Some good news of a non-book kind. Sort of.

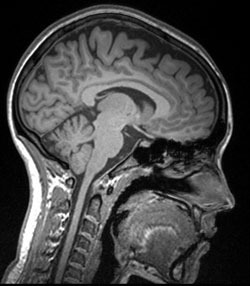

Today I had an appointment with my neurologist, who gave me the results of my recent MRI scan. Compared to my scan of March 2009, it showed a decrease in both the number and the size of the lesions in my brain.

This is A Good Thing: it means my relapse rate has been stalled, and my poor beleaguered body has been able to start repairing some of the myelin damage caused by MS.

How much of this is due to the Tysabri infusions I've been on for the last two years, and how much is due to me finally acknowledging that the day job with its horrendous commute was no longer sustainable, I'll probably never know. Bit of both, most likely.

Since I gave up work I've been able to get the rest I need, and be kinder to myself. That means on a shitty day, if I don't get out of bed until 11am, so be it. On good days I'm up at 7:30. Most days it's somewhere in between. Either way, these results confirm that quitting my job and changing my treatment regimen were the right things to do.

One small winged insect in the ointment: Tysabri (natalizumab) has an immuno-suppressant effect, and some immuno-compromised people, like MS patients and transplant recipients given anti-rejection drugs, have gone on to develop PML, or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, which is often fatal.

The science bit: PML is triggered by the JC virus, which is widespread in the general population, lying latent in the gastrointestinal tract. In an immuno-compromised patient it can "reactivate" and trigger PML, because JCV can cross the blood-brain barrier and directly infect (and destroy) the oligodendrocytes which protect the myelin sheath around the nerve-cells' axons in the central nervous system – that's your brain and spinal cord.

I was blood-tested last week to see if I've been exposed to JCV. The general risk of developing PML is about 1 in 1,000; if I've been exposed, that rises to about 1 in 400. Given that somewhere north of 70% of the population will have been exposed to it (usually in childhood) this, as you can imagine, gives me some food for thought.

I've had two very stable, relapse-free years with Tysabri. Back in 2009, when it became apparent that the beta-interferon therapy was no longer working, I looked at the risks, weighed up the benefits, and decided Tysabri was the best treatment option for me and my highly-active at the time MS. I still think that is the case, but when the blood-test results come in, if my risk profile changes, I am going to have to think through my choices once more and see if I'm still comfortable with it.