FROM THE MANOR TORN

My friend Stephen Mertz is a prolific word slinger who always delivers thrills and solid entertainment in every novel he writes. Like me, his early short stories were published in Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine—so we are brothers under the pen...Here in Steve's own words is the low down and dirty story of his first novel and the evil empire known as Manor Books... FROM THE MANOR TORNSTEPHEN MERTZ Manor Books was a low-end, New York, publishing house in the 1970s, operated by pack of thieving scuzzballs who published my first novel, Some Die Hard, many years ago. Happily, Some Die Hard is now available in a dandy e-book edition. Here, though, is the story of how Manor Books tried to screw me and how I screwed them right back, via long distance no less, without spending a penny.

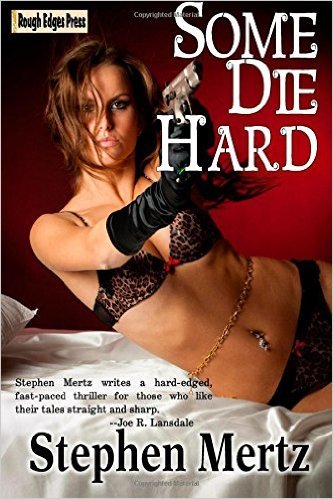

My friend Stephen Mertz is a prolific word slinger who always delivers thrills and solid entertainment in every novel he writes. Like me, his early short stories were published in Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine—so we are brothers under the pen...Here in Steve's own words is the low down and dirty story of his first novel and the evil empire known as Manor Books... FROM THE MANOR TORNSTEPHEN MERTZ Manor Books was a low-end, New York, publishing house in the 1970s, operated by pack of thieving scuzzballs who published my first novel, Some Die Hard, many years ago. Happily, Some Die Hard is now available in a dandy e-book edition. Here, though, is the story of how Manor Books tried to screw me and how I screwed them right back, via long distance no less, without spending a penny.I wrote Some Die Hardin 1975 while I was living in Denver. Private eye Rock Dugan's first and only case. I dedicated the book to my mentor and brother writer, the late Don Pendleton, who was generous and helpful in his critique of the novel in manuscript form.

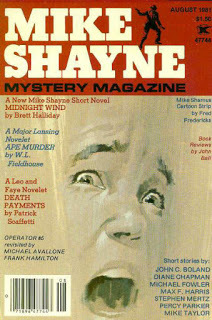

Writing the book was fun. Finding a home for it with a publisher took another four years. During those four years, I sold a handful of stories to Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine while a New York agent circulated Some Die Hardfor publication consideration. It received a polite round of encouraging words, but no acceptance.

Writing the book was fun. Finding a home for it with a publisher took another four years. During those four years, I sold a handful of stories to Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine while a New York agent circulated Some Die Hardfor publication consideration. It received a polite round of encouraging words, but no acceptance. After eventually quitting the agent and leaving Denver for the rural mountain life, I spotted a market report in Writers Digest. A mass market publisher in New York was looking for previously unpublished novelists who lived outside the New York area. The suggestion was the publisher—Manor Books by name—was reaching beyond the literary and pulp cliques of the Northeast, hunting for new talent in the heartland. Hey, that was me!

At the time, I owned a small second hand bookshop in Durango, Colorado—wall to wall unfinished wooden shelves packed with paperbacks. Actually had an entire room devoted to Harlequin romances. Until about five years earlier, Durango was strictly a cowboy and mining town. Then the hippies discovered it. The tourists came next and, by the time I arrived in the 1970s, Durango’s residents grew to include people drawn from everywhere. Writers. Artists. Musicians. Movie people (parts of Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, among other films, were shot in the area). Everyone I hung out with was from somewhere else. We preferred the back roads and the pines and peace and quiet to the city life most of us had left behind. We were young, broke and happy. A bohemian, hedonistic, fun lifestyle. Durango was that kind of place.

At the time, I owned a small second hand bookshop in Durango, Colorado—wall to wall unfinished wooden shelves packed with paperbacks. Actually had an entire room devoted to Harlequin romances. Until about five years earlier, Durango was strictly a cowboy and mining town. Then the hippies discovered it. The tourists came next and, by the time I arrived in the 1970s, Durango’s residents grew to include people drawn from everywhere. Writers. Artists. Musicians. Movie people (parts of Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, among other films, were shot in the area). Everyone I hung out with was from somewhere else. We preferred the back roads and the pines and peace and quiet to the city life most of us had left behind. We were young, broke and happy. A bohemian, hedonistic, fun lifestyle. Durango was that kind of place.So off went Some Die Hard. (The novel’s original title was The Flying Corpse, however it had been suggested a less, uh, spectacular title might stand a better chance of acceptance). Not only did I think Some Die Hard was a serviceable title, but so did writers Marvin H. Albert (under his Nick Quarry pseudonym) and Carroll John Daly—both of whom had used the same title in their day. I snail-mailed Some Die Hard over the transom (unsolicited) to Manor, and it took those slicks all of a New York minute to jump on a guy living way out in the Rockies, without a telephone.

They offered me $750.

Honestly, I was overjoyed. After four years, I felt finally vindicated as a writer. This being my first novel, though, and thinking $750 really wasn’t that much money, I trudged through the snow to a neighbor’s house. I asked to use their phone and called the only three published novelists I knew: Michael Avallone in New Jersey, Don Pendleton in Indiana, and Bill Pronzini in California. The unanimous advice from all three pros was to go for it. Get published. Start building a career—And ask for more money.

So I did, via a collect telephone call. Editor Larry Patterson was the soul of cordiality, promptly boosting the advance up to a thousand dollars without batting an eye. He was probably thinking, What the hell, we’re not going to pay the chump anyway.

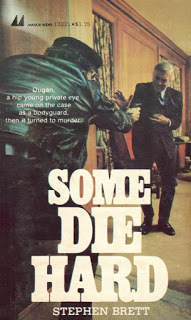

I was aware Manor Books was a bottom line concern, so I decided to use a pseudonym to avoid getting boxed in as a low-rent writer. Hence, the original penname Stephen Brett—the surname being a tribute to Brett Halliday(aka: Davis Dresser), a favorite writer of the private eye stories I’d been reading since high school. Manor moved fast. There was money to be made. Within weeks I had a contract in hand for the astronomical sum of one thousand dollars, payment due upon publication.

ONE THOUSAND DOLLARS!

Dang. Where do I sign? My writing journal indicates I had fifty-four cents to my name the day that contract arrived.

The book was printed and bound (cheaply, with a recycled cover photo from an earlier Manor title, Tether’s End by Margery Allingham) and shipped. It was on sale within months, even in remote little ol’ Durango (the nearest cities being Albuquerque—4 hours away—and Denver—8 hours away). Since local friends were buying my book, supposedly so were readers from coast to coast. The book was reviewed in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. The reviewer thought it was okay.

The book was printed and bound (cheaply, with a recycled cover photo from an earlier Manor title, Tether’s End by Margery Allingham) and shipped. It was on sale within months, even in remote little ol’ Durango (the nearest cities being Albuquerque—4 hours away—and Denver—8 hours away). Since local friends were buying my book, supposedly so were readers from coast to coast. The book was reviewed in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. The reviewer thought it was okay.However, I hadn’t gotten paid. Hmm. Okay. I’ll call Larry. Quoth Larry, “Sorry, Steve. We’re a little backed up, blah, blah, blah. The check will be in the mail by the end of the week.” Great…Except the check wasn’t in the mail, that week or any of the following weeks.

The months dragged on. I still didn’t have a phone. Sometimes I’d pester my neighbor. Other times, if I was in town, I’d used one of the old-fashioned wooden telephone booths then in the lobby of Durango’s Strater Hotel. I’d think of Louis L’Amour, a local celeb of sorts since he had a summer place three miles north of town. It was known L’Amour had written some of his 1950s pulp westerns while staying at the Strater between jobs working in the area as a wrangler for what were then called dude ranches. I wondered if L’Amour ever sat in the same booth in his hungry days, hustling up New York editors for overdue payment. I’ll bet he had. Now it was my turn. I was young and this was part of the adventure.

But the bastards still didn’t send me my check.

I was beginning to understand. In looking for new novelists outside the New York area, what Manor Books was really doing was trolling the boonies for writers who were good enough to be published, but who wouldn’t have the clout or the resources to collect the money owed them. Manor would essentially be taking on books for free and walking away with 100% of the profits—Like I said—thieving scuzzballs.

I was beginning to understand. In looking for new novelists outside the New York area, what Manor Books was really doing was trolling the boonies for writers who were good enough to be published, but who wouldn’t have the clout or the resources to collect the money owed them. Manor would essentially be taking on books for free and walking away with 100% of the profits—Like I said—thieving scuzzballs.Among my customers at the book exchange was a nice guy with whom I’d become friends. His story was he’d been burned out while being a big city lawyer. At the time, he was on a soul search—holed up in a snowy mountain town in the middle of nowhere, honing his skills as a mime. He was an avid reader. And guess what? He still had his license to practice law in the state of New York.

“How’s about this?” I suggested over beer and pizza down at Farquart’s. “You get me that grand the sons of bitches owe me and you can waltz in and out of my shop anytime you want and take home as many books as you want for as long as the shop exists.” His eyes lit up. Some killer instincts do die hard, even in one who’d rather be a mime than a lawyer.

“How’s about this?” I suggested over beer and pizza down at Farquart’s. “You get me that grand the sons of bitches owe me and you can waltz in and out of my shop anytime you want and take home as many books as you want for as long as the shop exists.” His eyes lit up. Some killer instincts do die hard, even in one who’d rather be a mime than a lawyer.He said, “Here’s what we’ll do. Find out if your publisher has done this to anyone else. Then I’ll fire off a registered letter to them on my New York stationary. We’ll threaten to sue for the thousand and for damages. And if they’re doing this to other writers though the mail, we’ll threaten to charge them under Federal law with conspiracy to defraud using the US Postal System.”

Well, all right.

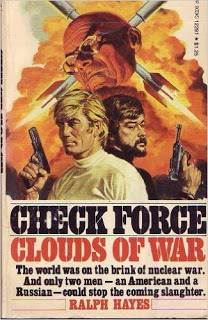

First thing I did was go down to the local book and magazine store (remember those) that was stocked with Manor titles. I wrote down the names of the authors of those books, and then went about searching for their addresses. My primary resource was the library reference work, Contemporary Authors. I made contact with two writers: Ralph Hayes, an active and not bad pulpist living in Florida (Manor had published his Check Force series) and James Holding, the author of a western.

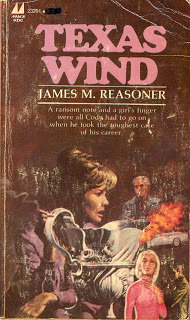

First thing I did was go down to the local book and magazine store (remember those) that was stocked with Manor titles. I wrote down the names of the authors of those books, and then went about searching for their addresses. My primary resource was the library reference work, Contemporary Authors. I made contact with two writers: Ralph Hayes, an active and not bad pulpist living in Florida (Manor had published his Check Force series) and James Holding, the author of a western.Around this time, I received a letter from another new writer, James Reasoner, who’d soldhis first novel to Manor, but was having trouble getting paid and was hearing bad things about them. What did I know? I’d been reading and enjoying James’ stories in Mike Shayne, which by then had become a showcase for the emerging talent of my generation.

The following paragraph from my return letter to James (dated 4/4/80) pretty much captures the situation at that point.

All you have heard about Manor is only too true. They currently owe me a grand and the matter is now in the hands of my attorney. They were supposed to pay on publication and that was eight months ago. The lawyer gave them until April 10. But at least they sent me copies of my book! A guy named Jim Holding (not MWA’s James Holding, but his grandson) didn’t even know his book was out until I spotted it on the stands and wrote him about it. Manor has simply clammed up on him totally to keep from being hassled about on-publication payment. I also exchanged letters with Ralph Hayes. His feeling was Larry Patterson is an okay guy who unfortunately has editorial ambitions outstripping the company’s ability to pay promptly. Ralph’s advice (and my and Jim Holding’s experience bears this out) is to badger Patterson regularly (like every week) via collect phone calls, urging for payment.

All you have heard about Manor is only too true. They currently owe me a grand and the matter is now in the hands of my attorney. They were supposed to pay on publication and that was eight months ago. The lawyer gave them until April 10. But at least they sent me copies of my book! A guy named Jim Holding (not MWA’s James Holding, but his grandson) didn’t even know his book was out until I spotted it on the stands and wrote him about it. Manor has simply clammed up on him totally to keep from being hassled about on-publication payment. I also exchanged letters with Ralph Hayes. His feeling was Larry Patterson is an okay guy who unfortunately has editorial ambitions outstripping the company’s ability to pay promptly. Ralph’s advice (and my and Jim Holding’s experience bears this out) is to badger Patterson regularly (like every week) via collect phone calls, urging for payment.The windup: Upon receipt of the mime’s registered letter, Manor Books promptly mailed me a check for one thousand dollars.

Manor Books closed shop a few years later. Word gets around.

The mime? Every book he took out of the book exchange, he brought back after he’d read it so I could sell it again. So the whole deal didn’t really cost me a penny. I knew good people in Durango in those days.

Everyone got what they deserved, and what more can you ask for? Oh, and Some Die Hard remains—available as an e-book, which might just net me another thousand dollars…

FOR MORE ON SOME DIE HARD CLICK HERE

Published on March 21, 2016 21:35

No comments have been added yet.