My smallpox friend remembered

When I visited one of the last surviving smallpox viruses — in Atlanta almost exactly twenty years ago — it had its own name.

When I visited one of the last surviving smallpox viruses — in Atlanta almost exactly twenty years ago — it had its own name.

It was called Harvey.

I was there because this final member of a near-extinct species that has lived with mankind for more than a million years was about to be put to death. Harvey and his 100 remaining relatives, including a Mrs King, a Japanese cousin called Yamamoto and a South American known as Garcia, had lived quietly together for the past ten years but time, I was told, was running out on one of the world's highest-security death rows.

There was an "autoclave" chamber ready to carry out man's first deliberate "species-cide". There was no international outrage. Environmentalists were not battering down the computer-controlled doors at the Centers for Disease Control. Greenpeace was not planning a rescue. Smallpox viruses like Harvey had few friends.

But like many on death rows throughout America all these members of the Variola family, one of the most virulent killers in history, are with us still, still awaiting the results of their latest retrial.

Harvey's family was declared extinct in the wild state thirty years ago after an eradication campaign by the World Health Organisation. The few remaining captive specimens were then gathered into two laboratories, in Moscow and in Atlanta, where a final simultaneous roasting was planned to take place in 1993.

Great ceremony was expected when the disease finally joins the dodo. The day was to be presented as a triumph for superpower co-operation and the New World Order. But it never happened.

There are many explanations for this, some political and some scientific.

But, even back in 1991, down where the final deed was to be done, a few doubts seemed to be growing.

On its concrete surface, Atlanta was (and is) a brash modern city where the only direction is forward, where even the trees are sponsored by Coca-Cola and every television seems permanently tuned to hometown CNN. But within the dark red earth blow there lay (and lies) an old Atlanta of fundamentalist Christianity and philosophical scepticism. Perhaps most important, there lay (and lies still) the Atlanta of Uncle Remus and Brer Rabbit, the characters that made the city famous for dreams long before cable television and Coke Classic came along.

Uncle Remus's creator and alter ego, Joel Chandler Harris, an Atlantan journalist, could not see an animal without anthropomorphising it into a children's friend. The handwritten notes for his famous allegorical tales, left behind on his death in 1908, fill a large library store (also paid for with Coca-Cola cash) barely a few hundred yards from the Centers for Disease Control. What, his admirers then asked, would Harris have made of this extermination business?

Uncle Remus's creator and alter ego, Joel Chandler Harris, an Atlantan journalist, could not see an animal without anthropomorphising it into a children's friend. The handwritten notes for his famous allegorical tales, left behind on his death in 1908, fill a large library store (also paid for with Coca-Cola cash) barely a few hundred yards from the Centers for Disease Control. What, his admirers then asked, would Harris have made of this extermination business?

In his stories of battle between the weak and the strong, would he have made us love Brer Pox as well as Brer Fox?

I met Walter Barrow, a Baptist lay preacher in a cream synthetic Panama hat and an enthusiast for the lost world of Uncle Remus. "Smallpox is no good to anyone but to destroy the last one of God's creations why do we need to do that?

What harm is it doing where it is? That is what Mr Harris would have said.

"Hundreds of years ago", Barrow drawled at me, "we thought we had God's will to destroy every wolf or bear we could see. It was up to us. If we could have exterminated them, we would have. Now we do not think that way. Do we know how we will feel about smallpox in the future?"

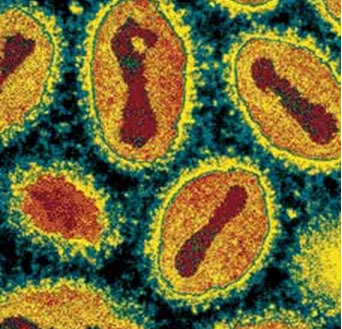

Donald Hopkins, a former scientist at the Atlanta centre, had already written his book in which smallpox is the central character, showing how its distinctive brick-shape viruses, invisible until the invention of the electron microscope, struck Stuarts and Habsburgs, Americans and Aztecs and eliminated 10,000 Bihari Indians in a single month as recently as 1974.

He claimed not to be worried about losing the hero of his history, but was deeply concerned, he said, about man's hubris in destroying the last virus.

"We cannot know the future", he said, "and we cannot justify destroying something that could be of enormous value to us in decades to come, valuable in ways we cannot even conceive of now."

Dr Brian Mahy, who then lead the virologists in Atlanta, was impatient about such objections. Smallpox was for him a rare eradicable evil.

Unlike rival viruses, such as chicken-pox and herpes, Variola does not remain permanently in its victims. That made it unusually vulnerable to new methds of vaccination, containment and elimination in the wild; so man suddenly had the chance to remove its threat entirely.

Mahy recalled his horror 13 years before on learning of the still unexplained infection of Janet Parker, a Birmingham photographer, who was working near a secure smallpox laboratory and became the world's last victim. His ambition was to remove even the possibility of accident or terrorist theft and to transfer his workers to new tasks.

He wanted not only to destroy all the world's smallpox viruses (dismissing suggestions that the devious Soviets might keep a bit back), but to destroy the non-infectious DNA building-blocks of the disease.

He feared that if the DNA were kept for research, some fiendish scientist of the future (possibly the fairly near future) might join it to a harmless relative, such as the smallpox vaccine Vaccinia, to produce a new and dangerous epidemic monster.

The very air in the building encouraged fear: or so it seemed to me. Constantly scrubbed and rescrubbed clean, it passed down into the most dangerous areas through red-coiled lines that hung, like snakes, ready for attachment to sealed plastic suits which the workers wore.

Nobody liked to go beyond the slightest normal procedure. When we entered the inner chamber where the viruses were kept, even the unit manager took one look at the chained-and-padlocked fridge (bound with grey masking tape and unopened for many years) and said he wanted to stay there "as little time as possible, please".

Few journalists had ever been shown it before, Mahy said.

I therefore recorded that apart from the chain-bound fridge, which was silver and blue and would suit a security-conscious serial killer, room 318B contained nothing but a box of Kimberley tissues.

The only excitement planned for the near future was for Garcia, Harvey's South American friend, to be given a brief reprieve from his frozen state, to be warmed up, passed to the care of Janice Knight, a space-suited biologist, and allowed to grow on some monkey cells, bred on a piece of human tissue, before transportation to Moscow.

Mrs Knight and her Russian colleagues hoped that before smallpox was extinguished as a living species, its biological characteristics could be fully mapped by computer. Harvey, named in 1944 after a British nurse who caught the disease from a soldier in Gibraltar, could, for example, be reduced to an 180,000-long list of the nucleotides known to scientists as A,G,C and T.

Smallpox would then be able to be kept in a book instead of a fridge. As long as the correct order of letters had been recorded, the remote possibility of a future Harvey outbreak whether caused by Soviet cheating, an unlucky grave robber, or a neglected African test-tube could be rapidly verified and countered.

I passed on to Mahy some of the worries of Barrow about man playing God with another species. If by some peculiar turn of fate the roles of man and virus were reversed, I asked, how long a list of letters would it take for man's DNA sequence to be recorded?

About 100 million, he guessed. Would that mean that we, too, could be responsibly removed from the world?

Dr Mahy smiled and went back to his world of rationality and white coats.

For Barrow, standing outside Harris's house at "The Sign of the Wren's Nest" it was not much of an answer. "Better not mess with Brer Pox. That's all," he said.

It seems that Mr Barrow won. As I understand it now, writing from faraway London, a decision on the latest trial is awaited shortly.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers