Stick and stickability

By MICHAEL CAINES (no pun intended ��� ed.)

There is a modest tradition of walking sticks propped in literary corners ��� in the writings of Leigh Hunt, Richard Steele and a few others. Steele didn't always trust them: "a cane is part of the dress of a prig", he suspected. Wounded soldiers aside, there were too many "peaceable cripples" who, "in this warlike age", "think a cane the next honour to a wooden leg". Hunt was more defensive of the innocent instrument itself. He felt the insult was misplaced when people were called names such as "a poor stick, a mere stick, a stick of a fellow". "We protest against this injustice done to those genteel, jaunty, useful, and once flourishing sons of a good old stock."

There is a self-flattering Edmund Gosse anecdote about Tennyson, as published in the TLS in 1904, in which the younger man seeks to impress the Poet Laureate with a fine line about ��� what else? ��� Rosicrucianism, likening the mysteries of that secret society to the mysteries of the art of poetry. The poet's response was gratifying: "He paused to listen, and then beat his walking-stick upon the gravel with fervent approval". Walking sticks, it seems, are not merely an aid to perambulation . . . .

For Dickens, whose own sticks survive in various museums, sticks could have personalities of their own. Jenny's crutch-stick in Our Mutual Friend, at one point, "seemed to entreat for its owner to come in and rest by the fire". In the same novel, Boffin's "seemed to be whispering in his ear". Around the same time, Punch patronisingly advised the frugal young lady who wished to adopt a cane for fashion's sake to "convert her last year's parasol stick into a new walking one, and so save Papa the cost". Although equally chappish, Hunt reckoned the stick to be an ancient and universally useful invention. Hence its diversification in modern times, with three related categories of use: "to give a general consciousness of power"; "to help the demeanour"; and "to assist a man over the gaps of speech ��� the little awkward intervals, called want of ideas".

The eighteenth-century stick could be a means of attack or defence ��� the ursine Dr Johnson's stick was meant to be a considerable deterrent ��� but Hunt had in mind the usefulness of a stick to "any one who has known what it is to want words, or to slice off the head of a thistle". "How his foot keeps time to the switches! How the passengers think he is going to ride, when he is or not! How he twigs the luckless pieces of lilac or other shrubs, that peep out of a garden railing! And if a sneaking-looking dog is coming by, how he longs to exercise his despotism and his moral sense at once, by giving him an invigorating twinge!"

Sticks need not be so energetic. In more recent times, when the Australian writer Donald Horne had to stop for a rest in the street, he switched from walking-stick mode ("using it as a rudder on the flat and as alpenstock on slopes . . . not to mention the swinging of the tip with every second or third step to show who is in control") to "shooting-stick mode". He would pause to take in the scene, "imagining a painting", only for strangers to ask if he knew where he was, and if he needed help getting back to his nursing home. Unfortunately, "to the uninformed eye, I can seem an old man lost". There is more telling meditation on age and its supports in Antony Thwaite's poem "In the Vicinity of the Crank-house".

This is a reminder of Coleridge's story about the "strange walking-stick, five feet in length" he bought from a countryman in in Cambridge, in 1794. This stick, he could claim, "a most faithful servant it has proved to me"; "sudden affection" swiftly "mellowed into settled friendship". When it went missing from the inn where he was staying in the Welsh town of Abergele, during a tour with a college friend, and an alarmed search revealed nothing, he resorted to giving the following lines to the town crier:

"Missing from the Bee Inn, Abergeley [sic], a curious walking-stick: on one side it displays the head of an eagle, the eyes of which represent rising suns, and the ears Turkish crescents; on the other side is the portrait of the owner in woodwork. Beneath the head of the eagle is a Welch wig, and around the neck of the stick is a Queen Elizabeth's ruff in tin. All down, it waves the line of beauty in very ugly carving. If any gentleman (or lady) has fallen in love with the above-described stick, and secretly carried off the same, he (or she) is hereby earnestly admonished to conquer a passion, the continuance of which must prove fatal to his (or her) honesty; and if the said stick has slipped into such gentleman's (or lady's) hand through inadvertence, he (or she) is required to rectify the mistake with all convenient speed. GOD SAVE THE KING."

This is where a Horne-like figure comes into view. Coleridge continues:

"Abergeley is a fashionable Welch watering-place, and so singular a proclamation excited no small crowd on the beach, among the rest a lame old gentleman, in whose hands was descried my dear stick. The old gentleman, who lodged at our inn, felt great confusion, and walked homewards, the solemn cryer before him, and a various cavalcade behind him. I kept the muscles of my face in tolerable subjection. He made his lameness an apology for borrowing my stick, supposed he should have returned before I had wanted it, &c . . . ."

For Coleridge, it was a fine bonus that a "very handsome young lady" in a coach asked for the copy of the bill Coleridge had given to the crier. "I acceded to the request with a compliment, that lighted up a blush on her cheek, and a smile on her lip."

By contrast: the saddest of literary sticks must be Virginia Woolf's. It accompanied her on her last walk to the River Ouse in 1941. Leonard found it on the bank, and it has now made its way to the New York Public Library.

My only excuse for taking this idle thought for a walk ��� swiping at shrubs, but no dogs, as I go ��� is an auction. You can view now (and buy tomorrow, should you wish and have a few hundred or thousand quid going spare) items from the collection of Roy Moore, a late "rabologist" (collector of walking sticks).

Over the surprisingly short span of two years, according to Chiswick Auctions, Moore acquired over 400 walking sticks from Europe and the US, many of them exquisite, rare and unusual. The Starck Barnes & sons walking stick pictured below, for example, is topped with a Royal Navy roundel and doubles as a flute:

This bamboo cane, meanwhile, of Chinese manufacture, doubles as an opium pipe:

That makes it not dissimilar in doubleness from this cheaper "folk art smokers companion" equipped with a clay pipe:

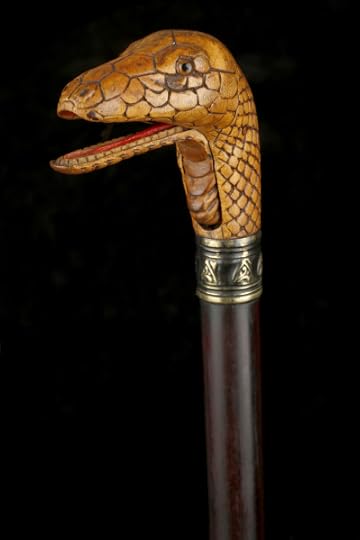

Whereas this reptilian curiosity in rosewood is perhaps only spring-loaded in order to impress, or terrify, the grandchildren:

I'd like to think that Leigh Hunt, the connoisseur of the "rhabdosophy, sceptrosophy, or wisdom of the stick", would have enjoyed all this ��� even if the porcelain handles weren't exactly what he meant about a stick's ability to "help the demeanour".

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers