Read this, not that; or, one children’s book is not as good as another!

Do you know this “eat this, not that” series of books? The idea is to help you make good choices in food and drink to avoid hidden calories that will tank your health.

Well, Rosie had the thought that we could do something similar with books for the Library Project*.

The book we are looking at — and maybe, after all, this is the only book we’ll do this for, but you never know — is The Penderwicks, by Jeanne Birdsall. The Penderwicks is lots of fun and is written well, in that it doesn’t talk down to the child and would keep a reading-aloud parent amused. Many, many people really love it.

The cover is super attractive. It’s no wonder the book is so popular; the cover takes me to those wonderful books of my own childhood that kept me entertained. The charming silhouette of children and animals frolicking on the cover can’t help but draw the reader in. (And it has an award!)

This genre — children on holiday in the country — is a tried-and-true one. Right away The Penderwicks promises to be a favorite, and I wanted to love it.

However, there are many other books with the same theme that are better and don’t contain a certain moral ambiguity. So here I will tell you what I don’t like and then give you suggestions of what to read instead.

At the heart of The Penderwicks is an episode in which the girls’ youngest sibling is left unattended by her sisters and is nearly attacked by a bull, only to be rescued at the last moment. The children make a pact not to tell their father about the danger.

This pact begs to be put to the test. For the rest of this book, one is hoping that the conflict will be resolved. And here is the crux of my objection: in a better book, it would come to light and the children would make a clean breast of their negligence, which was a dereliction that clearly ought to have weighed on their consciences.

In fact, an opportunity arises later in the book for them to say something to their father; but rather than do so, they lie to cover up the event and their culpability. Astonishingly, this lie is not resolved.

The girls also tell another small but unmistakable lie to the unpleasant neighbor/landlady about their dresses, which actually belong to this lady, unbeknownst to her.

An author has a responsibility to moral reality. For a children’s author, this is a sacred duty. The child is being formed to a great extent by the stories he reads, watches, and hears. It’s really important that these stories be completely wholesome!

Lying in particular is intrinsically wrong. You can’t just excuse a lie because of the circumstances! The moral code has always stressed the importance of telling the truth — even in small matters — and children have to be taught that without trust, people can’t relate to each other at all. That this book treats lies, great and small, as easily glossed-over and rather neutral is not acceptable.

There are a couple of other themes that I object to — I do! You can call me picky, but I don’t see the point of exposing 8-12 year-olds (the recommended age group for the book) to any of it.

There is a silly one-way crush of the eldest Penderwick girl on the caretaker’s son. Where in a book from a different era their friendship (for they are friends) would have been handled with appropriate delicacy, in this story it’s really unsatisfactory: the crush kills the friendship, which is exactly the contemporary real-life difficulty that the author should have been able to show an alternative to. Somehow, in older books, children are given a way to handle awkward, premature feelings. It’s almost as if the author doesn’t know what those ways might be, or thinks that in a modern story, a boy-girl crush has to be a feature.

The neighbor herself, Mrs. Tifton, is problematic as a character in a children’s story. I can’t remember a children’s book in which a difficult adult character is left to be either rather misunderstood or with her failings unresolved.

In this case, Birdsall makes a point of introducing the subject of Mrs. Tifton’s divorce and her husband’s abandonment of their son — rather a heavy issue, no matter how common it might be these days. To put such a theme in a book for young children is inadvisable, it seems to me.

Mrs. Tifton ends by marrying her equally obnoxious boyfriend; this is just sad, even for her.

I remember this outcome really bothering Bridget, who felt that the lady and her son (the “boy” of the subtitle) deserved a happy ending, or at least not a dreadful one. For sure, today’s mores are reflected in this plot development: to most people, a remarriage involving two unchanged people is not significant as a moral issue.

Of course, to a child reader — who is trying to understand the world and the choices adults make — it’s very significant and potentially harmful to his sense of whether Providence has in store for everyone a happy (or at least a deserved) ending. Mrs. Tifton is neither that bad character who comes to a bad ending nor a complicated character who finds understanding. She is just a selfish, weak person whom the author manipulates the children into not liking — but also not understanding. This whole plot element ends up having a “young adult lit” vibe that is particularly objectionable to me. It has the air of grooming the reader for further, more “realistic” sorts of stories.

It’s simply a fact that today, most in this age group are reading young adult fiction or desperately wanting to. We need to protect them and give them really innocent, good literature — the “1000 Good Books.” They need challenges but not confusion.

Other books offer the fun of a summer-vacation adventure with good morals and solicitude (or justice) for all the characters. And the children don’t just get into difficulties; they exercise that most important of childhood qualities, pluck, to get out of them.

So instead, read this, not that:

Magic by the Lake, by Edward Eager — Children on holiday navigate tricky magic and must use their wits to stay ahead of it. Their stepfather (their mother is a widow, which you discover in the equally excellent previous books) is doing his best to provide; they end up helping him, which is really sweet.

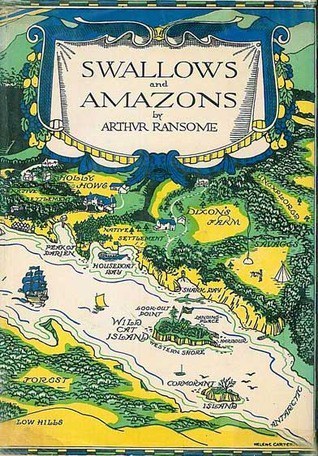

Swallows and Amazons, by Arthur Ransome — Children on holiday have wonderful adventures in a boat and on an island. The adults who, from our own adult point of view, might not have things entirely under control, nevertheless maintain high standards for personal responsibility — standards which the children must live up to in the course of their escapades.

Gone-Away Lake, by Elizabeth Enright — A girl and her boy cousin find an abandoned summer village and make friends with two elderly and odd siblings whom they must learn to understand (and it’s well worth it). They also, like the Penderwick children, try to keep a secret from the adults in charge, but the secret is not a guilty one, and it comes to light for reasons not in their power — but also not unwelcome to them.

The Woodbegoods, by E. Nesbit — (a sequel to The Treasure Seekers) the children try to be good but only cause disaster; since this is the plight of children everywhere and in all times, the story is most fulfilling, amusing, and clever.

The Railway Children, by E. Nesbit — The children are quite sheltered by their mother for the real reason for their exile, which they take to be a summer holiday but which is necessitated by their father’s imprisonment. Yet they are the means of bringing about his vindication. Honor is a particularly important subtext in this story. (The movie is delightful — a really fun family film. I’ve written about E. Nesbit — and this movie — before.)

The Cottage at Bantry Bay, by Hilda van Stockum — The children are poor and the family is loving; they have many adventures, ending with the discovery of a treasure that enables them to procure medical care for their brother.

All of these make great read-alouds. The age level is 8-12 but all ages will enjoy them! (The Amazon links are affiliate links — thank you!):

What are your favorite summer adventure stories?

*What is the Like Mother, Like Daughter Library Project?

The post Read this, not that; or, one children’s book is not as good as another! appeared first on Like Mother Like Daughter.