The Scope of the Slithery Problem

One of the great riddles of epidemiology is the toll of snakebites on India. Various studies over the years have estimated the annual death toll anywhere from 1,300 to 50,000. Until recently, the most convincing analysis out there, based on data from local hospitals, put the number of fatalities at roughly 11,000 per year. But a new study, employing data culled from so-called verbal autopsies, concludes that the problem is much worse than feared:

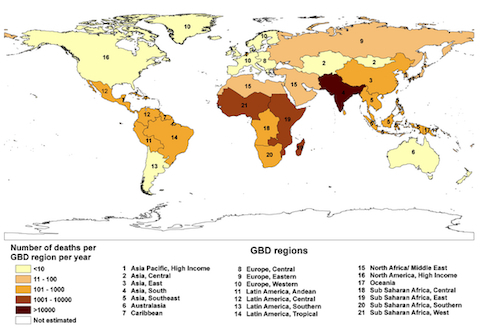

Snakebite remains an important cause of accidental death in modern India, and its public health importance has been systematically underestimated. The estimated total of 45,900 (95% CI 40,900–50,900) national snakebite deaths in 2005 constitutes about 5% of all injury deaths and nearly 0.5% of all deaths in India. It is more than 30-fold higher than the number declared from official hospital returns. The underreporting of snake bite deaths has a number of possible causes. Most importantly, it is well known that many patients are treated and die outside health facilities – especially in rural areas. Thus rural diseases, be they acute fever deaths from malaria and other infections or bites from snakes or mammals (rabies), are underestimated by routine hospital data. Moreover, even hospital deaths may be missed or not reported as official government returns vary in their reliability, as shown from a study of snakebites in Sri Lanka. The true burden of mortality from snakebite revealed by our study is similar in magnitude to that of some higher profile infectious diseases; for example, there is one snakebite death for every two AIDS deaths in India.

Virtually every death by snakebite is preventable, of course, as long as the victim receives the appropriate anti-venom drug in time. It would seem that it would be relatively cheap to disseminate the most popular remedies to far-flung villages, so that victims who are located a great distance from hospitals can be treated as quickly as possible. But as previously discussed on Microkhan, antivenins are absurdly expensive, since so few drug companies produce them in any quantity. Until now, governments and NGOs haven't seen fit to apply pressure on such companies to ramp up production. Now that they have good evidence that a vast market awaits in India, perhaps it's time to state the case for antivenin manufacturing more forcefully. There is money to be made here if a program is created on the national level—and, more important, tens of thousands of lives to be saved.