Michael S. Heiser's Blog, page 78

March 16, 2012

Naked Bible News: Facebook, Twitter, and Podcasting

Hi everyone. Blogging has been a bit slow (on this blog anyway) for two reasons. First, there's the flurry of activity over this past week regarding the forgery trial in Israel concerning "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus" ossuary, as well as the new Talpiot B tomb (a tomb alleged to be related to the other Talpiot tomb, the so-called "Jesus Family Tomb"). The James ossuary is thought by promoters of that tomb to have originally been part of that tomb. I've been blogging on all that over at PaleoBabble if anyone is interested. Second, I've been tied up trying to be more deliberate about social media and podcasting. The latter prompts some news.

Twitter and (Not) Facebook

I've created a Twitter account so that when I post on any of my blogs, notification will appear there as well. I don't know much about Twitter. I think that if you click here you will go to my Twitter page and can decide to follow me or not. It might be a good way to be alerted right away when I post something (at least that's what I'm thinking — don't worry, I won't be alerting you to what I had for breakfast or whether my dog just did #1 or #2). As noted above, we'll see if it's working.

In case you're wondering why I don't send posts to Facebook, I tried setting up the Plugin and creating the necessary Facebook App for automatically posting notifications, but killed the idea as soon as Facebook wanted my credit card number for account "verification" (hey, how about the fact that I'm in your website, which required a password get there?). It will be a cold day in Sheol before I give the Facebook troll my credit card information. The site would also accept a mobile device but I don't have one. So that died a quick death.

Podcasting

Lastly, there is the podcast. That *might* begin this weekend. It has an "almost there" feel to it, but whenever I get that tingle I usually discover four or five things I haven't done correctly or have overlooked. But keep your eyes peeled. I will post episode alerts here that will have the actual podcast site link. If you follow that link you will be able to subscribe on iTunes at the actual podcast site. I'll also be archiving episode links on a podcast "page" here at the blog. The whole process has been more involved than I anticipated.

Stay tuned!

March 8, 2012

Logos Makes Puget Sound Business Hall of Fame

I don't often post about my employer, Logos Bible Software, but this one deserves mention: "Logos in Hall of Fame: Makes 100 Fastest-Growing Companies list fifth time." I post it since I know how much work has gone into the growth (and is still going into it). We are blessed with very competent executive leadership and talented people at all levels. The company has literally tripled in size since my first day back in 2004 (from 85 to now over 250 employees). And Logos is still looking for people.

March 6, 2012

Mosaic Authorship of the Pentateuch: Changes in Law in Deuteronomy

In my previous post on JEDP I said this post would be my last on that topic. In the intervening days I told someone in the comments page that I would add a post to the topic – the best example I can think of for changes made in OT law between Exodus and Deuteronomy. This post covers that example, and so the next post will be my last.

The commenter was curious about evidence for Deuteronomy re-purposing and adapting existing Torah laws for a later context. There are a number of examples of this, but in many cases someone could argue that Deuteronomy merely envisions being in the land and so the content of Deuteronomy at that point doesn't actually reflect a later period, but looks forward to the conditions of a later period. I like the example that follows because there is no way to coherently make that explanation in this instance. The only way to explain the difference between the law of Exodus and that of Deuteronomy is that the latter law changed the former in response to later historical circumstances – circumstances that post-dated the Mosaic period.

Exodus 21:1-6

Deuteronomy 15:12-18

1 "Now these are the rules that you shall set before them. 2 When you buy a Hebrew slave, he shall serve six years, and in the seventh he shall go out free, for nothing. 3 If he comes in single, he shall go out single; if he comes in married, then his wife shall go out with him. 4 If his master gives him a wife and she bears him sons or daughters, the wife and her children shall be her master's, and he shall go out alone.5 But if the slave plainly says, 'I love my master, my wife, and my children; I will not go out free,'6 then his master shall bring him to God (ha-elohim), and he shall bring him to the door or the doorpost. And his master shall bore his ear through with an awl, and he shall be his slave forever.

12 "If your brother, a Hebrew man or a Hebrew woman, is sold to you, he shall serve you six years, and in the seventh year you shall let him go free from you. 13 And when you let him go free from you, you shall not let him go empty-handed. 14 You shall furnish him liberally out of your flock, out of your threshing floor, and out of your winepress. As the Lord your God has blessed you, you shall give to him. 15 You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God redeemed you; therefore I command you this today.16 But if he says to you, 'I will not go out from you,' because he loves you and your household, since he is well-off with you,17 then you shall take an awl, and put it through his ear into the door, and he shall be your slave forever. And to your female slave you shall do the same. 18 It shall not seem hard to you when you let him go free from you, for at half the cost of a hired servant he has served you six years. So the Lord your God will bless you in all that you do.

In the left column we find the law concerning what needs to be done when a slave desires to stay in his master's household. It is a famous passage. Part of the procedure is that the master would impale the slave's ear with an awl (Hebrew: martsea') to the doorpost of his house, signifying his permanent membership. This Hebrew term is used only one other place in the OT, Deut 15:12-18, so there is no confusion that these two passages are certainly speaking of the same situation and law. There are some minor differences between the two passages, but one major one. In the Exodus passage, this symbolic act is to be done "before ha-elohim." The translation below translates ha-elohim as "God." As part of the rather poor argumentation against a divine council of divine elohim in Psa 82:1b, some apologists who want to argue that the elohim of Psa 82:1b are humans go to this Exodus passage. They argue that ha-elohim refers to Israelite judges or elders. This would mean that the master of the house pierces the slave's ear "before the human elders" (i.e., local authorities in Israel). So who is right? Is ha-elohim plural or singular, and does it refer to God or "gods" that are actually people?

Determining who is correct takes us into the parallel passage and its key change: there is no ha-elohim in the Deut 15 passage! It has been deleted. Why that change was made is directly tied to which view of ha-elohim is correct. Let's unpack things (what follows is taken from my ETS 2010 paper on Psalm 82, with minor editorial changes to make it readable).

First, ha-elohim could be semantically singular, referring to the God of Israel. The promise about the status of the slave is being made in truth before God. This is the simplest reading. However, there is evidence that the redactor-scribes responsible for the final form of the text did not interpret ha-elohim here as singular but plural—but ALSO did NOT interpret a plurality as referring to human beings! The key is the parallel passage in Deuteronomy 15. Later redactors apparently saw ha-elohim as semantically plural since the parallel to it found in Deut 15:17 removes the word ha-elohim from the instruction. This omission is inexplicable if the term was taken as singular, referring to YHWH for a simple reason: Why would the God of Israel need to be removed from this text? Moreover, if ha-elohim had been construed as plural humans, Israel's judges, the deletion is just as puzzling. What harm would there be if the point of the passage was that Israel's judges needed to approve the status of the slave?

The deletion on the part of the writer of Deuteronomy is quite understandable, though, if ha-elohim was intended as a semantically plural word that referred to gods, not people. Seventy years ago Cyrus Gordon pointed out that the omission in Deuteronomy appears to have been theologically motivated.1 Gordon argued that ha-elohim in Exod 21:6 referred to "household gods" like the teraphim of other passages, which represented one's deceased ancestors. Bringing a slave into one's home in patriarchal culture required the consent and approval of one's ancestors—departed human dead who were elohim (cp. 1 Sam 28:13, where the deceased Samuel is called elohim). Under a later redaction after the time of Moses this phrase was omitted from the Exodus law. The context would logically have been the time of some reformer like Josiah or Hezekiah, who did much to eliminate idolatry in the wake of Israel's struggle with idolatry during the Divided Monarchy under wicked kings. The fear prompting the editorial deletion was apparently that any reference to household elohim (teraphim figurines – sort of like our pictures of departed loved ones) might lead to a new spasm of idolatry.2 Only a plural referring to multiple divine beings can coherently explain the deletion. As a result, this passage is also no support for the plural human elohim view with respect to the argument over Psalm 82:1b. And it also shows a clear alteration of a law in Exodus at a later period in Deuteronomy, one that Moses could not have written. But, as I have noted in several posts in this series, calling the Torah "the law of Moses" is entirely appropriate and coherent in my view since its contents are overwhelmingly associated with the life and work of Moses irrespective of how much of its contents can be traced to his own hand.

Cyrus H. Gordon, "ELOHIM in Its Reputed Meaning of Rulers, Judges," Journal of Biblical Literature 54 (1935): 139-44. ↩

People did bring food offerings and libations to teraphim, but this should not be considered worship any more than our own practice of laying flowers, toys, photos, or other personal items at a gravesite. The purpose of such offerings was so that the deceased was not only honored, but also enabled to enjoy good things from the terrestrial world and to maintain a relational link to loved ones. We lay such items as a grave thinking it pleases our loved ones, or as a gesture of connection or remembrance. The same was true in ancient Israel. ↩

Technorati Tags: awl, Deuteronomic, Deuteronomist, editing, elohim, law, Moses, Pentateuch, slave, Torah

March 3, 2012

Mosaic Authorship of the Torah: Problems with the Documentary Hypothesis (JEDP), Part 3

I'm thinking this will be my next-to-last post on JEDP. The topic has not generated much discussion, so I'm going to move on. Can't say I'm surprised. I'm not all that interested in composition of the Pentateuch myself. Toward the end I'll sketch what I think. In this post I want to just give you a taste of what Friedman *doesn't* tell readers in his book: that several scholars in recent years (not Christian apologetics types) have expressed sincere doubt about JEDP, and have proposed other models. But all that would be the subject of a doctoral seminar, not a blog. So just a glimpse here.

In the last post, I noted that, while the idea that the Pentateuch has been edited and was not entirely composed by Moses is a coherent (and biblically driven) notion, the standard JEDP theory is dissatisfying. Here are the problems I've drawn attention to so far, with standard JEDP responses.

1. Nearly 100 instances where two Hebrew source texts disagree as to the name for God (Yahweh or Elohim). JEDP response: sloppy translator; the problem can't be the divine name criterion.

2. P vocabulary and concepts showing up in J's version of the flood story. JEDP: that's the editorial hand; he made it messy; the problem can't be the vocabulary criterion.

3. A criterion for P (no anthropomorphisms) not being valid. JEDP response: I haven't seen any specifically, though I'm betting it would be something like, "well, J and E do *more* anthropomorphizing, so they must be different authors with different religious views." (A "counting noses" answer; the problem can't be the "view of God" criterion — of course this also ignores later anthropomorphosms outside the Pentateuch, and anthropomorphic portrayals in Jewish literature after the biblical period — never mind that stuff).

Beside these specific items, I have alluded to the propensity of JEDP to defend itself by assuming what it seeks to prove, and then offering said assumptions as proof of an argument. In this post I want to illustrate this again from Friedman's second chapter.

Toward the end of Chapter 2, Friedman writes: "J and E were written by two persons . . . the author of J came from Judah and the author of E came from Israel." Friedman believes this difference in location explains differences in the sources, such as the divergence in names for God. Friedman then goes on for a few pages telling readers how items in the text "belong" to a Judah writer and an Israel writer. But stop and think about this: Is he "seeing" these things *because* he already has J and E as sources in his head, or would you just read the Torah through and those things be self evident? I think the former is at play in many respects, and that amounts to assuming what one seeks to prove. Any clever interpreter can come up with some reason why someone living in X location probably wrote this." But is there any compelling reason why someone NOT living in X location could not also have written this? Friedman never considers such things (and, to be fair, he is trying to explain a theory).

At any rate, a number of scholars don't buy the neat picture Friedman creates for the lay reader. For example, there is Rolf Rendtorff, a respected German scholar who says, "The positing of 'sources' in the sense of the documentary hypothesis can no longer make any contribution to understanding the development of the Pentateuch."1 And consider this quotation from The New Oxford Annotated Bible (2007; p. 6).

These are just sample, of course.

My take is that we don't have four sources writers with competing agendas. Rather, there was a Mosaic core, patriarchal traditions that began as oral history, a national history, rules for priests and Levites, and a primeval history section. This sounds a bit like sources, but it's not quite the same. By way of a simplistic summary (this is just a loose description; I haven't systematized this, since I find so many other things more interesting):

1. Israelites before Moses preserve the patriarchal traditions via oral history.

2. The above traditions pre-date arrival in the land, but got written down after Israel arrived at the land (at some point). That is, I don't think Moses was writing them down during the trip, as most conservatives think. He had better, more pressing things to do. I don't think this patriarchal document was written by two writers with competing agendas. I think the patriarchal oral history had "El language" for God since that was the name of God prior to the exodus event. The name of God associated with the exodus (Yahweh) was introduced by God as a way of commemorating the re-creation of the nation (this reflects my agreement with F.M. Cross at Harvard who saw "Yahweh" as meaning "he who causes to be"). Someone who took the Mosaic core (#3 below) and married it to the patriarchal material combined the names in various ways to ensure (and telegraph) theological unity.

3. Moses or someone soon after Moses' death recorded events in Moses' life and leadership period, from the exodus, to Sinai, and through the wilderness. I think the law and Sinai episodes were recorded, along with narration of events as the Israelites traveled. Who knows how much?

4. Parts of the above were included and re-purposed in Deuteronomy. Deuteronomy is therefore a hybrid: parts Mosaic; parts much later adapting Mosaic material and composing new material reflecting occupancy of the land, thereby necessitating adaptations in laws, for example. Same thing for Numbers and Leviticus; the material encompasses times, needs, and customs from the Mosaic period well into the monarchy. Moses, the law, the deliverance from Egypt, and the events at Sinai are constant touchpoints. And so the collective whole is, appropriately, the "law of Moses." I don't care what the percentages are of each hand. And I consider many hands played a role, not just four "source hands."

5. Genesis 1-11 was written during the exile, as it has a Babylonian flavoring in terms of what it seeks to accomplish and respond to theologically (creation epics, flood recounting, Sumerian king list [antediluvian history], Babel. This section gives Israel's rival understanding of the hand of Yahweh in pre-patriarchal history with specific counter-points to Babylon's claims and the claims of other ANE religions (that is, in the process of composing Gen 1-11, the opportunity was taken to take aim at other belief systems / theologies besides that of Babylon).

All the above operated under the hand of Providence, regardless of how many hands and what order things were written. As many of you know, I view inspiration as a providential process, not a (small) series of paranormal events.

In my next and last post, I want to apply the above a bit to statements about the law of Moses in the NT.

R. Rendtorff, Das überlieferungsgeschichtliche Problem des Pentateuch (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 147; Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, 1977), 148. Translation: The tradition-historical problem of the Pentateuch (Supplements to the Journal of the Old Testament scholarship 147; Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, 1977), 148. ↩

Technorati Tags: authorship, Documentary Hypothesis, JEDP, Mosaic, Mosaic law

February 24, 2012

Mosaic Authorship of the Torah: Problems with the Documentary Hypothesis (JEDP), Part 2

I am presuming that most of you have given Friedman's Chapter 2 (from Who Wrote the Bible?) a read-through by now. I wanted to post a couple quick thoughts on why his description, though accurately describing the theory, actually makes me suspicious of the approach. For our purposes here, I'm not going to get into technical rough-and-tumble. Just simple items that, for me, raise red flags as to the coherence of JEDP.

Friedman's Overview

First, Friedman notes that Genesis creation accounts in Gen 1-2 are actually two creation accounts. The bases for this conclusion are:

A different order for creation elements.

Different vocabulary for God (Elohim vs. Yahweh)

He then notes that the same distinction between the names for God is seen in the flood story, and so that story must be two separate stories as well, woven together by someone.

Second, E turns out to be two sources itself as well (E and P). While P also uses "elohim" for the name of God, P has several distinctive markers, namely unique vocabulary that reflects priestly concerns (sacrifice, incense, purity) and shows an interest in dates, numbers, and measurements.

To illustrate how the separate source hypothesis is valid, Friedman proceeds to illustrate J and P comprise the flood story. They can be read separately as coherent stories. The J flood story of course uses Yahweh for the name of God, while P uses Elohim.

Some Inconsistencies

Even at this stage of exposure to the theory a careful reader should notice some inconsistencies. Notice how P features oddly show up in J:

numbers and date calculation (Gen 7:3-4, 10, 12, 17; 8:6, 12) — it's unclear how J has "no concern for dates and numbers" when these verses are assigned to J.

clean and unclean animals (i.e., purity concerns; Gen 7:2; 8:20) – "clean" is an important distinction for sacrifice, which J is not supposed to care about.

My personal favorite among the inconsistencies is harder to detect, since Friedman gives such a small sampling. He insists that J uses anthropomorphic language for God but in P this quality is "virtually entirely lacking" (p. 60). Friedman is actually stronger on this denial of anthropomorphic language in P in his more academic treatment of JEDP in the Anchor Bible Dictionary. In his article on the Torah you'll read this assertion:

"Blatant anthropomorphisms such as God's walking in the garden of Eden (J), making Adam's and Eve's clothes (J), closing Noah's ark (J), smelling Noah's sacrifice (J), wrestling with Jacob (E), standing on the rock at Meribah (E), and being seen by Moses at Sinai/Horeb (J and E) are absent in P." (ABD VI:611, R.E. Friedman).

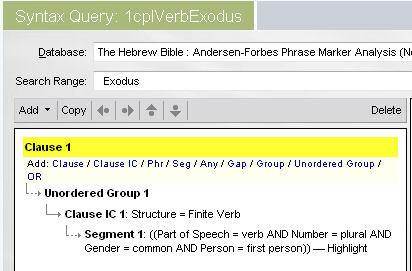

The problem is, Friedman is simply wrong here. It took me about five minutes to come up with the query in the Andersen-Forbes syntax database of the Hebrew Bible to test his assertion (I wrote a paper on this topic a couple years ago for a regional academic meeting). For those who know some Hebrew, here's how my query was formed.

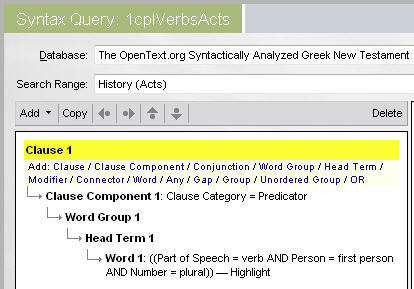

The part of his quotation that struck me as suspicious was his notion that in P the anthropomorphism of being seen (Friedman uses the example of Moses at Sinai, J and E) are absent in P. In the query I asked for all the places in P where a deity is the subject of Hebrew galah and ra'ah in the niphal (both mean "to appear" or "be seen/revealed"). Here's what the search looks like in Logos 4 (note how the Andersen-Forbes syntax database contains searchable source-critical tags (J,E,D,P and others) and searchable tags for noun semantics (Subject: "deity").

The results of the search uncovered clear instances in P of exactly what Friedman says isn't in P. Here is the paper I read at that conference in case readers are interested.

The Point

What we have at this juncture (two posts on JEDP) are some issues that I think significant with respect to the some of the basic ideas that led to the source-critical view of the Pentateuch centuries ago:

1. (First post): Nearly 100 instances where two Hebrew source texts disagree as to the name for God (Yahweh or Elohim). If these textual variations were swapped in and out, there is no doubt the neatness of the name criterion for sources would be marred.

2. P verbiage and concepts showing up in J's version of the flood story.

3. A criterion for P (no anthropomorphisms) not being valid.

Now, lest I be misunderstood, I am not claiming that the above destroys JEDP. That would be greatly overstated. Just because these criteria either fail or are not as neat / coherent as one presumes when reading about the theory doesn't mean the theory is junk. It has other elements. (And we will look at those). What I'm saying is, here are some reasons I don't trust the theory and wonder if there isn't a better way to think about the authorship of the Pentateuch — one that doesn't default to "Moses wrote every word" (something readers know I don't believe either). Maybe Gen 1-2 are the way they are for some other reason — literary, perhaps. Maybe one of the creation accounts is from a different author — but is that justification for seeing it as part of a very large source that runs throughout the Torah? As we'll see, there is a good bit of circular reasoning and extrapolation within the JEDP theory. More reasons to distrust it. I just don't like theories that over-promise and under-deliver.

And in case someone is wondering I did actually bring up some of this stuff in a course while in grad school. Specifically, I asked about the textual differences between MT and LXX with the divine names, and how that might undermine *that* single element of the theory. Believe it or not, the answer I got was "the editor was just sloppy." Seriously? So, we're supposed to breathlessly marvel at the skill of the editor (remember, he was so good it took painstaking work during the 18th and 19th centuries to tease out the sources), but then when there is a problem for justifying the source division we call the same guy a bungling doofus. That's just self-serving illogic, not an answer to the question.

It just doesn't build confidence in the approach. And there's more.

Technorati Tags: anthropomorphism, documentary, E source, elohim, hypothesis, J source, JEDP, Mosaic authorship, P source, Pentateuch, Torah, Yahweh

February 22, 2012

Come to the Pastorum Conference!

Just a heads up.

Logos has organized a conference for June 5-6, 2012 at Park Community Church in Chicago, IL. The event is known as PASTORUM. The conference focus is encouraging pastors and other serious Bible students to engage the text in its original languages and context. There are over twenty well-known scholars speaking, among them: John Walton, Peter Enns, Dan Block, Scot McKnight, Craig Evans, Mark Futato, and Roy Ciampa. I'm also a speaker. You can get $50 off registration if you register before March 10.

Hope you can come!

February 21, 2012

Naked Bible Fantasy Baseball

It's that time of year again … actually, I've only done this for fantasy football in years past — but thought I'd try it for fantasy baseball. Hopefully I'll fare better than fantasy football.

I'm betting that there are a number of baseball fans among the Naked Bible readership (love for baseball and the Naked Bible have both been correlated with high IQ). To that end I've set up a private ESPN league. If you want to play fantasy baseball this year with yours truly and fellow readers, please email me for the league URL and password (mshmichaelsheiser@gmail.com). My team this year: The Hermeneutical Hazards.

It's best if you've played once before, but not a necessity. Here are the main league specs:

LIVE draft: Sunday March 25; 4pm Eastern time

8 teams (so hurry); four teams make the playoffs

Head-to-head league: if you with the majority of the 14 categories, you get a win for that week. The season is 20 weeks.

7 batting categories (AVG, R, RBI, HR, SB, OBP, TB) and 7 pitching categories (W, L, ERA, WHIP, SV, K, QS).

There are 13 starting positions for batters, 5 bench slots, and 2 DL slots.

I'll get back to JEDP (sounds like a stat category) soon.

February 16, 2012

Mosaic Authorship of the Torah: Problems with the Documentary Hypothesis (JEDP), Part 1

In my last several posts on this topic, I have tried to demonstrate via the data of the text of the Hebrew Bible why it is reasonable to argue (from the text) that Moses did not write all or perhaps even most of the Pentateuch (Torah). I have made it clear, though, that I don't buy the consensus view of Mosaic authorship held by nearly all critical scholars, the Documentary Hypothesis. (I'm what used to be called a Supplementarian, but we'll get to that).

For those unfamiliar with this hypothesis, known popularly as the JEDP theory, I was fortunate enough to find a PDF copy of the NY Times bestselling popular book on the subject: R. E. Friedman's, Who Wrote the Bible (it sold over a million copies; we actually had to read this in my doctoral program, too). I would highly recommend reading Chapter 2 of that book to get into the subject along with the Wikipedia link above. In this post and others that follow, I'm going to be explaining why I think the theory over-reaches the data and falls victim to circular reasoning in several instances.

J and E (Yahweh vs. Elohim names for God)

In a nutshell, the JEDP theory posits that Moses didn't write any of the Torah. Rather, the Torah is (in simplest terms) composed of four separate documents, named J, E, D, and P. J and E are named as such because the authors of those alleged sources respectively used Yahweh (J = Jehovah) and Elohim (or other El names) for God. That is, these authors didn't use the other names. When the names are found combined in these respective sources (e.g., Yahweh-Elohim), that is the work of the editor who put the two sources together. Same for where the names are not consistent.

I'm skeptical of the name criterion for determining two of the Torah's presumed sources. One significant reason is that the respective names are not consistent in other texts of the Hebrew Bible. That is, in other texts (namely the Septuagint) the "J" name is in E, and the E name is in J in many places. Friedman dismisses this fact of textual criticism in his Anchor Bible Dictionary article on the Torah:

Though periodically challenged in scholarship, this remains a strong indication of authorship. J excludes the word "God" in narration, with perhaps one or two exceptions out of all the occurrences in the Pentateuch; P maintains its distinction of the divine names with one possible exception in hundreds of occurrences; E maintains the distinction with two possible exceptions. (The LXX and Samaritan Pentateuch have minimal differences from the MT in divine names and have been shown by Skinner to confirm these authorial identifications.)

Friedman claims that there are "minimal differences" from MT (Masoretic Text) and LXX (Septuagint). Really? This isn't the first time I've seen Friedman overstate a case. These days, anyone with the right databases can test this "minimal" claim. So I did. Frankly, I wouldn't call nearly 100 instances minimal (by my quick-and-not-attempting-thoroughness search). You can check the results . Granted, some of the divergences in translation choices in LXX *may* just be the whim of the translator, but it stands to reason (until coherently demonstrated otherwise — and I will get to Skinner's article to which Friedman alluded) that most of these divergences reflect a different text. And that means that the original text of the Torah may not lend itself to the neat divine name criterion JEDP upon which JEDP is (in part, mind you) defended.

As you digest these results and read through Chapter 2 of Friedman's book, I'm guessing other potential reasons for skepticism about the divine name argument for JEDP may become apparent.We'll surely revisit its problems.

Technorati Tags: , documentary, Elohist, JEDP, sources, Yahwist

February 13, 2012

Lexham English Bible Old Testament Now Available

Some readers know that my employer, Logos Bible Software, has been working on a new translation of the Bible for some time. The New Testament of the LEB (Lexham English Bible) has been available since 2010. Logos announced today that the LEB-OT is now available for download. The OT follows the Masoretic Text. The translation has a lot of footnotes as well with respect to literal readings and textual issues. I contributed to the translation (Genesis, 1-2 Chronicles, Micah, Habakkuk, Zephaniah). Check it out!

Technorati Tags: Bible, Lexham English Bible, Logos Bible software, translation

February 6, 2012

The Law of Moses: Does It Read Like Moses Wrote It? Part 2

In my last post on the Mosaic authorship issue, my goal was to produce data from the text that explains why the idea that Moses may not have written all or even most of the Pentateuch could be coherent. I haven't laid out my thoughts on Mosaic authorship yet; I'm just laying the groundwork for establishing the fact that a view that departs from a traditional "Moses wrote everything in the Pentateuch" view can indeed be text-based, even apart from the JEDP (Documentarian) model (which I largely don't buy — we'll eventually get to why).

More specifically, in the last post we saw where Moses was described in the Pentateuch as the subject of a 3rd masc singular verbs ("Moses did XYZ") vs. when the 1st person singular was used, as though Moses himself was writing ("I did XYZ"). The ratio was 7:1, with the 3rd person instances far outnumbering the 1st person. The conclusion was that it is reasonable to suppose that someone other than Moses wrote some of that third person material — i.e., they are not all self-referential. Put more bluntly: Why would Moses use the third person in a self-referential way seven times more often than using the simpler first person to indicate he was the author? I think that's not only a fair question, but it's a good one.

In this post I want to explore person and number a bit more precisely (stop yawning).

Think of the book of Acts. The book is addressed to someone named Theophilus (Acts 1:1), just as the Gospel of Luke (1:3). There is therefore virtually unanimous agreement that Luke was the author of both. However, Luke was apparently only an eyewitness for the events of the book of Acts. This conclusion derives from the fact that he was Paul's traveling companion, as indicated by Paul's notes in Col 4:14; 2 Tim 4:11; and Philemon 24, as well as the author of Acts' use of "'we" when recalling events in Paul's missionary journeys. It is this first person use that draws my attention at this point.

Under the assumption that Luke wrote Acts, one would expect there to be a number of 1st person usages in Acts 13-28, the space devoted to Paul's ministry. If we do a search for the 1st person plural ("we: did XYZ) verb forms in Acts …

… we learn that there are roughly 82 instances in Acts 13-28 (110 overall). Here are the results. However, these 1cpl forms do not all read as though Luke is including himself in the group (e.g., the "we" may refer to conversation in another group Luke is writing about, such as Gentiles or Jews). If one looks through the search results, there are close to 50 instances where the writer uses the 1cpl verb form to include himself. (See the underlined instances in yellow highlighting). So, to put things in general terms, we have 50 good indications in sixteen chapters of Acts that are consistent with Luke as author of the book.

One wonders how many of these we might find in the Pentateuch — a much larger corpus. I decided to look through the books of Exod-Deuteronomy, the books that encompass the lifetime of Moses — and, more specifically, the travels of Israel out of Egypt to Canaan under the leadership of Moses. Here's what the search looked like (I just changed the title of the book in the search range for each search):

The results are interesting. The numbers below represent the total number of occurrences of 1cpl verb forms in these four books — but remember, we'll have to look through all of them to see which ones *specifically* show us the writer (presumably Moses in context) is including himself.

1cpl verb (total) in Exodus: 35

1cpl verb (total) in Leviticus: 3

1cpl verb (total) in Numbers: 64

1cpl verb (total) in Deuteronomy: 59

Here are the results in another PDF. Once again I have gone through them and used yellow highlighting to mark the ones that clearly have the writer including himself in what is being written. Be advised that I exclude instances that are introduced by the THIRD person, as that reads like someone else is writing ABOUT Moses and then has Moses saying something in the first person. What we're looking for is the kind of thing we saw in Acts with Luke — that is what we should expect from a known author's narrative — first person and use of the first person to include himself since he was present. In other words, can we find 1st person self-references that aren't introduced by the third person? I looked through these quickly, so if you want to make an argument for others, let me know.

Cutting to the chase, it was very difficult to find anything like we saw in Luke. It only happens when you get to Deuteronomy, and those are made somewhat questionable by Deut 1:1 (see my notes in the file). A dozen or so.

So, I propose again — in view of the data, it seems reasonable to think that a lot of the Pentateuch was not composed by Moses. For me though (as you will see in the second PDF), there is evidence that suggests an original body of Mosaic first person narrative that was later woven into the larger book of Deuteronomy. And, as I noted at the very beginning of this series, the phrase "law of Moses" need not work only one way (as Moses being the author). The phrase seems entirely appropriate of the Pentateuch (or Exod-Deut) as meaning that the work is about Moses or intimately associated with him, so I don't see any scriptural inconsistency in its use (only our own misuse).

Technorati Tags: authorship, documentary, JEDP, Mosaic, Moses, Torah

Michael S. Heiser's Blog

- Michael S. Heiser's profile

- 921 followers