In His Rising is Our Hope: Art and the Resurrection

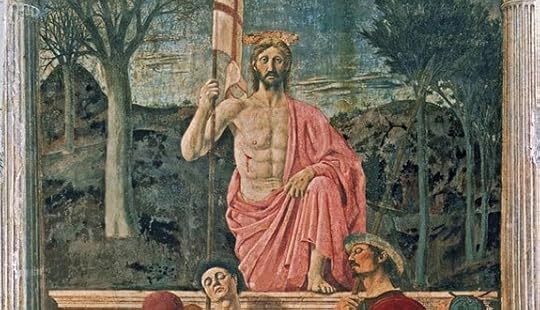

Detail from “Resurrection” (c. 1460) by Piero della Francesca (WikiArt.org)

In His Rising is Our Hope | Sandra Miesel | Catholic World Report

A short history of how Christians throughout the ages have depicted the mysterious and transforming event of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

In him, who rose from the dead,

our hope of resurrection dawned.

The sadness of death gives way

to the bright promise of immortality.

— Preface for Christian Death I

Sacred images do not instantly spring from the pages of Scripture to gauzy forms on gilt-edged holy cards. Traditional Christian art, like Christian theology, developed slowly as the Church’s understanding of the Gospel deepened and the cultures around her shifted. For instance, today’s Catholics probably picture our newly Risen Savior as nude save for a fluttering wrap and carrying a banner blazoned with the cross. Such an image would have shocked ancient Christians. Although well aware that “If Christ has not been raised…faith is futile” (1 Cor 15: 17), they did not try to represent that rising. Artists experimented for centuries to find appropriate ways to depict the climax of Our Lord’s redemptive work.

The Gospels are silent about the exact moment when Jesus was restored to new life. Instead they give four unique accounts of holy women and apostles finding the tomb empty on Easter morning (Mt 28:1-10, Mk 16:1-8, Lk 24:1-12, Jn 20:1-18). Afterwards, the risen Christ appears to his followers with convincing proofs of his identity: his transformed body is still his own body, neither a delusion nor a ghost.

Early Christian artists did not presume to supplement Scripture. Perhaps they feared to invade God’s privacy, as it were. Rather than attempt direct illustration of Our Lord’s emergence from the tomb, they painted catacombs and sculpted tombs with scenes from the Book of Jonah. Jesus himself had used the Sign of Jonah as a veiled prophecy of his death and resurrection (Mt 12:40). As the prophet spent three days inside the whale, so would the Son of Man spend three days buried in the earth.

Another way to avoid the delicate moment when Jesus rose was to replace his figure with his cross-shaped standard that bears a Chi-Rho within a victory wreath. This is planted between the grave guards on Roman sarcophagus carvings of the fourth century. The same tactic was applied to early Crucifixion scenes: a sign takes the place of physical reality.

But Christ’s sepulcher itself became the preferred element in depictions of Easter. The oldest known example of this image was painted about 230 AD on the baptistery wall of a church in the Syrian town of Dura-Europos. Here the three “Myrrh-Bearing Women” bring spices to anoint Jesus (Mk 16:1). They approach a huge, plain sarcophagus, not the hollow rock chamber that the Gospels describe. The empty tomb was an appropriate—and popular—baptismal motif because receiving the sacrament is a spiritual dying and rising with Christ (Rom 6:3-4).

Coincidentally, a mural of Ezekiel’s vision of the dry bones reanimating (Ez 37:1-14) adorned the synagogue in the same town. Christians had inherited the Jewish belief in a general resurrection of the dead at the end of time attested by Mary of Bethany before the raising of her brother Lazarus (Jn 11:24). As a creature of body and soul, mortal man will need both reunited to participate fully in the life of the world to come. Human resurrections, past and future, often complement the Resurrection of Jesus in Christian art.

A century after those murals appeared in Dura-Europos, the Emperor Constantine aligned himself with Christianity and built churches over sacred sites all over the empire. Among these was the Anastasis Rotunda in Jerusalem, begun in 337 AD. Its conical canopy sheltering the tomb of Christ influenced later depictions of the Easter tomb. For instance, it appears on a Roman ivory plaque made circa 420 AD as part of a small box. (Another side of the box has the earliest known Crucifixion scene.) Here one door of the elaborate open tomb depicts the Raising of Lazarus and a mourning woman. As in Mt 28:1, 4, two holy women and two stupefied soldiers flank the tomb.

More elements were added to Resurrection scenes: angels, extra guards, women prostrate before the Risen Lord. Subjects were combined to give a panorama of salvation that collapsed time and space. The Resurrection might be juxtaposed with the Crucifixion or Ascension or other biblical episodes.

Although the holy women at the empty tomb would long remain a popular image, by the end of the seventh century, the Church wanted to show Christ’s own victorious power in action. “Material figurations” were judged especially useful for forming faith in the Savior who was both True God and True Man. This new confidence in theology made visible also permitted artists to picture what preceded the Resurrection—death and entombment.

Thus arose a new visual formula called the Anastasis.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers