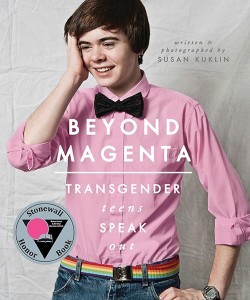

Book Review: Beyond Magenta

A 2015 Stonewall Honor Book, Beyond Magenta looks at six young people and their gender identity, encompassing individuals who identify as trans, intersex and non-binary. Author Susan Kuklin keeps her own comments to a minimum as she transcribes interviews with these people, interspersing the text with images; the afterword reveals that the interviewee had the chance to read through the material before publication to ensure it was an accurate depiction of their take on things.

I wanted to love this book, to connect with it, to be able to point to it when I’m teaching or working with young trans or genderfluid humans and say, hey, yeah, that book really got it. But I don’t think it does. In so many ways it feels dated already – it uses the term ‘transsexual’ much more than ‘transgender’, for example, and the idea of ‘cisgender’ never once makes an appearance. And as hypercritical as Goodreads reviews can be, I have to agree with those who’ve noted that the range covered here is very small – we’re looking at individuals within a big city (New York), mostly attending the one clinic. There is racial diversity even within this, but it doesn’t seem representative of trans teens overall – what about those, for example, who don’t have access to therapeutic and hormonal treatments?

And the book does itself no favours by having, in its first two sections, two people whose trans identity seems entirely predicated on outdated stereotypes. Jessy reports that, “Everything I’ve learned as a man comes from my father. Be strong. Don’t cry. Don’t whine.” Maleness is linked with doing sports and not being girly. It gets even worse with Christina, who talks about how she loves shopping and not sports, and recounts this conversation with her therapist:

“I don’t know. I just want to finish college and get a job and have a husband. I just want to be a housewife. I want to cook and I want to clean. I want to take care of the kids. I want to do all that.”

“You know what you sound like? You sound like a traditional woman.”

“What do you mean?”

“Everything that you’re saying is from a woman’s perspective. Staying home, cooking, taking care of kids. That’s what women do, traditionally. That’s what they were known to do.”

“Okay, then, I guess I’m a traditional woman.”

There are certainly points to be made about the extent to which trans individuals can feel under pressure to perform their gender roles in a very extreme, idealised way – to prove their femaleness with heightened femininity and to feel that wearing more gender-neutral attire might cause others to question their status as women. Or to prove their maleness with aggressiveness, although this seems to be less of an issue. But reducing gender identity to 1950s ideas of the perfect housewife is depressing.

Other accounts are more nuanced, explaining, “It was like I’m not born who I am, I have to transition to be who I am.” Cameron, preferring they/their pronouns, addresses the hormone question by saying, “I tried to help my parents understand how much more comfortable hormones will make me… I emphasized that hormones will help with all the awkward moments in public when people misgender me.” They also offer up astute comments on the way in which the gender binary doesn’t work for so many people, and how despite being read as masculine, they are not interested in adopting stereotypical behaviour. I also adored the final section, focusing on Luke’s experience with slam poetry – “There’s a lot you can say in poetry that you can’t say in conversation” – and theatre as means of self-discovery and self-expression. An entire book along these lines would have been welcome.

So, no, it’s not a book I’ll be recommending in its entirety to young people, or indeed to anyone. I wanted it to be. But even the resources feel out of date – the two (two!) fiction suggestions are Jeffrey Eugenides’s Middlesex and Julie Anne Peters’s Luna – and while we certainly need more books about the trans experience, particularly for young people, we also need better books than this.