Michael S. Heiser's Blog, page 76

April 25, 2012

What To Me And To You?

While doing some reverse interlinear work a few days ago, I came across Josh 15:18. The verse concerns Caleb’s newly-won bride:

18 When she came to him, she urged him to ask her father for a field. And she got off her donkey, and Caleb said to her, “What do you want?”

My interest was drawn to the question: “What do you want?” The Hebrew literally reads: “What to you?” This is a fairly common Semiticism that I have run across a number of times before. And each time the idea pops into my head that I ought to write an article on it — since it is the idiomatic expression behind the statement/question Jesus says to his mother Mary in John 2:4. Jesus says, literally, “What to me and to you, O woman?” (“woman” is in the vocative case for direct address.) Many readers mistake the question as a statement of irritation on Jesus’ part, and some translations don’t do much to avoid that misapprehension.

In Josh 15, Caleb is portrayed as wanting to be kind to his new bride. He is not irritated; he wants to do something for her to make her happy. This is the pretty clearly the case in some of the other 18 occurrences of the precise phrase found in Josh 15:18. Some examples (to my eye anyway) are: 2 Sam 14:5; 1 Kings 1:16; Esther 5:3. My point is that the phrase is at times clearly a gentle one.

The similar phrase (“What to me?”) also occurs in the Hebrew Bible, at times in combination with “to you,” as in John 2:4. The most generic way to capture what the full statement (“What to me to you?”) means is “what is there that concerns me and you?” Context should steer the translator to word choices that move the translation from this neutral meaning to something that captures the situation, whether it is adversarial or congenial.

There is no reason to see John’s use of this idiomatic expression as indicative of irritation, or that his mother had become insufferable to Jesus. When Jesus says to Mary, “What to me to you?”, he isn’t saying “What is it now, lady?” He’s basically asking his mother, who brings a concern to him, “What can I do for you?”

Anyway, just a bit of a hobby-horse issue for me that I periodically run into. On to weightier things.

April 21, 2012

Naked Bible Podcast Episode 006 Uploaded

The series on baptism continues. In this episode, I apply my take on getting the circumcision-baptism relationship right to adult and/or believer’s baptism.

Technorati Tags: Baptism, believers, circumcision, infant, podcast

April 19, 2012

James Tabor’s Essay on Early Christianity’s View of Resurrection: A Review

I have to this point confined my thoughts on the “Jesus Family Tomb” (Talpiot A) and the more recent adjacent tomb (Talpiot B) to my PaleoBabble blog, but my thoughts on James Tabor’s recent blog post entitled, “Why People are Confused about the Earliest Christian View of Resurrection of the Dead” seems to fit this blog better. I want readers to know up front that Tabor’s post is quite good — stimulating, thoughtful, irenic in tone — just plain old good stuff for those who enjoy reading biblical studies scholarship.

For those unfamiliar with James Tabor, he is a New Testament scholar and part of the team that has been promoting the Talpiot tomb discoveries. He believes the Talpiot A tomb contained the bones of Jesus, and so he denies the resurrection of Christ as defined as the raising of Jesus’ dead body three days after dying on the cross. But the gist of his article is that ancient Jews and Christians conceived of resurrection as a reconstitution of the dead person in a new body, not a raising of the dead body, making the old body irrelevant. Hence he does not see his view that Jesus’ body was not raised on the third day as a repudiation of the idea of resurrection — and even a physical resurrection at that. Although I think his articulation of this view (as it involves a rejection of the more common view) suffers some coherence problems, I would not want anyone to pass on reading his essay. It’s well worth your time. Readers should digest Tabor’s article first before proceeding.

Lastly, before I proceed, I want to make it clear that what Tabor has produced is intended as a piece of conciliatory scholarship (see the last paragraph). For the record, I think he is entirely sincere in that regard. I have some criticisms of his thinking in what follows, but I want it to be understood that I appreciate what he’s doing here. I just see some coherence problems.

Evaluation

Tabor’s article was a delight to read as he succeeded in bringing out important nuances to how resurrection gets discussed, and how he sees that discussion aligning with, or departing from, primary material in the Old Testament and Hellenistic-Jewish context. He hits his stride about half way, making his contention clear (emphasis mine):

. . . Jews like Jesus, as well as the Pharisees, believed that on the ‘last day,’ the dead would be raised. What people mix up is the literal idea of resuscitation or the ‘standing up’ of a corpse, and the fully developed Jewish idea of resurrection at the end of days. The latter does not involve collecting the dust, the fragmentary decaying bones, or other remains of the body and somehow restoring their form. According to the book of Revelation, even the ‘sea’ gives up the dead that are in it—which can hardly mean one must search for digested bodies that the fish have eaten and eliminated—as unpleasant as the thought may be (Revelation 20:11-15).

Corpse revival is not resurrection of the dead–at least in its classic sense of what happens to all humankind in the end of days. . . . The fully developed view of resurrection of the dead among Jews in the time of Jesus was that at the end of days the dead would come forth from Sheol/Hades—literally the ‘state of being dead,’ and live again in an embodied form.”

The highlighted portions bring into focus where Tabor diverges with what we might call a traditional view of resurrection. He sees incongruity between the Jewish/Judeo-Christian understanding of resurrection and the gospel accounts of the empty tomb because “corpse revival is not resurrection from the dead.” Tabor believes that Jesus’ body was removed from the garden tomb, which was intended as a temporary tomb, and then deposited in what has been called the Talpiot A tomb, where it remained until its discovery in 1980, whereupon all the bones in the tomb were removed and reburied in an unknown location (a practice that is normative in accord with orthodox Jewish wishes when such remains are found). Tabor considers the empty tomb reports in the gospels to have been written post-70 AD, “when the links with the faith of the Jerusalem community had been severed.” In other words, the empty tomb account is, for Tabor and others, in conflict with an original knowledge (and theology) of what happened after the death of Jesus held by the pre-70 AD followers of Jesus. Thus there is a conflict between the beliefs of the original Christians and some of the content of the New Testament.

I don’t follow this thinking since it is problematic in terms of coherence. I offer several items for consideration.

1. The Cart Before the Horse?

At the outset, I would object that one ought not arbitrarily dismiss the empty tomb accounts as late. Tabor would respond that such dismissal is not arbitrary. But I would ask what I think is a reasonable question: Other than the reconstructed theology that results from this division of the material, what empirical data from the text produce that division and the reconstruction? I have read a good deal of NT scholarship that presumes the division, but how do we actually know it is real? Is there something in the grammar or syntax or literary character of these accounts that betray such lateness? If so, I’d like to see it. In the absence of any specifically textual data that produce a pre-/post-70 AD dichotomy to which Tabor adheres, the only conclusion one could draw is that the dichotomy is merely a hermeneutical filter brought to the text. And on one level even if there was textual evidence of lateness it wouldn’t prove the point. Why? Because the fact that X idea wasn’t written about until some point does not prove X idea wasn’t embraced prior to it being written down. This is basic logic. But, in a nutshell, I don’t want a scheme that argues for stripping out the third day empty-tomb resurrection element just because it sounds workable by those who want to dispense with the third day empty-tomb element as part of a larger argument about what happened to Jesus’ body. If that particular element is to be stripped out of the accounting, I want it stripped out by the data of the text, not by virtue of a preconceived filter brought to the text. Coherence in interpretation isn’t based on the beauty of one’s conclusion in one’s own eye (or in collective eyes); it’s based on whether the conclusion actually proceeds from the data. Reconstructive opinion isn’t a substitute for data.

2. Chronological Comment out of the Ether?

Second, Tabor believes Paul’s theology was consistent with the “pre-70 AD reconstitution view” of resurrection which he embraces in his essay (Tabor: “Resurrection of the dead, according to both Paul and Jesus, has nothing to do with the former physical body,” and “Paul knows nothing of that first empty tomb. He knows that Jesus died and was buried and on the third day he was raised up” ). For Paul, Jesus was a “life-giving spirit” (quoting 1 Cor 15:34), and so Paul did not believe that Jesus’ corpse was revived.

But is that all Paul believed about Jesus? Is it impossible that Paul believed in both a corpse revival and a “spiritual body? Many of course would argue just that. But, one could say that, since it’s pretty certain Paul died before 70 AD, his theology could not have drawn from all that post-70 “dead body now standing up” late theology . . . if it’s late . . . right?

This trajectory is related to my first objection, but has tidiness problems of its own.

While it is true that Paul’s writings do not mention the “tomb” of Jesus with respect to his resurrection language, in 1 Cor 15:4 Paul writes that Jesus was buried and raised “on the third day.” A straightforward reading of this phrasing would have Paul’s language of resurrection linked to the “third day” idea that derives from the gospel portions that Tabor says were added after 70 AD. In other words, it seems clear that Paul’s chronological reference to the resurrection derives from the empty tomb description put by all the gospels as occurring on the “first day” of the week subsequent to the dead Jesus being removed from the cross before the beginning of the Sabbath.1 But how can that be if Tabor is correct? If Paul knew nothing of the first empty tomb, whence the third day reference? If we presume the chronological indicators in the gospels about Jesus being raised on the first day of the week after he was put in the tomb before the preceding Sabbath began were absent from any gospel material Paul could have seen to learn about Jesus’ death and burial, where did he get his “third day” chronology? If Paul was thinking only of a future bodily “reconstitution” resurrection “at the last day” subsequent to Jesus’ Talpiot A burial, the chronological reference makes no sense. It seems to me that the gospels are the logical source for Paul’s chronological wording.

But let’s think a bit about how this “third day” information got into Paul’s letter if the gospel material about the third day was post-70. I see two possible answers: (1) Paul got the idea from the OT, not the NT gospels, and so Paul’s statement in 1 Cor 15:4 does not undermine Tabor’s view that the third day material in the gospels is post-70; (2) someone added that language after 70 AD to Paul’s pre-70 letter.

I’ll take the latter first since it’s my guess (and it’s only a guess) that Tabor would choose door number two. It seems akin to what he’s saying about the gospels, so it seems like a good guess. If so, I’d again like to see the empirical textual data for that. It’s a reasonable request. I want data to drive the conclusion, not a presupposed interpretive template.

I looked at several leading commentaries by respected critical NT scholars, all of whom place 1 Corinthians at roughly 50-55 AD, shortly before, and in conjunction with, the composition of Romans, which is dated to the mid-to-late 50s AD. For sure, many struggle with the third day language because they favor the dichotomy Tabor follows. But why? Do these scholars have a reason other than theological preference for finding the phrase in Paul uncomfortable? Without data that is the picture created.

The former alternative — that Paul’s “third day” language derives from the Old Testament (and not the gospels), is adopted by some NT scholars I referenced while reading Tabor’s article. Conzelmann is illustrative. After listing four other speculation-driven options that are offered to defend the lateness of the phrase, he writes (sorry for the imprecision of the transliteration due to Greek font problems): “So there remains a fifth possibility, alongside the first: 5) The date was derived from Scripture. The phrase kata tas graphas “according to the Scriptures,” presumably again refers here, too, not only to egegertai “he was raised,” but to the whole statement. The allusion is indicated in the same general way as that to Isa 53. It can only be to Hos 6:2.”[1. Hans Conzelmann, 1 Corinthians: A Commentary on the First Epistle to the Corinthians (Hermeneia; Fortress Press, 1975), 256.]

This OT source option is a possible choice for Tabor, but I wonder how comfortable he is with it. That a Jew and not a Christian could get a three-day resurrection from the OT undermines his argument elsewhere that certain “resurrection symbology” from Talpiot B (i.e., the “Jonah fish” symbol on an ossuary) is evidence for its identification as a Christian tomb.2

But the OT option has internal problems of its own. The “third day” reference is immediately followed by the reference to Peter seeing the resurrected Christ, and then the twelve — a chronology that proceeds from the gospel chronology involving the third day resurrection. Although appealing to the OT seems a better option, that option has far less explanatory power than just saying Paul got his chronology of events from the gospels, and that means their content was pre-70 AD. Unless Tabor can provide another explanation for Paul’s chronological comment, the notion of this information being added to Paul’s thinking after 70 AD lacks coherence.

Another internal problem for the OT option is probably apparent to readers. If Paul could look at Hosea 6:2 (per Conzelmann above) and perhaps marry it to Jonah 1:17 and Jonah 2:2 (cf. the reference to Sheol), then how is it that the gospel writers could not have done the same thing prior to 70 AD? Why does Paul’s interpretive observation from the OT become unreasonable when the observers and interpreters happen to be a group of Jews who believed Jesus was the messiah, but who were living before 70 AD? On what exegetical, grammatical or syntactical grounds (i.e., grounds that aren’t a theological statement) are we concluding that the third day wording found in the gospels could not have had the same source as that of Paul’s phrasing (and any Jonah fish symbol in Talpiot B)? Again, this strikes me as a very reasonable question.

3. The Either-Or Fallacy

Another coherence problem in Tabor’s articulation is that it presents the reader with an either-or fallacy. Tabor presents his readers with a choice between two options: either embrace the notion that Jews and the original Christians thought of resurrection as a “corpse revival” (the “standing up” of the original, now dead, body) or embrace the fact that Jews and original Christians conceived of resurrection as a remote, future, physicalized re-constitution of the dead person, making the status of anyone’s earthly bones (including those of Jesus) irrelevant to the discussion. There’s actually at least one more option: Jews and early Christians accepted both these notions as resurrection and did not set the two in opposition to each other.

Let’s consider Ezekiel 37:5-6, cited by Tabor in his essay:

“…And I will lay sinews upon you and will cause flesh to come upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and you shall live, and you shall know that I am the LORD.”

Tabor takes this vision of the dry bones as a reconstitution (“Resurrection of the dead here, clearly, is a reconstitution of the physical body”). But I would suggest it is not reconstitution. It simply does not describe or presume the same circumstances as Tabor’s other (better) examples that certainly require reconstitution. What I mean is that, in Ezekiel’s vision, there are bones in the valley, and those same bones become enfleshed and re-animated. The bones are not re-created from dust in the vision (that would be reconstitution). The vision is one of fallen victims whose skeletons lay exposed, or who were perhaps buried (Ezek 37:1). Other examples Tabor notes, or could note, such as bodies lost at sea or immolated bodies, would obviously require reconstitution. But one cannot coherently use Ezek 37 as reconstitution since the bones of the dead are in fact the starting point for the resurrection depiction — just as bones in a grave would be the starting point for a corpse revival resurrection. Tabor apparently (?) presumes that one can only speak of bodily resurrection (i.e., the original body “standing up in corpse revival”) before the flesh has rotted. But on what basis could this view be parsed so precisely? It cannot, and so his categories for resurrection are somewhat contrived, though the nuancing is merited. My view, as noted earlier, is that the Jewish (and Judeo-Christian) view of resurrection included both “standing up” of the old body and reconstitution where that was logically necessitated. I need Tabor to prove that a Jew or early Christian would have rejected one of those before I can begin to see this approach as making sense. I think everyone could agree that there was no uniformity of opinion among Second Temple Judaisms regarding the resurrection, a mode of resurrection, or definition of resurrection. Any argument based on that presumption is tenuous.

4. Servant-King, Corporate and Individual

Another angle to the either-or fallacy presented by Tabor is the incident in Matt 27:51-53, which is seen by many as an allusion to Ezek 37:1-14. This is important since the resurrective events of Matt 27:51-53 are overtly connected to the resurrection of Jesus by the gospel writer.

The above consideration becomes weighty when one factors in some stock elements of OT theology. For an Israelite (and for later Jews wanting a royal deliverer) the anointed king represented the nation. Consequently, the messiah, the ultimate king figure, represented the nation (this individual-to-corporate representation is basic to an OT theology of kingship, and was hardly unique in the ancient Near East). A close reading of Isaiah 40-55 reveals the same thinking about the “servant” in those chapters. The titular servant of God is most often corporate Israel, but is also an individual (most notably, in Isaiah 53). That would mean that anyone associating Isaiah 53 with the messiah (right or wrong — the point is that NT writers did just that) would see the messiah as representing Israel as the servant (and, as noted above, also as king).

So what’s the point? Just this: if the vision of Ezekiel 37 describes the resurrection of the nation of Israel, it could quite easily have been interpreted as being connected to a resurrection of the individual that represented the corporate nation: the servant-king-messiah. And if it is possible to see “standing up corpse revival” in Ezekiel 37 (which is basically described in explicit terms there), that could have fed an expectation or belief that this is what happened to Jesus (for those who saw Jesus fulfilling those roles). These connections are, as I noted above, stick elements of OT and NT theology. There is nothing new here to which I can lay claim.

If the above is the case (that NT writers thought along these lines, or that any Second Temple Jew who knew the Scriptures relatively well) then no one would be surprised at any literary and conceptual connection made between the individuals in Ezekiel’s vision and Matthew 27:51-53 being raised (“stood up” in their original bodies) and the representative of Israel (Jesus as messiah) being raised in the same manner.

5. Front-loading a Question

I want to briefly add a note about the Matthew 27:51-53 episode and include the raising of Lazarus (John 11). One of the reasons Tabor rejects these passages saying anything useful about resurrection is because he presumes (probably correctly, even though the text is silent) that these individuals died (again) later on. Tabor contends that this isn’t the sort of resurrection Jews were expecting has some validity (“What is important to note about all these stories of “resurrection” is that these people returned from death to live again, but they then they subsequently died again”).

The logical problem here concerns how far to press that point. Tabor’s rejection rationale is only valid if the stories reflect the intellectual parsing (on the part of the writers and early Christian readers) Tabor ascribes to them. For Tabor’s objection to have real weight one would have to be sure that there wasn’t a mere point of analogy behind the story (and the episode, for those who assume it happened). That is, while Lazarus and the saints of Matt 27:51-53 were going to die again, how do we know the Jewish writers and readers mostly and exclusively thought “that’s not the sort of thing I’m looking forward to, so that can’t be what my Bible is talking about by resurrection,” and not rather, “this power is a wonderful foretaste of what will happen at the last day, when the kingdom of God comes”? The latter perspective is accompanied by the theological element of the OT that the eschatological kingdom will be an Edenic restoration, a time when there are no more tears due to there being no more death (Isa 25:6-8; 30:19; cp. Hosea 13:14). In other words, there is an “comparing apples and oranges” element to Tabor’s assumption here. He has to assume a certain amount of theological ignorance on the part of the pre-70 Jewish biblical writers. But that hardly seems coherent given the theological-literary output of the Second Temple period, unless one wants to argue the gospel writers had no exposure to that, which would be a hard sell.

Conclusion

I want wrap up by repeating that, despite these criticisms, Tabor’s effort deserves attention and commendation. I wouldn’t have spent the time on it I did if I didn’t believe that. By way of a probably awkward illustration (and I don’t mean any irreverence here), if I died tomorrow and met Jesus in heaven, and he said, “Mike, I’m glad to see you, but I have to tell you that Tabor was right about my resurrection — you see me embodied but I’m really just a life-giving spirit now, preparing to reconstitute all those who believed in what did on the cross, and to be reconstituted myself by my Father when that time comes,” I’m not going to take a rain check or ask Jesus if he’d read this review. Reconstitution the way Tabor describes it would still be a miraculous, gracious act of God, and Tabor’s NT would still have Jesus as the center of that plan. But as things stand now, I’m not persuaded of Tabor’s position.

See Matt 28:1-10; Mark 16:1-8; Luke 24:1-12; John 20:1-10. ↩

See this archive for my posts on the Jonah symbol and related Talpiot B discussion. ↩

Technorati Tags: bones, Christianity, dead, Early, Ezekiel, gospels, Jesus, Jewish, Paul, resurrection, Tabor, tomb

April 14, 2012

Naked Bible Podcast Episode Uploaded

The next episode has been uploaded. I get into the relationship between circumcision and baptism and the need for saying only about baptism what one can say about circumcision. I think this is crucial to the idea of infant baptism being defensible. In the next episode I’ll say a bit about how it relates to believers baptism. Readers and listeners should know by now I have little time for the way infant baptism is articulated in creeds and reformed discussion. It is muddled at best. So, for those whose tradition includes infant baptism, I’m offering a better way to talk about it. I don’t take any position beyond that. The baptism issue for me is close to eschatology on the “whatever” meter, so long as it doesn’t contradict the gospel. The problem is that infant baptism is married to election (incorrectly equated with salvation) and consequently runs contrary to the simple gospel and a doctrine of perseverance (whether reformed theologians want to admit that or not — witness the preceding three podcast episodes). That much I care about.

Technorati Tags: Baptism, circumcision, doctrine, infant baptism, theology

Abortion, Luke 1:15, and Syntactical Databases

A couple months ago a friend sent me a link to a New Testament study that was apparently being popularized within certain segments of the Church to legitimize abortion. The argument is patently illogical, but that isn’t why I’m blogging about it. There’s more to it than just poor thinking. Here we go.

Luke 1:13-15 reads as follows in the ESV:

13 But the angel said to him, “Do not be afraid, Zechariah, for your prayer has been heard, and your wife Elizabeth will bear you a son, and you shall call his name John. 14 And you will have joy and gladness, and many will rejoice at his birth, 15 for he will be great before the Lord. And he must not drink wine or strong drink, and he will be filled with the Holy Spirit, even from his mother’s womb.

Verse 15 is the focus in the argument. The idea is that since John the Baptist was filled with the Holy Spirit from (Greek: ek) his mother’s womb, he only became an actual person when he was born. The “study” connected this language about the Holy Spirit to the breath of life of the first man (Gen 2:7) in arguing this conclusion, and so the thinking was that the birth event evidenced a genuine human life, since birth was the first time the fetus drew breath (or something like that). Now, the logical and theological problems are painfully obvious. To list a few:

1. Why would we presume (biblical, logically, or medically) that every successive human being after Adam received the Holy Spirit when breathing for the first time?

2. Why would we presume that the fetus wasn’t breathing before (i.e., drawing oxygen, which a fetus does do in the womb)?

3. Why would we not conclude, then, that every human born has the Holy Spirit? (I wonder what we get at regeneration then)

It’s easy to pick on; I’ll grant that. But a lot of the discussion focused on the Greek preposition ek (“from”) in Luke 1:15. The author made a big deal that the Holy Spirit (and hence life, and hence human personhood, in this feeble logic trajectory) was only “actual” when the baby left the womb. The preposition nailed things down for the writer. In defense of his view, he quoted the notable modern Greek grammarian Dan Wallace.1 Wallace lists the semantic options for ek as follows:

A. Basic Uses (with Genitive only)

In general, has the force of from, out of, away from, of.

1. Source: out of, from

2. Separation: away from, from

3. Temporal: from, from [this point] … on

4. Cause: because of

5. Partitive (i.e., substituting for a partitive gen.): of

6. Means: by, from

The writer then made the point that ek did not denote a position within the womb or with the mother — but only “out of” or “away from” the mother. And so the fetus only became a human soul/person/recipient of the Spirit once born and “out of” or “away from” the mother.

I want to put aside the numerous ways this interpretation could be demolished and focus on the syntactical force of the preposition ek. There are two approaches we could take in response.

First, it seems this “teacher” presumed Wallace was inspired and didn’t bother to look up the preposition in another reference grammar. For example, A. T. Robertson’s massive reference grammar lists nine possible meanings for the preposition, including place (“The preposition naturally is common with expressions of place. The strict idea of from within is common…”) and origin or source (“Equally obvious seems the use of ek for the idea of origin or source”).2 While the idea of “separation” is of course among Robertson’s options, and would not doubt be favored by our Christian pro-abortion theorist, these options would could easily be referenced, complete with examples, in Robertson’s famous grammar. Wallace is hardly exhaustive (and never pretends to be).

We could reference other grammars to produce the same material, but it’s the second approach that few people would consider that turns out to be even more useful: The Lexham Syntactic Greek New Testament (LSGNT) created by Logos Bible Software through the work of Drs. Albert Lukaszewski, Ted Blakley, and Mark Dubis.

The LSGNT is a database wherein every word of the Greek NT is tagged for its syntactic force in context. It took years of work, primarily by Dr. Lukaszewski, and it’s the perfect tool for something like this issue. I used this tool to answer my friend’s question in regard to the coherence of the view described above. I’ll summarize here.

First, the claim was that the Greek preposition ek not only means “out of, from” in Luke 1:15, thereby denoting that the child only had “the Holy Spirit” (and so, personhood in this logic) once he had exited the womb. Therefore, the child didn’t have the Spirit (and is not a person) while in the womb.

To overturn the claim we would need clear examples where ek indeed does denote “location.” Put another way, we would need to find instances where the preposition does not speak of “distance from” the noun it governs (in Luke 1:15, that would be the womb), but rather “at” or “in” the noun it governs. If we find instances of this usage, the claim is undermined (and then the rules of logic can beat the snot out of it).

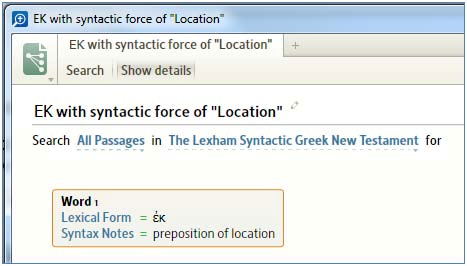

In the LSGNT the search would look like this:

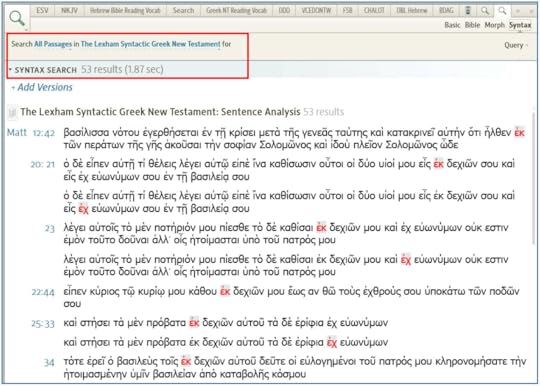

Here’s a screenshot of the results returned by the search (note that ex, epsilon-chi is included as well):

So, according to the scholars who produced the LSGNT, ek/ex has the syntactical force of location 53 times. The next step is naturally to look up the occurrences. A number of them are instances where Jesus is “at (ek) the right hand of God,” for example, which clearly intends to suggest nearness, not distance.

It is telling that Luke 1:15 is in the list of results (not shown in the screen capture). The scholars who created this database saw the preposition ek in that verse as denoting location. We would not choose “at” or “on” for the translation, since either defies common sense – that is, you cannot describe location with respect to a woman’s womb with “at” or “on” precisely because a woman’s womb is inside her body. Hence the best way to translate ek here would be with “in” to denote location. The certainty of this translation is secured by something the our pro-abortion theorist forgot (or never saw): the adverb eti (“still, yet”) immediately preceding the prepositional phrase. The whole phrase, then, is “yet/still in his mother’s womb.” Let me suggest that it makes zero sense to have John the Baptist having the Holy Spirit while still outside his mother’s womb. I’m just saying.

Even more interesting is Acts 14:8, also in the LSGNT result list. It is a word-for-word parallel (minus eti) to Luke 1:15 – “from (ek) his mother’s womb.” The verse in context reads as follows:

8 Now at Lystra there was a man sitting who could not use his feet. He was crippled from birth and had never walked.

Now here is the question: Can we really conclude that this man was only crippled after he had been born? Did the doctor or the midwife drop him? Did he pop out prematurely and hit the ground, incurring a paralyzing injury? I would suggest that his crippling condition could just as well have been congenital, incurred while in (ek) the womb of his mother. It would seem that a congenital condition is actually what is in mind in view of the negative adverb in the description, oudepote, which BDAG defines, “an indefinite negated point of time, never.”3 But I have no reason to believe that the author of the material promoting Luke 1:15 and the preposition ek as support for abortion ever even thought about analyzing all the occurrences of the preposition this way. It’s simply another case of cherry-picking a grammar (usually it’s a lexicon) to “prove” whatever point it is that one favors. Not only is it an exegetical fallacy; it’s an exegetical travesty (sounds like a good book title).

Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics – Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Zondervan Publishing House and Galaxie Software, 1999; 2002), 371. ↩

A.T. Robertson, A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research (Logos, 1919; 2006), 597-598. ↩

William Arndt et al., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (3rd ed.; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 735. ↩

Technorati Tags: abortion, ek, Elizabeth, greek, John the Baptist, Luke 1:15, preposition

April 10, 2012

Of Mustard Seeds and TIME Magazine

We're all familiar with Jesus' statement about faith and the mustard seed. Now there's something else I'm not sure I have enough faith for: Larry Hurtado's post that there's something of a biblical-theological nature worth reading in TIME magazine (on heaven, no less). My doubt muscles are so exercised against the twaddle of popular journalism that even Hurtado's encouragement may not be enough to read the article. But perhaps the flesh will overtake me in the grocery store at the impulse shelf.

April 9, 2012

Baptism as Spiritual Warfare

Over the weekend I had occasion to send a friend some pages from my Myth That is True first draft that pertained to a difficult passage, 1 Peter 3:14-22. I could hardly believe I had not posted on it before (searched for it and came up empty). So, I've decided to include it at some point in the podcast series on baptism. I've actually been present in a church where the pastor, working through 1 Peter, actually announced he was skipping the passage because it was too strange. True, it's weird, but it's actually quite comprehensible against the backdrop of what I call the divine council worldview. So, here it is.

1 Peter 3:14-22

14 But even if you should suffer for righteousness' sake, you will be blessed. Have no fear of them, nor be troubled, 15 but in your hearts regard Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; 16 yet do it with gentleness and respect, having a good conscience, so that, when you are slandered, those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame. 17 For it is better to suffer for doing good, if that should be God's will, than for doing evil. 18 For Christ also suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit, 19 in which he went and proclaimed to the spirits in prison, 20 because they formerly did not obey, when God's patience waited in the days of Noah, while the ark was being prepared, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were brought safely through water. 21 And now the antitype—that is, baptism—saves you, not be means of a removal of dirt from the body, but as an appeal to God for a good conscience on the basis of the resurrection of Jesus Christ, 22 who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers having been subjected to him.

The overall theme of 1 Peter is that Christians must withstand persecution and persevere in their faith. That much is clear in this passage. But what's with baptism, the ark, Noah, and spirits in prison? And does this text say that baptism saves us?

Typology as an Interpretive Key

To understand what's going on in Peter's head here we have to understand a concept that scholars have called "types" or "typology." Typology is a kind of prophecy. We're all familiar with predictive verbal prophecy—when a prophet announces that something is going to come to pass in the future. Sometimes that comes "out of the blue," with God impressing thoughts on the prophet's mind that he utters. On other occasions, a prophet might take an object or perform some act and tell people that the thing or action prefigures something that will happen. Ezekiel was notorious for this, like the time God told him to shave his head and beard, weigh it the balances, and then burn a third of it, beat a third of it with a sword, and scatter the last third to the wind to visually portray the future of the city of Jerusalem (Ezek. 5:1-12). But we only know what Ezekiel's antics meant because they are spelled out in his prophecies. Ezekiel 5 tells us these are prophecies and what the fulfillment would be. Types work differently.

A type is basically an unspoken prophecy. It is an event, person, or institution that foreshadows something that will come, but which isn't revealed until after the fact. For example, in Romans 5:14 Paul tells us that Adam was a tupos of Christ. This Greek word means "kind" or "mark" or "type"—it's actually where "typology" comes from. Paul was saying that, in some way, Adam foreshadowed or echoed something about Jesus. In Adam's case, that something was how his act (sin) had an effect on all humanity. Like Adam, Jesus did something that would have an impact on all humanity—his death and resurrection. Another example would be Passover, since it prefigured the crucifixion of Jesus, who was called "the lamb of God." The point is that there was some analogous connection between the type (Adam) and its echo (Jesus), called the "anti-type" by scholars.

So how does this relate to our weird passage in 1 Peter? Peter uses typology in 1 Peter 3:14–22. Specifically, he assumes that the great flood in Genesis 6-8, especially the sons of God event in Genesis 6:1-4, typify or foreshadow the gospel and the resurrection. For Peter, these events were commemorated during baptism. That needs some unpacking.

Genesis 6 Backdrop

There are tight connections between Genesis 6:1-4 and the epistle of 2 Peter and Jude, whose content mirrors 2 Peter is many ways. Peter and Jude Peter were very familiar with Jewish tradition about Genesis 6 in books like 1 Enoch, and believed them. 1 Enoch 6-15 describes how the sons of God (also called "Watchers") who committed the offense of Genesis 6:1-4 were imprisoned under the earth (the Underworld) for what they had done. The Watchers appealed their sentence and asked Enoch, the biblical prophet who never died (Gen 5:21-24), to intercede for them. 1 Enoch 6:4 puts it this way:

"They [Watchers] asked that I write a memorandum of petition for them, that they might have forgiveness, and that I recite the memorandum of petition for them in the presence of the Lord of heaven."

God sent back his response by way of Enoch, who went to the imprisoned spirits and announced to them that their appeal had been denied (1 Enoch 13:1-3; 14:4-5):

1 "And, Enoch, go and say to Asael, 'You will have no peace.

A great sentence has gone forth against you, to bind you.

2 You will have no relief or petition, because of the unrighteous deeds that you revealed, and because of all the godless deeds and the unrighteousness and the sin that you revealed to men.' "

3 Then I went and spoke to all of them together. And they were all afraid,

and trembling and fear seized them.

1 Enoch goes on to describe the prison term as until the end of days—language that refers to the end times.

2 Peter 2:4 (cp. Jude 6) makes specific reference to the episode of Genesis 6:1-4 and the imprisonment of fallen angels in the Underworld. The incident was also on Peter's mind when he wrote his first epistle—and our strange passage. Peter saw a theological analogy between the events of Genesis 6 and their fallout with the gospel and the resurrection. In other words, he considered these events to be types or precursors to New Testament events and ideas.

Just as Jesus was the second Adam for Paul, Jesus is the second Enoch for Peter. Enoch descended to the imprisoned fallen angels to announce their doom. 1 Pet 3:14–22 has Jesus descending to these same "the spirits in prison," the fallen angels, to tell them they were still defeated, despite his crucifixion. God's plan of salvation and kingdom rule was still intact. In fact, it was right on schedule. The crucifixion actually meant victory over every demonic force opposed to God. This victory declaration is why 1 Pet 3:14–22 ends with Jesus risen from the dead and set at the right hand of God—above all angels, authorities and powers.

Choosing Sides

So how does this relate to baptism? It explains the logic of the passage. Here's the relevant part once more:

18 For Christ also suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit, 19 in which he went and proclaimed to the spirits in prison, 20 because they formerly did not obey, when God's patience waited in the days of Noah, while the ark was being prepared, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were brought safely through water. 21 And now the antitype—that is, baptism—saves you, not be means of a removal of dirt from the body, but as an appeal to God for a good conscience on the basis of the resurrection of Jesus Christ, 22 who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers having been subjected to him.

The two underlined words in verse 21 need reconsideration in light of the divine council worldview. The word most often translated "appeal" (eperotema) in verse 21 is best understood as "pledge" here, a meaning that it has in other material.1 Likewise the word "conscience" (suneidesis) does not refer to the inner voice of right and wrong here as it does elsewhere. Rather, the word refers to "an attitude or decision that reflects one's loyalty," or "conscientiousness," a usage that is also found in other contexts.2

Baptism is not what produces salvation. It "saves" us in that it first involves or reflects a heart decision: a pledge of loyalty to the risen Savior. In effect, baptism in New Testament theology is a loyalty oath, a public avowal of who is on the Lord's side in the cosmic war between good and evil.3 But in addition to that, it is also a visceral reminder to the defeated fallen angels. Every baptism is a reiteration of their doom in the wake of the gospel and the kingdom of God. Early Christians understood the typology of this passage and its link back to the fallen angels of Genesis 6. Early baptismal formulas included a renunciation of Satan and his angels for this very reason.4 Baptism was—and still is—spiritual warfare.

Henry George Liddell et al., A Greek-English Lexicon ("With a revised supplement, 1996"; Rev. and augm. throughout; Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, 1996), 618. ↩

William Arndt et al., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature; 3rd ed.; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 968. ↩

This naturally pertains to adult / believer's baptism, or baptism that has a recipient in view who can make a faith decision. In the case of infant baptism (at least in terms of the biblically-coherent view I describe here for those who want to baptize infants, contra the way it gets "explained" in the reformed creeds, creating theological problems), the idea would be that the "loyalty statement" is made by the parents in their act of baptizing the infant, thus putting it into the community of faith that has the truth — the gospel — which truth must still be believed for salvation. ↩

See here for example. ↩

Technorati Tags: 1 peter 3, ark, Baptism, Enoch, flood, Genesis 6, noah, prison, spirits, typology

April 7, 2012

Latest Episode of the Naked Bible Podcast Series on Baptism

Is now uploaded. Here is the link.

April 5, 2012

Used Books for Biblical Studies

Nope, it's not another Naked Bible book sale extravaganza, but it's close. My colleague at Logos, Doug Mangum (also a fellow graduate student in the UW-Madison's Hebrew department) is selling a few dozen quality books relevant to theology and biblical studies at low prices. Get them while they last!

April 2, 2012

Free Access to ASOR Scholarly Journals – For a Limited Time

Some time ago I blogged on the importance of scholarly journals for biblical research. I also lamented the fact that digital access to these materials is restricted. But now some good news — The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) is making digital access to their scholarly journals available for free for a limited time. Granted, there are only a few journals, and the access is only for the last four years, but you may still find something you'd like to download.

The available journals are:

Near Eastern Archaeology

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research

Journal of Cuneiform Studies

Technorati Tags: academic, biblical, journals, research, scholarly

Michael S. Heiser's Blog

- Michael S. Heiser's profile

- 934 followers