Tracing The Trails Of Richard Bachman : Rage

I don’t care who you are.

don’t care who you are.

I don’t care how successful you are or how famous or how much love and adoration you have received. Anyone who engages in artistic endeavors on a regular basis faces a daily siege on all fronts against the bulwark of their self-esteem and self-confidence. Putting yourself out there in the world, so exposed and vulnerable leaves you open to any number of attacks from those who might cruise past your work. All you can do is hold it up there and hope people like it for what it is.

Furthermore, I would be willing to bet that if a person manages to achieve a certain level of fame, it could lead to a fair amount of self-doubt. If your talents started to slip or if you started rushing things or going about the wrong approach to a project, who would be there to tell you that your work isn’t up to standards? So often, when writers start to hear people tell them things like, “I love what you do” or “You have such a fresh voice”, you run the risk of starting to obsess over what it is they find so great. If you worry too much about reverse-engineering your own process you can end up breaking it.

To take that one step further, I can also see that if a writer were to achieve a level of mega-success, you could start having difficulty trusting that people are buying the books for the right reasons. Is it because they like the books? Are the stories really that good? Or is it because they saw the name of someone famous on the dust jacket so they bought the book because it must be good.

Personal note to universe? I would like to sign up for havig this problem. Thanks.

The point of this rambling introduction is that I can understand (in theory) what might have driven Stephen King to start publishing books under the name Richard Bachman. You want to believe that people come to your work out of love for the words, as opposed to love of your celebrity. After all, this would be a large reason why King’s oldest son would choose to publish under the name Joe Hill. So essentially, King began using the name because he wanted to see if he could still make it happen, using an unknown name with little or no effort to publicize it. In King’s own words from his introduction to The Bachman Books, “I think I did it to turn the heat down a little bit; to do something other than Stephen King”.

King had these books piled up, some of his earlier efforts, essentially burning a hole in his pocket and he wanted to publish them. The concern from his publisher was that the market would get over-saturated if the reading public were to see more than one Stephen King book in a year. This seems more far-fetched looking back now, especially considering the mid to late eighties when it wasn’t uncommon for King to publish two or three books in a year.

Things came to a head for Richard Bachman in 1985. According to King, he was receiving letters from day one asking him if he was Bachman. Still, it was in 1985 when the official outing took place, caused by several key clues. First was the fact that all of Bachman’s books were dedicated to people who also had connections with Stephen King. This was significant enough but the deal was sealed by a book clerk from Washington DC, Steve Brown. Brown had harbored suspicions about Bachman’s writing style for some time and finally took the time to go to the Library of Congress to look up the publisher’s information on the books. It was there that he discovered King listed as the author on record. When Brown contacted King’s representatives with this information, he was contacted directly by King who gave him his blessing to write an article and agreed to sit for an interview.

Thinner would be the last book published by Bachman before the unveiling although, interestingly enough, King had apparently intended for Misery to be a Bachman book. Once he was outed, these plans changed. There would be a few more Bachman books to come but for the time being, King actually announced to the public the news of Richard Bachman’s death.

Those who have read his book, The Dark Half will likely find the story of his unmasking familiar as it would become the inspiration for Thad Beaumont and George Stark. After King went public, the four books published under Bachman’s name previous to Thinner were bound into a single edition and published as The Bachman Books.

As my reviews of King’s books have now reached the point where this collection was originally released, I thought it would be a good time to step aside for a moment and review each of Bachman’s books as they were published.

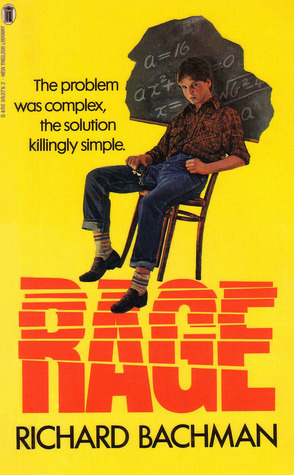

Rage was Richard Bachman’s first book, published in 1977. The story is of a disgruntled teenager who brings a gun to school and murders one of his teachers. Following the killing, he proceeds to hold his fellow classmates hostage while he toys with school and police authorities. He confronts his classmates, spurring and exploiting the conflicts between them as the social dynamics of the high school get mixed up in a sort of metaphorical crucible.

Rage bears a certain distinction from the other books of King’s catalog. While he is no stranger to the experience of libraries banning his books, Rage was the one title that he, himself chose to take out of circulation. In the nineties, there were a series of actual events involving school shootings and I have no doubt that at some point, King had to start to feel uncomfortable with the implications of life too closely imitating art. In one instance, a copy of The Bachman Books was actually found in the locker of a student responsible for killing a number of his classmates and King made the decision to pull the book. Rage was kept on the market for some time after as a part of The Bachman Books, but not as an individual title. To date, in the US, The Bachman Books collection has also been allowed to go out of print and is only available through third-party sellers. In 2007, King would release the final Richard Bachman book, Blaze, and in the preface said, regarding Rage, that it was “now out of print, and a good thing.”

I’m not really one to put much stock in the notion of popular art directly causing real life violence. One look on a global scale will show that in countries across the world, people are reading the same books, watching the same movies, listening to the same music and playing the same video games with barely a fraction of the rate of violent crime. Still, I can’t say that I hold it against King for feeling increasingly uncomfortable with the book being on the market in light of the events in the world at the time. To be sure, looking around in this country as it stands, nearly twenty years later, the book has actually become more culturally difficult to bear.

As for the story itself, I have to admit that I wasn’t as taken with Rage as some others have been. Part of me suspects that this book probably gains a special level of notoriety among King fans specifically because of the controversy around it as opposed to the merits of the book itself. Rage was one of King’s earlier efforts at novels and to be completely honest, I think his inexperience shows a little. The book isn’t bad. There are some powerful moments to be sure but as a whole, I kind of feel like the story tries too hard to be a sort of social exploration. Reading it, I couldn’t help thinking that the story was like some kind of bizarro version of The Breakfast Club, but where the principal was replaced by a combination of Holden Caufield and Travis Bickle. It was like King was making such a concerted effort to be earnest with the message of the story that I often had the feeling like I was reading a script for a student theater production or a one-act play.

It doesn’t help that for the most part, I found the protagonist of the story, Charlie Decker to be kind of an entitled shit. His backstory is given out in bits and pieces, but it is all from Charlie’s perspective so who knows how seriously we can take it. If the stories told are true, his father is clearly pretty unsuited as a parent but Charlie himself also behaves badly in many of these flashbacks as well.

The reactions of the other students in the story seemed a little far-fetched to me as well. They just seem to be a little too casual and comfortable in the way they react to a classmate barging into class and shooting their teacher, right in front of them. I know that the initial killing was important in order to create that moment of shock for the reader, but I actually think the story would have worked better if it had just been Charlie taking his class hostage, without the murder at the start.

In sum, not the greatest book I’ve read, but far from the worst. I obviously can’t say how I would have reacted to the book, not knowing who the author was. Since I was only nine when he was revealed, I have pretty much always been aware of the fact that Richard Bachman was Stephen King. I will be interested in seeing how the other books shake out from here.

I suppose the one piece of evidence that can be taken into consideration when summing up Richard Bachman’s legacy is this: in 1984, Thinner had sold around 28,000 copies after its initial publication. Upon discovery of the fact that it was actually a Stephen King book, sales went up to nearly 300,000 copies. Take that for what it’s worth, but I think it’s pretty safe to assume that the King name was the right way to go.

My name is Chad Clark, and I am proud to be a Constant Reader.