chatting with ghosts a visit to E.B. White’s farm

Have you ever wondered by what mysterious alchemy a whim becomes a wish, and a wish a reality?

Have you ever wondered by what mysterious alchemy a whim becomes a wish, and a wish a reality?

I’m pretty sure it requires some combination of love and pure intention to transform an idle fantasy into an actual event. Oftentimes, a spirit of adventure is necessary, too. Oh, and a willingness to envision – even if the vision itself seems far off and far-fetched.

This is a tale of a daydream that actually did come true, a road-trip story that had its beginnings in the pages of a cherished book and then slipped right out of fiction and into real life. Sometimes, the stars line up. Sometimes, all the puzzle pieces fall into place. And sometimes “real life” feels, if only for a day, graced by a touch of magic. Want to come along?

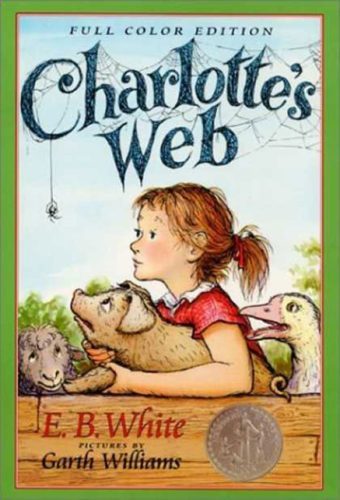

Because I became a surrogate mom to a daughter late in life (a tale with its own magic, which I tell here), the two of us had some catching up to do as we got to know each other. It didn’t surprise me, though, to learn that Lauren and I shared a love of E.B. White in general, and of Charlotte’s Web in particular. Having adored White’s enduring classic as a child, Lauren eagerly introduced her two young nieces to Fern and Wilbur and Charlotte as soon as they were old enough to listen. Having felt the same, I shared with her that I’d read Charlotte’s Web to my own boys, not just once but many times over the years, eventually relinquishing the final chapters first to Henry, and later to Jack, to read out loud, so they wouldn’t have to listen to me trying to speak through my tears.

Because I became a surrogate mom to a daughter late in life (a tale with its own magic, which I tell here), the two of us had some catching up to do as we got to know each other. It didn’t surprise me, though, to learn that Lauren and I shared a love of E.B. White in general, and of Charlotte’s Web in particular. Having adored White’s enduring classic as a child, Lauren eagerly introduced her two young nieces to Fern and Wilbur and Charlotte as soon as they were old enough to listen. Having felt the same, I shared with her that I’d read Charlotte’s Web to my own boys, not just once but many times over the years, eventually relinquishing the final chapters first to Henry, and later to Jack, to read out loud, so they wouldn’t have to listen to me trying to speak through my tears.

Charlotte’s Web may masquerade as a children’s book, but it is really one of the most profound and tender portraits of a friendship ever written – timeless, ageless, full of light and shadow, humor and deeply felt emotion, oddly endearing details and unforgettable characters, both human and animal.

It is also, for me, a touchstone, a reminder of what it is to write simply and well, to observe all beings with compassion, to honor life’s impermanence, its fleeting beauty, its enchanting and engrossing twists and turns. And, too, this cherished book is a reminder that love can become sadness, that even the most special friendships end, but that the pain of that loss is always worth enduring in exchange for the rare gift of being seen and known and cared about for a time.

So when Lauren wrote me last fall to ask if I’d be game for a trip to E.B. White’s saltwater farm in Brooklin, Maine, I didn’t hesitate before saying “yes” – a yes which set all manner of things in motion.

So when Lauren wrote me last fall to ask if I’d be game for a trip to E.B. White’s saltwater farm in Brooklin, Maine, I didn’t hesitate before saying “yes” – a yes which set all manner of things in motion.

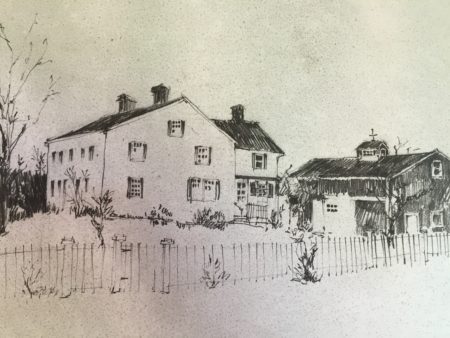

Lauren tracked down the current owners of the farm, Bob and Mary G., who purchased the property just after White’s death in 1985. White was a notoriously private man, and his former house has always been and still is a private home, not a tourist destination. And yet, this kind couple have inhabited their special place for over 35 summers, with a deep respect for its gentle ghosts and its singular history. Changing and updating only what needed to change, they have also lovingly preserved whatever could be saved, a way of honoring both E.B. and Katharine White and much of the character of their beloved homestead.

Fortunately, Bob and Mary also understand that for some of White’s most devoted readers, the hunger for pilgrimage runs deep. With quiet hospitality, they do their best to accommodate those who feel compelled to make the long journey to Brooklin, if only to breathe in the salt air and to see for ourselves the venerable old barn that inspired the book we hold most dear in our hearts.

Over the course of many months, Lauren initiated a correspondence with Mary, arrived at a suitable summer date for the two of us to visit, found us rooms at an Airbnb down the road, and bought herself a plane ticket north. And so it was that the long-awaited day arrived at last. We set out early in the morning from my house in New Hampshire, carrying clothes for all weather, coolers packed with food, provisions for the road, walking shoes and some art supplies.

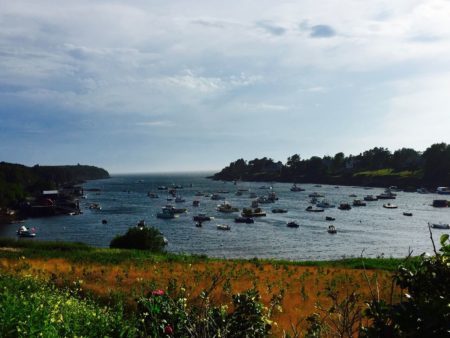

First stop: my parents’ house on Bailey Island. For a girl born and bred in Connecticut and transplanted south to Atlanta right after college, a first trip to the coast of Maine was pretty exciting in itself. And I loved seeing this old family place I know and love through the delighted eyes of a newcomer. As the mother of sons, it’s quite a treat for me to have the company of a daughter, especially a young woman who appreciates my motherly ways and my skills with a lobster cracker.

First stop: my parents’ house on Bailey Island. For a girl born and bred in Connecticut and transplanted south to Atlanta right after college, a first trip to the coast of Maine was pretty exciting in itself. And I loved seeing this old family place I know and love through the delighted eyes of a newcomer. As the mother of sons, it’s quite a treat for me to have the company of a daughter, especially a young woman who appreciates my motherly ways and my skills with a lobster cracker.

We unpacked the car and struck out on foot, soaking up the sun and working up an appetite for dinner – lobster salad and champagne, to celebrate our togetherness, the beginning of our adventure, and the singular beauty of a July afternoon in Maine. The sunset that first night was perfect. We sat at the table for hours, talking, watching day turn to night, marveling at the fact that we, who had found each other through, as Lauren says, “the power of the pen,” were finally here, doing this thing we’d each dreamed about almost forever.

We unpacked the car and struck out on foot, soaking up the sun and working up an appetite for dinner – lobster salad and champagne, to celebrate our togetherness, the beginning of our adventure, and the singular beauty of a July afternoon in Maine. The sunset that first night was perfect. We sat at the table for hours, talking, watching day turn to night, marveling at the fact that we, who had found each other through, as Lauren says, “the power of the pen,” were finally here, doing this thing we’d each dreamed about almost forever.

Early the next morning we were on our way further downeast, which is to say north on Route 1, the very route E.B. White himself used to travel from his desk at the New Yorker to his beloved rural retreat. Seeing the landscape unfurl before us — the fields rolling down to the sea, the old white farmhouses hunkered down into the earth, the yards bedecked by country-fair-worthy zinnias and bright flags of drying laundry flapping in the wind — I could fully identify with White’s irrepressible desire to flee their hot, dry rented rooms on the Upper East Side and relocate to the rambling old house with a barn attached that he and his wife Katharine had bought in Maine. It was 1938 when they left New York, a move EBW himself considered “impulsive and irresponsible.” He and Katharine had enviable jobs at the country’s most esteemed magazine and, as White acknowledged “everything was going our way.”

Early the next morning we were on our way further downeast, which is to say north on Route 1, the very route E.B. White himself used to travel from his desk at the New Yorker to his beloved rural retreat. Seeing the landscape unfurl before us — the fields rolling down to the sea, the old white farmhouses hunkered down into the earth, the yards bedecked by country-fair-worthy zinnias and bright flags of drying laundry flapping in the wind — I could fully identify with White’s irrepressible desire to flee their hot, dry rented rooms on the Upper East Side and relocate to the rambling old house with a barn attached that he and his wife Katharine had bought in Maine. It was 1938 when they left New York, a move EBW himself considered “impulsive and irresponsible.” He and Katharine had enviable jobs at the country’s most esteemed magazine and, as White acknowledged “everything was going our way.”

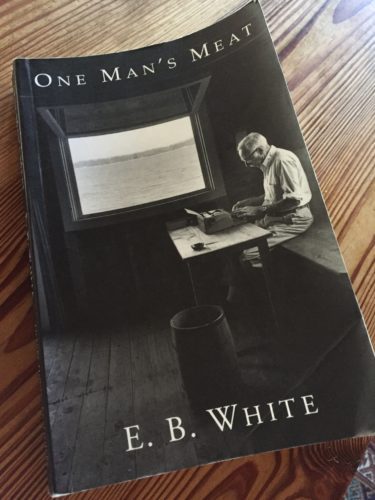

Even so, as he recalls in his introduction to One Man’s Meat, the essays he wrote from Maine for Harper’s, “I led my little family out of the city like a daft piper.”

A friend, upon hearing EBW was departing the city for country life, said, “I trust that you will spare the reading public your little adventures in contentment.” Fortunately, White paid little heed to that advice. (Years later, however, he admitted he still heard the man’s leering voice in his mind every time he sat down to write about “any delights that I experience.”)

Of course, he had no way of knowing his greatest work lay ahead of him, or that it would be inspired by the farm, by his deepening love of nature, by his endless curiosity about spiders and rats and geese and pigs, and most of all by his insatiable pleasure in the world. But as an old man looking back and writing a new introduction to One Man’s Meat, he had this to say:

Once in everyone’s life there is apt to be a period when he is fully awake, instead of half asleep. I think of those years in Maine as the time when this happened to me. Confronted by new challenges, surrounded by new acquaintances – including the characters in the barnyard, who were later to appear in Charlotte’s Web – I was suddenly seeing, feeling, and listening as a child sees, feels, and listens. It was one of those rare interludes that can never be repeated, a time of enchantment. I am fortunate indeed to have had the chance to get some of it down on paper.”

What a pleasure it was to pull this collection of wise, intimate essays from my own bookshelf a month or so ago, and to revisit my old friend on the page before setting out to meet his spirit at the farm where he lived out the best of his writing days.

What a pleasure it was to pull this collection of wise, intimate essays from my own bookshelf a month or so ago, and to revisit my old friend on the page before setting out to meet his spirit at the farm where he lived out the best of his writing days.

On the road, Lauren and I listened (not for the first time, for either of us) to EBW reading Charlotte’s Web aloud, perhaps the most perfect match-up of author’s voice and material ever. No one could possibly render the contemptuous voice of Templeton the rat with such spot-on accuracy, or so beautifully recreate the dialogue between Wilbur and Charlotte, or offer up such an authentically self-righteous goose gabble as EBW himself. (I know every word of this book, and still it captivates me.) Meanwhile, the miles rolled by. For lunch we ate cheese and crackers and dried apricots in the car, eager to arrive at our destination.

The GPS led us this way and that, through villages, past glimpses of marsh and sea, down one long winding road after another. And then, suddenly, there we were, climbing the back steps, knocking at the kitchen door, being welcomed by Bob and Mary, and ushered right into EBW’s study to hear the story of how the large maps White had chosen decades ago for wallpaper had been hung, in his absence, upside down.

The GPS led us this way and that, through villages, past glimpses of marsh and sea, down one long winding road after another. And then, suddenly, there we were, climbing the back steps, knocking at the kitchen door, being welcomed by Bob and Mary, and ushered right into EBW’s study to hear the story of how the large maps White had chosen decades ago for wallpaper had been hung, in his absence, upside down.

It was a lot to take in: EBW’s office, full now of its current owner’s books and possessions; across the hall, Katharine’s sunnier study, updated but still clearly a space for getting things done; up the steep stairs past original 1700s murals on the walls, to EBW’s bedroom with it’s view across the fields — and, coiled like a sleeping snake in the small closet, the old rope ladder he kept at hand just in case a house fire ever required him to navigate an emergency exit through a window.

From the house and its layers of history, we proceeded out through the “summer kitchen” and into the barn itself. It was tempting to stand there in the dim silence for a while, matching what we saw before us to the description we’d heard EBW read just moments before we arrived:

From the house and its layers of history, we proceeded out through the “summer kitchen” and into the barn itself. It was tempting to stand there in the dim silence for a while, matching what we saw before us to the description we’d heard EBW read just moments before we arrived:

The barn was very large. It was very old. It smelled of hay and it smelled of manure. It smelled of the perspiration of tired horses and the wonderful sweet breath of patient cows. It often had a sort of peaceful smell—as though nothing bad could happen ever again in the world.”

The cows and horses are long gone, of course. And yet, as White himself had once observed about the place, “Certain things have not changed.” There were the farm tools, hanging neatly on their hooks.

Tacked to the wall, a yellowed paper inscribed with a family’s most-used phone numbers, with Henry the hired man’s four essential digits at the top of the list. (Henry stayed on, we were told, for many years after EBW and Katharine were gone, caring for the house and the gardens the way he always had when they were alive, until he, too, departed this earth.) There was the trap door that opened up to the manure pile on the lower level, where Wilbur passed his eventful days.

Tacked to the wall, a yellowed paper inscribed with a family’s most-used phone numbers, with Henry the hired man’s four essential digits at the top of the list. (Henry stayed on, we were told, for many years after EBW and Katharine were gone, caring for the house and the gardens the way he always had when they were alive, until he, too, departed this earth.) There was the trap door that opened up to the manure pile on the lower level, where Wilbur passed his eventful days.

And best of all, perhaps, there was the old, sturdy, thrilling rope swing, the very swing that was much loved and much used by EBW himself, and which he memorialized for all time with his description of the swing in Zuckerman’s barn:

You straddled the knot, so that it acted as a seat. Then you got up all your nerve, took a deep breath, and jumped. For a second you seemed to be falling to the barn floor far below, but then suddenly the rope would begin to catch you, and you would sail through the barn door going a mile a minute, with the wind whistling in your eyes and ears and hair. Then you would zoom upward into the sky, and look up at the clouds, and the rope would twist and. . . ”

Could we take a ride?

Indeed we could.

Indeed we could.

A shady lane led past the garden, alongside the pond, and down through the trees to Allen Cove and EBW’s hallowed writing cottage at the water’s edge. The door was open, as if someone was expecting us.

A shady lane led past the garden, alongside the pond, and down through the trees to Allen Cove and EBW’s hallowed writing cottage at the water’s edge. The door was open, as if someone was expecting us.

It was here, in a plain wooden cupboard hung on the wall, that EBW stored his works in progress.

It was here, in a plain wooden cupboard hung on the wall, that EBW stored his works in progress.

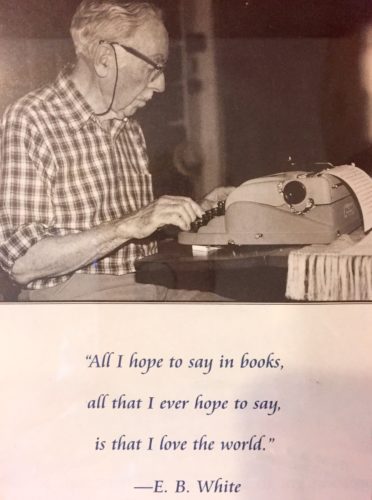

It was here, by a window lifted open to the sea, that he sat alone with his typewriter. And it was here that photographer Jill Krementz captured him at his craft on a summer day in 1976 – perhaps the most iconic, most romantic, best-loved portrait of a working writer ever taken.

It was here, by a window lifted open to the sea, that he sat alone with his typewriter. And it was here that photographer Jill Krementz captured him at his craft on a summer day in 1976 – perhaps the most iconic, most romantic, best-loved portrait of a working writer ever taken.

At the end of the day, Mary told us, Henry would appear at the door to carry EBW’s heavy gray Underwood back up to the house.

At the end of the day, Mary told us, Henry would appear at the door to carry EBW’s heavy gray Underwood back up to the house.

“Why not just leave it down at the cabin?” a friend once asked.

“Because,” the hired man patiently replied, “then he would have to have two.”

Lauren and I lingered for a long time at the cabin. We sat on the hard wooden bench and gazed out the window at EBW’s beloved view of water and sky and shore. We imagined what it might be like to live in the serene old house and to work in this simple, sacred cottage by the sea. We listened for echoes and watched the dust motes dance in the air. And we imagined EBW here – half farmer, half literary gent, as he called himself — breathing eternal life into a pig who wanted to live and the spider determined to save him.

It was surprisingly easy, in this remote, unchanged spot, to conjure the spirit of a writer who passed away over thirty years ago. I remembered exactly where I was when I heard the news of EBW’s death: riding the M bus on an autumn morning from my own overheated, too-small New York apartment to my job as an editor in midtown Manhattan. I saw the front-page notice in the New York Times and felt as if I’d lost both a mentor and a friend.

And now, thanks to countless twists and turns of fate, here I was all these decades later, sitting at his desk. Here I was, looking out his window to the sea, the sound of his voice reading aloud still fresh in my ears. Here I was, having long since left the city for the country myself, having married and raised sons and written books and buried dogs and lost loved ones. Here I was, having learned and survived my own hard, sad lessons about the limits of friendship. And having found, just as Wilbur does, that a grieving heart recovers and that this blessed, beautiful life goes on — a life full of sea breezes and sunrises and sunsets, wonderful books and unexpected adventures, and a beloved daughter-by-choice with whom to share it all.

And now, thanks to countless twists and turns of fate, here I was all these decades later, sitting at his desk. Here I was, looking out his window to the sea, the sound of his voice reading aloud still fresh in my ears. Here I was, having long since left the city for the country myself, having married and raised sons and written books and buried dogs and lost loved ones. Here I was, having learned and survived my own hard, sad lessons about the limits of friendship. And having found, just as Wilbur does, that a grieving heart recovers and that this blessed, beautiful life goes on — a life full of sea breezes and sunrises and sunsets, wonderful books and unexpected adventures, and a beloved daughter-by-choice with whom to share it all.

The post chatting with ghosts

a visit to E.B. White’s farm appeared first on Katrina Kenison.