The Sudan Military Railway: A Most Effective Weapon

Few people interested in the wars and campaigns of the late-Victorian period will have failed to come across Kitchener’s re-conquest of Sudan between 1896 and 1898. Indeed, the Battle of Omdurman remains one of the most well-known actions fought during the Queen’s reign, and it made the reputation of one of Britain’s best remembered generals. However, few are aware of the Sudan Military Railway, which was so vital to the winning of the campaign, and even fewer truly understand its significance as being the most effective weapon employed against the Mahdists.

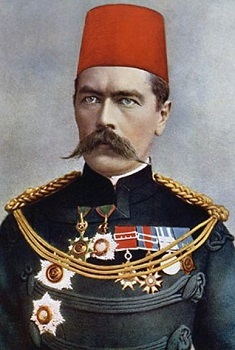

Major-General Kitchener, Sirdar of the Egyptian Army

Following the death of Charles ‘Chinese’ Gordon and the loss of Khartoum, Britain attempted to largely stay out of Sudanese affairs, showing a reluctance to confront the Khalifa and avenge the killing of their beloved general. After all, Sudan was an Egyptian problem and not one worth spilling the blood of British troops, who, inevitably, would be required in large numbers to wrestle control of the country from the fanatical Mahdists in order to restore it to Egyptian control.

A detailed account of how the British finally came to take the decision to re-conquer Sudan over a decade after its loss is beyond the scope of this short article, but needless to say the time eventually arrived when the Egyptian Government in Cairo, with the blessing and backing of the British Government in London, embarked on what would be a gradual and drawn-out operation to destroy the Mahdists and recover the lost territory. The campaign, which involved a number of actions and several major battles, effectively ended in success on 2 September 1898 at the Battle of Omdurman, although the Khalifa would not be killed until the following year. How, however, did the humble railway become key to this success?

As any student of military history will know, the issue of logistics is of paramount importance to winning any war or campaign. It is true that most are predominately drawn to the actual fighting aspect of military history, but there is usually a whole host of support mechanisms in place to supply and service the fighting troops, without which the latter could not realistically hope to operate successfully. The railway, built across Sudan, helped not only move the fighting men to and from the front, but it also kept them supplied with just about everything they needed. Traditionally in this theatre of war, supplies were transported on boats along the Nile or via camels across the desert, but the former was restricted by the numerous – and often impassable – cataracts, while the latter required an incredible number of animals to carry enough supplies to supply the 25,000 men who would eventually make up the Anglo-Egyptian army in Sudan.

The answer to Kitchener’s supply problems was, of course, to build a railway, but that in itself presented a number of huge problems that had to – one way or another – first be overcome. Firstly, many professional railroad builders in Britain believed that constructing a line across the Sudanese desert – terrain which was thought to be mostly sandy or rocky – would be totally unsuitable for the laying of track. Secondly, it was also thought that no sources of water would be found in adequate quantities in order to supply the thousands of workers required for such an ambitious project. Thirdly, no reliable maps were known to exist and so the intended route was an almost unknown. Fourthly, the territory through which the line would run was infested with hostile Mahdists, who were highly unlikely to stand and watch the invader get on with the construction unobstructed. Kitchener, however, had no intentions of letting such minor details stop him from building the line.

Kitchener turned to Édouard Percy Cranwill Girouard, a Canadian officer in the Royal Engineers who had a background as a railway builder with the Canadian Pacific Railways prior to his joining the army, after which he took charge of the Woolwich Arsenal Railway in Britain. Joining Kitchener’s expedition to Dongola in 1896, the engineer immediately set to work extending the existing line to Dongola, following the advancing troops as closely as possible. In this task he encountered a number of obstacles, chief amongst which was the poor quality of the workers at his disposal, most being unenthusiastic criminals. However, he managed to overcome his problems and greatly contributed to the success of the 1896 campaign.

Édouard Percy Cranwill Girouard, Royal Engineers

Perhaps the real triumph of the railway, however, came in 1897 and 1898, following Kitchener’s extension of the campaign from merely occupying Dongola to the retaking of Khartoum itself, which lay much further south along the Nile. The plan was to build a new line from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamed, which would greatly reduce the line of advance by about 330 miles, since the route would be direct and not follow the winds and bends of the Nile. Girouard even travelled back to Britain in order to find suitable locomotives, carriages and other equipment to build his railway, during which he met with Cecil Rhodes who agreed to loan him several engines for no fee.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Edward Cator of the Royal Engineers had conducted a survey along the intended route, and, to Kitchener’s delight, the terrain was found to be more suitable for the laying of track than had been previously believed. The lieutenant even identified several locations where water could be found in large enough quantities to sustain the workers as they built the line.

Work on the new line commenced on 1 January 1897, the surveyors marking out the route, after which the bankmakers followed, building embankments or otherwise cutting their way along the route. Next came the platelayers, who installed the wooden sleepers upon which the tracks were laid, followed by the spiking gangs, who would spike the tracks into place to ensure they did not move. Finally, the locomotives and the wagons could move along the line carrying their precious cargoes of men, supplies and equipment. The railway even carried a number of gunboats, which were broken down into sections then reassembled further up the Nile. Due to the cataracts and other obstacles, these vessels may not have been able to play the part they did in the campaign, but the railway allowed them to bypass the blockages.

Without the railway, Kitchener would had to have relied solely on the Nile and animal transport in order to move men and supplies from Egypt to the front. Such a reliance, even if realistically possible, would have resulted in a longer campaign and possibly a greater loss of life. It is, however, thanks to Kitchener’s forceful personality and the engineering talents of Girouard that such a seemingly impossible task was completed nonetheless. It truly was the most effective weapon employed against the Mahdists during Kitchener’s re-conquest of Sudan.

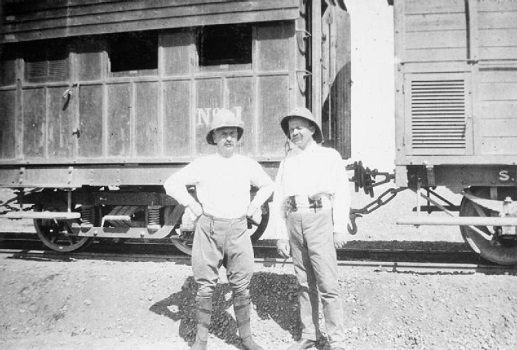

Kitchener’s intelligence officer, Colonel Sir Francis Wingate (left), in front of several trucks of the Sudan Military Railway

It is perhaps fitting to end this article with the words of Winston Spencer Churchill, who was present during the campaign in 1898:

‘In a tale of war the reader’s mind is filled with the fighting. The battle—with its vivid scenes, its moving incidents, its plain and tremendous results—excites imagination and commands attention. The eye is fixed on the fighting brigades as they move amid the smoke ; on the swarming figures of the enemy ; on the General, serene and determined, mounted in the middle of his Staff. The long trailing line of communications is unnoticed. The fierce glory that plays on red, triumphant bayonets dazzles the observer; nor does he care to look behind to where, along a thousand miles of rail, road, and river, the convoys are crawling to the front in uninterrupted succession. “Victory is the beautiful, bright-coloured flower. Transport is the stem without which it could never have blossomed. Yet even the military student, in his zeal to master the fascinating combinations of the actual conflict, often forgets the far more intricate complications of supply.’