When adoption meant forever

If Australia’s forced adoption practices of the 1950s to the 1970s were questionable, what happened around the turn of the twentieth century was utterly mind-blowing.

If Australia’s forced adoption practices of the 1950s to the 1970s were questionable, what happened around the turn of the twentieth century was utterly mind-blowing.

I have just finished reading a meticulously-researched account of so-called adoptions in the 1880s by law professor Annie Cossins. The Baby Farmers focusses on the shocking case of Sarah and John Makin of Sydney, who made their living from the misfortunes of young women who had babies out of wedlock. The Makins’s sordid activities – the murder and burial of no less than 13 illegitimate babies in the backyards of the houses they rented – resulted in a death sentence for John and life imprisonment for Sarah.

Apart from the specifics of the Makin case, the book provides enlightenment about the bad old days of the colony, when women had babies by the dozen (due to no means of contraception barring abstinence). There was never enough money or food for a growing family and sexually transmitted diseases were rife.

The jaw-dropper for me was the high infant mortality rate. Infant deaths were so common that when a baby died, no-one questioned what happened. The entire matter was swept under the carpet. It was no wonder children died in droves. Vaccinations were yet to be invented and diseases such as diphtheria, whooping cough, scarlet fever, measles and influenza swept unchecked through communities. Babies who weren’t breast-fed were given an infant formula that consisted of watered-down Nestlé’s sweetened condensed milk.

In the 1880s, the birth and death of a child was not necessarily registered by its parents. There was no regulation of adoptions or fostering arrangements either. Pregnant women (married or not) received little or no medical care and babies were commonly born in private residences with the assistance of another woman as midwife.

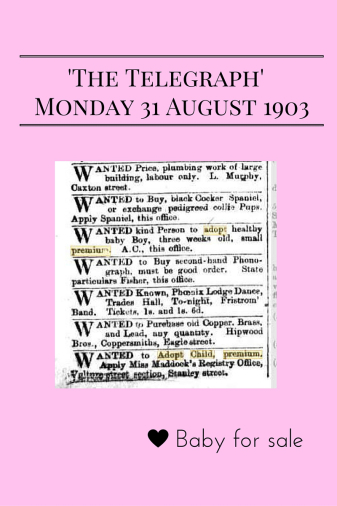

Babies born out of wedlock were truly regarded as ‘bastards’. An unmarried mother had no choice but to dispose of the baby in whichever way she could afford. Amongst the newspaper ads for scrap metal, dogs, horses, and plumbing work were requests to take illegitimate babies. The ads were curiously worded, often referring to a ‘kind Lady’ and payment of a ‘premium’.

According to Annie Cossins, the ads were written in code to reflect the wishes of the mother and the baby farmer. If a one-off payment – a ‘premium’ – was offered together with the word ‘adopt’, this meant that the transaction was permanent. Some unmarried mothers hoped an occasional visit would be part of the adoption plan or else they might elect to pay a weekly fee for the ‘kind Lady’ to care for their infant in the hope of retrieving it at a later date.

In reality the ‘premium’ – generally a few pounds sterling – was a fee to dispose of the child. Most baby farmers took in more children than they could possibly care for. The babies soon died of disease, malnutrition or neglect, paving the way for the baby farmer to take yet more children. In the case of the Makins, the infants’ bodies were wrapped in cloth and buried in the backyard of the houses they rented. Needless to say, the couple moved frequently, not only to avoid paying rent but also to escape the awful smell.

At the end of her book, Annie Cossins sums up the sad state of affairs in words I couldn’t hope to improve. Here is what she wrote.

Sarah’s and John’s crimes were also the crimes of a society that condoned infanticide while, paradoxically, stigmatising unmarried mothers. The legal status of an illegitimate child was described as ‘filius nullius’, child of no-one, which sums up the legal and social reality of those times. Since these children had no legal status, it is hardly surprising they had little or no social value. Life was cheap for illegitimate babies. Baby farmers provided an unsavoury but necessary service that filled the vacuum left wide open by government policies, the market economy and the limited assistance available through charitable organisations.

Sometimes we need to look back to see just how far we’ve come.