Apocalypse Redux

The following article originally ran in the Wall Street Journal on Saturday, May 14, one week before Judgment Day is to arrive. The following essay is a longer and more detailed version of the story.

May 21, 2011 is the latest in a long line of predictions of the end of the world. What drives doomsayers, both religious and secular?

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

—William Butler Yeats, "The Second Coming"

God…now commandeth all men every where to repent because He has appointed a day in which He will judge the world.

—Acts, 17:30–31

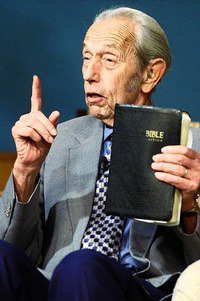

Harold Camping in 2002

That day is Saturday, May 21, says the Oakland, California-based evangelical Christian Family Radio host Harold Camping. By his calculations, May 21, 2011 marks the beginning of end of the world, when Jesus returns to judge us all and rapture those who believe in Him. How did Camping arrive at this date? Genesis 7:4 states that, "Seven days from now I will send rain on the earth for forty days and forty nights, and I will wipe from the face of the earth every living creature I have made." Seven days is actually 7,000 years because in 2 Peter 3:8 it notes that a day is as a thousand years. (Although apparently 40 days is not 40,000 years of rain.) The Noachian flood unleashed its rain of terror in 4990 B.C., so if you add 7,000 years minus 1 (because there was no year zero), you arrive at 2011. Camping claims that May 21 is the 17th day of the 2nd month of the Hebrew calendar, from which the biblical chronology of the flood is determined. Therefore, May 21 is the Big Day.

If you are still around on May 22, it means you are not one of the chosen. But there still may be time to repent before October 21, when the physical end of the world comes. What will happen when that prophecy also fails? (Camping previously predicted September 6, 1994 as Judgment Day.) Doomsayers are nothing if not resourceful. (I mean this in both senses—according to GuideStar.org, which monitors nonprofit assets, Camping's organization is worth over $100 million, raking in a cool $18 million in 2009). Not only do they not admit when they are wrong, they become even more adamant about the verisimilitude of their beliefs, spin-doctoring the nonevent into a successful prophecy, with such rationalizations as these previously employed gems:

Miscalculation of the date.

The date was a loose prediction, not a specific prophecy.

The date was more of a warning than a prophecy.

God changed his mind in response to members' prayers.

The prophecy was just a test of members' faith.

The prophecy was fulfilled physically, but not as expected.

The prophecy was fulfilled spiritually, but not recognized.

Thus it is that Jesus' first-century prophecy (in Matthew 16:28) that, "There shall be some standing here, which shall not taste of death, till they see the Son of man coming in his kingdom," did not attenuate in the least belief in the Second Coming for the past two millennia. Hundreds of predictions have been made, with the Jehovah's Witnesses possibly holding the record for the most failed dates of doom: 1874, 1878, 1881, 1910, 1914, 1918, 1920, 1925, and others up to 1975.

The classic case study in end-times psychology is the 1843 "Great Disappointment" that unfolded after William Miller became "fully convinced that sometime between March 21st, 1843, and March 21st, 1844…Christ will come and bring all his saints with him." When March 21, 1844 came and went without note, the temporary great disappointment was followed by a recalcitrant recalculating of a new date, which was the "tenth day of the seventh month of the Jewish sacred year," October 22, 1844. When the new date passed without note, one disciple announced that "our fondest hopes and expectations were blasted, and such a spirit of weeping came over us as I never experienced before. We wept and wept until the day dawned." That disciple was Hiram Edson who, after concluding that Miller had misread the Book of Daniel, determined that the Sabbath should be observed on Saturday, the seventh and last day of the Jewish week, and he went on to become a leader of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church.

But religionists hold no monopoly on the apocalypse. There are also secular end of days, from Karl Marx's end of capitalism and Francis Fukuyama's end of history, to natural and man-made doomsdays brought about by overpopulation, pollution, nuclear winter, genetically engineered viruses, Y2K, solar flares, rogue planets, black holes, cosmic collisions, polar shifts, super volcanoes, resource depletion, runaway nanotechnology, and most notably, global warming. In his book Our Final Hour, the British Astronomer Royal Sir Martin Rees put our chances of surviving the 21st century at 50 percent. Last year Stephen Hawking famously warned humanity that contact with aliens could result in our enslavement or extinction.

In all of these apocalyptic prophecies—religious and secular—there is a sense of both fear and hope, and herein lies a clue to their appeal. For most true believers the end of the world is actually a transition to a new beginning and a better life to come. For religionists, God destroys Satan and sinners and resurrects the virtuous. For secularists, good triumphs over evil in myriad ways depending on one's doomsday preferences. Radical feminists have prophesized a day when patriarchy will collapse and men and women will live in egalitarian harmony. Marxists projected communism as the liberating climax of a six-stage evolutionary process that requires the collapse of capitalism. Liberal democrats proclaimed the end of history when the Cold War was won by democracy and liberty. And most recently, the Tea Party's messiah is John Galt, the hero of Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged, who leads a strike by the men of the mind, forcing civilization to collapse into anarchy, out of the ashes from which the heroes resurrect an "Atlantis" on earth. In the book's final apocalyptic scene the heroine Dagny Taggart turns to Galt and pronounces "It's the end." He corrects her: "It's the beginning."

Whatever the circumstance or setting, it plays out the same: destruction is followed by redemption. Why? What is the underlying psychology of the apocalypse? In my new book The Believing Brain (Times Books), to be published next week should the world continue its existence, I present my thesis that we form our beliefs for a variety of subjective, emotional, and psychological reasons in the context of environments created by family, friends, colleagues, and culture; after forming our beliefs we then defend, justify, and rationalize them with a host of intellectual reasons and rational explanations. Beliefs come first, explanations for beliefs follow. The brain is a belief engine. From sensory data flowing in through the senses the brain naturally begins to look for and find patterns, and then infuses those patterns with meaning. I call this first process patternicity, or the tendency to find meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless data, and the second process I describe as agenticity, or the tendency to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency. Once our brains connect the dots of our world into meaningful patterns of belief, we look for and find confirming evidence to support them and employ a host of cognitive biases that insure we are always right.

In this belief model, the apocalypse is a pattern of chronology based on our cognitive percepts of passing time from past to future, with a fleeting moment (about three seconds) of a present in between. Our brains are wired to denote patterns of time from beginning to end, and then infuse those patterns with agency and intention, be it God settling moral scores or nature knocking us off our pedestal of human hubris. As well as making things right, apocalyptic visions also help us make sense of an often seemingly senseless world. The literal meaning of apocalypse is "unveiling," or "revelation," from St. John the Divine's narrative in the book of Revelation to any number of the secular chronologies that fit the events of history into a larger cosmic design. How much easier it is to suffer the slings and arrows of life when you believe that it is all a part of a deeper, unfolding plan, whether determined by God or nature. We may feel like flotsam and jetsam on the vast rivers of history, but when the currents are directed toward a final destination it elevates the meaning of our place in it.

In the face of confusion and annihilation we need restitution and reassurance. We want to feel that no matter how chaotic, oppressive, or evil the world is, all will be made right in the end. The apocalypse as history's end is made acceptable with the belief that there will be a new beginning.

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers