Chuck Heindrichs – Battery Commander – Part Three

Reefer Madness

As the convoy returned late that afternoon from Phan Thiet, the wiry old First Sergeant pulled me aside and made this recommendation: Halt the convoy just outside the east gate and have an inspection of the returning vehicles and look for marijuana. So, that’s what I did. The troops got off the trucks, flung their flack vests back on the trucks, and they waited. I was absolutely amazed at how much marijuana we collected – I mean grocery bags of the stuff. Lots of it was in the flack vests, but because the vests were piled in the trucks you couldn’t associate any of it with a particular soldier.

Now here’s where a young and naïve Captain comes into play. We collected all the stuff and placed it into a really impressive pile, maybe three feet high. I had the battery formed up and indicated that I would not tolerate drugs on the base. With the entire battery watching I poured diesel fuel on the pile and burned it all. Little did I realize how hated this made me, by not only confiscating the drugs, but then rubbing it in publically in front of everyone.

Then one day I discovered another avenue for drugs coming into the battery, at least to the Quad-50 crews. When a soldier left the firebase I often sent one of our better sergeants to escort him all the way to Cam Ranh Bay. The rationale was that some of these kids would tell you how the drugs were coming onto the firebase. The sergeant would stay with the kid until he had his boarding pass and was walking through the gate toward the airplane. All this to reassure the kid he was safe from retribution, and to keep him from telling his secrets to any incoming new guys. From one of these trips we learned that the marijuana was arriving in specially marked 50 caliber ammo boxes.

I used to complement the Quad-50 crews all the time that when their ammunition came in they were johnnie-on-the-spot getting it from the landing pad. Within ten minutes of the Chinook dropping their ammo they were there; you never had to prod those guys to get their ammo off the landing pad. The next time a load of 50 caliber ammo came in I went with the First Sergeant out to the landing pad and here comes the crew to get their ammo. I said, “Guys wait a minute. We got a telex that there is a suspended lot of ammunition and we need to pull that lot and not let it get into the system.” That was not uncommon to get a telex suspending a particular ammunition lot. I saw a few marked ammo cans, but took all eight of them.

Well the word spread that I had figured it out, when I didn’t figure anything out – one of their own had squealed on the way home. Four days after I confiscated the ammo boxes with the marijuana I woke up in a cloud of smoke. Someone had rolled a smoke grenade under my bed. I remember the next day bringing in the commander of the 4/60th and I think he replaced all of the crews, because it would have become a dangerous situation. At that time in Vietnam fragging of officers was not uncommon.

I was also dumbfounded to learn that a popular way to get drugs on base from Phan Thiet was to remove the return spring from the M-16 and come back with the stuff in the vacated chamber. Not a good idea if you had to use your weapon.

I found these few avenues of what must have been a hundred ways marijuana came onto the firebase. It was a loosing battle, but as battery commander I did what I could.

Vietnamese Platoon

Before I even arrived at Sherry the battalion commander said to me, “When you get out there you are going to see that you also have a Vietnamese infantry platoon. Your job is to get them out of there.” They were in their own sandbag bunkers between the outer and inner wires at the north end of the battery. I knew there were problems between the Vietnamese and the Americans having to do with sex. The Vietnamese had their wives and families with them. There was a little bit of hanky-panky going on, as one would suspect. They were more of a problem than if they were not there. Without them we were well capable of defending ourselves.

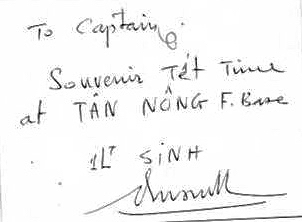

I remember I wasn’t there but a couple of weeks that the Dai Wi, the Vietnamese platoon leader, invited me to a TET celebration with his family (TET 70 was on Feb 5). I remember going over there for the celebration, being polite, and his wife bringing out all this food. I had no idea what I was eating, but I had this huge bottle of Coke to wash it all down. That may have been a mistake, because they thought I loved it and kept bringing it out. The Dai Wi was very gracious and gave me a souvenir picture with a nice message on the back.

Capt. Heindrichs at the TET banquet

Capt. Heindrichs at the TET banquet

I have a vague memory I told them they had to leave, but I don’t remember how I did it. We had been working with the sector commander, and it was out of my hands other than my mission to do everything I could to make sure that we did not have incidents of American GIs having sexual relations with the Vietnamese women coming on and off the base, and that I wasn’t to be the most helpful guy in the world.

A Rule With A Reason

Just a couple weeks after my TET celebration dinner we lost a Quad-50 crewman in a mortar attack. The Duster and Quad-50 guys used to sit on top of their tracks in the evening and at night. We had a rule that after 6:30 PM you wore a flack vest and you wore a helmet. This kid was not wearing his flack jacket or helmet and a piece of shrapnel went into his head just behind his ear, and it killed him.

E-4 Charles Cordle was killed on February 17, 1970, one month after Captain Heindrichs arrived at Sherry.

Two nights later I am walking by this same Quad-50 and I look up and there’s a new guy and he’s not wearing his helmet. I’m thinking, this is not just a harp-on, you’re sitting right where a guy was killed two nights ago. I pull this kid down and try to get him to understand that this is not a rule put in for no reason.

Problem Solved, Or Just Delayed?

On a convoy going into Phan Thiet the supply sergeant said to me, “Hey, you see those grey barrels over there with that orange ring around them? That would solve all of our grass problems.” We were always getting chewed out by our superiors for having too much grass growing in the wire during the rainy season. We took that stuff in the grey barrels and put it into a large tank with a spray spigot, then drove it around the perimeter spraying the vegetation. In a little while we had a desert around the firebase.

The Brown Band Around Sherry

The Brown Band Around Sherry

We used to have generals come from miles around and bring their commands to the base for lunch. Six out of my seven months at Sherry we had the award for the best mess in that part of Vietnam. The generals would walk out on the berm and say to their staff, “This is how I want our bases to look.” Of course it was Agent Orange that did it. None of us knew what it was at the time, just that it was good for killing weeds. Guys on the back of the truck would be standing in that stuff, and I’ve always wondered if anyone ever suffered because of that.

The military sprayed twenty million gallons of Agent Orange during the Vietnam war, covering twelve percent of South Vietnam, and in concentrations averaging thirteen times the recommended application rate for use in the U.S. A number of B Battery soldiers would suffer a variety of illnesses in later life from exposure to Agent Orange.