Writing While Black/Writing While Indigenous: Two voices speak on excellence

Ambelin: How to begin to speak about excellence? I’m worried that in speaking I’ll contribute to the phenomenon whereby Indigenous writers and writers of colour are held to impossibly high standards, while white writers are often held to no standard at all when it comes to the representation of others. I’m aware that I have no right to tell other Indigenous writers or writers of colour what should constitute excellence for them; we are diverse peoples with diverse cultures, experiences and histories, and all these things influence our individual views on excellence. But I still think there is a place for all diverse writers to personally reflect on what excellence means to each of us, and I believe it’s an important conversation to have. Zetta, you wrote in your first post that you were “tired because the fight seems never-ending, and progress minimal.” I feel the same. On the worst of days, I do what the generations who came before me did – I take the long view, gazing beyond the span of my existence into the undetermined future. And I think about how powerfully it matters to have the voices of so many diverse peoples speaking to these issues in cyberspace. We are creating a record, and if we don’t succeed in changing anything for ourselves, we will at least place our knowledge and insights into the hands of the writers who come after us.

Ambelin: How to begin to speak about excellence? I’m worried that in speaking I’ll contribute to the phenomenon whereby Indigenous writers and writers of colour are held to impossibly high standards, while white writers are often held to no standard at all when it comes to the representation of others. I’m aware that I have no right to tell other Indigenous writers or writers of colour what should constitute excellence for them; we are diverse peoples with diverse cultures, experiences and histories, and all these things influence our individual views on excellence. But I still think there is a place for all diverse writers to personally reflect on what excellence means to each of us, and I believe it’s an important conversation to have. Zetta, you wrote in your first post that you were “tired because the fight seems never-ending, and progress minimal.” I feel the same. On the worst of days, I do what the generations who came before me did – I take the long view, gazing beyond the span of my existence into the undetermined future. And I think about how powerfully it matters to have the voices of so many diverse peoples speaking to these issues in cyberspace. We are creating a record, and if we don’t succeed in changing anything for ourselves, we will at least place our knowledge and insights into the hands of the writers who come after us.

Zetta: Agreed! And I feel the same way about my books. A white woman once remarked that self-published books rarely sell over 100 copies and I thought to myself, “So?” In her mind, that makes the act of self-publishing futile but to me, reaching 100 kids and potentially transforming their lives is not a waste of time. I really want to explore the connection between quantity and quality in the kid lit community. No doubt most writers aspire to see their book on the New York Times Bestseller list, but does that in any way indicate excellence? If 3000 novels for young readers are published annually in the US and only 30 are by Black authors, what does that do to the potential for excellence? Black-authored books in the US are eligible for the Coretta Scott King Award, a prize reserved for African Americans authors and illustrators. But the same people win the award over and over again. Kyra Hicks finds that from 1970-2012,

…authors or illustrators who have received two or more CSK awards or honors account for the majority of all award recipients. For example, 26 African-American authors (33 percent) have been honored with 67 percent of all the author awards given since 1970. And, 17 Black illustrators (40 percent) have 75 percent of all the illustrator awards given.

In 2015 there were only 2 debut Black authors with middle grade or young adult novels. Can we achieve excellence without competition? Are award committees really rewarding excellence when the majority of Black writers can’t even get a foot in the door? In the 19th century, slave narratives had to be authenticated by Whites in order to be deemed legitimate, and formerly enslaved women and men had to self-censor at times in order to avoid offending the “delicate sensibilities” of their genteel White audience. One could argue that this authentication process continues to this day since the publishing industry is dominated by White women.

Perhaps our academic background makes us accustomed and/or indifferent to the limited circulation of significant texts. Perhaps our cultures have taught us that writing is not just for the self but for the community—and every member of the community counts. With this important dialogue we are creating an archive, inserting ourselves into history because these conversations do leave a digital footprint that may guide someone somewhere who feels lost and alone.

Ambelin: And that footprint is so necessary – because diverse writers cannot rely on the people whom writers are supposed to be able to rely upon. Most agents, editors, and reviewers don’t know enough about us to be able to give us meaningful feedback on the ways in which we are representing our worlds – in fact, their advice may well be wrong. I know that I am far from the only Indigenous author to have been told that I am not writing to the ‘Indigenous experience’ (as if there is only one experience shared amongst the vast diversity of the Indigenous peoples of the earth, and as if that experience has been accurately captured by the works produced about us by white people, which is generally the frame of reference against which my writing is being judged). So I must seek other processes to help me achieve excellence. As part of this, I read all I can find written by Indigenous and other diverse peoples on writing and representation. Everything I write is reviewed by other Indigenous people before it is published. If I am in doubt as to whether something should be said, I do not speak. And I am as sensitive as I can be to the contexts in which things will be read, to the many ways in which my words can misread and misinterpreted.

Ambelin: And that footprint is so necessary – because diverse writers cannot rely on the people whom writers are supposed to be able to rely upon. Most agents, editors, and reviewers don’t know enough about us to be able to give us meaningful feedback on the ways in which we are representing our worlds – in fact, their advice may well be wrong. I know that I am far from the only Indigenous author to have been told that I am not writing to the ‘Indigenous experience’ (as if there is only one experience shared amongst the vast diversity of the Indigenous peoples of the earth, and as if that experience has been accurately captured by the works produced about us by white people, which is generally the frame of reference against which my writing is being judged). So I must seek other processes to help me achieve excellence. As part of this, I read all I can find written by Indigenous and other diverse peoples on writing and representation. Everything I write is reviewed by other Indigenous people before it is published. If I am in doubt as to whether something should be said, I do not speak. And I am as sensitive as I can be to the contexts in which things will be read, to the many ways in which my words can misread and misinterpreted.

Zetta: I just wrote about this last month when I took issue with a Black-authored book that completely erased young Black women from the Black Lives Matter movement—even though it was founded by young queer Black women. That YA novel went on to win numerous awards and the Black male author ultimately took responsibility for “missing the mark,” which only further impressed his many (white female) fans. People on social media remarked about our exemplary exchange—“so civil!”—but said very little about what it means that this book got published to great acclaim without anyone else noticing (or caring) that it potentially harms young Black women. In a follow-up post I wrote,

Zetta: I just wrote about this last month when I took issue with a Black-authored book that completely erased young Black women from the Black Lives Matter movement—even though it was founded by young queer Black women. That YA novel went on to win numerous awards and the Black male author ultimately took responsibility for “missing the mark,” which only further impressed his many (white female) fans. People on social media remarked about our exemplary exchange—“so civil!”—but said very little about what it means that this book got published to great acclaim without anyone else noticing (or caring) that it potentially harms young Black women. In a follow-up post I wrote,

…whenever a problematic book comes out, it points to a failure of process. Writing is a solitary activity, but publishing a book is not. It would have been great if the editor of this novel thought about the exclusion of Black girls. It would have meant a lot to me if some reviewers gave the book the praise it deserves but also pointed out this particular limitation. The fact that neither of those things happened confirms for me that a lot of people in the kid lit community aren’t really thinking about Black girls. I don’t generally review books but I published my critique on my blog because I was trying to be strategic. I’ve only met Jason once, but he seemed like an open-minded person and the comment he left on my blog proves that to be true. I also heard he has a ten-book deal, which means he’ll have plenty of opportunities to write (better) Black female characters in the future. Will reviewers and librarians and editors educate themselves about intersectionality and misogynoir? I doubt it. And that puts the onus on the writer—WE have to work harder because we can’t rely on others in the publishing process to get it right. No writer is perfect—I make mistakes all the time. But I care about Black youth and I know Jason does, too. And that’s why we have to help and look out for one another.

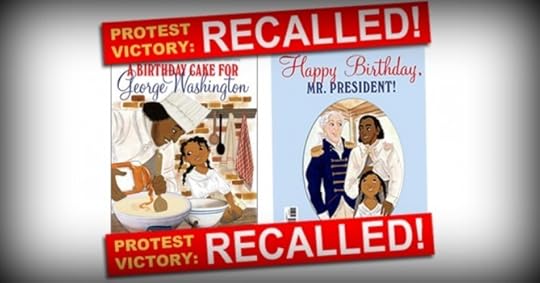

Yet as Scholastic’s controversial publication and recall of A Birthday Cake for George Washington makes clear, having a Black editor doesn’t guarantee that a book about an aspect of the Black experience will be properly vetted. Editors don’t always recognize that different cultural groups have particular storytelling conventions, but cultural competence isn’t the only issue. As you pointed out in your first post, storytelling plays a crucial role in the ongoing struggle for liberation but I suspect most people involved in the kid lit community don’t see the publication and promotion of children’s literature as a political act. Many would agree that books can empower young readers, but few seem to recognize that inaccurate and/or insensitive books can be toxic.

Ambelin: I think, too, that its important to many of us to honour the lives (and the struggles) of all marginalised peoples, not only the groups we belong to. But intersectionality is not an easy thing to address within the limits of a narrative – so do we find ways to convey where different experiences connect and diverge? Where are the spaces for diverse writers to have these conversations amongst ourselves in the first place? And how do we remain true to who we are whilst continually negotiating literary spaces that are not our own and reflect nothing of our identities? I don’t think any of these questions have easy answers. One of my picture books has been criticised as being didactic. The criticism is correct in that it is didactic. But in non-Western cultures, including Indigenous cultures, didacticism is not necessarily a negative; and amongst the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, stories often ‘circle back’ to the message of the tale. I am not suggesting that Indigenous cultures are incapable of change such that we must always tell stories within specific fixed and unvarying forms; a view of Indigenous cultures as frozen relics is a myth generated by anthropological texts and other colonial works of epic fantasy. Nor am I suggesting that I, or any Indigenous writer, is a passive victim of Western literary forms; I am as capable of resistance and subversion as my ancestors were in their long battle against colonialism. But for this particular story, I concluded that it needed to be told in this particular way. It drew adverse comment for didacticism from white reviewers. It is also the book which Indigenous people – and other peoples from non-Western backgrounds – regularly tell me is their favourite of my works. My conclusion is this: in order to be true to myself as an Indigenous writer, there will be times when I must contravene Western literary ideals of what it means to be excellent.

Ambelin: I think, too, that its important to many of us to honour the lives (and the struggles) of all marginalised peoples, not only the groups we belong to. But intersectionality is not an easy thing to address within the limits of a narrative – so do we find ways to convey where different experiences connect and diverge? Where are the spaces for diverse writers to have these conversations amongst ourselves in the first place? And how do we remain true to who we are whilst continually negotiating literary spaces that are not our own and reflect nothing of our identities? I don’t think any of these questions have easy answers. One of my picture books has been criticised as being didactic. The criticism is correct in that it is didactic. But in non-Western cultures, including Indigenous cultures, didacticism is not necessarily a negative; and amongst the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, stories often ‘circle back’ to the message of the tale. I am not suggesting that Indigenous cultures are incapable of change such that we must always tell stories within specific fixed and unvarying forms; a view of Indigenous cultures as frozen relics is a myth generated by anthropological texts and other colonial works of epic fantasy. Nor am I suggesting that I, or any Indigenous writer, is a passive victim of Western literary forms; I am as capable of resistance and subversion as my ancestors were in their long battle against colonialism. But for this particular story, I concluded that it needed to be told in this particular way. It drew adverse comment for didacticism from white reviewers. It is also the book which Indigenous people – and other peoples from non-Western backgrounds – regularly tell me is their favourite of my works. My conclusion is this: in order to be true to myself as an Indigenous writer, there will be times when I must contravene Western literary ideals of what it means to be excellent.

Zetta: The novel I’m about to publish (The Door at the Crossroads, sequel to A Wish After Midnight) was also called “didactic” years ago by one of the very few woman of color editors in Canadian children’s publishing. In this case, I think she was reacting to the explicit political content of the book, which I was unwilling to remove or water down. I think most editors—regardless of race—envision the audience for kid lit to be White middle-class kids and teens. And they no doubt realize that the overwhelming majority of educators and librarians purchasing books for schools are also White and middle-class. But since White middle-class readers are definitely NOT my target audience, I resent being asked to alter my story to keep them comfortable. Right now I have a few beta readers looking at Crossroads; one White woman reader said she found the novel hard to read and yet couldn’t put it down, and a Black woman reader said the characters’ harrowing escape from slavery in the book was making it hard for her to be around Whites in real life. That tells me my book is doing exactly what I want it to do. Literature that appeases its readers just upholds the status quo and I want my books to disrupt, disrupt, disrupt! I think Black excellence has a lot to do with risk, and the publishing industry is notoriously risk-averse even as it is also self-congratulatory (same with Hollywood, and the lily-white Oscars are on as I write this). A young Black woman author just got a six-figure advance for a YA novel about the Black Lives Matter movement. Will there be queer Black women in this book? I hope so, but I’m not holding my breath. And even if it does have radical content, one book—and one book deal that enriches one author—is NOT a sign of progress. It costs the industry nothing to make a gesture like that because nothing about the structure of the industry—and the balance of power—has to change.

Zetta: The novel I’m about to publish (The Door at the Crossroads, sequel to A Wish After Midnight) was also called “didactic” years ago by one of the very few woman of color editors in Canadian children’s publishing. In this case, I think she was reacting to the explicit political content of the book, which I was unwilling to remove or water down. I think most editors—regardless of race—envision the audience for kid lit to be White middle-class kids and teens. And they no doubt realize that the overwhelming majority of educators and librarians purchasing books for schools are also White and middle-class. But since White middle-class readers are definitely NOT my target audience, I resent being asked to alter my story to keep them comfortable. Right now I have a few beta readers looking at Crossroads; one White woman reader said she found the novel hard to read and yet couldn’t put it down, and a Black woman reader said the characters’ harrowing escape from slavery in the book was making it hard for her to be around Whites in real life. That tells me my book is doing exactly what I want it to do. Literature that appeases its readers just upholds the status quo and I want my books to disrupt, disrupt, disrupt! I think Black excellence has a lot to do with risk, and the publishing industry is notoriously risk-averse even as it is also self-congratulatory (same with Hollywood, and the lily-white Oscars are on as I write this). A young Black woman author just got a six-figure advance for a YA novel about the Black Lives Matter movement. Will there be queer Black women in this book? I hope so, but I’m not holding my breath. And even if it does have radical content, one book—and one book deal that enriches one author—is NOT a sign of progress. It costs the industry nothing to make a gesture like that because nothing about the structure of the industry—and the balance of power—has to change.

Ambelin: I am always so happy to hear of the successes of other diverse writers – I know how heavily the odds are stacked against all of us. But as you rightly point out, the success of some isn’t evidence of those odds changing. A world of literature that reflected the make up of the actual world (in regard to both who gets published, and who is working in the industry) would be evidence of change, and we’re a long way from that. The individual voices of the marginalised should be difficult for people to make out not because the structures of privilege prevent us from speaking, but because there are so many of us speaking that we overwhelm with our multitude, with our wealth of stories that shout out the many truths of our existence. Instead, there are so few of our voices to speak to the struggles and triumphs of so many. I feel the weight of that, heavy upon my shoulders. In a YA context I write Indigenous futurisms, a form of storytelling whereby Indigenous peoples use the speculative fiction genre to challenge colonialism and to envision Indigenous futures. In drawing on colonial history, I believe I have a dual responsibility. The first aspect of this responsibility is to speak to the truth of Indigenous resistance and agency, and in so doing, deny the lie that we were unresisting victims who faded away in the face of the so-called ‘superiority’ of Western cultures. The second aspect is to convey the way in which colonialism wounded – and ended – the lives of so many. The triumphs of oppressed peoples is a tribute to the spirit of the oppressed. It does not – ever – make the oppression any less evil that it was. And I think there is a danger that narratives which speak to our triumphs can be interpreted by those whose ancestors did not experience these histories (or the present-day disadvantage, discrimination and multigenerational trauma that resulted) as indicating that things were ‘not that bad’. So I believe excellence in this context means celebrating the incredible spirit of Indigenous peoples, but doing so in a way that always names colonialism and other forms of oppression for the evils that they were (and are).

Zetta: I couldn’t agree more. Speculative fiction operates differently without our cultures, and I worry that decades of Harry Potter mania will make is harder for kids of color to imagine themselves operating within magical worlds. In my 2014 essay “The Trouble With Magic,” I build upon Ramón Saldívar’s concept of “historical fantasy,”

…which “links desire and imagination, utopia and history, but with a more pronounced edge intended to redeem, or perhaps even create, a new moral and social order” (587). Saldívar contends that, “in the twenty-first century, the relationship between race and social justice, race and identity, and indeed, race and history requires [writers of colour] to invent a new ‘imaginary’ for thinking about the nature of a just society and the role of race in its construction. It also requires the invention of new forms to represent it” (574). Though Saldívar makes no mention of children’s literature in his discussion, I believe his assessment of contemporary American fiction should be extended to include the needs of young readers, who are more diverse than ever before yet rarely find books that confront the nation’s problematic, ongoing history of social injustice. By linking contemporary racial inequality to the history of enslavement and racial terror in New York City, my novels depart from the work of Ruth Chew by attempting to “reverse the usual course of fantasy, turning it away from latent forms of daydream, delusion, and denial, toward the manifold surface features of history” (Saldívar 595).

That essay can be found in any library database that includes Jeunesse: young people, texts, culture (you can also email me for a PDF). We can—and sometimes must—theorize about our work, but in the end I’m hoping our stories will help young people to theorize their own experience. Magical stories are always about power, and our youth need to know how to wield power and how power has been/is being used by others to oppress our communities.