The Friendly Viruses, and how they can help with the looming antimicrobial resistance crisis

In these days of Zika, Chikungunya, Dengue, and Ebola pandemics, and with the devastating smallpox, influenza, and polio epidemics of the 20th century still fresh in our collective memories, it seems counterintuitive to consider the possibility that viruses will ever be regarded other than with fear and loathing. However, if trials currently underway in Europe, Australia, and the US prove successful, then we may eventually reach a point where certain viruses are viewed with approval and even a degree of affection.

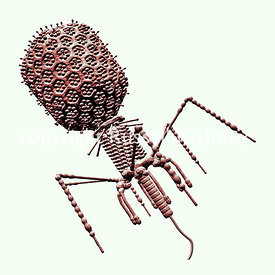

The viruses in question are bacteriophages (“phages”), a class of viruses that have evolved over three billion years as the natural predators of bacteria (hence the name phage = eat), operating as a kind of feedback system to control global bacterial numbers. We now know that phages are the most common biological entities on earth, outnumbering bacteria at least 10-100 fold, with an estimated total of 10 31 (think the number of stars in the sky!).

Phages were independently discovered by Frederick Twort (1915) and Felix d’Herelle (1917), but it was d’Herelle, a brilliant, self-taught French-Canadian who developed the field, naming the viruses, describing their life-cycle, and first applying them as powerful antibacterial agents in 1919, some 20 years before the discovery of the first antibiotics. All this without even seeing the individual bacteriophages, which were too small to be seen by the best light microscopes of the time.

They are split broadly into two types, lysogenic and lytic. Lytic phages are highly effective antibacterial agents that attach to and destroy their bacterial targets, and in the process replicate 50-200 times in roughly 15 minutes. In other words here we have a self-amplifying antibacterial which can increase its concentration (number) by a factor of two billion in just over two hours. Such agents should have huge potential in the post-antibiotic era. By selecting the right phages, those which are exclusively lytic, it is relatively straightforward to devise phage therapies that are very effective against pathogenic bacteria.

The fact is that we’re fast running out of antibiotics. It’s estimated that by 2050 antimicrobial resistance (AMR) will kill 10 million/year. Cancer kills 8 million/year. That’s right: this will be a bigger problem than cancer.

Two infective problems that are still with us, yet amenable to phage therapy, are typhoid fever and blood infection – bacteremia – with Staphylococcus aureus (SAB). Typhoid fever was much feared – it killed Abraham Lincoln’s son and Teddy Roosevelt’s mother- and it remains a scourge, with a global annual death toll of about 160,000. A highly effective phage therapy was developed by a group of doctors in Los Angeles in the 1940s. They intravenously (IV) infused phages against typhoid. Phages kill their target bacteria in a matter of minutes, and so too their patients often displayed what they described as a “truly startling bacteriologic and clinical recovery.” With just a little determination on the part of governments, this technology could readily be re-introduced.

The problem of SAB remains very serious, and is becoming more so with the immense ability of SAB to evade antibiotics. The 30-day death rate of SAB is around 20 -40%, yet there are many reports from the 1920s and 30s, from France and the US, of IV use of phages successfully treating SAB.

Image credit: Bacteriophage T4 Monochrome Shaded on White Sanguine by Russell Kightley, via Russell Kightley Premium Scientific Pictures. Used with permission.

Image credit: Bacteriophage T4 Monochrome Shaded on White Sanguine by Russell Kightley, via Russell Kightley Premium Scientific Pictures. Used with permission.In answer to the obvious question, phages are extremely safe. They only infect their target bacteria, so for example S. aureus phages only infect S. aureus. They are safer than antibiotics, which are now understood to cause collateral damage to our microbiomes. And our bodies are already awash with phages: the gut is full of them, and phages are the most common biological entities in our bodies. In contrast, some antibiotics, such as gentamycin, are highly toxic and demand extreme care in dosing. Clearly phage therapy needs to be revived on a large scale.

What can be done about the looming AMR threat? The first need is for serious money to be spent on the problem, and not just on phage therapy. There have been policy statements and hand-wringing from the highest levels, such as The White House and 10 Downing Street, but there’s precious little new money. New funds should be directed at research directly targeting the looming AMR threat.

Second, serious money should be earmarked for clinical trials. A critical bottleneck is in getting promising antimicrobial approaches – such as phages — into clinical trials. Big pharma doesn’t like taking risks, and these companies won’t invest in a new approach until it’s clinically proven to work. The high cost of clinical trials is often beyond the resources of start-ups.

Third, governments need to get serious about a whole range of other ways to better deal with the bad bugs. These could include strong support for antibiotic stewardship (using our current antibiotics more carefully, although this might only buy time), banning antibiotic use as growth promoters in agriculture, and better educating healthcare workers on hand-washing. Cancer is rightly attacked on many fronts. Governments and society spend large amounts on cancer research, and there are many charities aiming to help fund research into particular cancers, such as breast cancer, or cancers of children. We need to work just as hard if we are to stop antimicrobial resistance overtaking cancer as a global cause of death.

Featured image credit: Bacteriophage T4 Virus Group #2 by Russell Kightley, via Russell Kightley Premium Scientific Pictures. Used with permission.

The post The Friendly Viruses, and how they can help with the looming antimicrobial resistance crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers