Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 81

April 19, 2016

Interview with Mary Sharratt, author of The Dark Lady's Mask

Today I'm speaking with Mary Sharratt about her newest work of historical fiction, The Dark Lady's Mask: A Novel of Shakespeare's Muse, which delves into the life and times of Aemilia Lanier, England's first professional woman poet, and imagines her relationship with William Shakespeare. I've known Mary for many years through the Historical Novel Society and have spoken with her twice previously for this blog, in 2010 (about

Daughters of the Witching Hill

) and in 2012 (for

Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen

). She always has interesting insights into writing historical fiction, specifically about women's lives. The Dark Lady's Mask is published today (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 416pp, $26 hb/$12.99 ebook).

How did Aemilia Lanier and her work first come to your attention, and later compel you to write a novel about her?

My motto as a historical novelist is “writing women back into history.” I’ve long been frustrated by the fact that the average intelligent, literate person can’t name a woman writer before Jane Austen. The Dark Lady’s Mask is my love letter to literary pioneer Aemilia Bassano Lanier, England’s first professional woman writer. I want to draw her out of the shadows and into the spotlight.

My motto as a historical novelist is “writing women back into history.” I’ve long been frustrated by the fact that the average intelligent, literate person can’t name a woman writer before Jane Austen. The Dark Lady’s Mask is my love letter to literary pioneer Aemilia Bassano Lanier, England’s first professional woman writer. I want to draw her out of the shadows and into the spotlight.

I first discovered her when researching the lives of Renaissance women. The daughter of an Italian court musician who may have been a Marrano, or a secret Jew living under the guise of a Christian convert, Lanier was one of the most highly educated women of her era. She certainly had the talent and expertise to write plays or secular poetry. However in England at that time, the only genre considered acceptable for women was religious verse. Lanier’s female literary predecessors like Mary Sidney wrote poetic meditations on the Psalms.

But Lanier turned the tradition of women’s devotional writing on its head. Her epic poem, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Hail God, King of the Jews), published in 1611, is nothing less than a vindication of the rights of women couched in religious verse. Dedicated and addressed exclusively to women, Salve Deus lays claim to women’s God-given call to rise up against male arrogance, just as the strong women in the Old Testament rose up against their oppressors.

The possibility that Lanier may also have been the mysterious Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s Sonnets only adds to her mystique.

My intention was to write a novel that married the playful comedy of Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard’s Shakespeare in Love to the unflinching feminism of Virginia Woolf’s meditations on Shakespeare’s sister in A Room of One’s Own. How many more obstacles would an educated and gifted Renaissance woman poet face compared with her ambitious male counterpart?

In The Dark Lady’s Mask, I explore what happens when a struggling young Shakespeare meets a struggling young woman poet of equal genius and passion.

In the afterword, you mention the research you did on site in Venice and in Bassano del Grappa. What insights did you take away from your visits there?

My Italian visit was absolutely essential for me in both understanding Aemilia’s character and Shakespeare’s “Italian” plays. Italy was the cultural epicenter of Europe. Shakespeare’s comedies owe a huge debt to the commedia dell’arte. Many of his most popular plays are set in the Veneto region of northern Italy—Aemilia’s ancestral homeland. In Romeo and Juliet, the nurse’s plea, “Give me some aqua vitae,” (Act 3, Scene 2) is a direct reference to the famous strong spirits distilled in Bassano del Grappa, the birthplace of Aemilia’s father. Italy was literally her patrimony.

My novel explores the scenario that Aemilia and Will traveled through Italy together and fell in love.

But, alas, Italy is not all romance. There’s strong circumstantial evidence to suggest that Aemilia’s father and his brothers were banished from their hometown of Bassano because they were Jews. Fleeing to Venice, they assumed the guise of Marranos, or Christian converts, which was an uneasy and not particularly safe existence. Deliverance came in the form of Thomas Seymour, brother to Jane Seymour, that short-lived queen. The highly talented Bassano brothers became royal musicians for King Henry VIII and later for Elizabeth I.

I believe that Aemilia’s double identity as an Italian Jew compelled her to write so boldly in defense of the oppressed. Her Italian background also provided creative female role models that her English sisters lacked. Italian women enjoyed much greater artistic freedoms—they acted on the public stage, unlike in England where boys performed the female roles. Italian women wrote in a wide variety of literary genres. There were even women playwrights, such as the famous and successful Isabella Andreini whose patrons were the Medicis.

You’ve brought a number of historical characters to life in your novels, but William Shakespeare must be the most famous. Did you find it at all daunting to imagine his personality and part of his life on the page?

Daunting doesn’t even begin to describe it! Readers can get very, very contentious when you write fiction about a historical icon like Shakespeare. Because, in essence, writing believable fiction means taking great cultural icons off their pedestals and humanizing them, giving them the same yearnings and foibles as the rest of us mortals. I hope I’ve also made him damn sexy.

Beautifully incorporated into the novel was the possible background to the writing of many of Shakespeare’s plays. Do you have favorites among them?

I adore Shakespeare’s sunlit Italian comedies with their strong, free-spoken heroines. I never get tired of following the adventures of Rosalind in As You Like It, or listening to Beatrice and Benedict spar in Much Ado About Nothing.

For me, as an educator, it was refreshing to read a novel that celebrates not just women’s learning but a humanist education and the value of the liberal arts. Did you have this contemporary resonance in mind as you were writing?

Yes, indeed. I’m very saddened by the funding crisis at your university and the way good teachers in the UK are being pressured to tick government boxes instead of pouring their soul into educating and inspiring their students. In Aemilia’s day, education was the preserve of the elite. Let us not allow it to become so again. The foundation of Western civilization was built on the liberal arts. Yes, vocational training and business studies are important, too, but if we don’t teach our children to love literature, art and theatre, we have only ourselves to blame if they never put down their iphone or read a single unassigned book.

For a good part of the novel, Aemilia’s observations on her environment are those of an outsider, whether she’s either being educated or serving as a teacher in noblewomen’s homes, or when paying a visit to Italian relatives. Did your own experiences living outside your home country inform your writing of Aemilia’s experiences?

Very much so. Being a lifelong expat made me a writer. I left the USA to study in Freiburg, Germany in 1986 and never came back to live permanently in the US. Now I’m a dual US/UK citizen. I will always be an outsider wherever I live—even if I return to the US. I’ve lived abroad so long that I’m forever changed. I believe those who are “foreign” glean insights on a culture that its native born inhabitants might miss—we tend to take the familiar for granted.

As an Anglo-Italian, I’m sure Aemilia felt the same. I imagine she stood out as different and “foreign” wherever she went. Her father’s secret Jewish identity would have weighed on her heart, as well. In my novel, when she visits the Venice Ghetto and disguises herself as a man to go inside a synagogue, she feels even more exiled from her father’s culture and religion when she realizes that she could never truly fit into this world either. Caught between faiths and cultures, she is fated to be eternally betwixt and between.

This is why masks play such a huge role in the novel. Everyone in the book is wearing some kind of metaphorical mask. But because Aemilia is the eternal outsider, she can see through these masks in a way that others can’t.

Religion was a central part of daily life in history, yet this aspect is often neglected in mainstream historical fiction. As was the case with Hildegard von Bingen in Illuminations, I admired how you recreated your characters’ religious lives in a way that makes them feel spiritually rich and authentic to the era yet relevant for modern readers. How did you delve into the religious beliefs of Aemilia as well as her later-in-life mentor, Margaret Clifford?

First of all, thank you very much for the compliment. I agree that it’s impossible to truly get inside the mindset of people who lived before 1900 if you don’t address their religious beliefs as part of their core life experience. But how do you do that without alienating modern, secular readers? It’s a huge challenge, especially for someone like Aemilia. A Jew’s daughter, she was educated by Puritans, lived her life in what was essentially a Protestant police state, and wrote devotional Christian verse. Where did her true spiritual loyalties lie?

Her great friend and literary patron, Margaret Clifford, was an intensely devout Anglican who lived estranged from her abusive husband. She devoted the last years of her life to fighting for her daughter Anne’s inheritance after Anne was disinherited because of her sex, although she was her father’s only child.

Aemilia’s love for Margaret and Anne and her anger at the injustices they faced are the bedrock of her poetry. In Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, she describes the passion of Christ from the viewpoint of the women in the Gospels. In comparing the sufferings of women in male-dominated culture to the sufferings of Christ, she upholds virtuous women as Christ’s true imitators.

Aemilia’s protofeminism is inseparable from her religious sensibilities. Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum is essentially 17th century liberation theology—a corpus of poetry celebrating female and divine goodness, penned by a poet who found her own sense of salvation in a community of women who supported her and believed in her.

How did Aemilia Lanier and her work first come to your attention, and later compel you to write a novel about her?

My motto as a historical novelist is “writing women back into history.” I’ve long been frustrated by the fact that the average intelligent, literate person can’t name a woman writer before Jane Austen. The Dark Lady’s Mask is my love letter to literary pioneer Aemilia Bassano Lanier, England’s first professional woman writer. I want to draw her out of the shadows and into the spotlight.

My motto as a historical novelist is “writing women back into history.” I’ve long been frustrated by the fact that the average intelligent, literate person can’t name a woman writer before Jane Austen. The Dark Lady’s Mask is my love letter to literary pioneer Aemilia Bassano Lanier, England’s first professional woman writer. I want to draw her out of the shadows and into the spotlight.I first discovered her when researching the lives of Renaissance women. The daughter of an Italian court musician who may have been a Marrano, or a secret Jew living under the guise of a Christian convert, Lanier was one of the most highly educated women of her era. She certainly had the talent and expertise to write plays or secular poetry. However in England at that time, the only genre considered acceptable for women was religious verse. Lanier’s female literary predecessors like Mary Sidney wrote poetic meditations on the Psalms.

But Lanier turned the tradition of women’s devotional writing on its head. Her epic poem, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Hail God, King of the Jews), published in 1611, is nothing less than a vindication of the rights of women couched in religious verse. Dedicated and addressed exclusively to women, Salve Deus lays claim to women’s God-given call to rise up against male arrogance, just as the strong women in the Old Testament rose up against their oppressors.

The possibility that Lanier may also have been the mysterious Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s Sonnets only adds to her mystique.

My intention was to write a novel that married the playful comedy of Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard’s Shakespeare in Love to the unflinching feminism of Virginia Woolf’s meditations on Shakespeare’s sister in A Room of One’s Own. How many more obstacles would an educated and gifted Renaissance woman poet face compared with her ambitious male counterpart?

In The Dark Lady’s Mask, I explore what happens when a struggling young Shakespeare meets a struggling young woman poet of equal genius and passion.

In the afterword, you mention the research you did on site in Venice and in Bassano del Grappa. What insights did you take away from your visits there?

My Italian visit was absolutely essential for me in both understanding Aemilia’s character and Shakespeare’s “Italian” plays. Italy was the cultural epicenter of Europe. Shakespeare’s comedies owe a huge debt to the commedia dell’arte. Many of his most popular plays are set in the Veneto region of northern Italy—Aemilia’s ancestral homeland. In Romeo and Juliet, the nurse’s plea, “Give me some aqua vitae,” (Act 3, Scene 2) is a direct reference to the famous strong spirits distilled in Bassano del Grappa, the birthplace of Aemilia’s father. Italy was literally her patrimony.

My novel explores the scenario that Aemilia and Will traveled through Italy together and fell in love.

But, alas, Italy is not all romance. There’s strong circumstantial evidence to suggest that Aemilia’s father and his brothers were banished from their hometown of Bassano because they were Jews. Fleeing to Venice, they assumed the guise of Marranos, or Christian converts, which was an uneasy and not particularly safe existence. Deliverance came in the form of Thomas Seymour, brother to Jane Seymour, that short-lived queen. The highly talented Bassano brothers became royal musicians for King Henry VIII and later for Elizabeth I.

I believe that Aemilia’s double identity as an Italian Jew compelled her to write so boldly in defense of the oppressed. Her Italian background also provided creative female role models that her English sisters lacked. Italian women enjoyed much greater artistic freedoms—they acted on the public stage, unlike in England where boys performed the female roles. Italian women wrote in a wide variety of literary genres. There were even women playwrights, such as the famous and successful Isabella Andreini whose patrons were the Medicis.

You’ve brought a number of historical characters to life in your novels, but William Shakespeare must be the most famous. Did you find it at all daunting to imagine his personality and part of his life on the page?

Daunting doesn’t even begin to describe it! Readers can get very, very contentious when you write fiction about a historical icon like Shakespeare. Because, in essence, writing believable fiction means taking great cultural icons off their pedestals and humanizing them, giving them the same yearnings and foibles as the rest of us mortals. I hope I’ve also made him damn sexy.

Beautifully incorporated into the novel was the possible background to the writing of many of Shakespeare’s plays. Do you have favorites among them?

I adore Shakespeare’s sunlit Italian comedies with their strong, free-spoken heroines. I never get tired of following the adventures of Rosalind in As You Like It, or listening to Beatrice and Benedict spar in Much Ado About Nothing.

For me, as an educator, it was refreshing to read a novel that celebrates not just women’s learning but a humanist education and the value of the liberal arts. Did you have this contemporary resonance in mind as you were writing?

Yes, indeed. I’m very saddened by the funding crisis at your university and the way good teachers in the UK are being pressured to tick government boxes instead of pouring their soul into educating and inspiring their students. In Aemilia’s day, education was the preserve of the elite. Let us not allow it to become so again. The foundation of Western civilization was built on the liberal arts. Yes, vocational training and business studies are important, too, but if we don’t teach our children to love literature, art and theatre, we have only ourselves to blame if they never put down their iphone or read a single unassigned book.

For a good part of the novel, Aemilia’s observations on her environment are those of an outsider, whether she’s either being educated or serving as a teacher in noblewomen’s homes, or when paying a visit to Italian relatives. Did your own experiences living outside your home country inform your writing of Aemilia’s experiences?

Very much so. Being a lifelong expat made me a writer. I left the USA to study in Freiburg, Germany in 1986 and never came back to live permanently in the US. Now I’m a dual US/UK citizen. I will always be an outsider wherever I live—even if I return to the US. I’ve lived abroad so long that I’m forever changed. I believe those who are “foreign” glean insights on a culture that its native born inhabitants might miss—we tend to take the familiar for granted.

As an Anglo-Italian, I’m sure Aemilia felt the same. I imagine she stood out as different and “foreign” wherever she went. Her father’s secret Jewish identity would have weighed on her heart, as well. In my novel, when she visits the Venice Ghetto and disguises herself as a man to go inside a synagogue, she feels even more exiled from her father’s culture and religion when she realizes that she could never truly fit into this world either. Caught between faiths and cultures, she is fated to be eternally betwixt and between.

This is why masks play such a huge role in the novel. Everyone in the book is wearing some kind of metaphorical mask. But because Aemilia is the eternal outsider, she can see through these masks in a way that others can’t.

Religion was a central part of daily life in history, yet this aspect is often neglected in mainstream historical fiction. As was the case with Hildegard von Bingen in Illuminations, I admired how you recreated your characters’ religious lives in a way that makes them feel spiritually rich and authentic to the era yet relevant for modern readers. How did you delve into the religious beliefs of Aemilia as well as her later-in-life mentor, Margaret Clifford?

First of all, thank you very much for the compliment. I agree that it’s impossible to truly get inside the mindset of people who lived before 1900 if you don’t address their religious beliefs as part of their core life experience. But how do you do that without alienating modern, secular readers? It’s a huge challenge, especially for someone like Aemilia. A Jew’s daughter, she was educated by Puritans, lived her life in what was essentially a Protestant police state, and wrote devotional Christian verse. Where did her true spiritual loyalties lie?

Her great friend and literary patron, Margaret Clifford, was an intensely devout Anglican who lived estranged from her abusive husband. She devoted the last years of her life to fighting for her daughter Anne’s inheritance after Anne was disinherited because of her sex, although she was her father’s only child.

Aemilia’s love for Margaret and Anne and her anger at the injustices they faced are the bedrock of her poetry. In Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, she describes the passion of Christ from the viewpoint of the women in the Gospels. In comparing the sufferings of women in male-dominated culture to the sufferings of Christ, she upholds virtuous women as Christ’s true imitators.

Aemilia’s protofeminism is inseparable from her religious sensibilities. Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum is essentially 17th century liberation theology—a corpus of poetry celebrating female and divine goodness, penned by a poet who found her own sense of salvation in a community of women who supported her and believed in her.

Published on April 19, 2016 06:00

April 15, 2016

Book review: The Moon in the Palace, by Weina Dai Randel

Few could guess that the heroine of Weina Dai Randel’s debut novel, young Mei, would emerge into an illustrious future.

Few could guess that the heroine of Weina Dai Randel’s debut novel, young Mei, would emerge into an illustrious future. For readers, there are two hints. In the first few pages, a monk visiting her father, governor of Shanxi Prefecture in China of 631 AD, makes a fabulous prediction about the five-year-old child: that she would “eclipse the light of the sun and shine brighter than the moon… She would mother the emperors of the land but also be emperor in her own name.” The other is in the book’s subtitle: “A Novel of Empress Wu.”

Those unacquainted with the history should avoid googling, since Mei’s path to power is as unusual as it is fascinating to observe. Seven years later, after her father dies under mysterious circumstances, she and her family fall into penury and are forced to move to Chang’an, home of her half-brother, Qing, as well as Emperor Taizong’s glittering palace. By a stroke of luck, her late father’s wish for her is granted, and she’s given a place at the Emperor’s Inner Court as one of his concubines. She hopes to use her status to regain her family's fortunes.

More familiar with Sun Tzu’s The Art of War than delicate embroidery or facial creams, Mei hardly fits in with her fellow maidens, but her acumen brings her to the attention of high-ranking courtiers – as well as enemies who hide their guile behind masks. The many setbacks she encounters, in her quest to become the Emperor’s Most Adored, test her resolve and give her the mental stamina she’ll need for the future.

Far from a standard tale of royal intrigue, The Moon in the Palace provides entrance into a formal yet sumptuous world where the Emperor’s wardrobe is strictly regulated, his amorous pursuits are determined by the "court bedding schedule," and his many ladies are grouped into hierarchies – and Mei sits at the lowest tier.

One of the attractions of novels set in a distant place and era is the different outlook they provide on the world. Randel was born and raised in China and, to create a realistic historical background, conducted research in ancient Chinese texts. She also spices her writing with original, setting-appropriate forms of expression. One prince’s eyebrows “looked as if a calligrapher had lost control when he drew them.” An exclamation of surprise is “Holy ancestors of nine generations!”

There’s also love story, though here, too, but Mei can hardly pursue a romance with Pheasant, a handsome young man who's good with horses, when she’s destined for the Emperor. Or can she? The story is an accessible and expertly plotted introduction to a powerful woman of ancient China, the country's first and only woman to rule as emperor. For those who want to continue Mei’s story, part two (The Empress of Bright Moon) is also newly available.

The Moon in the Palace was published by Sourcebooks in March ($14.99, trade pb, 400pp). Thanks to the publisher for sending me an ARC at my request last fall.

Published on April 15, 2016 07:00

April 11, 2016

The triumph of love: Péter Gárdos' Fever at Dawn

Gárdos’ concise first novel tells an incredibly moving and hopeful love story. The plot dramatizes the unusual real-life circumstances that led the author’s parents to find one another.

Gárdos’ concise first novel tells an incredibly moving and hopeful love story. The plot dramatizes the unusual real-life circumstances that led the author’s parents to find one another.Miklós Gárdos and Lili Reich, both Hungarian concentration-camp survivors, are sent to different rehabilitation hospitals in Sweden following their rescue after WWII. Although Miklós is seriously ill with tuberculosis, and his doctor expects he won’t survive, he refuses to believe this diagnosis, instead choosing to grasp a chance at happiness.

He pens identical letters to the young Hungarian women from his home region who are recuperating in Sweden—all 117 of them, intending to marry one. His letters’ flirtatious tone is delightful, and Miklós receives many replies, but his lively and humorous correspondence with Lili is clearly special.

Both have supportive friends, but some complications ensue. The author also sensitively explores Lili’s religious dilemma, as she feels that her Jewish faith let her down. This is a beautiful tale about two young people joyfully writing a future together when their past is too painful for words.

Péter Gárdos' Fever at Dawn, translated from Hungarian by Elizabeth Szász, is published tomorrow by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt ($23, hardcover, 240pp). This review first appeared in Booklist's March 15th issue.

Read more about the background to this novel in an article from Reuters. "I don’t think this is a Holocaust novel, it’s a story of love," Gárdos says in the interview. "I needed to tell the story of their defiant desire to live, that there’s life after death and how important love was."

A film based on Fever at Dawn, with Gárdos (a renowned film director) directing and co-writing the screenplay, was released last December in Hungary. See the trailer below.

Published on April 11, 2016 17:00

April 8, 2016

Book review: Modern Girls by Jennifer S. Brown, set in NYC's Jewish tenements in the '30s

Set amid the Jewish immigrant community on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1935, Jennifer S. Brown’s engrossing debut novel, Modern Girls, features the intertwined voices of two women, mother and daughter, who both find themselves in the family way. Neither is happy about it.

Set amid the Jewish immigrant community on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1935, Jennifer S. Brown’s engrossing debut novel, Modern Girls, features the intertwined voices of two women, mother and daughter, who both find themselves in the family way. Neither is happy about it. For Rose Krasinsky, worn out from raising five children, a new pregnancy at 42 means her hopes of increased involvement in Socialist activism (and for more time to help rescue her brother, trapped in Europe with his family) must be set aside in favor of more childcare and never-ending housework. And for her 19-year-old daughter, Dottie, finding herself pregnant after an unexpected one-night stand means the end to a promising bookkeeping career – and, most likely, to her future with her longtime boyfriend, Abe.

The author beautifully re-creates the vanished world of Yiddish-speaking immigrants in Depression-era America. (Rose’s husband, Ben/Beryl, shares his name and heritage with my own great-grandfather, which was an added treat; many other family names appeared in the story, too.) The Jewish tenements of 1930s New York are crowded, bustling places where cooking smells spill over into adjacent apartments, Rose’s kosher kitchen ensures her family is properly fed, and residents cart their bedding to their building’s rooftop on muggy summer nights.

Among others who share their background, these characters feel at home, but assimilation into mainstream society isn’t easy even for first-generation Americans. An intelligent career woman, Dottie may be a whiz with numbers, but her status as the only Jew in her workplace doesn’t make her popular with the other gals.

Those seeking insight into the day-to-day lives of women from the last century will find themselves fully involved in the agonizing struggles Rose and Dottie endure as they ponder their choices. Although both live in the modern era, in a modern city, the options for women with an unwanted pregnancy are limited, and it’s not a secret they can keep for very long.

Complicating matters for both is that neither understands the other’s reality. Sacrifices made by Rose, as a young woman in Russia, have shaped her character; she loves her daughter but sees Dottie’s life as luxurious in comparison. Likewise, Dottie can’t imagine that her strict mother could ever comprehend how her situation came about. Through the double narrative, readers can sympathize with both simultaneously. The way each woman handles her dilemma is not resolved predictably – another of the pleasures of reading this warmhearted yet realistic novel – but in looking back, their choices make perfect sense for who they are.

Modern Girls was published by NAL this week ($15.00/C$20.00, trade pb, 363pp). Thanks to the publisher for sending me a review copy at my request.

Published on April 08, 2016 05:00

April 4, 2016

Book review: Death Sits Down to Dinner, by Tessa Arlen

Amid the high-ranking aristocracy of early 20th-century England, investigating a murder isn’t just mentally invigorating and quite possibly dangerous – it’s socially improper. Still, Clementine Talbot, Countess of Montfort, refuses to temper her curiosity.

Events from the first novel in the series, Death of a Dishonorable Gentleman, proved that she and her housekeeper, Mrs. Jackson, made a good sleuthing team, despite the latter’s traditionalist views about crossing class boundaries. Now, when Clementine’s longtime friend Hermione Kingsley hosts a party in honor of Winston Churchill’s 39th birthday, and one of the guests is found face down at the table after dinner, Clementine knows who to ask for help. Even if it means interrupting Mrs. Jackson’s pleasant Christmas holiday in the country and whisking her to London.

Events from the first novel in the series, Death of a Dishonorable Gentleman, proved that she and her housekeeper, Mrs. Jackson, made a good sleuthing team, despite the latter’s traditionalist views about crossing class boundaries. Now, when Clementine’s longtime friend Hermione Kingsley hosts a party in honor of Winston Churchill’s 39th birthday, and one of the guests is found face down at the table after dinner, Clementine knows who to ask for help. Even if it means interrupting Mrs. Jackson’s pleasant Christmas holiday in the country and whisking her to London.

The women’s efforts complement one another, for each can operate within her social circle – that is, upstairs and below – and then compare notes on what they discover. With her paid companion ill and confined to her rooms, Miss Kingsley accepts Mrs. Jackson’s assistance in organizing an event for her favorite charity, a home for orphaned boys. This gives Mrs. Jackson plenty of opportunity to check things out for herself at the murder scene. If, that is, she agrees to join forces with Clementine again.

Solving the “why” is the first puzzle. The victim is a pretentious middle-aged bore, but nobody knows a motive for killing him. Neither does the reader, at first, but Mrs. Jackson, proceeding discreetly, turns up some suspicious goings-on.

The lightness of the tone, and the amusing circumstances the characters find themselves in, counterbalance the serious issues that ground the novel historically. While this entry stands alone, readers continuing from the earlier story will notice a deepening of character development, for Mrs. Jackson in particular. Given her early background, some of the situations she encounters while investigating hold great personal meaning.

Arlen takes care to provide social and political context for her characters’ life choices and behavior. “Underneath the bright chatter at dinner parties,” realizes Clementine, “there was an undercurrent of unease that belied the swaggering conviction that Britain held center stage in world affairs.” As readers of WWI-era fiction know, the times are a-changing. The Montforts’ heir has a passion for flying, which worries them both, and war looms on the horizon, though not everyone foresees it.

And as social barriers start to crumble, the protagonists’ partnership grows stronger. As the novel wraps up, Lord Montfort may still be embarrassed by his wife’s detective talents, but one can guess that if Clementine ever gets the chance to solve another murder, Mrs. Jackson won’t hesitate to join her.

Death Sits Down to Dinner is published by Minotaur this month (hb, 320pp). Thanks to the publisher for providing me with a NetGalley copy. This review is part of the blog tour with HFVBT. See also my review of the first book, Death of a Dishonorable Gentleman .

Events from the first novel in the series, Death of a Dishonorable Gentleman, proved that she and her housekeeper, Mrs. Jackson, made a good sleuthing team, despite the latter’s traditionalist views about crossing class boundaries. Now, when Clementine’s longtime friend Hermione Kingsley hosts a party in honor of Winston Churchill’s 39th birthday, and one of the guests is found face down at the table after dinner, Clementine knows who to ask for help. Even if it means interrupting Mrs. Jackson’s pleasant Christmas holiday in the country and whisking her to London.

Events from the first novel in the series, Death of a Dishonorable Gentleman, proved that she and her housekeeper, Mrs. Jackson, made a good sleuthing team, despite the latter’s traditionalist views about crossing class boundaries. Now, when Clementine’s longtime friend Hermione Kingsley hosts a party in honor of Winston Churchill’s 39th birthday, and one of the guests is found face down at the table after dinner, Clementine knows who to ask for help. Even if it means interrupting Mrs. Jackson’s pleasant Christmas holiday in the country and whisking her to London. The women’s efforts complement one another, for each can operate within her social circle – that is, upstairs and below – and then compare notes on what they discover. With her paid companion ill and confined to her rooms, Miss Kingsley accepts Mrs. Jackson’s assistance in organizing an event for her favorite charity, a home for orphaned boys. This gives Mrs. Jackson plenty of opportunity to check things out for herself at the murder scene. If, that is, she agrees to join forces with Clementine again.

Solving the “why” is the first puzzle. The victim is a pretentious middle-aged bore, but nobody knows a motive for killing him. Neither does the reader, at first, but Mrs. Jackson, proceeding discreetly, turns up some suspicious goings-on.

The lightness of the tone, and the amusing circumstances the characters find themselves in, counterbalance the serious issues that ground the novel historically. While this entry stands alone, readers continuing from the earlier story will notice a deepening of character development, for Mrs. Jackson in particular. Given her early background, some of the situations she encounters while investigating hold great personal meaning.

Arlen takes care to provide social and political context for her characters’ life choices and behavior. “Underneath the bright chatter at dinner parties,” realizes Clementine, “there was an undercurrent of unease that belied the swaggering conviction that Britain held center stage in world affairs.” As readers of WWI-era fiction know, the times are a-changing. The Montforts’ heir has a passion for flying, which worries them both, and war looms on the horizon, though not everyone foresees it.

And as social barriers start to crumble, the protagonists’ partnership grows stronger. As the novel wraps up, Lord Montfort may still be embarrassed by his wife’s detective talents, but one can guess that if Clementine ever gets the chance to solve another murder, Mrs. Jackson won’t hesitate to join her.

Death Sits Down to Dinner is published by Minotaur this month (hb, 320pp). Thanks to the publisher for providing me with a NetGalley copy. This review is part of the blog tour with HFVBT. See also my review of the first book, Death of a Dishonorable Gentleman .

Published on April 04, 2016 05:00

March 31, 2016

Book review: Glory Over Everything: Beyond The Kitchen House, by Kathleen Grissom

By 1830, it’s been 20 years since young Jamie Pyke fled his Virginia plantation home. Now known as James Burton, a respected businessman and ornithologist, he mixes in genteel Philadelphia society. But he holds some dangerous secrets. Despite his fair complexion, his mother was a slave, and he escaped Virginia under violent circumstances.

By 1830, it’s been 20 years since young Jamie Pyke fled his Virginia plantation home. Now known as James Burton, a respected businessman and ornithologist, he mixes in genteel Philadelphia society. But he holds some dangerous secrets. Despite his fair complexion, his mother was a slave, and he escaped Virginia under violent circumstances.When the free black man who once saved James’ life begs a favor—to find his son, Pan, who was kidnapped by slave-traders—James feels obligated to act, even though returning to the South could prove deadly. In addition, his world is already crumbling; his relationship with the woman he loves is at risk.

Grissom’s highly anticipated sequel to The Kitchen House (2010) combines a fast-paced rescue mission and James’ journey toward self-acceptance. Although she occasionally relies on tried-and-true character types, Grissom spins a dramatic story line—the suspense never wavers—and captures the racially tense times. The bravery and unanticipated kindnesses James and Pan encounter in their quests for freedom make this an emotionally rewarding novel. Expect strong book club demand.

Glory Over Everything is published by Simon & Schuster in hardcover next Tuesday ($25.99, 384pp). This review first appeared in Booklist's March 1st issue.

I reviewed The Kitchen House in 2010, and it was one of my favorite reads for that year. While I feel the sequel can stand alone, I felt that it didn't quite offer the same level of originality or character development. Still, a good read, and one that should prove popular. The Kitchen House was a NYT bestseller and book club favorite. Published initially as a trade paperback, it was later republished in a hardback gift edition, and you don't see that a lot.

Published on March 31, 2016 07:27

March 24, 2016

A woman reborn: Goddess of Fire by Bharti Kirchner, set in 17th-century India

Many English-language historical novels set in India take place during the British Raj in the 19th and 20th centuries. Bharti Kirchner’s Goddess of Fire, however, looks further back in time to the mid-17th century, when British and Dutch traders were making early incursions into the Indian economy – which set the stage for later colonial rule.

Many English-language historical novels set in India take place during the British Raj in the 19th and 20th centuries. Bharti Kirchner’s Goddess of Fire, however, looks further back in time to the mid-17th century, when British and Dutch traders were making early incursions into the Indian economy – which set the stage for later colonial rule. The opening scene is tense and dramatic, and it’s based on a real-life incident. Moorti, a well-educated Bengali woman left a widow at age seventeen, is forced by her late husband’s relatives to ascend his funeral pyre in a ritual known as “sati.” After her last-minute rescue by a tall European man named Job Charnock, a trader with the English East India Company, she’s transported to the distant town of Cossimbazar, renamed “Maria,” and installed at his trading station (called a Factory) as a cook.

This forces her into unfamiliar situations, and the novel details her plight as she adjusts to her new role as a servant working among men who, although friendly, don’t share her Brahmin caste or Hindu religion. As she says: “In order to survive, even in my constricted role, I needed to figure out what really went on here, and as I could already understand, proficiency in English was the key to everything.”

An appealing heroine, Maria is a hopeful dreamer who aims to help ease the transition for her people into a future she sees as inevitable. Her increasing fluency in English puts her at the center of conflicts at the Factory and political negotiations. She greatly admires the man she calls “Job sahib,” though knows she has little chance of winning his heart due to her low position and darker skin tone. However, her cleverness and ingenuity lead him to see her in a new perspective.

The romance between the pair (again, historically-based) feels like a sudden development on his part. In addition, although Maria narrates most of the novel in a lively, open voice, occasional segments break away to show Job’s internal thoughts, which seem awkwardly inserted. Still, it’s refreshing to read a novel focusing on this period of Indian history, and which imagines the life of a historical woman about whom little is known. Her culture and traditions come to life beautifully, as do her struggles and triumphs.

Goddess of Fire was published in hardcover by Severn House in February (288pp). Thanks to the publisher for enabling my NetGalley access.

Published on March 24, 2016 07:15

March 18, 2016

Review of Scarpia by Piers Paul Read, a reworking of Puccini's Tosca and its infamous villain

Readers will take away different things from Read’s newest novel, depending on their familiarity with the source material. Newcomers to Puccini’s Tosca will find themselves following a dramatic tale of love, war, honor, and women’s fickleness while learning about the political circumstances of late eighteenth-century Italy, a land where monarchies and Catholicism are threatened by the rising tide of republican thought emanating from revolutionary France. Those with prior knowledge of the opera will also recognize how shrewdly its heartless villain, Baron Scarpia, has been refashioned into a tragic hero.

Readers will take away different things from Read’s newest novel, depending on their familiarity with the source material. Newcomers to Puccini’s Tosca will find themselves following a dramatic tale of love, war, honor, and women’s fickleness while learning about the political circumstances of late eighteenth-century Italy, a land where monarchies and Catholicism are threatened by the rising tide of republican thought emanating from revolutionary France. Those with prior knowledge of the opera will also recognize how shrewdly its heartless villain, Baron Scarpia, has been refashioned into a tragic hero.Vitellio Scarpia is a flawed protagonist, a hotheaded Sicilian adventurer “possessed by the spirit of vendetta.” Following some youthful recklessness, he loses his fortune but later ascends to become a loyal, trusted officer in the pontifical army. Scarpia’s background is richly imagined, and Floria Tosca, a young woman with a glorious singing voice, is mostly a minor character whose story interweaves with his. There are numerous nonfiction digressions from Scarpia’s story, some of which are fairly dry, but they illuminate the context of his turbulent times.

Scarpia was published this month by Bloomsbury USA ($27, hb, 384pp). This review first appeared in Booklist's November 15th issue; I actually read it last September. I'm a reader who wasn't already familiar with Tosca, but I read over a synopsis after finishing this book (not beforehand, as I wanted to avoid spoilers!).

Published on March 18, 2016 12:33

March 14, 2016

An English Rose: an essay by S.K. Rizzolo, author of On a Desert Shore

In today's post, S.K. Rizzolo offers a thought-provoking essay about racial attitudes in early 19th-century English society and the plight of those of mixed race. If you're a fan of the British period film Belle (2013), you'll find her post of particular interest. The 4th and newest volume of Rizzolo's Regency mystery series is On a Desert Shore (Poisoned Pen Press, March 2016).

~

An English Roseby S.K. Rizzolo

Readers of Georgette Heyer’s Regency novels are familiar with her references to skin care products such as Denmark Lotion or Olympian Dew. A young lady’s fair and blooming complexion could be just as critical to her success as her dowry and social position. Then, as now, those with unsightly spots sought to avoid embarrassment. But the ideal of complexion went much deeper than that. It was, in fact, tied to anxieties about Britain’s Empire, notions of proper Englishness, and the desire to maintain boundaries of class and race.

In my novel On a Desert Shore, Marina Garrod receives every advantage of the privileged young lady. Rumored to be the heiress to vast wealth, she debuts in Society with the hope of making an eligible alliance. But to bigoted eyes, there’s a problem. All her father’s money cannot make her into a genuine “English Rose” (pink cheeks and red lips with pale skin)—for Marina is the daughter of a Jamaican planter and his slave-housekeeper. My novel is about Marina’s plight in the England of 1813, a time when attitudes toward race were hardening, in part because of growing fears of cultural and racial contamination.

In my novel On a Desert Shore, Marina Garrod receives every advantage of the privileged young lady. Rumored to be the heiress to vast wealth, she debuts in Society with the hope of making an eligible alliance. But to bigoted eyes, there’s a problem. All her father’s money cannot make her into a genuine “English Rose” (pink cheeks and red lips with pale skin)—for Marina is the daughter of a Jamaican planter and his slave-housekeeper. My novel is about Marina’s plight in the England of 1813, a time when attitudes toward race were hardening, in part because of growing fears of cultural and racial contamination.

Her experience as a mixed-race heiress in Georgian England was not unique. In his dissertation entitled Children of Uncertain Fortune: Mixed Race Migration from the West Indies to Britain, 1750-1820, Dan Livesay estimates that, by the end of the 18th century, as many as a quarter of rich Jamaicans with children of color sent them home to England to live in a free society. On the whole these children were the lucky ones who had escaped the astoundingly brutal and oppressive sugar island. Still, families sometimes challenged the inheritances of their mixed-race kin, and the position of these young people would have been equivocal. It’s difficult to imagine how they might have felt. While Britain had halted its participation in the slave trade in 1807, slavery itself endured for several more decades in the colonies. Apologists for the institution, like Marina’s father, failed to justify a practice that was increasingly seen, according to the poet S.T. Coleridge, as “blotched all over with one leprosy of evil.” Here Coleridge refers to the arguments of West India merchants and slave owners, calling them “cosmetics” designed to conceal a horrible reality.

Deirdre Coleman asserts that the British public of the day had a “fascination with complexion.” And my research revealed that this was especially true of white Creole women (Creole is an ambiguous term that sometimes meant the Blacks of Jamaica and sometimes a person of any race who had spent a lot of time there). I encountered stories of the white Creole women’s attempts to preserve their complexions so that when they returned to England they could seem like legitimate English roses. They wore elaborate sunshades and even flayed their skin with the caustic oil of the cashew nut! Often they created what even some contemporaries called an artificial and unhealthy pallor.

Why? This was a society in which all-powerful white men exploited black women at their own whim and will, a society in which wives were often confronted with the humiliating results of open infidelity—their husbands’ slave children. It was important to the Creole ladies, whose skin could become tanned or weathered in the tropical climate, to maintain strict boundaries through their complexions. In other words, “whiteness” as a marker of status and breeding. But, ironically in this racially mixed society, it might not be possible to determine someone’s precise background just by looking. There might have been little visible difference between a Creole lady and her husband’s mulatta or quadroon concubine.

When a woman named Janet Schaw traveled to North America and the West Indies between 1774-76, she wrote in her diary about putting on and off her delicacy “like any piece of dress.” To me, this points to the performative aspect of femininity. A woman can don a mask of beauty and gentility to further her ends or play her role in society. This is precisely what Marina cannot do to her tormenters’ satisfaction. And yet she is not afraid to express her fellow feeling with African slaves or her contempt for slavery. You will have to read the book to find out what happens after her failed London season. In essence, she is shipwrecked “on a desert shore” in an alien land, even though she is half English and has been mostly reared in England. She is no true English rose.

There’s an unforgettable scene in another novel, an anonymous abolitionist work of 1808 called The Woman of Colour, which introduces Olivia Fairfield, the natural daughter of a West Indian planter and a slave. Like Marina Garrod, Olivia travels to England. In the scene a curious little boy at a tea party compares his hand to Olivia’s, interrogating her about her skin color. Her response: “The same God that made you made me…[as well as my servant Dido, a] poor black woman—the whole world—and every creature in it! A great part of this world is peopled by creatures with skins as black as Dido’s, and as yellow as mine…”

Which leaves us with one of my favorite Shakespearean sonnets, a satiric poem making the point that, after all, what we deem beauty has nothing to do with outward show. After criticizing his beloved for her varied imperfections, including the lack of “roses” in her cheeks, the speaker says: “And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare / As any she belied with false compare.”

The famous portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin, Lady Elizabeth Murray. Belle was the daughter of an enslaved African woman and Sir John Lindsay, a British naval officer. After Lindsay brought his daughter to England, she lived with the Earl of Mansfield, the Lord Chief Justice, at Kenwood House in Hampstead.

The famous portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin, Lady Elizabeth Murray. Belle was the daughter of an enslaved African woman and Sir John Lindsay, a British naval officer. After Lindsay brought his daughter to England, she lived with the Earl of Mansfield, the Lord Chief Justice, at Kenwood House in Hampstead.

Much speculation has arisen in regard to this portrait, whose artist is uncertain. Why does Belle point at her own cheek in a curiously awkward gesture? Perhaps she calls attention to her contrasting complexion in order to suggest that any difference is only “skin deep.” ~

S.K. Rizzolo earned an MA in literature before becoming a high school English teacher and author. Her Regency mystery series features a trio of crime-solving friends: a Bow Street Runner, an unconventional lady, and a melancholic barrister. On a Desert Shore is the fourth title in the series following The Rose in the Wheel, Blood for Blood, and Die I Will Not. Rizzolo lives in Los Angeles.

About On a Desert Shore:

London, 1813: A wealthy West India merchant's daughter is in danger with a vast fortune at stake. Hired to protect the heiress, Bow Street Runner John Chase copes with a bitter inheritance dispute and vicious murder. Meanwhile, his sleuthing partner, abandoned wife Penelope Wolfe, must decide whether Society's censure is too great a bar to a relationship with barrister Edward Buckler. On a Desert Shore stretches from the brutal colony of Jamaica to the prosperity and apparent peace of suburban London. Here a father’s ambition to transplant a child of mixed blood and create an English dynasty will lead to terrible deeds.

~

An English Roseby S.K. Rizzolo

Readers of Georgette Heyer’s Regency novels are familiar with her references to skin care products such as Denmark Lotion or Olympian Dew. A young lady’s fair and blooming complexion could be just as critical to her success as her dowry and social position. Then, as now, those with unsightly spots sought to avoid embarrassment. But the ideal of complexion went much deeper than that. It was, in fact, tied to anxieties about Britain’s Empire, notions of proper Englishness, and the desire to maintain boundaries of class and race.

In my novel On a Desert Shore, Marina Garrod receives every advantage of the privileged young lady. Rumored to be the heiress to vast wealth, she debuts in Society with the hope of making an eligible alliance. But to bigoted eyes, there’s a problem. All her father’s money cannot make her into a genuine “English Rose” (pink cheeks and red lips with pale skin)—for Marina is the daughter of a Jamaican planter and his slave-housekeeper. My novel is about Marina’s plight in the England of 1813, a time when attitudes toward race were hardening, in part because of growing fears of cultural and racial contamination.

In my novel On a Desert Shore, Marina Garrod receives every advantage of the privileged young lady. Rumored to be the heiress to vast wealth, she debuts in Society with the hope of making an eligible alliance. But to bigoted eyes, there’s a problem. All her father’s money cannot make her into a genuine “English Rose” (pink cheeks and red lips with pale skin)—for Marina is the daughter of a Jamaican planter and his slave-housekeeper. My novel is about Marina’s plight in the England of 1813, a time when attitudes toward race were hardening, in part because of growing fears of cultural and racial contamination. Her experience as a mixed-race heiress in Georgian England was not unique. In his dissertation entitled Children of Uncertain Fortune: Mixed Race Migration from the West Indies to Britain, 1750-1820, Dan Livesay estimates that, by the end of the 18th century, as many as a quarter of rich Jamaicans with children of color sent them home to England to live in a free society. On the whole these children were the lucky ones who had escaped the astoundingly brutal and oppressive sugar island. Still, families sometimes challenged the inheritances of their mixed-race kin, and the position of these young people would have been equivocal. It’s difficult to imagine how they might have felt. While Britain had halted its participation in the slave trade in 1807, slavery itself endured for several more decades in the colonies. Apologists for the institution, like Marina’s father, failed to justify a practice that was increasingly seen, according to the poet S.T. Coleridge, as “blotched all over with one leprosy of evil.” Here Coleridge refers to the arguments of West India merchants and slave owners, calling them “cosmetics” designed to conceal a horrible reality.

Deirdre Coleman asserts that the British public of the day had a “fascination with complexion.” And my research revealed that this was especially true of white Creole women (Creole is an ambiguous term that sometimes meant the Blacks of Jamaica and sometimes a person of any race who had spent a lot of time there). I encountered stories of the white Creole women’s attempts to preserve their complexions so that when they returned to England they could seem like legitimate English roses. They wore elaborate sunshades and even flayed their skin with the caustic oil of the cashew nut! Often they created what even some contemporaries called an artificial and unhealthy pallor.

Why? This was a society in which all-powerful white men exploited black women at their own whim and will, a society in which wives were often confronted with the humiliating results of open infidelity—their husbands’ slave children. It was important to the Creole ladies, whose skin could become tanned or weathered in the tropical climate, to maintain strict boundaries through their complexions. In other words, “whiteness” as a marker of status and breeding. But, ironically in this racially mixed society, it might not be possible to determine someone’s precise background just by looking. There might have been little visible difference between a Creole lady and her husband’s mulatta or quadroon concubine.

When a woman named Janet Schaw traveled to North America and the West Indies between 1774-76, she wrote in her diary about putting on and off her delicacy “like any piece of dress.” To me, this points to the performative aspect of femininity. A woman can don a mask of beauty and gentility to further her ends or play her role in society. This is precisely what Marina cannot do to her tormenters’ satisfaction. And yet she is not afraid to express her fellow feeling with African slaves or her contempt for slavery. You will have to read the book to find out what happens after her failed London season. In essence, she is shipwrecked “on a desert shore” in an alien land, even though she is half English and has been mostly reared in England. She is no true English rose.

There’s an unforgettable scene in another novel, an anonymous abolitionist work of 1808 called The Woman of Colour, which introduces Olivia Fairfield, the natural daughter of a West Indian planter and a slave. Like Marina Garrod, Olivia travels to England. In the scene a curious little boy at a tea party compares his hand to Olivia’s, interrogating her about her skin color. Her response: “The same God that made you made me…[as well as my servant Dido, a] poor black woman—the whole world—and every creature in it! A great part of this world is peopled by creatures with skins as black as Dido’s, and as yellow as mine…”

Which leaves us with one of my favorite Shakespearean sonnets, a satiric poem making the point that, after all, what we deem beauty has nothing to do with outward show. After criticizing his beloved for her varied imperfections, including the lack of “roses” in her cheeks, the speaker says: “And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare / As any she belied with false compare.”

The famous portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin, Lady Elizabeth Murray. Belle was the daughter of an enslaved African woman and Sir John Lindsay, a British naval officer. After Lindsay brought his daughter to England, she lived with the Earl of Mansfield, the Lord Chief Justice, at Kenwood House in Hampstead.

The famous portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin, Lady Elizabeth Murray. Belle was the daughter of an enslaved African woman and Sir John Lindsay, a British naval officer. After Lindsay brought his daughter to England, she lived with the Earl of Mansfield, the Lord Chief Justice, at Kenwood House in Hampstead. Much speculation has arisen in regard to this portrait, whose artist is uncertain. Why does Belle point at her own cheek in a curiously awkward gesture? Perhaps she calls attention to her contrasting complexion in order to suggest that any difference is only “skin deep.” ~

S.K. Rizzolo earned an MA in literature before becoming a high school English teacher and author. Her Regency mystery series features a trio of crime-solving friends: a Bow Street Runner, an unconventional lady, and a melancholic barrister. On a Desert Shore is the fourth title in the series following The Rose in the Wheel, Blood for Blood, and Die I Will Not. Rizzolo lives in Los Angeles.

About On a Desert Shore:

London, 1813: A wealthy West India merchant's daughter is in danger with a vast fortune at stake. Hired to protect the heiress, Bow Street Runner John Chase copes with a bitter inheritance dispute and vicious murder. Meanwhile, his sleuthing partner, abandoned wife Penelope Wolfe, must decide whether Society's censure is too great a bar to a relationship with barrister Edward Buckler. On a Desert Shore stretches from the brutal colony of Jamaica to the prosperity and apparent peace of suburban London. Here a father’s ambition to transplant a child of mixed blood and create an English dynasty will lead to terrible deeds.

Published on March 14, 2016 06:00

March 9, 2016

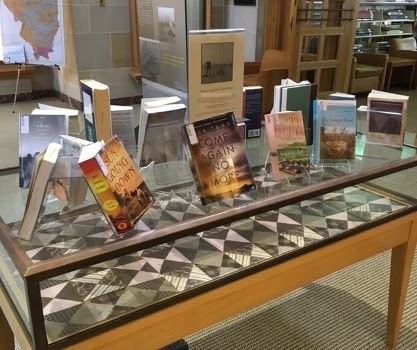

Two library displays: the Dust Bowl and Downton Abbey

Historical fiction has been getting a nice showing at my library. I recently put together a couple of book displays: one on fiction about the Dust Bowl, to accompany a national traveling exhibition and program series that we'd hosted ("Dust, Drought, and Dreams Gone Dry"), and another to provide reading suggestions for Downton Abbey fans after Sunday's finale (sob!).

These are two separate exhibits, in different parts of the building, although books from one have occasionally migrated to the other.

I'd previously written up a post on an earlier Downton-themed display in April 2014. This new one has many of the same titles, plus some more recent publications. It's been going fairly well; although the display isn't quite as popular as last time, about 1/4 of the books were checked out in the first couple of days.

For anyone interested in seeing lists of titles included in both displays, along with book cover images and links to publisher blurbs, they're online at my library's website: Dust Bowl Fiction and Downton Abbey Display.

And! I have a new image at the top of the blog, a photo of Bamburgh Castle in Northumberland, taken during our visit there in September 2014. An early name for Bamburgh was Bebbanburg, which fans of Bernard Cornwell's Saxon novels will recognize as the home of Uhtred. Check out my husband's Flickr page for more dramatic pics of Bamburgh.

These are two separate exhibits, in different parts of the building, although books from one have occasionally migrated to the other.

I'd previously written up a post on an earlier Downton-themed display in April 2014. This new one has many of the same titles, plus some more recent publications. It's been going fairly well; although the display isn't quite as popular as last time, about 1/4 of the books were checked out in the first couple of days.

For anyone interested in seeing lists of titles included in both displays, along with book cover images and links to publisher blurbs, they're online at my library's website: Dust Bowl Fiction and Downton Abbey Display.

And! I have a new image at the top of the blog, a photo of Bamburgh Castle in Northumberland, taken during our visit there in September 2014. An early name for Bamburgh was Bebbanburg, which fans of Bernard Cornwell's Saxon novels will recognize as the home of Uhtred. Check out my husband's Flickr page for more dramatic pics of Bamburgh.

Published on March 09, 2016 17:00