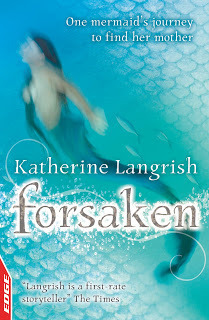

Two exciting things, actually. The first is the lovely cover of the new book I've written. 'Forsaken' will be published in November by Franklin Watts EDGE, and is one of a series, commissioned from several different well-known children's authors (*modest cough*), of quick reads children aged nine and over – children who are competent readers but might feel daunted by a thick, 350 page novel.

This is as sophisticated a story as I've ever written, so I hope some of you adults will like it too. You can fit a lot into a little room.

Last week I was thinking about waterspirits – naiads and undines and kelpies – the denizens of fresh water, rivers, lakes and tarns. But the salt sea has always been the province of mermaids. And rather as fairies were downgraded to flowery little creatures with butterfly wings and sparkly wands, so mermaids – ever since Disney's Ariel, perhaps – have gone sparkly too. Long blonde hair, mirrors and combs: perhaps the accessories don't help – and don't get me wrong, I don't mind this at all, any more than I mind little girls poring over the Flower Fairy books, as my own daughters used to do. Sweet little mermaids are safe and happy reading for little girls. But what about older children?

I'm not even going down the route of the siren, the mermaid as death omen, precursor of shipwrecks. No, where I started from in this little book was the original legend behind Matthew Arnold's classic poem '

The Forsaken Merman'. It's called 'Agnete and the Merman' and I found it in an old book of Scandinavian poetry. In it, as in Arnold's poem, a mortal woman marries a Merman and has seven children by him. One day, as she sits singing under the blue water she 'hears the clocks of England clang' and seeks leave to revisit land and go to church once more.

Once back on shore, however, she refuses to return to the sea. In Arnold's poem, which I really love, the Merman and his children call wildly and vainly for their lost wife and mother from the bay, until at last they accept that she will never return.

But children, at midnight,

When soft the winds blow,

When clear falls the moonlight,

When spring-tides are low:

When sweet airs come seaward

From heaths starr'd with broom,

And high rocks throw mildly

On the blanch'd sands a gloom,

Up the still, glistening beaches,

Up the creeks we will hie,

Over beds of bright seaweed

The ebb-tide leaves dry:

We will gaze, from the sand-hills

At the white, sleeping town,

At the church on the hillside –

And then come back down,

Singing, 'There dwells a loved one,

But cruel is she.

She left lonely for ever

The kings of the sea.There seems to me a great tragic tension in this poem and in the older ballad – the same tension that is found in the Orkney stories of the selkie wife who leaves her fisherman husband to return to the sea. (Which is the same story in reverse, and an important element of my book Troll Mill, the second part of West of the Moon). These stories are about an unbridgeable strangeness between husband and wife, perhaps more specifically the terrible strangeness caused by post-natal depression. They're about seeing someone – even someone as close to you as your partner – as alien. In the Merman story, and with Andersen's story of The Little Mermaid, despite the little mermaid's bargain with the sea-witch – it's not really the physical fact that the mer-people have tails and the humans have legs that causes the trouble. It's the perceived 'fact' that mer-people don't have souls. This will cause the eventual eternal separation of any mer/human marriage anyway; so no wonder the Merman husband, though he calls so desperately, and even climbs on the gravestones in the churchyard to peep through the church windows, will never win his Margaret back.

Then I thought, but what if one of the children went after her mother to try and bring her back? And with that idea, which totally grabbed me, this book just flowed.

And my second Very Exciting Thing is that a new series of Fairytale Reflections will begin on this blog next Friday, and the opening essay will be from the amazing Terri Windling, author of 'The Wood Wife' - which won the Mythopoeic Award for Novel of the Year in 1996 - and fantasy editor extraordinaire.

I'm posting a little early this week, as I'm going away for a few days. Have a good weekend, everyone!

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

I can't wait to read this.

I can't wait to read this.