The Ethical Author

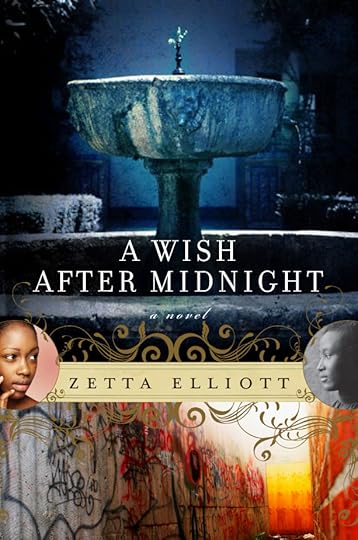

In the summer of 2009 I got an unusual email from Amazon—not an advertisement or order confirmation, but a personal email. This message came from an acquisitions editor who had read my novel, A Wish After Midnight, which I self-published the year before. This editor said he loved the book and wanted to partner with me to help it find a larger audience. After verifying that it wasn't a hoax, I entered into negotiations and ultimately sold the rights to my novel to AmazonEncore, the company's new publishing wing. Wish was given a beautiful new cover and was re-released six months later in early 2010.

In the summer of 2009 I got an unusual email from Amazon—not an advertisement or order confirmation, but a personal email. This message came from an acquisitions editor who had read my novel, A Wish After Midnight, which I self-published the year before. This editor said he loved the book and wanted to partner with me to help it find a larger audience. After verifying that it wasn't a hoax, I entered into negotiations and ultimately sold the rights to my novel to AmazonEncore, the company's new publishing wing. Wish was given a beautiful new cover and was re-released six months later in early 2010.

As a black feminist, I definitely had reservations about partnering with a behemoth like Amazon. I worried what my friends would say—would they accuse me of selling out? Was I betraying my feminist values? Yet, I reasoned, I had spent nearly a decade dealing with rejection from big and small publishers alike. My work was even turned down by a feminist press that was headed by a black woman! I didn't embrace self-publishing at the outset—I was driven to it by the refusal of traditional publishers to give my writing their official stamp of approval. Self-publishing ensured that my work would exist in the world, but I still encountered a great deal of resistance and a certain measure of disdain, and it was a real challenge to get my books into the hands of readers and reviewers.

In the end, to my relief, most of my feminist friends congratulated me on my decision to work with Amazon and did all they could to spread the word about my "new" novel. I had a fantastic experience collaborating with the AmazonEncore team—I was treated with respect, my expertise and ideas were valued, and no changes were made to my feminist narrative about two black teenagers sent back in time to Civil War-era Brooklyn. Wish wasn't reviewed in any major outlets, but the blogosphere embraced it and my overall experience was so positive that I plan to publish my next YA novel with AmazonEncore in 2012.

I'm still determined, however, to keep all options on the table when it comes to publishing. The industry is in flux right now, and I think authors need to respond by being flexible and open to new possibilities. We also need to be conscious of the ways that certain voices continue to be marginalized within the publishing community. Statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children's Book Center demonstrate that authors of color constitute only 5% of the five thousand books published annually for young readers. Getting published is an uphill battle for most writers, but the institutional racism that pervades all sectors of US society makes it that much harder for people of color to have their stories published by traditional houses. Self-publishing has been an important option for black writers for centuries, and I suspect that won't change any time soon.

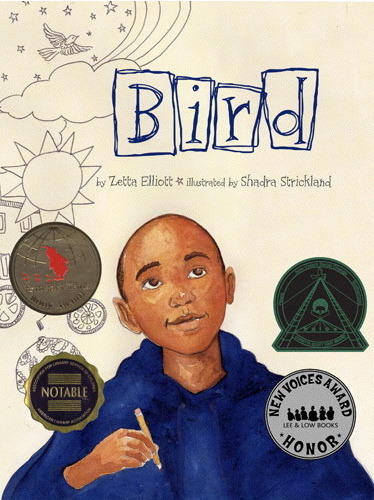

The first time I spoke publicly about self-publishing was at Rutgers University. After reviewing my award-winning picture book, Bird, Dr. Yana Rodgers invited me to speak to her students in the Women and Gender Studies Department. She assigned my self-published play, Mother Load, and I developed a presentation that paid tribute to Barbara Smith and Audre Lorde. I talked about Second Wave black feminist publications and the historical importance of Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, founded by Smith following a 1980 phone conversation in which Lorde asserted, "We really need to do something about publishing." Nearly a decade later, Smith reflected on this pivotal moment:

The first time I spoke publicly about self-publishing was at Rutgers University. After reviewing my award-winning picture book, Bird, Dr. Yana Rodgers invited me to speak to her students in the Women and Gender Studies Department. She assigned my self-published play, Mother Load, and I developed a presentation that paid tribute to Barbara Smith and Audre Lorde. I talked about Second Wave black feminist publications and the historical importance of Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, founded by Smith following a 1980 phone conversation in which Lorde asserted, "We really need to do something about publishing." Nearly a decade later, Smith reflected on this pivotal moment:

Why were we so strongly motivated to attempt the impossible? An early slogan of the women in print movement was "freedom of the press belongs to those who own the press." This is even truer for multiply disenfranchised women of color, who have minimal access to power, including the power of media, except what we wrest from an unwilling system. On the most basic level, Kitchen Table Press began because of our need for autonomy, our need to determine independently both the content and the conditions of our work and to control the words and images that were produced about us. As feminist and lesbian of color writers, we knew that we had no options for getting published except at the mercy or whim of others—in either commercial or alternative publishing, since both are white dominated.[i]

To the students at Rutgers I explained my decision to start my own imprint, Rosetta Press, with its mission to publish books "that reveal, explore, and foster a black feminist vision of the world." I didn't then see any significant difference between my self-publishing project and the aims of the feminists at Kitchen Table Press. But over time I had to admit that I hadn't formed a collective, and I wasn't planning to publish anyone's work other than my own—not until I caught up on the backlog of unpublished manuscripts on my hard drive. Self-publishing is, as the term suggests, very self-centered; its appeal lies in the autonomy it provides, but that level of self-reliance is only partly in line with my understanding of feminism. I confess, I don't want to tell anyone else how or what to write, and self-publishing frees me of the need to please anyone other than myself with my writing. But do I owe the world something more than my books?

To the students at Rutgers I explained my decision to start my own imprint, Rosetta Press, with its mission to publish books "that reveal, explore, and foster a black feminist vision of the world." I didn't then see any significant difference between my self-publishing project and the aims of the feminists at Kitchen Table Press. But over time I had to admit that I hadn't formed a collective, and I wasn't planning to publish anyone's work other than my own—not until I caught up on the backlog of unpublished manuscripts on my hard drive. Self-publishing is, as the term suggests, very self-centered; its appeal lies in the autonomy it provides, but that level of self-reliance is only partly in line with my understanding of feminism. I confess, I don't want to tell anyone else how or what to write, and self-publishing frees me of the need to please anyone other than myself with my writing. But do I owe the world something more than my books?

I concluded my presentation that day by reading aloud June Jordan's prophetic words about the "difficult miracle" of being a black writer in the US:

…we have been rejected and we are frequently dismissed as "political" or "topical" or "sloganeering" and "crude" and 'insignificant" because, like Phillis Wheatley, we have persisted for freedom. We will write against South Africa and we will seldom pen a poem about wild geese flying over Prague, or grizzlies at the rain barrel under the dwarf willow trees. We will write, published or not, however we may, like Phillis Wheatley, of the terror and the hungering and the quandaries of our African lives on this North American soil. And as long as we study white literature, as long as we assimilate the English language and its implicit English values, as long as we allude and defer to gods we "neither sought nor knew," as long as we…remain the children of slavery, as long as we do not come of age and attempt, then to speak the truth of our difficult maturity in an alien place, then we will be beloved, and sheltered, and published.

But not otherwise. And yet we persist.

I've written quite extensively about racism in the publishing industry and the risks and rewards of self-publishing. When aspiring authors ask me how to deal with rejection, I tell them to persist: Keep writing. Get your work done so that when the moment arrives, you'll be ready. Study the industry and know what you're up against. You may have to adjust your expectations, and you may find yourself forming unexpected alliances. But don't surrender your voice or your vision. Stay in the game and work with others who are trying to change the rules.

Lately I've been puzzling over how to be an "ethical author" in an industry that only seems to value the bottom line. Can I preserve my autonomy and still serve the communities to which I belong? I think so. Last month the publishing industry convened in NYC for the annual BookExpo America; BEA 2012 would be the perfect opportunity to ask members of the publishing industry to sit down and get serious about equity. My goal now—in between job-hunting, self-publishing a new novel, and finishing the sequel to Wish—is to replicate the UK Publishing Equalities Charter proposed by the Diversity in Publishing Network (DIPNET):

The aim of the UK Publishing Equalities Charter is to help promote equality and diversity across UK publishing and bookselling, by driving forward change and increasing access to opportunities within the industry…

For many years the industry has spoken collectively of the need to make publishing more diverse yet has not embarked on an industry wide initiative to resolve this issue. "What is widely suspected about publishing has proven true: the industry remains an overwhelmingly white profession…"

The same can be said of the publishing industry here in the US and it's about time we did something about it. I'm not ready to start a feminist press, but I can still advocate for equity so that marginalized writers can become more visible in the literary landscape, which never has accurately reflected the composition of this country.

[i] Barbara Smith. "A Press of Our Own, Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press." FRONTIERS, Vol. X, No. 3, 13-15.