Brown & Caletti: NYT Book Review Misses the Point (Again)

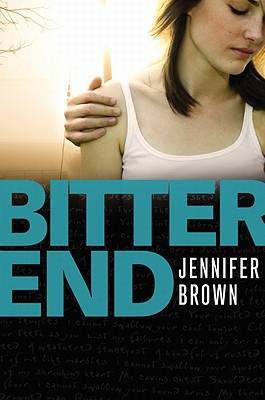

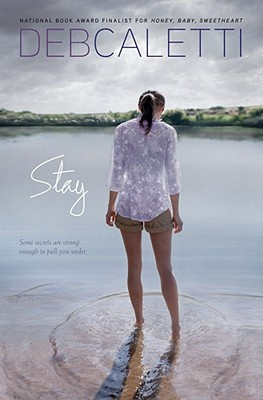

This weekend's Sunday Book Review featured two of my favorite YA authors: Jennifer Brown and her new release, BITTER END, and Deb Caletti and her latest, STAY. Both novels deal with abusive relationships—a brutally tough subject to tackle in fiction, especially in fiction for teens.

This weekend's Sunday Book Review featured two of my favorite YA authors: Jennifer Brown and her new release, BITTER END, and Deb Caletti and her latest, STAY. Both novels deal with abusive relationships—a brutally tough subject to tackle in fiction, especially in fiction for teens.

Stories like Brown's and Caletti's are important, and I'm thrilled to see the books covered by the New York Times. But the article, Novels About Abusive Relationships by Lisa Belkin, goes off the rails right in opening line:

The purpose of young adult literature is often twofold: to tell a story, and to send a message, usually in the form of a much-needed lesson.

Cringing yet?

This broad categorization of YA as Establisher of Morals and Teacher of Wayward Youth (there should totally be a cape and a catchphrase, right?) is as outmoded as my Sony Walkman (no offense to those of you still rockin' cassettes, but…). As soon as I read that opening line, I knew Belkin would miss the point of Brown and Caletti's books and any YA titles she chooses to review.

This broad categorization of YA as Establisher of Morals and Teacher of Wayward Youth (there should totally be a cape and a catchphrase, right?) is as outmoded as my Sony Walkman (no offense to those of you still rockin' cassettes, but…). As soon as I read that opening line, I knew Belkin would miss the point of Brown and Caletti's books and any YA titles she chooses to review.

Why?

She just doesn't get it.

Like I tell my students in our YA novel workshop, the purpose of young adult fiction is singular: to tell a story. Period. Learning lessons and adjusting moral compasses might be an outcome of the reading, but that's entirely up to the reader. If it's going to happen it all, it will happen organically as she's experiencing the journey of the story along with the characters. Of course authors should care about their subject matter, and should always write with something important to say. Call that an underlying message of you'd like, but much as the "do as I say, not as I do" lectures from parents, the moment a novel is crafted with the specific intent to send messages or teach lessons, the audience tunes out.

Belkin assumes:

When today's parents were themselves young adults, they were reading books about adolescents but written for grown-ups ("The Bell Jar," "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings," "Go Ask Alice"). The books their children are reading, though, don't even pretend to appeal to grown-ups — which is, of course, part of their appeal.

This is just another example of a grown-up—one who doesn't understand or like YA fiction—dismissing the entire category as trite, unimportant, non-literature (*cough* Julie Just and the Parent Problem, anyone? *cough*). Belkin misses the mark here, too. YA doesn't have to pretend—lots of it does appeal to grown-ups. It's one of the reasons the category turns a profit year after year despite all the gloom-and-doom news from the publishing industry: teens aren't the only ones buying up (and devouring) those books.

Belkin wraps it up with these thoughts about BITTER END and STAY:

Moreover, the need to tell a good story gets in the way of the message… Any girl who needs guidance navigating a threatening relationship will probably not find it here. But this assumes teenagers are more interested in morals than in sex and drama…

The need to tell a good story trumps all else in fiction. And in music, art, dance, photography, poetry, and arguably any creative expression. We create to share stories and make real human connections to universal truths and experiences, not to teach finger-wagging lessons. Sex and drama? Yes, please. More, please. That's part of real life. Ask a teen if she's interested in reading morals and lessons or real life stuff, what do you think she'll say?

(Hint: If you're still pondering the answer, you might want to reacquaint yourself with teen culture by snagging a few YA books on tape for your Sony Walkman.)

When it comes girls who need help navigating an abusive relationship—or sex, sexuality, parental divorce, grief and loss, peer pressure, drugs and alcohol, mental illness, eating disorders, falling in love, friend betrayals, or any number of real life challenges teens face every day—I encourage Ms. Belkin to resist the urge to assume she knows where they'll find guidance. Like any novel—YA, adult, or otherwise—STAY and BITTER END won't be right for every reader. Some won't like the characters, or they won't connect to the story, or the writing styles won't appeal to their individual palettes. But one of those stories might be the very thing someone reads before she finally understands she's not alone. It might help her deal with her issues and get out of danger.

It might save her life.

That's why it kills me when adults who don't even try to understand YA so casually dismiss these stories, blaming their own inability to relate to, connect with, and appreciate the narrative not on personal reader taste or issues with the construction of the story, but on so-called "pitfalls of the genre."

Pitfalls of the genre? More like pitfalls of adulthood, particularly when adults don't remember what it's like to be a teen. I'm all for debate and critical reviews, especially when those reviews are thoughtful and engaging. What I'm not for is unilaterally dismissing YA novels based on ridiculous and outdated expectations of what young adult literature is supposed to be or do. Every novel is unique, and each deserves to be read and reviewed for its individual storytelling merit, not for its ability to spin the "proper" cautionary tale.

Filed under: books, reading