Picture a yellow square rotating towards you... picturing things, aphantasia and reading and writing picture books by Juliet Clare Bell

When I was a child, we used to play this game: my dad would tell us all to shut our eyes in the car when we weren’t too far from home and then he’d drive and –still with our eyes shut- we’d have to tell him when we were home. To me, it was a bit like magic. The car would eventually stop and I’d assume we were home –because we’d stopped. But my sister would confidently say, eyes still shut: “You’ve cheated! You’ve taken us down Monks Hill instead! We’re by the field!” And she’d be right. How on earth did she know?

(This is where we should have ended up, outside our house -pictured here with some siblings and neighbours...)

(This is where we should have ended up, outside our house -pictured here with some siblings and neighbours...)

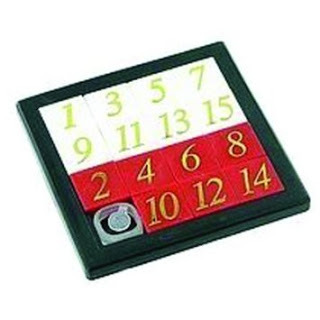

I was always getting lost, and had to accept that although I could do really well on certain things and tests, there were some things that other people found easy that for me were impossible, like those puzzles where you had to move the squares around to un-jumble a picture,

(I actually had this one as a child. What cruel trick to be given something like this...)

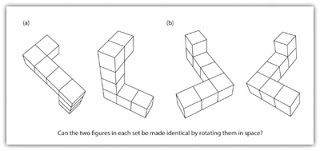

(I actually had this one as a child. What cruel trick to be given something like this...)or work out which of a group of drawn objects were actually the same but rotated (?!)

(I was one of those children who actually loved IQ tests and maths tests, but these questions were impossible.)

(I was one of those children who actually loved IQ tests and maths tests, but these questions were impossible.)and worst of all, and obviously designed to make me feel way more stressed than I ever was about anything else, those 3D wooden puzzles that you took apart and were then meant to reassemble. As someone who found lots of things easy as a child, these things could turn me into a jibbering wreck...

(Even looking at that middle one now -we had one the same at home- is making my heart race.)

(Even looking at that middle one now -we had one the same at home- is making my heart race.)It wasn’t until I was seventeen and travelling home from college on the train with a friend that I made a crazy discovery…

We were just chatting and my friend said: “Close your eyes and picture a yellow square rotating towards you…” I didn’t know what she meant, so she repeated it. What on earth did ‘picturing’ mean? I’d always assumed that it was a metaphor. Turns out…

…other people could picture things when they closed their eyes! How totally, utterly, bafflingly weird was that? Except that other people seemed to find it as bafflingly weird that I didn’t...

So it turned out that other people could picture their mum if they closed their eyes and she wasn’t actually there.

(My mum. Who knew you could close your eyes and see the kinds of things you could see when you looked at photos, or the world around you?)

(My mum. Who knew you could close your eyes and see the kinds of things you could see when you looked at photos, or the world around you?)And, as my sister who used to know where we were going in the car even with her eyes shut, told me, when she's working out where she's going, she pictures a map from above, like an aerial view of streets (excuse me?) when she’s walking around.

I’d never read anything about this until a couple of months ago when a fellow writer, Addy Farmer, wrote about it. She mentioned the famous 19th century psychologist, Galton, who’d done some research into this and found that people who pictured things just assumed other people pictured things, and people who didn’t, didn’t (well –it would never even cross their minds that something that bizarre was going on in other people’s heads).

Not picturing things is called aphantasia (which sounds a little too close to an 80s pop group for my liking), and you can do a quiz here (run by researchers at Exeter University, who are doing research into it). For me, most of the questions didn’t even make sense.

I’ve had very visual people feel sorry for me –but I’ve never known any different, and I don't feel like it's been difficult without. When I went to university and for a long time after, I used to have a wall plastered with photos of people that I was no longer living with/seeing all the time, which gave me enormous pleasure and I’d really look at them every day so I was still seeing them even if I was doing it in a different way from other people (not that it ever crossed my mind back then why I did this). I love chatting with other people so asking for directions is hardly a chore. My auditory memory was great –it was easy to learn lines, remember all the lyrics to songs, recount the whole of the previous night’s Neighbours(bad accents ’n all) to people in school who’d not seen it…

(My auditory memory was great, and it was useful when someone else had missed the previous night's episode of Neighbours...)

(My auditory memory was great, and it was useful when someone else had missed the previous night's episode of Neighbours...)And a recent long discussion with a friend about it has made me realise that it’s probably informed how I view my life. My friend relives arguments and difficult moments –and nice moments- over and over again, vividly, with visual detail –and it’s not always in her control to stop seeing things that she doesn’t want to see…

And so aphantasia probably helps me live more in the present and let go of the past: although it was extremely sad when my husband and I were going to split up (and the run up to it, when I was living it every day was extremely painful), I’m never haunted by closing my eyes and seeing pictures of us being happy together. If I don’t look at pictures of him, I don’t see him. And I still don’t know what colour his eyes are, even though I’ve looked into them thousands of times. I still remember the happy emotions associated with lots of the relationship, so I can talk genuinely happily with the children about some of the great times we had together –but I don’t visualise them. And I’d never be haunted by imagined images of him with someone new, which apparently other people are, which must be grim. Similarly, I don’t visualise being attacked by someone in my mid-twenties and I can't remember what he looked like at all. And it probably partly accounts for my being less bothered by my appearance than some people (unless I’m in front of a mirror, it wouldn’t cross my mind how someone else might be viewing me –unless I actively tried to think about it). And I don't crave expensive exotic holidays. They’d be lovely whilst I was there, I suspect –and I'd love hanging out with the people I was with, but I wouldn't be reliving any beautiful sights again. For me, grass just isn’t greener on the other side. You make the most of exactly where you’re at because the other stuff is kind of not even there… it seems that for some other people, the If onlys… and what ifs… are far more present. And I probably have my lack of visual imagination to thank for a large part of that.

But there is a point to this in relation to reading and writing and picture books.I love books and reading. At the end of reading a book I have no more idea what a character looks like than at the beginning. I skip descriptive passages because they mean nothing. Although I love her poetry (which for me is about the words and the sounds and the emotion), I could never read Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights as it’s so full of description I just can’t follow it.

Does this matter? Not to me –I love books which resonate with me emotionally; physical description is irrelevant for that. And there are so many different kinds of book that there are always going to be loads that I’d love. And whether or not it’s coincidental (I suspect not), it turns out that the author of one of my favourite books (Tall Story), Candy Gourlay, doesn’t picture things either…

(Candy doesn't visualise things, either. And her books are fab.)

(Candy doesn't visualise things, either. And her books are fab.)So how does this tie in with writing picture books? I love picture books, especially where a lot of the story is told through the pictures, like:

Not Now, Bernard, by David McKee

and The Baby That Roared by Simon Puttock and Nadia Shireen

and Oh No, George! by Chris Haughton

And that’s great –and easy, as I can just look at the pictures and they’re there.But for picture book writers who don’t visualise things but still love to write books where as yet un-drawn images are a really important part of the story, how does that work? I’d love to hear from other picture book writers as to how they do it and whether most of them visualise the image. I don’t know how it works with me but I do know that I can easily leave space for the pictures when I'm writing, and that I love doing it. Do I imagine what that picture would look like? Well I guess I do in a way –I think that it would need to contain certain things. Do I visualise it? No. But I would know that it needed to reveal a specific thing that’s not yet been mentioned in the text, or show an emotional reunion –just without knowing what that scene would look like. And that’s the illustrator’s job anyway…

Maybe I love picture books so much because I’m not visual. Picture books are a visual experience for me whereas reading a novel certainly isn’t a vaguely visual experience… I’d love to hear from other writers and illustrators about how important picturing things is for them –is it real or just a metaphor? And for readers, what’s your experience of reading books? I’d love to know the kinds of books that other non-visual people like to read –and what they like to write. Please share your visual or non-visual experiences below.

Let's finish by celebrating our differences. Loads of things go into what we choose to write and how we write it. Picturing things may be part of how some people write, but so might not picturing things. I certainly wouldn't consider it a disadvantage...

Hooray for the different way different writers think... (with thanks to my jumping children)

Thank you.

Juliet Clare Bell’s first true story picture book, Two Brothers and a Chocolate Factory: The Remarkable Story of Richard and George Cadbury, illustrated by Jess Mikhail, is out on March 19th. Her last book, The Unstoppable Maggie McGee (illustrated by Dave Gray) has raised over £40,000 in sales so far for Birmingham Children’s Hospital’s Magnolia House Appeal. www.julietclarebell.com

Published on March 14, 2016 04:37

No comments have been added yet.