Revise, he said

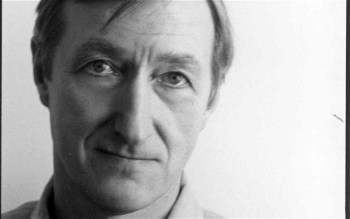

[Manuscript page from Julian Barnes’s new novel The Noise of Time. Barnes was interviewed about his writing process for LitHub by John Freeman, who took the photo.]

Other eyes seem intrinsic to revision in writing’s drafting process.

You start off with different possible tonalities and the right one only gradually comes into play.—novelist Julian Barnes, in the interview about his process on LitHub.

[Master reviser: novelist Barnes.]

When you ask someone to read your work, I tell students, convey what concerns you have. Readers tend to report what they noted anyway, maybe errors underscoring their own expertise. Which often consists of the baggage they carry from past English teachers—rules of thumb enforced as rules. “I was taught never to use a sentence fragment!” “You can’t begin a sentence with and.” “Semicolons look too fussy.” So, I say to my classes, “Be sure to get your questions addressed.”My students seem to receive their best advice from people who regularly write. In the college setting, this means other students. On average, any student writes much more than the typical American. Students in the same writing class tend to convey the sharpest insights, of course, since they also know that particular genre. People lacking confidence as readers usually don’t do much writing themselves—especially “creative” writing: any kind of essay, narrative or personal journalism, poems, stories. Which means, I think, they doubt their own experience of reading the work. Maybe they think it’s their fault when they trip over infelicities. Or they wonder about gaps or TMI but, unaware of how much rethinking writers do, assume content is fixed.

Historically, taste has been developed by steady, close reading of quality stories, poems, essays, and novels. Every reader helps, though. Suggesting one better word is huge. The most comprehensive reader of my work I’ve ever had was a fellow teacher. She taught literature and composition and also published scholarly essays. She read a lot of good books, both classics and current; she constantly graded and edited student essays; all the while, she worked to make her own writing clear, colloquial, trenchant. The judgment and technical expertise she brought to bear on my work was humbling. But one person, even if she’s a great editor, isn’t enough. Everyone catches something. At least three readers seems ideal.

If only by salving loneliness, a writing posse buffers two things about writing that irk me. The first: unclear aesthetic choices—where to begin? what’s vital versus extraneous? which passage to end on? At first, I hate to admit, I find such uncertainty actually painful. If I stick with a piece long enough, however, the distressing issue clarifies; at least, I’m able to justify my choice. Sometimes a reader can help, if I point out the choice I’ve made and the other option(s).

The second vexation: how late into the writing process my basic errors persist: awkwardness, lack of clarity, poor word choice, unclear timeline. Here, my readers always help me take work to a new level. While I’m greedy for this boost, my need for it perturbs me—why can’t I catch everything? Just recently, someone noticed I’d used “defines” in a similar, distinctive usage three times in a 12-page essay. This was after I’d worked on the piece for two months. Reading aloud, a key part of my process, would have caught it. Actually I had read it aloud, but I’d lingered so long over its “final” stage that I’d added bits, moved sentences, substituted words. My friend’s catch defined embarrassment for me. Lesson learned, I hope.

Do you have a writing posse? Friends you trade work with? How have other eyes helped your writing?

[The LitHub interview with Julian Barnes also features this John Freeman photo. Does Barnes write in longhand first, before typing up his manuscript? Appears so.]

If you make the commitment to perseverance and repetition, you will have words in front of you, you will have sentences. The wonderful thing about writing is it can always be made better. But it can’t always be made. If you can make it, you can make it better. Translate writing’s mental problems into a physical problem, because writing’s mental problems will never be solved.—Adam Gropnik on Charlie Rose’s “Green Room” feature at YouTube, below.

The post Revise, he said appeared first on Richard Gilbert.