Is Theme Important in Nonfiction too?

[This is the seventh post in our series on Theme. Special thanks to Joe Fontenot, who asked the question above.]

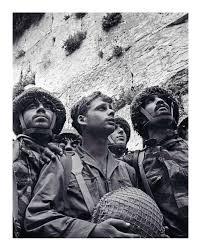

David Rubinger’s iconic photo of Israeli paratroopers at the Western Wall, 7 June 1967.

Answer: Absolutely. Maybe even more so.

Lemme offer an answer based on my own process in structuring and writing The Lion’s Gate.

The Lion’s Gate was published by Sentinel/Penguin in 2014. It’s a narrative nonfiction book about the Arab-Israeli war of 1967—the Six Day War.

Theme was everything in my process, not just in researching and writing the book but also in writing the Book Proposal.

A book proposal is that essential 50-page document that agent and writer (in this case, Shawn and I) submit to deep-pockets publishers, hoping to make a deal with an advance to pay for writing the book.

In other words, theme was critical in this instance not just artistically but financially. It was make-or-break stuff.

Okay …

First, a little historical background so that what follows will make sense:

The Six Day War was a life-and-death clash between Israel and the combined forces of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. It took place between June 5 and June 10, 1967.

The war was initiated by Egypt’s then-president Gamal Abdel Nasser, who in May of that year, in violation of a long-standing UN agreement, began moving tanks (1,000) and troops (100,000) into the Sinai Peninsula, right up to Israel’s southern border. Simultaneously Nasser mounted a fiery rhetorical campaign throughout the Arab world. War was coming, he declared. Its objective was the “elimination of Israel.” Twenty-two Arab nations promised troops, money, and weapons.

Israeli diplomats appealed frantically to their allies—the United States, Britain, and France—for military and political support. Each nation for its own reasons demurred. Israel, outnumbered 40 to 1 by the combined populations of its enemies, appeared to stand at the brink of annihilation. A second Holocaust seemed imminent with the world standing by, doing nothing.

The war began on June 6. Six days later, after furious clashes on three fronts, Israel had destroyed the Egyptian army and air force in their entireties and routed the forces of Jordan and Syria. She had captured the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, and the Old City of Jerusalem.

It was one of the most spectacular David-and-Goliath victories in the history of warfare.

Okay, that’s the historical background. That’s the material and context that I intend to write about.

But what, I’m asking myself, will this book be about?

The answer is not that it’s about the Six Day War.

That’s the subject.

It’s not the theme.

Important: there is no “right answer” to this question. What counts is what theme strikes a chord with the writer. Hundreds of books could be and have been written on the subject of the Six Day War. My question to myself: “What book do I want to write? What theme rings bells for me?”

A book could be written, for instance, whose thrust was, “The Six Day War created the modern Middle East. All the problems we’re facing today came from that war.” (In fact, Michael Oren’s excellent Six Days of War is on exactly that theme.)

Another possible theme could be “The Six Day War produced the rise of Islamism. Nasser’s Arab world was secular. It was only after the defeat in ’67 that Arab nations turned to Islamism as an answer to their problems.”

We could look at the war, from the Israeli side, as a miracle from God. Or as a response to the Holocaust. We could credit Israeli generalship. Or Israeli desperation.

In other words, the number of potential themes on the same subject is limitless.

Again, the question I’m asking myself, long before starting to write, is:

What grabs me about this material? Why has it captured my imagination so powerfully?

I decided that the theme was exile.

Or more precisely, return from exile.

Here was my thinking process:

The iconic image produced by the Six Day War was that of Israeli paratroopers weeping and praying after their capture of the Western Wall. Perhaps you’ve seen the famous David Rubinger photo.

The Western Wall was and is the holiest site of the Jewish people. Jews by tens of thousands make pilgrimages today to visit and pray at this location. The wall itself is the final remnant of Solomon’s temple, which was burnt to the ground by the Romans in 70 A.D. From that date till June 7, 1967 the Jewish people’s most sacred site resided in the hands of others. For nineteen hundred years, no Jew could stand before that wall and say, “This belongs to me. I am free to pray here.”

In other words: exile.

I decided that the theme of my story of the Six Day War would be “return from exile.”

Or, more specifically, “reclaiming the lost soul-center of the people.”

The climax of the story would be the moment the first Israeli paratroopers reached the Western Wall—and their emotional response to this epochal event.

By the way, this statement of theme was central to the book proposal that Shawn, acting as my agent, submitted to Big Five publishers. (The Lion’s Gate, we knew, was too big a book for us to publish at Black Irish.) I was passionate and adamant about this theme of exile. It was the central fixture of the proposal and the primary selling point of the whole project. My pitch was that this theme would be unique, original, and compelling to readers.

Did it work?

Apparently, because a bidding war ensued. In the end, we were able to pay for three years of work.

But let’s get back to Theme from the artistic side. Remember, a few posts ago, we were addressing “levels of theme.” The more levels, we said, the more powerful the theme.

Okay.

We’ve identified the theme of this book we want to write.

What, I’m asking myself now, are the levels of this theme?

Why am I asking this? Because a book or a movie, if it’s going to possess power and emotion, must work on multiple levels. Even if these levels are invisible to the reader or moviegoer, even if they pass right over his or her head, they are still working in the sphere of the unconscious. They give the piece depth and focus and power.

When I’m asking myself, “What are the levels?”, I’m asking, “Does this theme have power? Will this book deliver to the reader a steak-and-potatoes experience?”

Levels of theme.

Let’s start digging.

Level #1, the surface interpretation of the “return from exile/reclaiming the lost soul-center of the people” theme, goes like this:

The Western Wall is literally the soul-center of the Jewish people. Reclaiming it would mean the final and complete end of exile. The children of Israel would, after nearly two millennia of sojourning in the lands of others, finally possess the full measure of nationhood—the ancient territory of Israel and the holiest of its sites. (Before ’67, the Wall was in the hands of the Jordanians and forbidden to Jews.)

That’s Level #1 of the theme.

Let’s dig deeper, reaching for the universal.

Level #2 would take this theme and apply it not just to the Jews but to any people. Putin’s Russia seeking to reconstitute the Soviet sphere by seizing territory in Georgia, Chechnya, the Ukraine. ISIS’s advance into “the caliphate.” The history of Europe from the 16th Century on, including World War I and World War II, is about nothing but the reclaiming by nations of ancient soul-centers.

Let’s go deeper.

Level #3 is that of the individual. You and I. Don’t we too possess a soul-center that we have been in exile from? Our artistic calling that we have never fulfilled? A love we’ve lost? A portion of our manhood or womanhood?

The Gnostics believed that exile was the inherent condition of the human race. Exile from our spiritual center. From our native soul. From the divine.

Let’s go deeper.

Two aspects define the reclaiming of that soul-center, both for a people and for an individual.

First, that soul-center can be reclaimed only by action. Words alone will not produce the personal or people-wide revolution we seek. Nor can that soul-center be given to us by others, however well-intentioned. We have to take it back ourselves, by main force.

Second, the action of reclaiming our soul-center must inevitably be taken in the face of adversity. The dragon will not give up the gold without a fight.

Third, the battle will be life-and-death. Fail and we perish.

Fourth, our sternest adversary will be ourselves. Our own fears and self-limiting beliefs. We must overcome our own faltering hearts before we achieve the redemption and fulfillment we seek.

All four of these factors were true of the Israelis in ’67.

All four have certainly been true of the struggles in my own life and I would wager they’re true universally.

Okay, back to you and me as writers …

We’ve identified our theme.

Now: how does this help us? Is it just an academic exercise or does it pay off in the real world? Will it help us write our book and, if so, how?

First, knowing the theme gives us our climax.

The emotional climax of The Lion’s Gate, we now know, must take place at the Western Wall, when the Israeli paratroopers take control of the Old City of Jerusalem. Somehow we have to structure the book to make the narrative end here.

Second, theme gives us our villains.

There are two. The Arab armies fighting against the Israelis. And the fears and self-doubts of the Israelis themselves.

Third, theme gives us our point of view. (Remember Paddy Chayefsky: “Once I know my theme, I cut everything that is not on-theme.”) Thus every scene in the book must be slanted around the idea of exile, of the “missing piece” of our soul, and of the hopes, fears, and hesitancies around reclaiming it.

Fourth, theme gives us our hero.

Our protagonist will be the Israeli people themselves, specifically the individual warriors, male and female, who fought the war and whom I will find and interview.

You may ask, “Steve, how did you keep these individuals ‘on-theme’ if you were interviewing people you had never met before and you had no idea what stories they would tell you or from what point of view they would tell those stories?”

The answer is I framed my questions around this theme. And, oddly enough, most of the time I didn’t have to do even that. The answers came out spontaneously on-theme.

Specifically:

One helicopter pilot told me of a visit with his younger brother (who happened to be the most decorated officer in the Israeli army) outside the walls of the Old City a few days before the war, in which both brothers expressed their pain at being debarred for so long from access to the Western Wall and from the Old City (both brothers had been born in Jerusalem and grown up there) and their hope that, if war came, they might get the chance to reach this ultimate goal.

Another paratroop captain told me of treks he took throughout his youth to Jerusalem, just to stand at a vantage point outside the city, straining on tiptoe to gain a glimpse not of the Western Wall itself, which could not be seen, but only of a poplar grove that stood above it.

This captain, it turned out, would be the first officer to reach the wall on June 7.

As I was recording these interviews and hearing these stories, I was thinking, “Ah, this is Chapter One!” Or, “This can go right before the climax!”

Fifth, theme gives us our title. (It was Shawn who actually came up with it.)

The Lion’s Gate is a gate in the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. It’s the gate by which the Israeli paratroopers entered on the seventh of June when they reached the Western Wall. A perfect title for a book on this theme.

I hope these personal specifics are not too excessive. My aim is to share my process, for one nonfiction book, and to demonstrate how Theme was absolutely primal and essential to the whole adventure.

To be totally candid it’s possible that I (or another writer) might have structured, researched, and written this book (or any other book) without knowing the theme. I confess I’ve done it before.

But when you do that, you’re operating 100% on instinct. That can work, true. It can work brilliantly.

But then what happens (and I’m speaking from experience) is you write 1500 pages to get 800, because you have to cut so much to reconfigure the book until it’s on-theme. And then you have to whack another 400 pages to make it focused and sharp and lean.

In other words, on a three-year project you can waste an entire year. Worse, such hardship can break your spirit (or your bankroll) and cause you to give up the project entirely.

Start with theme. For fiction or nonfiction. Ask yourself, “Why am I so drawn to this material? What, at its very core, draws me to it?”

That’s your theme.

Take it and run with it.