Deconstructing Virtue

The once chic term "deconstruction" is derived from Heidegger's term destruktion because the latter didn't actually mean "destruction" as in English. It meant something more like "disassembling" a mechanism in order to adjust or to fix it. Jacques Derrida therefore decided to modify the term as "deconstruction." One undoes the construction of terms, ideas, texts, philosophies, whole worldviews. In this way one sometimes discovers dimensions, shades of meaning, that have been suppressed or neglected, then forgotten, with a sad loss in meaning and utility. Perhaps the most famous of Heidegger's destruktionen or deconstructions was that performed upon the word "truth," in its Greek original aletheia. It breaks down into elements suggesting "removing forgetfulness." Remember the River Lethe, the River of Forgetfulness, that new entrants into Hades were required to sample? Truth is the revealing of the forgotten. That's certainly Plato's epistemology in a nut shell, right? All deconstructions seek to uncover such an underlying reality by taking a word or notion down to its basic roots and discovering thereby a dimension of meaning that has been overshadowed but which, when you think about it, has lingered unobtrusively nonetheless, still imparting, or trying to impart, an added element of meaning. This, I gather, is the basis for the attempt of the later Heidegger to read poems and to gain through them a new vision of the vista of truth the original poets saw and to draw new insights, new aspects of Being, from it.

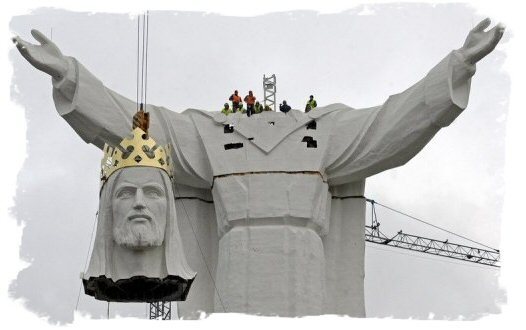

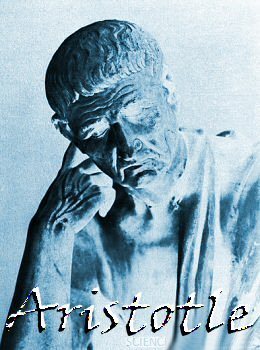

In any case, I want to suggest briefly the importance of another crucial word: virtue. The Latin virtus translates the Greek arête, which also means power and ultimately implies that moral virtue, too, is a kind of power. When Jesus is said to have involuntarily healed the woman with a hemmorhage (Mark 5:24-34), then sensed that "power had gone out of him," the word for power is dunamis, but the Latin Vulgate renders it with virtus. And this represents a deconstruction because it invites as its explanation Aristotle's teaching concerning morality as a power, ability, or skill. He discusses the subject in the Nichomachean Ethics (The Ethics, dedicated to his nephew Nicomachius).

Aristotle, for example, holds that we cannot expect little children to have developed any moral sense of their own. We hope that they will one day, but to start them off right, we must teach them what to do and not to do by command and by rote. "Because I said so, that's why." We don't want them to learn the hard way, by putting their hand on the stove. That will teach them, but we want to warn them and hope they'll take our word for it. Eventually we can reason with them and can explain why A is a wise course of action, and why B, by contrast, is not. Even better, we aim for the day when our children will not only see why we thought our moral rules to be right, but will also be able to evaluate for themselves whether we were right about it — and to reason out their own rules. They will have learned the skill of morality.

What about keeping moral rules, whether ours or theirs? Aristotle explained that we must first decide the right attitude, reaction or action and determine to shape our behavior into conformity with it, even if we feel we are play-acting. That does not make us hypocrites. No, it is the way to reprogram ourselves so that what we believe in our heads to be right will penetrate our hearts and become second nature. It will finally become spontaneous, our default behavior. This, by the way, is why the "daily affirmations" of self-help groups, often ridiculed ("I'm good enough, I'm smart enough, and, doggone it, people like me!"), are by no means silly. They represent good Aristotelian strategy. You are reprogramming yourself, refashioning your habits of thought, feeling, and reaction.

Thus virtue, morality, is seen to be a power and a skill that one may cultivate and strengthen. I say this is how morality ought to be taught. And I further believe that Humanism has a special mission to teach such morality. Let me back up and try to explain why.

I see three basic approaches to moral thinking, each claiming many adherents. There is the traditional ethic of religion: deontological ethics. This means "duty ethics." The moral agent/actor obeys certain rules because an authority has promulgated them. God gave the Torah to Moses. Shamash gave the Code to Hammurabi. Apollo gave his law to the Greeks, etc. We are bound to obey the gods. (And this led Socrates to ask the theology-destroying question whether a thing is right because the gods love it, or if the gods love it and that makes it right. Kids, don't try this one at home, er, I mean in church.) Our duty is to know the rule, and we are judged by our obedience or disobedience whether or not we knew our duty. This is what Paul Tillich, following Kant, called "heteronomy," an alien law imposed upon the conscience from without. There is always the danger of stunting moral growth here in that we may obey the commandment simply out of fear of the repercussions if we do not. And that threatens to make moral obedience into mere lip-service and cringing hypocrisy.

Humanists have embraced the alternative ethical approach of teleological or utilitarian ethics. What is right is that act which brings the greatest benefit to the greatest number (or that which was intended to, as far as results could have been foreseen). The telos, the goal, of an act is what matters. And we humans must use our best wisdom to decide what that is. Situation ethics, obviously, is a type of teleological ethics. Remember Kant's dilemma? Suppose I knock furiously on your door, looking over my shoulder, and plead with you to let me hide in your basement, and you let me. Then, minutes later, here comes a knife-wielding enemy of mine demanding to know if you have seen me. What are you to do? Incredibly but consistently, Kant said your only obligation is to tell the truth, not to lie. "Yeah, he's in the basement." That is deontological ethics in its most stark and ruthless form! A utilitarian, on the other hand, would have no trouble deciding that in this particular case telling the truth is going to do no one any good, so his obligation is to save life. Thus he is obliged in this case to lie. "Price? Sorry, never heard of him! Have a nice day!"

The third option, while not incompatible with the others, is virtue ethics, which centers upon the moral character of the agent. What will the choice of a particular act do to one's character? To one's integrity? Are certain major acts degrading or destructive of character? Will certain patterns of minor acts, comprises, have the same desultory result? "I could tamper with that evidence to make sure the guilty party is punished, but what gives me the right? I could torture that terrorist to get vital information, but wouldn't that reduce me to his level? Could I live with myself if I did this or that?"

Both teleological and virtue ethics are "autonomous" rather than "heteronomous." They represent one's own law and morality, not someone else's. I like that. But I am often disturbed to observe Humanists acting from teleological, utilitarian ethics and thinking it is sufficient. They seem to me to be neglecting virtue and character. The result is, for example, what appears to be the unscrupulous machination of politicians who openly boast about their liberal policies to their constituents, the people, the nation, the majority, minorities, whatever. As individuals they may be exposed as rascals, adulterers, liars, embezzlers, tax cheats, etc., but their defenders maintain that these "personal" matters just do not bear on their job performance. They ridicule those who see the possible social/political/military implications of a lack of personal integrity. Such objectors are denounced as Puritans and prudes. Worse yet, as "conservatives." I was stunned when, after the commencement of the War on Terror in 2001, some fellow Humanists began to label anyone who believed in "Right and Wrong" as "fundamentalists" and apocalyptic nuts. I have news for you: if you don't think there is any such thing as "good," I don't know on what basis you mean to calculate "the greatest good for the greatest number."

We have to work out, I think, some sort of amalgam position. If there is nothing to duty ethics, why bother to be utilitarian? We believe we have a duty to benefit other people, as many as possible. And we must safeguard our own souls (an old term for integrity, nothing more) in the process. We cannot patronize others by usurping their own decisions.

If we take all this into consideration, we will have a persuasive package. I believe it is difficult to preach morality because it always sounds condescending and, worse yet, heteronomous: the imposition of the will of one's masters (teachers, parents, government). Who doesn't chafe at that? It is practically one's duty, in the interest of preserving one's integrity, to rebel. But if we were to approach moral education the way Socrates, Aristotle, and Epicurus did, we could show that it is each individual's duty to seek his own interests. Who does not seek his own interests, to attain what will be good for him? And everyone should! It's no one else's job, that's for sure. The trouble is that people lack knowledge of what course of action would be most effective. Certain acts would benefit the individual in the short run but erode the social fabric (and one's own integrity), in the long run. The goal is fine, but there's got to be a better way. That's why Socrates said "Knowledge is virtue."

Kant spoke of our "categorical imperative" to do as duty dictates. If a thing is right, we must do it even at great cost. (Of course we all agree there are some such occasions, like giving one's life for family or country.) Any other basis for decision, Kant said, is merely acting on a "hypothetical imperative." Mere strategy. "Do you want to avoid rush hour traffic? Then I'd take this alternate route." He dismissed teleological ethics as no ethics at all, merely pragmatism in ethical clothing.

But I think we ought to show students, our children, prisoners, whoever needs moral education, that morality is a hypothetical imperative as well as a categorical one. Your duty is to pursue your own welfare. We all need you to do it! We as a society are counting on you! Likewise, I am responsible, duty bound, to seek my own benefit, improvement, personal growth and welfare. You can't do it for me. All of us are like musicians in an orchestra. Each must play his or her own music, not the other guy's, if the piece is to come out sounding right! I want to seek my own good. I want you to seek yours. And part of my good is to enjoy your friendship, which is why "It is more blessed to give than to receive." I get more of a kick out of it than you! Is that "selfish"? Who cares? Works out pretty well if you ask me!

Evangelists use the simile that gospel witnessing is "just one beggar telling another where to find bread." I am saying that is what moral instruction ought to be like. There will be a moral and practical unity between self-regard (including care for one's integrity, virtue, and moral growth), regard for others' welfare, which gratifies us, and one's duty to both. Everybody wins! Virtue takes practice. It is training to win the game, and it is a game no one will have to lose.

So says Zarathustra.

Robert M. Price's Blog

- Robert M. Price's profile

- 237 followers