Too clever by half

The British have a phrase “Too clever by half”, It needs to go global, especially among hackers. It can have any of several closely related meanings: the one I mean to focus on here has to do with overconfidence in one’s intelligence or skill, and the particular bad consequences that can have. It’s related to Nassim Taleb’s concept of a “fragilista”.

This came up recently when I posted about building a new mailserver out of a packaged fanless mini-ITX system. My stated goal was to reduce my mailserver’s power dissipation in order to (eventually) collect a net savings on my utility bill.

Certain of my commenters immediately crapped all over this idea, describing it as overkill and insisting that I ought to be using something with even lower power draw; the popular suggestion was a Raspberry Pi. It was when I objected to the absence of a battery-backed-up RTC (real-time clock) on the Pi that the real fun started.

The pro-Pi people airily dismissed this objection. One observed that you can get an RTC hat for the Pi. Some others waxed sarcastic about the maintainer of GPSD and the NTPsec tech lead not trusting his own software; a GPS to supply time, or NTP to take time corrections over the net, should (they claim) be a perfectly adequate substitute for an RTC.

And so they would be…under optimal conditions, with everything working perfectly, and a software bridge that hasn’t been written yet. Best case would be that your GPS hat has a solid satellite lock when you boot and sets the system clock within the first second. Only, oops, GPSD as it is doesn’t actually have the capability to set the stem clock directly. It has to go through ntpd or chrony.

So now you have to have a time service daemon installed, properly configured, and running for the timestamps on your system logs to look sane. Well, unless your GPS doesn’t have sat lock. Or you’re booting without a network connection for diagnostic or fault isolation reasons. Now your cleverness has gotten you nowhere; your machine could believe it’s near 0 in the Unix epoch (Midnight, January 1st 1970) for an arbitrary amount of time.

Why is this a problem? One very mundane reason is that logfile analyzers don’t necessarily deal well with large jumps in the system clock, like the one that will happen when the system time finally gets set; if you have to troubleshoot boot-time behavior later. Another is cron jobs firing inappropriately. Yet another is that the implementations for various network protocols can get confused by large time skew, even if they’re formally supposed to be able to handle it.

And I left out the fact that outright setting the system clock isn’t normal behavior for an NTP daemon, either. What it’s actually designed to do is collect small amounts of drift by speeding up or slowing down the clock until system time matches NTP time. And why is it designed to do this? If you guessed “because too many applications get upset by jumping time” you get a prize.

You can certainly tell an NTP daemon to set time rather than skewing the clock rate. But you do have to tell it to do that. This is a configuration knob that can be gotten wrong.

Are we perhaps beginning to see the problem here?

Engineering is tradeoffs. When you optimize for one figure of merit (like low cost) you are likely to end up pessimizing another, like proliferating possible failure modes. This is especially likely if an economy measure like leaving out an RTC requires interlocking compensations like having a GPS hat and configuring your time-service daemon exactly right.

The “too clever by half” mindset often wants to optimize demonstrating its own cleverness. This, of course, is something hackers are particularly prone to. It can be a virtue of sorts when you’re doing exploratory design, but not when you’re engineering a production system. I’m not the first person to point out that if you write code that’s as clever as you can manage, it’s probably too tricky for you to debug.

A particularly dangerous form of too clever by half is when you assume that you are smart enough for your design to head off all failure modes. This is the mindset Nassim Taleb calls “fragilista” – the overconfident planner who proliferates complexity and failure modes and gets blindsided when his fragile construct collides with messy reality.

Now I need to introduce the concept of an incident pit. This is a term invented by scuba divers. It describes a cascade that depends with a small thing going wrong. You try to fix the small thing, but the fix has an unexpected effect that lands you in more trouble. You try to fix that thing, don’t get it quite right, and are in bigger trouble. Now you’re under stress and maybe not thinking clearly. The next mistake is larger… A few iterations of this can kill a diver.

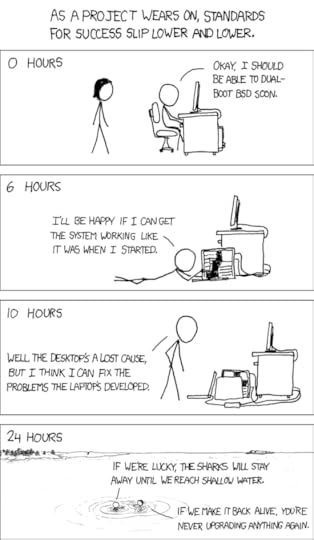

The term “incident pit” has been adopted by paramedics and others who have to make life-critical decisions. A classic XKCD cartoon, “Success”, captures how this applies to hardware and software engineering:

Too clever by half lands you in incident pits.

How do you avoid these? By designing to avoid failure modes. This why “KISS” – Keep It Simple, Stupid” is an engineering maxim. Buy the RTC to foreclose the failure modes of not having one. Choose a small-form-factor system your buddy Phil the expert hardware troubleshooter is already using rather than novel hardware neither of you knows the ins and outs of.

Don’t get cute. Well, not unless your actual objective is to get cute – if I didn’t know that playfulness and deliberately pushing the envelope has its place I’d be a piss-poor hacker. But if you’re trying to bring up a production mailserver, or a production anything, cute is not the goal and you shouldn’t let your ego suck you into trying for the cleverest possible maneuver. That way lie XKCD’s sharks.

Eric S. Raymond's Blog

- Eric S. Raymond's profile

- 141 followers