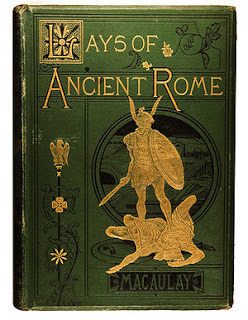

The Lays of Ancient Rome

I want to put in a plug for the old writers. You know how much I love old writing, and dead authors, and all that. I find the death of the author lends a kind of potency to good literature. A book is a man's far more significant gravestone that he leaves behind.

I want to put in a plug for the old writers. You know how much I love old writing, and dead authors, and all that. I find the death of the author lends a kind of potency to good literature. A book is a man's far more significant gravestone that he leaves behind.I just finished a battered old school edition of Thomas Babington Macaulay's The Lays of Ancient Rome - a battered old copy published in 1913 by Charles Merrill, an edition meant for schoolboys. It's a very nice copy: blue, cloth-bound, its pages yellowed and musty-scented from age, and I found that the beginning decrepitude of the book, its smallness, and its general feel of a type of book confined to past ages lent to the words inside an even greater potency. The whole thing felt old and, though old, alive. When I first cracked it open and the rush of musty book-smell wafted out at me, I was giddy.

Lars Porsena of Clusium

By the Nine Gods he swore

That the great house of Tarquin

Should suffer wrong no more.

By the Nine Gods he swore it,

And named a trysting day,

And bade his messengers ride forth,

East and west and south and north,

To summon his array.

The little school book boasts Horatius, The Battle of Lake Regillus, Virginia and The Prophecy of Capys. I was familiar with the fact that, as a boy himself, Winston Churchill had been made to learn Horatius by heart; but even without this knowledge, I think Porsena's vow would have opened the poem no less grandly for me.

With the vividness of good poetry, Horatius opens depicting the gathering of the Etruscan League against Rome. Horatius is not a lengthy poem (not like The Idylls of the King); Macaulay chooses his words perfectly, his cadence lending a marching-beat splendour to the pictures his words make. The Etruscan League gathers, thousands and thousands of soldiers from the twelve chief Etruscan cities, marching on Rome - "from the rock Tarpeian" the Romans watch the advancing devastation of the enemy host. Time is scarce, resources limited. Hopelessness hangs in the air. The city is choked with refugees from the surrounding countryside and the Senate, in dismay, watches their doom come marching down the road toward them.

And nearer fast and nearer

Doth the red whirlwind come;

And louder still and still more loud,

From underneath that rolling cloud,

Is heard the trumpet's war-note proud,

The trampling, and the hum.

And plainly and more plainly

Now through the gloom appears,

Far to left and far to right,

In broken gleams of dark-blue light,

The long array of helmets bright,

The long array of spears.

All seems lost, but the life-vein of the city could be its salvation: the Tiber might prove to gain them time, if only the bridge can be cut before the Etruscan host can swarm across. Horatius, for whom the poem is named, stands out as an image of pure Romanhood against the pitiful backdrop: faithful to the last, caring nothing of himself, whether he lives or dies, only that he does his duty for Rome.

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his Gods..."

It is the story of a very brave few holding back a tide of many. Even the enemy, awed by the display of faithfulness and prowess by Horatius and his friends, cheer them on as they throw down champion after champion sent against them.

With weeping and with laughter

Still is the story told,

How well Horatius kept the bridge

In the brave days of old.

Longer, and even more intense, follows The Battle of Lake Regillus. Several of the characters from Horatius reappear in this poem. The first poem charts the terror of pending confrontation, the second brings the forces to a head, Rome against the Etruscan League, and opening with the vantage point of time having gone by, heralding in the poetic story with the distinct overtones of victory.

Gay are the Martian Kalends:

December's Nones are gay:

But the proud Ides, when the squadron rides,

Shall be Rome's whitest day.

The call is to remember, in the name of the Great Twin Brethren, the Battle of Lake Regillus, the slaughter, the sacrifice, the heroes who lived and died there. The ghosts of dreams, the ghosts of battlefields, the ghosts of patrician families whose names have long mouldered into the dust, and the geniuses of gods bolt across the pages in rhyme and metre. The poet takes the reader through the planning of battle to the joining of battle, and describes many of the heroes who were met there on the field: the Dictator Aulus, and Æbutius Alva Master of the Knights, Mamilius of the Latian name whose helmet shone like red-gold flame, Lavinium and Laurentum, and Herminius on black Auster, Titus and false Sextus, and many, many more. The pieces are set, the board is ready - battle is engaged.

"On, Latines, on!" quoth Titus,

"See how the rebels fly!"

"Romans, stand firm!" quoth Aulus,

"And win this fight or die!"

Perhaps the most stirring encounter of heroes, and the most tragic, is that of the Latian Mamilius and the Roman Herminius - the latter had helped keep the bridge in Horatius. The dark-grey charger and black Auster dash at each other, the whole battle swings and pauses round the warriors to watch, as if the earth has caught its breath in collective horror. It does not last long. The blows are swift and sure, and fatal -

And still stood all who saw them fall

While men might count a score.

But the tone of victory and defeat is carried on in the wake of the deaths of these two mighty warriors. The deed is done, but the poet follows the terrified homeward flight of Mamilius' grey horse: a riderless horse running into its own paddock is a potent image of defeat, and the people of Mamilius' Tusculum understand the image all too well.

But, like a graven image,

Black Auster kept his place,

And ever wistfully he looked

Into his master's face.

Black Auster remains over his master's fallen body, faithful even beyond death. The message of his stalwart nature, though brief, is powerful, and the reader's heart is captured by Herminius' horse so that, when the Latian Titus leaps to grab the horse's reins, the outrage is felt keenly. Furious, the Dictator springs at Titus and lays the young man in the dust, dead. Dismay falls on the Latian host. The wind is up, the tide is turning; and as Aulus swears revenge with black Auster upon Herminius' death, out of nowhere ride two splendid young warriors, in armour white as snow, on horses snowy-white. The grim face of a battlefield takes on a suddenly unearthly aspect and, like a dream, everything starts slipping: spirit and earth shift against each other, trying to fit, not quite matching up.

"By many names men call us;

In many lands we dwell:

Well Samothracia knows us;

Cyrene knows us well.

Our house in gay Tarentum

Is hung each morn with flowers:

High o'er the masts of Syracuse

Our marble portal towers;

But by the proud Eurotas

Is out dear native home;

And for the right we come to fight

Before the ranks of Rome."

So answered those strange horsemen,

And each couched low his spear;

And forthwith all the ranks of Rome

Were bold, and of good cheer.

The last charge is driven home, by Vesta's hearth, by the golden shield of Mars, driven home into the invading ranks of the Etruscan army, with the two mysterious white horsemen in the lead, slaying like there has never been slaughter before, and Aulus on black Auster hard behind them. The tide is turned, the

battlefield belongs to Rome: the day is won. The Roman host sweeps up the wreckage of the Latian army, but when those strange horsemen are looked for, they are not to be found.

battlefield belongs to Rome: the day is won. The Roman host sweeps up the wreckage of the Latian army, but when those strange horsemen are looked for, they are not to be found.But on the road to Rome are spied two gentlemen on horseback, their armour scarlet with blood, their horses bloody-red, and they announce to the fearful people in the city that the day is theirs, and that on the morrow their Dictator will ride home in triumph with the ragged corpse of Etruria's government dragged along behind him. The city is thrown into the ecstasies of joy, and the word flies throughout the countryside. But looking neither right nor left, steady on their course, the two horsemen ride on up into the Forum, bedecked with the falling laurel leaves and flowers that the wind brought off the cities garlands to them. They pause and wash their horses at Vesta's spring, then remount, all in silence, and ride through Vesta's door.

Then, like a blast, away they passed,

And no man saw them more.

The Great Twin Brethren had come and gone, and won the day, and Rome did not forget.

The next lay, a tragedy, is a brief one; only fragments of it are given in the text. Virginia is the story of a Rome which is losing its model citizens, a Rome without the Tribunes to uphold the right of the common man in the face of patrician oppression.

This is no Grecian fable, of fountains running wine,

Of maids with snaky tresses, or sailors turned to swine.

Here, in this very Forum, under the noonday sun,

In sight of all the people, the bloody deed was done.

This is a story of greed and innocence, sorrow and rage. Young Virginia, the picture of innocent feminine youth, walking through her own little world, is spotted by the wicked patrician Appius Claudius. His wealth is not enough, his power is not enough: that single dewy morning-star, which ought to have been out of his reach, had to be his. A lament for Virginia! She leaves her home in the morning, bound for her school and the duties of the day - and without warning up comes Marcus, Claudius' client, and grabs her by the arm. Her frightened screams draw a hasty crowd. Everyone knows Virginia, everyone loves Virgina; but what can they do against the likes of Appius Claudius? They have no Tribunes to defend their cause, they have no voice to lament their troubles in politics. Hopelessness hangs in the air.

Of a sudden young Icilius springs upon the scene, who had been a Tribune himself once, who was betrothed to Virginia. In a rage he conjures up the memories of the heroes who had gone before: was this why they had died, so that girls like Virginia could be snatched away by greedy paws? Think well on your fate, Romans - take a stand, or be slaves forever!

"No fire when Tiber freezes; no air in dog-star heat;

And store of rods for free-born backs, and holes for free-born feet.

Heap heavier still the fetters; bar closer still the grate;

Patient as sheep we yield us up unto your cruel hate.

But, by the Shades beneath us, and by the Gods above,

Add not unto your cruel hate your yet more cruel love!"

Icilius' speech throbs through the text: the last agonized, impassioned words of a young Rome. He ends his speech and the poem is broken, picking up again with Virginius, the girl's father, drawing her to one side of the crowd. There is a third option, a third way out of their predicament with Claudius, and Virginius knows it. He calls up memories of her childhood, he calls up his own love for her: the agony of a father saying his last farewell is in all his words.

"Then clasp me round the neck once more, and give me one more kiss;

And now, mine own dear little girl, there is no way but this."

With that he lifted high the steel, and smote her in the side,

And in her blood she sank to earth, and with one sob she died.

Stunned silence fills the Forum. The tension of a summer thunderstorm about to break crackles horrified in the air. Virginius breaks the silence only, calling for justice in the name of the Shades to be done between himself and Claudius. Stricken, but steadfast, he departs. In a fearsome rage Claudius leaps up, screaming for anyone and everyone to apprehend Virginius; but the crowd only falls back in silent respect to let the grieving father pass. The tertium quid has been taken: wickedness has been cheated, and the spark of Roman character is allowed to pass unhindered from the scene.

But Appius Claudius wants the last word. A funeral procession is made for the lovely corpse.

They brought a bier, and hung it with many a cypress crown,

And gently they uplifted her, and gently laid her down.

Decked out in the laurels of death, wreathed in cypress, Virginia's body is borne through the Forum. But Claudius is all mockery. He despises the gesture of respect shown by the crown, and commands his lictors to send the people home and bear away him the corpse. The summer thunder breaks. As the lictors advance the crowd gives tongue, growling low like an angry dog; when the lictors bare their weapons, the storm breaks. Incensed, outraged, the crowd turns on Claudius' twelve men. A Roman shield-ring hangs tenaciously about the bier as the crowd fetches whatever is to hand that can be made into a weapon.

'Twas well the lictors might not pierce to where the maiden lay,

Else surely had they been all twelve torn limb from limb that day.

Furious, Appius Claudius strives to speak, to be heard above the din of outrage and the voice of Roman feeling. But each time he was shouted down.

And thrice the tossing Forum set up a frightful yell;

"See, see, thou dog! what thou hast done; and hide thy shame in hell!

Thou that wouldst make our maidens slaves must first make slaves of men.

Tribunes! Hurrah for Tribunes! Down with the wicked Ten!"

The people have the last word, as they will always do when oppressed beyond their endurance. With stones and rods they send Claudius home, a wretched, battered sight, robbed of his desire and his image of power. The tragedy lingers, but justice has its way in the end.

...every Alban burger

Hath donned his whitest gown;

And every head in Alba

Weareth a poplar crown;

And every Alban door-post

With boughs and flowers is gay:

For to-day the dead are living;

The lost are found to-day.

With gaiety, thanksgiving, and celebration The Prophecy of Capys, the last lay, unfolds on the page. The prophecy harkens back to the early days of Rome, to the settlement on the banks of Alba Longa and the conquests of the twins Romulus and Remus. Many and magnificent are the exploits of Rhea's boys, of Mars' sons, of the she-wolf's little man-cubs. With spear and sword adorned each with the head of a foe, the brothers return triumphant to their old grandsire's hall. At the gate sits Capys the sightless seer; at the advance of Romulus upon the hall the prophecy grips the seer - a splendid, eerie sight to witness - and the luck and life to come of Rome is disclosed with a strange and heady seriousness.

"From sunrise unto sunset

All earth shall hear thy fame;

A glorious city thou shalt build,

And name it by thy name:

And there, unquenched through ages,

Like Vesta's sacred fire,

Shall live the spirit of thy nurse,

The spirit of thy sire."

The Prophecy of Capys is a fitting ending for a collection of poems for such a power empire: a strong poem, full of hope and conquest and the belief of the gods' favour. The early days are gone, the Republic is no more, the Empire has left behind only the scars of its buildings and the legacy of its laws: but Romulus' Eternal City stands on. Even in this little battered collection of poems, she lives on, and she is known everywhere.

"Where through the sand of morning-land

The camel bears the spice;

Where Atlas flings his shadow

Far o'er the western foam,

Shall be great fear on all who hear

The mighty name of Rome."

Tolle lege - take up and read.

Published on June 01, 2011 07:11

No comments have been added yet.