating the human story—i.e. stressing that the story is really about the struggles of the people involved—made the higher concepts more palatable to mainstream audiences. Which, ultimately, is great—it doesn't take too hard of a look to realize that works of genre—sci-fi and horror especially—have erupted across the mainstream. From Walking Dead to Star Wars to Man in the High Castle and everything in-between (including DC and Marvel's television/film efforts), genre fiction is everywhere. And, still, when we talk about genre fiction—and, on my side of the table, when you try to pitch genre fiction—the crux of what makes the story work relies, heavily, on character. But, somewhere along the way, the role of character within the context of genre has lost its focus—what makes characters so rich and compelling in genre fiction, tackling big, high-concept ideas and themes, has taken a backseat to the mundane/ordinary, and the latter is not a formula for the best genre fiction or the best character work.

Let me explain.

To me, this reliance on character as a way to translate genre fiction to contemporary mainstream audiences has its roots in the show Lost. Just to disclose myself: I adore Lost. It's one of my favorite TV shows of all time. Despite its underwhelming ending, it took me on an amazing journey for five solid seasons—it had adventure, heart, big ideas, incredible performance, smart philosophies, wicked time travel, and it did, on the whole, some pretty amazing things, especially when you consider it was on network television. Lost, though, represents the first big breakthrough of genre fiction into the mainstream, beating Battlestar Galactica by a narrow margin. And what people gravitated towards—amidst the time travel, mysterious hippy cults, polar bears, crazy mysteries, etc—were the characters. The cast of castaways, without question, helped that show break through the glass ceiling of genre fiction. They were deeply human with real problems; when they connected it felt very honest; when they failed, it was heartbreaking. I'll always remember so many character moment, like Locke—the grittily determined John Locke—screaming from his wheelchair “Don't tell me what I can't do!” as he was denied participation in an Australian walkabout. It was a revelatory moment that was as equally shocking as it was resounding. Lost, especially those early seasons—delivered countless moments just like this.

But, here's the thing—as good as Lost's characters were, what made them truly memorable is the context they were placed in. And I don't mean the plot, necessarily. What I mean is that, at its core, Lost was telling a profound story of spirituality. The wrestling of the corporeal world (science) with the spiritual world (religion, faith) made for a thematic playground that gave the story depth, soul, and rich uniqueness that helped make Lost the wild success it became.

That, at their core, was what the characters were wrestling with—the redemption of their souls. Lost was never just about a group of castaways dealing with being trapped on a weird island. Right there is the biggest, most important distinction that helps make Lost as special as it is. And that, to me, is where other works of genre fiction falter—they fail to plume that extra depth and make the story about something more.

Making genre fiction and saying “but it's really about the characters” isn't enough. If the story is about an alien invasion, and the character arcs are them dealing with the alien invasion, something is missing. What about the alien invasion makes these specific characters so unique—why is their story in this context worth telling? Most times, what we end up seeing is characters falling back on the mundane. One of the characters is dealing with the recent loss of his/her spouse; another character is a dealing with being an alcoholic. These are fine character routes to take, don't get me wrong, but they need a richer context. Again, going back to Lost—sure, the character arcs weren't completely original all the time. But whatever they were dealing--their ordinary struggles--were propped up on the richer context of this spiritual journey they were placed on, whether they liked it—and accepted it—or not. You need something deeper going on that heightens the characters' experiences in context of the story.

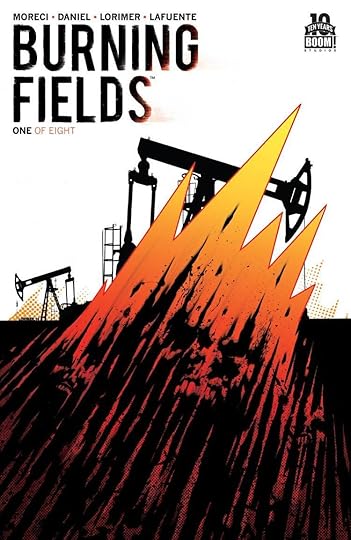

Admittedly, this is something I aim for in all of my work. Take for instance my Boom Studios! series Burning Fields (co-written by Tim Daniel, art by Colin Lorimer, colors by Joana LaFuente, letters by Jim Campbell). On the surface, Burning Fields is a procedural horror story about a monster that's possessed a cult of murderers to stoke the flames of contention in Iraq. A dishonorably discharged military investigator and an Iraqi detective team up to thwart this heart of darkness and defeat the terrifying monster. That, more or less, is the plot. But, underneath that is a story of faith, and redemption, in the face despair. Dana is someone who has lost her faith, lost her capacity to love herself, or others, because of what she's endured in her life; Aban, her partner, is a man who has maintained his faith because of his love and the things he endured in life. Their actions, and growth/transformation over the course of the story, is made richer, I think, because there's something deeper, very intentionally, going on beneath the surface. Hemingway once said the stories are life glaciers—10 percent above the surface, 90 percent below. I take that insight to heart.

Think, also, about one of the greatest periods in genre fiction—postwar noir in the United States. Believe me, I've seen enough of these films—everything from the staples of this period to the most obscure entires—and there's only a handful of plots utilized in countless noir movies. And that's fine—because, in the end, what makes these stories so special isn't necessarily what happens, it's what it all means.

What you have in these stories, at least in the best ones, is a unsettling look at the underbelly of postwar America. Underneath the veneer of victory over the Axis powers, financial boom, and the newfound suburban sheen, things were really fucked up. You had these desperate men and women aimlessly roaming the cities, their failures magnified by the shadow of national victory. In their failures, they scheme and they plot—they try to make that one big score, securing that jolt they need to get out of their miserable conditions. Of course, their ambitions are destined to fail, condemning them either to death or a further plunge into their existential nightmare of broken dreams and ruined hopes.

I can write about postwar noir for days, but the point is that the best of these films, and books, all had one thing in common. They shared this exploration of postwar bleakness, and this incisive look at the United States, its grimy cities and morally ambiguous characters make the stories all the more richer, compelling, and rewarding.

Another work of mine, Roche Limit, attempted something similar. Its premise was based on the wonder and excitement of space travel and exploration. But, underneath that, was a decaying core of empty promises, a ruined future, and existential crisis. Roche Limit is probably the most intimate alien invasion story I could concoct, and purposefully so. That intimacy helps drive home what was going on underneath, this examination of the human soul—its preservation, value, and how, even as we move into a brave new world of technology, space travel, and other forward-thinking innovations, the world that we must cradle, always, is our own. Our loves, our families, our passions--all the things that define our existence. Roche Limit is the story of a human colony gone terribly wrong—because of hubris, because of forces we can hardly understand or control. What it's about, though, is something much deeper, and because of that, to me, the characters are all the more complex and identifiable. Don't get me wrong--Roche Limit is a messy book, and I don't always hit the mark. But, although the undercurrent isn't always perfect, it does exist--that layer is there that takes it beyond the simple "it's an alien invasion story with characters dealing with an alien invasion."

Roche Limit: Monadic #1 coming March 16! The first volume of the final arc is upon us soon...

I've said this a thousand times, and I'll stick to it forever: If someone asks you what your story is about and you describe what happens, you haven't answered the question. What your story is about—the theme, the plot, what you're trying to say, that richer thing that's underneath the surface, driving the plot and characters—is not the same thing as what happens. There's theme, and there's plot. They are not interchangeable. And just because you have a high concept doesn't mean that the characters can be any less than high concept themselves; they have to be on equal footing and all be connected--story, character, theme.

Point being, genre fiction lets you explore fantastic worlds, big ideas, and show us things we can only begin to imagine. But, ultimately, to make the story reach that next level is the marriage of character and plot with theme enriching them both. Tie it all together, have them work in concert, and you'll have something outstanding.

Okay, that's my two cents. Like what you've read here? Subscribe! There's a little box on the upper right over there--just add your email. No spam, no bullshit. Just updates every now and then. And you can always visit my shop--I just quit my day job so--time to sell my inventory!

Thanks for reading--good luck out there in the writing world!