Remembering Professor James Campbell

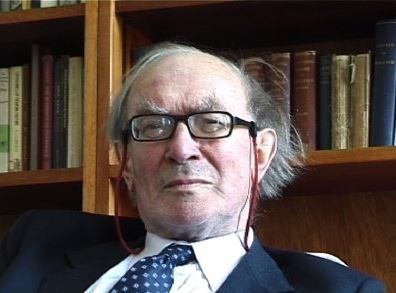

Professor James Campbell, 2009; a still from an interview conducted by Alan Macfarlane

By ALEX BURGHART

I have just returned from a funeral in St Mary���s, Cogges, Oxfordshire ��� a tranquil corner of old England where, to paraphrase Larkin, the place names are all hazed over with flowering grasses and, under wheat���s restless silence, the fields shadow Domesday lines. The bigwigs of medieval history gathered there to say their final goodbyes to Professor James Campbell, one of the finest minds ever to write about Anglo-Saxon history and, perhaps, the last of the old dons.

Many people are donnish. But there was nothing -ish about James���s donnery. He smoked a pipe until he was seventy. He liked a drink before, during and after tutorials (a "swift half" before Hall was not always swift and not always a half). He could be madly disorganized ��� one former student reported seeing his unmarked essay on James���s floor many years after he had graduated. He never learnt to drive and he never used a computer ��� after the typewriter he liked became obsolete all his essays were written by hand. He was intensely myopic and could use his jam-jar glasses to dramatic effect. He needed very little sleep ��� one friend who holidayed with him reported waking up in their Moscow hotel room in the small hours to find him reading the works of the soviet geochemist Vernadsky and puffing on cheap Russian tobacco. He was deeply loyal to his Oxford College, Worcester, which had made him a Fellow when he was twenty-two; he stayed there for forty-two years, never completing a doctorate and migrating straight from "Mr" to "Professor". He was a bachelor until his seventies, when he became a happily married man.

Most of all, he had a wholly remarkable storehouse mind which seemed to contain detailed notes of everything he had ever read ��� and he had read hungrily and omnivorously for a very long time. This reading fuelled a huge flotilla of interests ��� everything and anything from cannonballs to the herring trade to minor Irish country houses to German political thought and beyond. He once said, quite rightly, that "in terms of people teaching well and being useful to the University, people who read a lot are at least, or even more, important than people who write a lot". For his part, he adored teaching ��� he hated it when younger dons considered it a burden ��� and his students adored being taught by him. Many have talked about the experience for the rest of their lives.

In some ways he was a man from a different time. Raised by his grandparents in the rural East Anglia of the 1930s and 40s, he had a deep connection with previous generations and the England that they had inhabited. He had met his great-great uncle who had been born in 1848 and who was a successful bookmaker despite being illiterate ("the only man in my family ever to make any money and he left it, not to one barmaid, but two"), and he told stories about his grandmother's grandfather who had been a "witch-doctor for cattle" and had gone from herd to herd laying hands on sick cows with a tame bantam cock perched on his shoulder as a familiar.

It was perhaps inevitable that such a man, who seemed to know, almost at first quarters, something of the time before the industrial revolution, would develop a deep reverence for and empathy with England's most ancient institutions. A number of his essays profoundly illuminate the sophistication of the late Anglo-Saxon state ��� how orderly, centralized and uniform it was. But he also showed, as the great nineteenth-century constitutional historians had done, how the Anglo-Saxons' shire and hundred courts had required the participation and co-operation of ordinary people and how this participation had "maintained a kind of freedom, of non-absolutism, in the polity". Such readings make Anglo-Saxon history more than interesting; they make it important, because they involve the period in the history of liberty. Indeed, his work consistently showed that much of what is taken to be modernity in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was actually much older (what he often called "very old indeed").

James did not shy away from the consideration of great antiquity. He noted that Domesday Book used much the same system of land assessment that had been in place 400 years earlier when the written record began. He argued that this might simply be the first glimpse of already ancient systems that had allowed for the construction of Maiden Castle hillfort in the first millennium BC and that of Stonehenge in the third. But because he could see equally antique parallels in the organization of Neolithic Ireland and early medieval Denmark, he could detect the possibility of an "Indo-European grammar of government common to the local administration of much of Europe over very long periods, but coming to light and knowledge only late".

Every time I talked with James, I always learnt something that I would not otherwise have known. It meant that I had conversations with him that I could not have with anyone else. And now those conversations cannot be had. In his Festschrift, his friend and former pupil, the late distinguished Anglo-Saxon scholar Patrick Wormald, wrote that "James Campbell���s importance lies not in the vast amount that he knows, nor even in the unexampled richness of what he writes, but in how he has taught historians of early times to think". That importance lives on.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers