Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 80

May 21, 2016

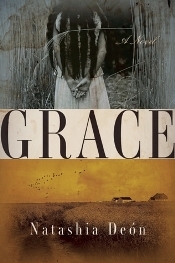

Grace by Natashia Deón, an affecting novel of freedom and motherhood in the antebellum South

Given the chance, Naomi, a 17-year-old slave in rural Alabama in 1848, would have named her daughter Grace, but she is shot and killed moments after giving birth. In her gripping debut novel, Deón, awarded a PEN Center USA Emerging Voices Fellowship, among other honors, dramatizes alliances formed by women in a violent place and time with adroit characterizations, a powerful narrative voice, and the propulsive plotting of a suspense novel.

Given the chance, Naomi, a 17-year-old slave in rural Alabama in 1848, would have named her daughter Grace, but she is shot and killed moments after giving birth. In her gripping debut novel, Deón, awarded a PEN Center USA Emerging Voices Fellowship, among other honors, dramatizes alliances formed by women in a violent place and time with adroit characterizations, a powerful narrative voice, and the propulsive plotting of a suspense novel.Kept lingering in the afterlife through her love for her daughter, Josey, Naomi tells the story in two intertwined strands. One traces her earlier life via flashbacks, covering her flight to Georgia after a deadly confrontation, her rescue by a female brothel owner with her own secretive past, and her falling in love with a white gambler. In the other, Naomi follows blonde, light-skinned Josey as she grows up before, during, and after emancipation, which hardly brings the liberty the former slaves hope for.

Naomi’s unique situation is movingly evoked: she offers Josey tender maternal advice, which goes unheard, and is unable to protect her from painful realities. Deón stays in control of her complex material, from its clever parallel structure to the women’s psychological reactions to relentless tension. Readers will ache for these strong characters and yearn for them to find freedom and peace.

Grace is officially published by Counterpoint in June (hardcover, $25, 400pp), but Amazon has copies in stock now. This starred review first appeared in Booklist's April 15th issue. I was pleased to see, later on, that Kirkus and Publishers Weekly had also published starred reviews. This is a book that has important things to say about the American past, and it deserves widespread attention.

Published on May 21, 2016 05:00

May 17, 2016

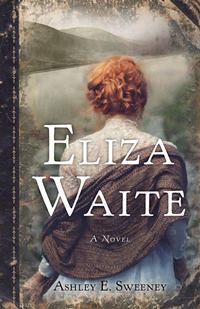

Accuracy in historical fiction: a guest post by Ashley Sweeney, author of Eliza Waite

In today's guest post, author Ashley Sweeney expands upon a topic familiar to historical fiction writers and readers: getting the facts right. I'll be posting a review of her debut novel, Eliza Waite, in the near future.

~

Accuracy in Historical FictionAshley Sweeney

In children’s literature, if a frog and a monkey wear striped pajamas and go on vacation to the moon, we think nothing of it. But give Jean Valjean a cellphone or Jane Eyre a Corvette and poof! Our credibility’s shot.

author Ashley Sweeney

author Ashley Sweeney

(credit: Karen Mullen Photography)Back when I was a newbie reporter at a rural weekly newspaper, the Five W’s: Who/What/When/Where/Why ruled first paragraphs. The thinking behind a formulaic style of writing is that if stories must be shortened due to space limitations, all the facts still appear in the story.

And our editor drilled into our heads: Check your facts. And you better get them right. Period.

In literature, authors have the luxury of spreading out details, at times feeding them crumb-by-crumb to readers. All elements are not weighed equally. In character-driven plots, Who or What is vital. In murder mysteries, Why, and its partner How, reigns. Historical fiction draws heavily on Where and When; setting identifies time, place, and mood of the narrative.

And what’s paramount for authors of historical fiction: we can’t make mistakes. We have to check our facts and get them right. Period.

In writing Eliza Waite, I was constantly fact-checking myself. Did matchsticks exist in the late 19th century? Who was president of the U.S. in 1890s? What was the major source of news in the San Juan Islands and Skagway, Alaska at the turn of the last century?

Where did women go for female hysteria treatments? When was The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde published? Why did tens of thousands of men and women drop out of their lives to search for elusive gold in the Klondike?

And how did women cook and bake without any modern conveniences?

I amassed more than 100 books on various subjects pertinent to the era and turned to librarians, historians, museum curators, authors, and storytellers to fill in holes. Of course the Internet was a constant companion.

I encountered surprises while researching, including the fact that Skagway was electrified before most of the United States. A.F. Eastman founded Skagway Electric Light Company in the fall of 1897. Within months, Alaska Electric Light and Power Company, which traced its roots to 1893 Juneau, appeared in Skagway in competition. By the summer of 1898 at the height of the Klondike Gold Rush, the companies dueled for customers and Skagway’s streetlights, hotels, and businesses were illuminated.

I encountered surprises while researching, including the fact that Skagway was electrified before most of the United States. A.F. Eastman founded Skagway Electric Light Company in the fall of 1897. Within months, Alaska Electric Light and Power Company, which traced its roots to 1893 Juneau, appeared in Skagway in competition. By the summer of 1898 at the height of the Klondike Gold Rush, the companies dueled for customers and Skagway’s streetlights, hotels, and businesses were illuminated.

The fact that Skagway was electrified allowed my protagonist—a baker at Skagway’s The Moonstone Café—to marvel over the new-fangled invention.

What wonders will this new electric invention open up? It won’t be long before kitchens are electrified! Electric lights! Electric mixers! Maybe even electric ovens!

But imagine if I had my protagonist driving a Jeep or arriving in Alaska by air in 1898 rather than by steamship from Seattle. I’d certainly get bad reviews or be booted out of historical novel associations. Or worse. I might be tarred and feathered. Or—heaven forbid!—put in the stocks.

Ashley Sweeney is the author of Eliza Waite, published in May 2016 by She Writes Press.

~

Accuracy in Historical FictionAshley Sweeney

In children’s literature, if a frog and a monkey wear striped pajamas and go on vacation to the moon, we think nothing of it. But give Jean Valjean a cellphone or Jane Eyre a Corvette and poof! Our credibility’s shot.

author Ashley Sweeney

author Ashley Sweeney(credit: Karen Mullen Photography)Back when I was a newbie reporter at a rural weekly newspaper, the Five W’s: Who/What/When/Where/Why ruled first paragraphs. The thinking behind a formulaic style of writing is that if stories must be shortened due to space limitations, all the facts still appear in the story.

And our editor drilled into our heads: Check your facts. And you better get them right. Period.

In literature, authors have the luxury of spreading out details, at times feeding them crumb-by-crumb to readers. All elements are not weighed equally. In character-driven plots, Who or What is vital. In murder mysteries, Why, and its partner How, reigns. Historical fiction draws heavily on Where and When; setting identifies time, place, and mood of the narrative.

And what’s paramount for authors of historical fiction: we can’t make mistakes. We have to check our facts and get them right. Period.

In writing Eliza Waite, I was constantly fact-checking myself. Did matchsticks exist in the late 19th century? Who was president of the U.S. in 1890s? What was the major source of news in the San Juan Islands and Skagway, Alaska at the turn of the last century?

Where did women go for female hysteria treatments? When was The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde published? Why did tens of thousands of men and women drop out of their lives to search for elusive gold in the Klondike?

And how did women cook and bake without any modern conveniences?

I amassed more than 100 books on various subjects pertinent to the era and turned to librarians, historians, museum curators, authors, and storytellers to fill in holes. Of course the Internet was a constant companion.

I encountered surprises while researching, including the fact that Skagway was electrified before most of the United States. A.F. Eastman founded Skagway Electric Light Company in the fall of 1897. Within months, Alaska Electric Light and Power Company, which traced its roots to 1893 Juneau, appeared in Skagway in competition. By the summer of 1898 at the height of the Klondike Gold Rush, the companies dueled for customers and Skagway’s streetlights, hotels, and businesses were illuminated.

I encountered surprises while researching, including the fact that Skagway was electrified before most of the United States. A.F. Eastman founded Skagway Electric Light Company in the fall of 1897. Within months, Alaska Electric Light and Power Company, which traced its roots to 1893 Juneau, appeared in Skagway in competition. By the summer of 1898 at the height of the Klondike Gold Rush, the companies dueled for customers and Skagway’s streetlights, hotels, and businesses were illuminated. The fact that Skagway was electrified allowed my protagonist—a baker at Skagway’s The Moonstone Café—to marvel over the new-fangled invention.

What wonders will this new electric invention open up? It won’t be long before kitchens are electrified! Electric lights! Electric mixers! Maybe even electric ovens!

But imagine if I had my protagonist driving a Jeep or arriving in Alaska by air in 1898 rather than by steamship from Seattle. I’d certainly get bad reviews or be booted out of historical novel associations. Or worse. I might be tarred and feathered. Or—heaven forbid!—put in the stocks.

Ashley Sweeney is the author of Eliza Waite, published in May 2016 by She Writes Press.

Published on May 17, 2016 06:30

May 15, 2016

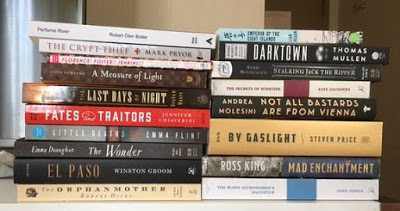

Reporting back on the historical fiction at #BEA2016 in Chicago

I'm just back from BEA in Chicago, which was convenient for me; it's a 3-hour drive, so it didn't involve the usual flight and mailing of books back home. I had a good time and met up with many friends, librarian colleagues, publisher contacts, and my editor at Booklist. However, the show was noticeably smaller. Many publishers, both large and small, decided not to exhibit this year, and the level of energy didn't seem as high. Some of the booths felt cramped, with little room to move around if someone else was there browsing. These days, having a BEA outside of NYC has its consequences.

I went representing the Historical Novels Review and picked up a number of galleys (and some finished books) that will end up in reviewers' hands. Others, the signed copies in particular, I got just for me! Because I had a plan of which historical novels would be available when, I did my best to stick to it and mostly succeeded, although I didn't make it to events late in the day. Standing on carpeted concrete for an entire day doesn't agree with my back, and by mid-afternoon, I was exhausted.

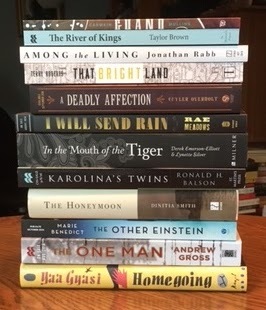

Here are some piles that I brought back with me. Rather than repeat myself, I'll link back to the guide to historical novels at BEA 2016 because blurbs for the majority can be found there. There were some nice surprises, too, books I didn't expect would be there. Details below on those.

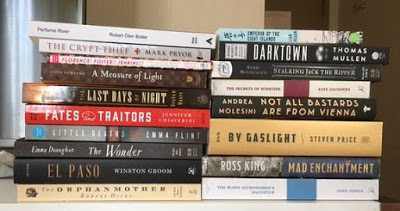

Beth Powning's A Measure of Light (Penguin Canada, March) is biographical fiction about 17th-century Quaker Mary Dyer, who repeatedly defied Puritan authorities.

Kerri Maniscalco's Stalking Jack the Ripper is YA gothic horror, about a lord's daughter with an interest in forensic medicine. It's out in Sept. from Jimmy Patterson, James Patterson's new children's imprint with Hachette.

These aren't historical fiction but looked interesting: The Crypt Thief by Mark Pryor is a crime novel set in modern-day Paris, and Robert Olen Butler's Perfume River deals with the aftermath of Vietnam. Daryl W. Bullock's Florence Foster-Jenkins (Overlook) is nonfiction about the world's worst singer, soon to be portrayed in film by Meryl Streep. Mad Enchantment by Ross King is nonfiction about Monet's painting of the water lilies toward the end of his life.

In this pile, Louis Carmain's Guano (Coach House, Oct. 2015) is a novel about Peruvian independence and lustful adventures in the year 1862.

Taylor Brown's The River of Kings (St. Martin's, March 2017), which was a nice find since it isn't on Amazon yet, is set around the area of Fort Caroline, an early French settlement in 16th century Florida, both centuries ago and in modern periods.

Terry Roberts' That Bright Land (Turner, June) is described as a "southern Gothic thriller" set during the Civil War.

In the Mouth of the Tiger by Derek Emerson-Elliott and Lynette Silver (Sally Milner Publishing, Feb 2015) isn't one I'd come across before. It's about a young Russian woman's adventures in Singapore and Malaya around the WWII years. The publisher is Australian.

And Dinitia Smith's The Honeymoon delves into George Eliot's surprising later-in-life marriage and subsequent honeymoon in 1880 Venice.

I picked up some of these at the Friday afternoon speed dating session for librarians, booksellers, and book group leaders, and it was my 3rd year attending this session. It's one of my favorite events of the show, so I'm kind of upset that I mistakenly left the handout on the table. Hopefully it will be posted later.

Seeing all these piles, and having some deadlines looming, I'd better get back to reading.

I went representing the Historical Novels Review and picked up a number of galleys (and some finished books) that will end up in reviewers' hands. Others, the signed copies in particular, I got just for me! Because I had a plan of which historical novels would be available when, I did my best to stick to it and mostly succeeded, although I didn't make it to events late in the day. Standing on carpeted concrete for an entire day doesn't agree with my back, and by mid-afternoon, I was exhausted.

Here are some piles that I brought back with me. Rather than repeat myself, I'll link back to the guide to historical novels at BEA 2016 because blurbs for the majority can be found there. There were some nice surprises, too, books I didn't expect would be there. Details below on those.

Beth Powning's A Measure of Light (Penguin Canada, March) is biographical fiction about 17th-century Quaker Mary Dyer, who repeatedly defied Puritan authorities.

Kerri Maniscalco's Stalking Jack the Ripper is YA gothic horror, about a lord's daughter with an interest in forensic medicine. It's out in Sept. from Jimmy Patterson, James Patterson's new children's imprint with Hachette.

These aren't historical fiction but looked interesting: The Crypt Thief by Mark Pryor is a crime novel set in modern-day Paris, and Robert Olen Butler's Perfume River deals with the aftermath of Vietnam. Daryl W. Bullock's Florence Foster-Jenkins (Overlook) is nonfiction about the world's worst singer, soon to be portrayed in film by Meryl Streep. Mad Enchantment by Ross King is nonfiction about Monet's painting of the water lilies toward the end of his life.

In this pile, Louis Carmain's Guano (Coach House, Oct. 2015) is a novel about Peruvian independence and lustful adventures in the year 1862.

Taylor Brown's The River of Kings (St. Martin's, March 2017), which was a nice find since it isn't on Amazon yet, is set around the area of Fort Caroline, an early French settlement in 16th century Florida, both centuries ago and in modern periods.

Terry Roberts' That Bright Land (Turner, June) is described as a "southern Gothic thriller" set during the Civil War.

In the Mouth of the Tiger by Derek Emerson-Elliott and Lynette Silver (Sally Milner Publishing, Feb 2015) isn't one I'd come across before. It's about a young Russian woman's adventures in Singapore and Malaya around the WWII years. The publisher is Australian.

And Dinitia Smith's The Honeymoon delves into George Eliot's surprising later-in-life marriage and subsequent honeymoon in 1880 Venice.

I picked up some of these at the Friday afternoon speed dating session for librarians, booksellers, and book group leaders, and it was my 3rd year attending this session. It's one of my favorite events of the show, so I'm kind of upset that I mistakenly left the handout on the table. Hopefully it will be posted later.

Seeing all these piles, and having some deadlines looming, I'd better get back to reading.

Published on May 15, 2016 06:30

May 12, 2016

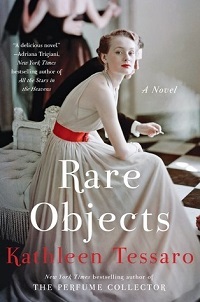

Ambition and deception: Rare Objects by Kathleen Tessaro, set in Depression-era Boston

Maeve Fanning, an educated young Irish American in Depression-era Boston, wants to move forward in life, and aims high. When she gets wind of a sales job at an exclusive antique shop, she bleaches her red tresses to disguise her heritage, calls herself May (“with a y”), and finagles her way into the position. There, under the guidance of the store’s English co-owner, who appreciates her ingenuity, she learns how to gear her pitch to its eccentric, wealthy customers.

Maeve Fanning, an educated young Irish American in Depression-era Boston, wants to move forward in life, and aims high. When she gets wind of a sales job at an exclusive antique shop, she bleaches her red tresses to disguise her heritage, calls herself May (“with a y”), and finagles her way into the position. There, under the guidance of the store’s English co-owner, who appreciates her ingenuity, she learns how to gear her pitch to its eccentric, wealthy customers. However, there’s a problem. Maeve has a scandalous past, one that her mother, a respectable widow, doesn’t know about. During a recent stint in New York City, Maeve worked as a dancer-for-hire, drank too much bootleg gin, and ended up somewhere she can’t ever mention. Just when she’s getting used to her reinvented self, her past surfaces unexpectedly in the form of Diana Van der Laar.

A socialite whose family fortune comes from South African diamonds, Diana may seem like Maeve’s polar opposite, but they become friends, both women concealing the socially unacceptable parts of their lives out of necessity. But Diana is more complex and damaged than Maeve knows, and the deeper Maeve gets into her world, the more she risks losing sight of her goals.

This gutsy, absorbing story about self-deception and belonging is remarkable in its honesty. The settings exude authenticity, both the scenes of immigrant family life in Boston’s North End and upper-crust society parties, which never go as perfectly as its organizers hope.

The story bounces around time-wise in the beginning, and more details on Maeve’s future plans would have been nice. The wanting more of a novel, though, that’s a good sign. Tessaro is a natural storyteller, and her story goes where it needs to without being predictable. The result is a compelling tale that reads like real life.

Rare Objects was published by Harper in hardcover in April ($25.99, 400pp). The British publisher is Harper UK. This review appeared in May's Historical Novels Review; I had downloaded an e-galley via Edelweiss over the holidays last year, read the first few pages, and got quickly drawn into the story.

Published on May 12, 2016 15:49

May 9, 2016

California’s Golden Age of Winemaking, an essay by Kristen Harnisch

In my review of The California Wife, I mentioned being intrigued by Kristen Harnisch's depiction of the characters' winemaking business; you don't often get to see the inner workings of the wine trade depicted in historical fiction. In today's guest post, she takes us to northern California in the late 19th century, introducing us to the industry pioneers, the techniques they used to make their businesses thrive, and the hardships they endured along the way.

~

California’s Golden Age of Winemaking By Kristen Harnisch, author of The Vintner’s Daughter and The California Wife

Most wine lovers are familiar with the Judgment of Paris, the competition arranged forty years ago by wine expert Steven Spurrier between the best French and California wines. In a blind tasting in 1976, France’s foremost wine experts declared two upstart California wines superior to renowned French bottlings from Bordeaux and Burgundy. This event—so colorfully portrayed in the 2008 movie Bottle Shock—established Napa Valley as one of the world’s greatest winemaking regions. What is not commonly known is that the golden age of winemaking in northern California started during the nineteenth century on the heels of the Gold Rush and was in full swing before the dawn of Prohibition.

Regusci historic Occidental winery (est. 1878)

Regusci historic Occidental winery (est. 1878)

While living in the San Francisco Bay Area and traveling in the Loire Valley of France, I was struck by the beauty of the vineyards and intrigued by how generations of families had battled blight, mildew, rot, and pests to produce fine wines. These vintners approach their work with a centuries-old blend of passion, persistence, art and science. Their dedication sparked the idea for my series about the ambitions of two French-born vintners to establish an American winemaking dynasty at the turn of the twentieth century and set me on a new path of discovery.

The author, biking in NapaResearching vineyard life in the late 1800s was exciting. Visiting a Loire Valley vineyard and touring historic Napa vineyards by bike and on foot were delightful. I snapped photos of ripening grape clusters, scribbled down notes about historic wineries, sifted the rough, porous clay loam through my fingers, and, of course, sampled the wines! I also delved into French and California history books, read years of nineteenth-century trade papers, consulted a master winemaker, and reviewed old maps and photographs at The Napa County Historical Society. Although I had a vague outline for the novels, my research fueled the stories for The Vintner’s Daughter and The California Wife.

The author, biking in NapaResearching vineyard life in the late 1800s was exciting. Visiting a Loire Valley vineyard and touring historic Napa vineyards by bike and on foot were delightful. I snapped photos of ripening grape clusters, scribbled down notes about historic wineries, sifted the rough, porous clay loam through my fingers, and, of course, sampled the wines! I also delved into French and California history books, read years of nineteenth-century trade papers, consulted a master winemaker, and reviewed old maps and photographs at The Napa County Historical Society. Although I had a vague outline for the novels, my research fueled the stories for The Vintner’s Daughter and The California Wife.

The pioneers and economics of the wine trade in the late 1800s provided a treasure-trove of historical drama for the backdrop of the series. Many who came to California for the gold stayed for the rich soil and climate, so perfect for farming sheep, cows, fruit and vegetables. The first northern California winemakers—notables such as Jacob Schram, Charles Krug, Gustave Niebaum, Georges De Latour, Jacob and Frederick Beringer, the Nichelini family and the founders of the Italian-Swiss Colony in Asti—cultivated the first vineyards and the goal that one day their wines would compete with the finest French and European vintages. Chinese laborers, featured in my first novel, formed the backbone of the viticultural industry of California. After they helped build the railways, they found new work picking, pruning and digging cellars out of limestone with their pickaxes.

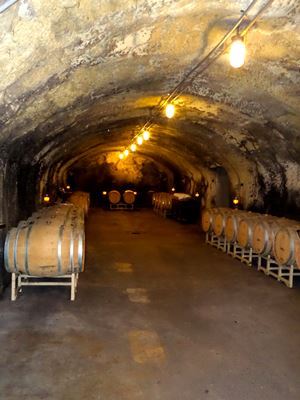

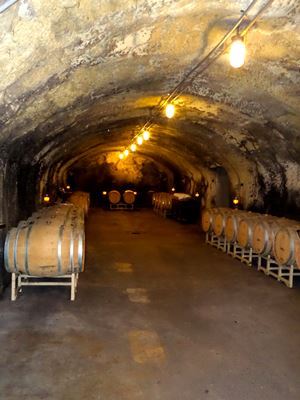

Caves dug by the Chinese in the 1870s

Caves dug by the Chinese in the 1870s

Late in the century, as suspicion and racial hatred toward the Chinese grew, Italian and other European immigrant day laborers replaced them in the fields.

As the century progressed, California women traded their kitchen chores for important roles in family-owned winemaking businesses. In 1886, after her husband’s suicide, Josephine Tyschon finished the Tyschon Winery (now the site of Freemark Abbey) and opened with a capacity of 30,000 gallons. She cultivated 55 acres of zinfandel, reisling and burgundy grapes. Her neighbor, Hannah Weinberger, also took over her family’s winery, with a capacity of 90,000 gallons, after her husband’s death. Weinberger won a silver medal at the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris for her wine, and was the only woman in California to bring home this prestigious award that year. The strength and determination of Sara Thibault, the heroine of my novels, was drawn from these pioneering women.

Edge of Carneros Vines

Edge of Carneros Vines

Just as California wines started to gain global recognition, catastrophe struck. When the phylloxera—a louse that kills grape vines by sucking them dry of nutrients—hit California in the late 1880s, it laid waste to sixty percent of the Napa vineyards. The less hardy gentleman farmers, who’d purchased vineyards for the prestige of making one’s own wines, abandoned their farms and returned to San Francisco. The natives and more savvy newcomers (like my character Philippe Lemieux) took advantage of the cheap land, replanted with phylloxera-resistant rootstock, and grew bumper crops of grapes within five to seven years.

By the late 1890s, after having suffered through the ravages of the phylloxera, California vintners were determined to protect and bolster their wine industry with scientific innovation and creative ways to brand their wines. Most vintners now preferred gravity-flow wineries, invented in the 1870s, to move the grapes through the winemaking process using gravity instead of hoses. In place of head-trained vines, farmers now planted trellis-trained vines, which allowed for the best balance of sun, shading and air circulation through the vines—and yielded far more grapes.

Veraison (the onset of ripening) of pinot noir grapes in June

Veraison (the onset of ripening) of pinot noir grapes in June

As the railway systems improved, vintners shipped their wines to other parts of California and the United States, they opted for the more expensive bottles instead of barrels. Barrels did not offer the advantage of brand identification, and thirsty railway men had been known to drink the wine inside and replace it with water or vinegar. As the supply of wine and eastern demand for it increased, large entities like the California Wine Association refused to pay the grape growers their asking price, and this sparked tensions amid grape growers, who could no longer afford the sky-high labor costs. These price wars drove the price of California wine down, and some of the smaller operations out of business. The largest growers, many who provided sacramental wine to the Catholic Church, also negotiated their own contracts with wine dealers, and found unique ways to thrive during the price wars at the end of the century.

As the railway systems improved, vintners shipped their wines to other parts of California and the United States, they opted for the more expensive bottles instead of barrels. Barrels did not offer the advantage of brand identification, and thirsty railway men had been known to drink the wine inside and replace it with water or vinegar. As the supply of wine and eastern demand for it increased, large entities like the California Wine Association refused to pay the grape growers their asking price, and this sparked tensions amid grape growers, who could no longer afford the sky-high labor costs. These price wars drove the price of California wine down, and some of the smaller operations out of business. The largest growers, many who provided sacramental wine to the Catholic Church, also negotiated their own contracts with wine dealers, and found unique ways to thrive during the price wars at the end of the century.

Intertwining this rich era of winemaking with the story of my characters Sara Thibault and Philippe Lemieux was a true joy. Winemaking, I’ve discovered, is very similar to novel writing: it is an exercise in passion, patience and perseverance! Cheers!

~

The California Wife was published by HarperCollins Canada in February in trade paperback (C$22.99), and the US edition is published by She Writes Press ($17.95) this month. Visit the author's website at www.kristenharnisch.com.

~

California’s Golden Age of Winemaking By Kristen Harnisch, author of The Vintner’s Daughter and The California Wife

Most wine lovers are familiar with the Judgment of Paris, the competition arranged forty years ago by wine expert Steven Spurrier between the best French and California wines. In a blind tasting in 1976, France’s foremost wine experts declared two upstart California wines superior to renowned French bottlings from Bordeaux and Burgundy. This event—so colorfully portrayed in the 2008 movie Bottle Shock—established Napa Valley as one of the world’s greatest winemaking regions. What is not commonly known is that the golden age of winemaking in northern California started during the nineteenth century on the heels of the Gold Rush and was in full swing before the dawn of Prohibition.

Regusci historic Occidental winery (est. 1878)

Regusci historic Occidental winery (est. 1878)While living in the San Francisco Bay Area and traveling in the Loire Valley of France, I was struck by the beauty of the vineyards and intrigued by how generations of families had battled blight, mildew, rot, and pests to produce fine wines. These vintners approach their work with a centuries-old blend of passion, persistence, art and science. Their dedication sparked the idea for my series about the ambitions of two French-born vintners to establish an American winemaking dynasty at the turn of the twentieth century and set me on a new path of discovery.

The author, biking in NapaResearching vineyard life in the late 1800s was exciting. Visiting a Loire Valley vineyard and touring historic Napa vineyards by bike and on foot were delightful. I snapped photos of ripening grape clusters, scribbled down notes about historic wineries, sifted the rough, porous clay loam through my fingers, and, of course, sampled the wines! I also delved into French and California history books, read years of nineteenth-century trade papers, consulted a master winemaker, and reviewed old maps and photographs at The Napa County Historical Society. Although I had a vague outline for the novels, my research fueled the stories for The Vintner’s Daughter and The California Wife.

The author, biking in NapaResearching vineyard life in the late 1800s was exciting. Visiting a Loire Valley vineyard and touring historic Napa vineyards by bike and on foot were delightful. I snapped photos of ripening grape clusters, scribbled down notes about historic wineries, sifted the rough, porous clay loam through my fingers, and, of course, sampled the wines! I also delved into French and California history books, read years of nineteenth-century trade papers, consulted a master winemaker, and reviewed old maps and photographs at The Napa County Historical Society. Although I had a vague outline for the novels, my research fueled the stories for The Vintner’s Daughter and The California Wife. The pioneers and economics of the wine trade in the late 1800s provided a treasure-trove of historical drama for the backdrop of the series. Many who came to California for the gold stayed for the rich soil and climate, so perfect for farming sheep, cows, fruit and vegetables. The first northern California winemakers—notables such as Jacob Schram, Charles Krug, Gustave Niebaum, Georges De Latour, Jacob and Frederick Beringer, the Nichelini family and the founders of the Italian-Swiss Colony in Asti—cultivated the first vineyards and the goal that one day their wines would compete with the finest French and European vintages. Chinese laborers, featured in my first novel, formed the backbone of the viticultural industry of California. After they helped build the railways, they found new work picking, pruning and digging cellars out of limestone with their pickaxes.

Caves dug by the Chinese in the 1870s

Caves dug by the Chinese in the 1870sLate in the century, as suspicion and racial hatred toward the Chinese grew, Italian and other European immigrant day laborers replaced them in the fields.

As the century progressed, California women traded their kitchen chores for important roles in family-owned winemaking businesses. In 1886, after her husband’s suicide, Josephine Tyschon finished the Tyschon Winery (now the site of Freemark Abbey) and opened with a capacity of 30,000 gallons. She cultivated 55 acres of zinfandel, reisling and burgundy grapes. Her neighbor, Hannah Weinberger, also took over her family’s winery, with a capacity of 90,000 gallons, after her husband’s death. Weinberger won a silver medal at the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris for her wine, and was the only woman in California to bring home this prestigious award that year. The strength and determination of Sara Thibault, the heroine of my novels, was drawn from these pioneering women.

Edge of Carneros Vines

Edge of Carneros VinesJust as California wines started to gain global recognition, catastrophe struck. When the phylloxera—a louse that kills grape vines by sucking them dry of nutrients—hit California in the late 1880s, it laid waste to sixty percent of the Napa vineyards. The less hardy gentleman farmers, who’d purchased vineyards for the prestige of making one’s own wines, abandoned their farms and returned to San Francisco. The natives and more savvy newcomers (like my character Philippe Lemieux) took advantage of the cheap land, replanted with phylloxera-resistant rootstock, and grew bumper crops of grapes within five to seven years.

By the late 1890s, after having suffered through the ravages of the phylloxera, California vintners were determined to protect and bolster their wine industry with scientific innovation and creative ways to brand their wines. Most vintners now preferred gravity-flow wineries, invented in the 1870s, to move the grapes through the winemaking process using gravity instead of hoses. In place of head-trained vines, farmers now planted trellis-trained vines, which allowed for the best balance of sun, shading and air circulation through the vines—and yielded far more grapes.

Veraison (the onset of ripening) of pinot noir grapes in June

Veraison (the onset of ripening) of pinot noir grapes in June As the railway systems improved, vintners shipped their wines to other parts of California and the United States, they opted for the more expensive bottles instead of barrels. Barrels did not offer the advantage of brand identification, and thirsty railway men had been known to drink the wine inside and replace it with water or vinegar. As the supply of wine and eastern demand for it increased, large entities like the California Wine Association refused to pay the grape growers their asking price, and this sparked tensions amid grape growers, who could no longer afford the sky-high labor costs. These price wars drove the price of California wine down, and some of the smaller operations out of business. The largest growers, many who provided sacramental wine to the Catholic Church, also negotiated their own contracts with wine dealers, and found unique ways to thrive during the price wars at the end of the century.

As the railway systems improved, vintners shipped their wines to other parts of California and the United States, they opted for the more expensive bottles instead of barrels. Barrels did not offer the advantage of brand identification, and thirsty railway men had been known to drink the wine inside and replace it with water or vinegar. As the supply of wine and eastern demand for it increased, large entities like the California Wine Association refused to pay the grape growers their asking price, and this sparked tensions amid grape growers, who could no longer afford the sky-high labor costs. These price wars drove the price of California wine down, and some of the smaller operations out of business. The largest growers, many who provided sacramental wine to the Catholic Church, also negotiated their own contracts with wine dealers, and found unique ways to thrive during the price wars at the end of the century. Intertwining this rich era of winemaking with the story of my characters Sara Thibault and Philippe Lemieux was a true joy. Winemaking, I’ve discovered, is very similar to novel writing: it is an exercise in passion, patience and perseverance! Cheers!

~

The California Wife was published by HarperCollins Canada in February in trade paperback (C$22.99), and the US edition is published by She Writes Press ($17.95) this month. Visit the author's website at www.kristenharnisch.com.

Published on May 09, 2016 06:12

May 7, 2016

A return to historic Napa: Kristen Harnisch's The California Wife

Second in a series about a Franco-American winemaking family at the turn of the 20th century, The California Wife presents the next stage in life for its heroine and hero – as well as the next step in the development of their winemaking business.

The Vintner’s Daughter

(see earlier review) was an enjoyable romantic saga, and this new entry, which spans 1897 to 1906, is even more involving. Harnisch has hit her stride as a writer: the pacing never flags throughout this lengthy novel, and the many trials that Sara and Philippe Lemieux undergo, separately and together, add new layers to their character.

Sara and Philippe, whose families shared a painful history in France’s Loire Valley, get married and settle on their large California vineyard, planning to raise their orphaned nephew as their own. However, Sara’s desires are torn between making Eagle’s Run a success and her obligations toward her beloved vineyard back home. Competition among local winemakers is heating up; so is pressure from prohibitionists.

Sara and Philippe, whose families shared a painful history in France’s Loire Valley, get married and settle on their large California vineyard, planning to raise their orphaned nephew as their own. However, Sara’s desires are torn between making Eagle’s Run a success and her obligations toward her beloved vineyard back home. Competition among local winemakers is heating up; so is pressure from prohibitionists.

The story brings readers deeply into the economics of the wine industry – a unique historical fiction subject – as the couple negotiates prices, develops creative sales techniques, and secures buyers in Napa and elsewhere. Philippe’s role as primary supplier of sacramental wine to the local archdiocese causes grumblings, and that’s just one impediment to their financial goals.

Although their love remains strong, their married life is equally turbulent. Operating within a male-dominated field, Sara’s vast wine-growing experience is sometimes downplayed, and Philippe’s former mistress introduces a new complication to their happiness.

Later chapters draw in the viewpoint of Sara’s good friend, Marie Chevreau, an experienced midwife who aspires to become a surgeon – another ambitious woman whose presence complements the growing cast. Readers will enjoy being whisked back in time to Napa’s beginnings as a major wine-producing region, and the stage is set for future adventures with these warm-hearted, ambitious characters.

The California Wife was published by HarperCollins Canada in February in trade paperback (C$22.99), and the US edition is published by She Writes Press ($17.95) this month. The review copy was sent to me by the Canadian publisher for review in February's Historical Novels Review.

On Monday, I'll have a guest post from the author about California's historic winemaking industry.

Sara and Philippe, whose families shared a painful history in France’s Loire Valley, get married and settle on their large California vineyard, planning to raise their orphaned nephew as their own. However, Sara’s desires are torn between making Eagle’s Run a success and her obligations toward her beloved vineyard back home. Competition among local winemakers is heating up; so is pressure from prohibitionists.

Sara and Philippe, whose families shared a painful history in France’s Loire Valley, get married and settle on their large California vineyard, planning to raise their orphaned nephew as their own. However, Sara’s desires are torn between making Eagle’s Run a success and her obligations toward her beloved vineyard back home. Competition among local winemakers is heating up; so is pressure from prohibitionists.The story brings readers deeply into the economics of the wine industry – a unique historical fiction subject – as the couple negotiates prices, develops creative sales techniques, and secures buyers in Napa and elsewhere. Philippe’s role as primary supplier of sacramental wine to the local archdiocese causes grumblings, and that’s just one impediment to their financial goals.

Although their love remains strong, their married life is equally turbulent. Operating within a male-dominated field, Sara’s vast wine-growing experience is sometimes downplayed, and Philippe’s former mistress introduces a new complication to their happiness.

Later chapters draw in the viewpoint of Sara’s good friend, Marie Chevreau, an experienced midwife who aspires to become a surgeon – another ambitious woman whose presence complements the growing cast. Readers will enjoy being whisked back in time to Napa’s beginnings as a major wine-producing region, and the stage is set for future adventures with these warm-hearted, ambitious characters.

The California Wife was published by HarperCollins Canada in February in trade paperback (C$22.99), and the US edition is published by She Writes Press ($17.95) this month. The review copy was sent to me by the Canadian publisher for review in February's Historical Novels Review.

On Monday, I'll have a guest post from the author about California's historic winemaking industry.

Published on May 07, 2016 05:00

May 5, 2016

Book review: Chris Cleave's Everyone Brave Is Forgiven, plus giveaway

Loosely based on his grandparents’ WWII-era lives, Cleave’s (Gold, 2012; Little Bee, 2009) intensely felt new novel follows the soul-plumbing journeys of four young Londoners fighting their own personal battles as their world breaks apart.

Loosely based on his grandparents’ WWII-era lives, Cleave’s (Gold, 2012; Little Bee, 2009) intensely felt new novel follows the soul-plumbing journeys of four young Londoners fighting their own personal battles as their world breaks apart.They include aristocratic Mary North, who derives unexpected purpose from teaching city children after their more socially acceptable peers are evacuated to the countryside; her friend Hilda; Tom, Mary’s middle-class supervisor and lover; and his roommate, Alistair, a Royal Artillery officer.

Mary and Alistair’s mutual attraction complicates matters yet serves as a lifeline for them both. Just as transformative for Mary are her mentorship of an African American student, which almost everyone disapproves of, and her up-and-down relationship with Hilda, one shaped by their joint experiences and occasional jealousy.

Full of insight and memorably original phrasings, the story is leavened by sardonic humor, although the consistently high level of wit in the dialogue sometimes feels unrealistic. Cleave paints an emotion-filled portrait of a damaged city with its inequities amplified by war and of courageous individuals whose connections to one another make them stronger.

Everyone Brave Is Forgiven was published by Simon & Schuster in hardcover this week ($26, 432pp). This review first appeared in Booklist's March 1st issue, and I covered it from an ARC provided by my editor.

Since then, the publisher has sent me a nice new hardcover copy, so I have an extra that I thought I'd give away to another blog reader. Just fill out the form below if you're interested. One entry per household, please; void where prohibited. Deadline for entry Friday, March 13th. I'll announce the winner here (and notify them) shortly thereafter. Good luck!

Loading...

Published on May 05, 2016 05:00

May 3, 2016

Reading historical fiction in search of meaning, a guest post by Linda Kass, author of Tasa's Song

Author Linda Kass has contributed an essay about her methods and intent in writing historical fiction, and what readers can gain from reading in the genre. Her debut novel Tasa's Song is published today by She Writes Press.

~

Reading Historical Fiction in Search of Meaning

Linda Kass

In historical fiction, the details of an era, and the particularities of settings during that time period, must ring true. All the more necessary when the context is universally known, such as a major historic event. Certain facts need to ground historical and realistic fiction, but those facts cannot overpower the story itself.

In historical fiction, the details of an era, and the particularities of settings during that time period, must ring true. All the more necessary when the context is universally known, such as a major historic event. Certain facts need to ground historical and realistic fiction, but those facts cannot overpower the story itself.

My novel, Tasa’s Song, is based on the true events of my mother’s early life in eastern Poland during the gathering storm of World War II, a backdrop that has been called the most significant war the human race has ever waged. My protagonist, Tasa Rosinski, is a violin prodigy. She has an extended family. Life amid war produces movement for all of the characters from one place to another. My challenge was to portray Tasa, a fictional and unique character, in a specific historic context and setting while she faces known circumstances.

As a journalist, I am attached to facts, but as a novelist, I can only use them to create a verisimilitude on the page. For Tasa’s Song, I researched facts in order to write authentic scenes and dialogue and action. What did Tasa’s small village in Podkamien look like? What foods did she and her family eat? What clothing did they wear? How did people get around then? What did Polish farmers grow on their land? How did people learn about what was going on at that time? What did they listen to on the radio? What books did they read? What musical compositions might Tasa have played as her talent developed? What historical events would be topical to Tasa’s family in 1935, 1941, or 1944?

author Linda Kass

author Linda Kass

(credit: Lorn Spolter Photography)

As a writer of historical fiction, I needed to understand the concrete world in which my characters lived and interacted. But the writer’s task when creating a story set in a particular time and place is not to be true to the facts as recorded in source material. That’s the role of the historian. The historical novelist exposes the reader to the inner lives of people across time and place, and in doing so illuminates history’s untold stories, allowing the reader to experience a more complex truth.

The essence of any fictional story is its characters. They are vivid because, while participating in the flow of historic events, they make their own choices, have their own thoughts, experience joy or suffering in their own way. For Tasa, she endures through the solace of music, the love for her family, and the memories she holds inside. The fact of history tells us that many people suffered during World War II. The character of Tasa reveals her unique emotional suffering.

Reading history allows us to understand what happened. Reading historical fiction allows us to be moved by what happened. Yet, even after we know the facts, we continue to search for sense and meaning. That is at the essence of our humanity.

~

Linda Kass is a writer who worked as a magazine reporter and correspondent for regional and national publications early in her career. In her community, Ms. Kass is a strong advocate of education, literacy, and the arts, and is a long distance road cyclist who rides in an annual event to support cancer research. Her past experience as a trustee and board chair of the Columbus Symphony Orchestra fed into much of the music that fills the pages of Tasa's Song (She Writes Press, trade pb/$16.95). She is at work on a second novel. You can learn more at http://www.lindakass.com/.

~

Reading Historical Fiction in Search of Meaning

Linda Kass

In historical fiction, the details of an era, and the particularities of settings during that time period, must ring true. All the more necessary when the context is universally known, such as a major historic event. Certain facts need to ground historical and realistic fiction, but those facts cannot overpower the story itself.

In historical fiction, the details of an era, and the particularities of settings during that time period, must ring true. All the more necessary when the context is universally known, such as a major historic event. Certain facts need to ground historical and realistic fiction, but those facts cannot overpower the story itself.My novel, Tasa’s Song, is based on the true events of my mother’s early life in eastern Poland during the gathering storm of World War II, a backdrop that has been called the most significant war the human race has ever waged. My protagonist, Tasa Rosinski, is a violin prodigy. She has an extended family. Life amid war produces movement for all of the characters from one place to another. My challenge was to portray Tasa, a fictional and unique character, in a specific historic context and setting while she faces known circumstances.

As a journalist, I am attached to facts, but as a novelist, I can only use them to create a verisimilitude on the page. For Tasa’s Song, I researched facts in order to write authentic scenes and dialogue and action. What did Tasa’s small village in Podkamien look like? What foods did she and her family eat? What clothing did they wear? How did people get around then? What did Polish farmers grow on their land? How did people learn about what was going on at that time? What did they listen to on the radio? What books did they read? What musical compositions might Tasa have played as her talent developed? What historical events would be topical to Tasa’s family in 1935, 1941, or 1944?

author Linda Kass

author Linda Kass(credit: Lorn Spolter Photography)

As a writer of historical fiction, I needed to understand the concrete world in which my characters lived and interacted. But the writer’s task when creating a story set in a particular time and place is not to be true to the facts as recorded in source material. That’s the role of the historian. The historical novelist exposes the reader to the inner lives of people across time and place, and in doing so illuminates history’s untold stories, allowing the reader to experience a more complex truth.

The essence of any fictional story is its characters. They are vivid because, while participating in the flow of historic events, they make their own choices, have their own thoughts, experience joy or suffering in their own way. For Tasa, she endures through the solace of music, the love for her family, and the memories she holds inside. The fact of history tells us that many people suffered during World War II. The character of Tasa reveals her unique emotional suffering.

Reading history allows us to understand what happened. Reading historical fiction allows us to be moved by what happened. Yet, even after we know the facts, we continue to search for sense and meaning. That is at the essence of our humanity.

~

Linda Kass is a writer who worked as a magazine reporter and correspondent for regional and national publications early in her career. In her community, Ms. Kass is a strong advocate of education, literacy, and the arts, and is a long distance road cyclist who rides in an annual event to support cancer research. Her past experience as a trustee and board chair of the Columbus Symphony Orchestra fed into much of the music that fills the pages of Tasa's Song (She Writes Press, trade pb/$16.95). She is at work on a second novel. You can learn more at http://www.lindakass.com/.

Published on May 03, 2016 04:00

April 30, 2016

A guide to the historical novels at BEA 2016

Here’s my 7th annual guide to the historical novels at BEA. This is a work in progress, pieced together from BEA’s autographing schedules, Publishers Weekly’s adult “galleys to grab” guide, posted schedules from publishers, Twitter, etc. I've added booth numbers, book descriptions, release dates, etc. It will be updated periodically up until I leave for Chicago on May 10th, so if you plan to print it out, I suggest waiting until just before the show; Library Journal's forthcoming galley guide (out around 5/9) should list other relevant titles.

Additions and corrections are welcome. Leave a comment below or tweet me @readingthepast.

~Galleys to Grab~

Algonquin (Workman) - booth 1829

Caroline Leavitt, Cruel Beautiful World - novel of sisterhood, family, and responsibility in the late 1960s. Oct.

Caroline Leavitt, Cruel Beautiful World - novel of sisterhood, family, and responsibility in the late 1960s. Oct.

Susan Rivers, The Second Mrs. Hockaday - love, the desperation of wartime, and a mysterious crime, set during the Civil War. Jan 2017.

Bloomsbury - booth 1859

John Pipkin, The Blind Astronomer’s Daughter - love and scientific discovery in late 18th-century Ireland. Oct.

John Pipkin, The Blind Astronomer’s Daughter - love and scientific discovery in late 18th-century Ireland. Oct.

Kate Saunders, The Secrets of Wishtide - crime novel featuring a widow in 19th-century Lincolnshire. Sept.

Europa - booth 1945

Joan London, The Golden Age - a convalescent hospital in Perth, Australia, is the scene for healing, love, and dislocation in the postwar era, from a well-known Australian novelist. Aug.

Hachette - booths 1716, 1717

Emma Donoghue, The Wonder - a mysterious child who claims to live without sustenance in 1850s rural Ireland may be a fraud. Little Brown, Sept.

Robert Hicks, The Orphan Mother - the story of Mariah Reddick, former slave of the heroine from The Widow of the South. Grand Central, Sept.

HarperCollins - booths 2140, 2141

HarperCollins - booths 2140, 2141

Jessie Burton, The Muse - the Spanish Civil War and 1960s London intertwine in a tale of art and mystery. Ecco, July.

Helen Sedgwick, The Comet Seekers - the past, present, and future of two lovers in modern Antarctica; literary, centuries-spanning epic. Harper, Oct.

Macmillan - booth 1958 (see full schedule)

Ronald Balson, Karolina’s Twins - giveaway 5/13, 11:30am - a modern search for two Polish sisters lost during WWII; multi-period. St. Martin's, Sept.

Andrew Gross, The One Man - giveaway 5/13, 11:30am - historical thriller set during the Holocaust.

Andrew Gross, The One Man - giveaway 5/13, 11:30am - historical thriller set during the Holocaust.

Lian Hearn, Emperor of the Eight Islands - giveaway 5/11, 3:30pm. First in her new Japanese historical fantasy quartet. FSG, April.

Rae Meadows, I Will Send Rain - giveaway 5/11, 4:30pm - a woman fights to save her family in Dust Bowl Oklahoma. Henry Holt, Aug.

Steven Price, By Gaslight - giveaway 5/12, 2:30pm - American detective William Pinkerton investigates a murder in 1885 London. FSG, Oct.

Penguin Random House - booths 2433, 2441

Penguin Random House - booths 2433, 2441

Jennifer Chiaverini, Fates and Traitors - a novel of John Wilkes Booth, as seen from four women’s perspectives. Dutton, Sept.

Amor Towles, A Gentleman in Moscow - in 1922, a Russian aristocrat endures house arrest in a hotel across from the Kremlin. Viking, Sept. See also under signings.

Sourcebooks - booth 2333 (see full schedule)

Marie Benedict, The Other Einstein - the little-known story of Mileva Maric Einstein, a physicist in her own right. Oct. Giveaway Fri 5/13, 9am.

Cuyler Overholt, A Deadly Affection - historical mystery set in early 20th-c NYC. Sept. Giveaway Wed 5/11, 1pm.

Greer MacAllister, Girl in Disguise - Kate Warne, the first female Pinkerton detective, and her adventurous life during the Civil War years. Mar. 2017. Giveaway Fri 5/13, 1pm.

~Author Signings~

Thu May 12

Thu May 12

10 - 10:30am, booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)

Graham Moore, The Last Days of Night - historical thriller about the battle between Edison and Westinghouse to electrify America, from the author of The Sherlockian. RH, Sept.

10:00-10:30, Table 1

Jennifer Chiaverini, Fates and Traitors - see above under Galleys. Dutton, Sept.

10 - 10:30am, Table 6

Affinity Konar, Mischling - twin sisters endure Auschwitz, Mengele’s experiments, and the aftermath of war. Little Brown/Lee Boudreaux, Sept.

11:30am, Booth 2333 (Sourcebooks)

11:30am, Booth 2333 (Sourcebooks)

Marie Benedict, The Other Einstein - see above under Galleys.

2-2:45pm, Booth 1204-1205 (Grove Atlantic)

Andrea Molesini, Not All Bastards Are From Vienna - a family in a northern Italian village has their villa requisitioned by enemy troops during WWI. Grove, Feb.

2-2:30pm, Booth 2366 (Counterpoint)

Kim Brooks, The Houseguest - in 1940s America, a Russian immigrant takes in a glamorous refugee. Apr.

3:30-4pm, Booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)

3:30-4pm, Booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)

Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad - one woman’s quest to escape the bonds of slavery in 19th-century America. Doubleday, Sept.

4-4:30pm, Booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)

Amor Towles, A Gentleman in Moscow - see above under Galleys.

Fri May 13th

10-11am, Table 4

Robert Hicks, The Orphan Mother - see above under Galleys.

10:30-11:30am, Booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)

Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing - a literary epic spanning centuries in Ghana and America. Knopf, May.

Signings TBA (in the PW galley guide, but no date/time listed):

Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster

Chris Cleave, Everyone Brave is Forgiven - ordinary people trying to survive the London Blitz and its aftermath. S&S, Apr.

Thomas Mullen, Darktown - a police procedural set in postwar Atlanta as two black policemen pursue justice for a murdered woman. Atria, Sept.

WW Norton

Winston Groom, El Paso - historical epic centering on the Mexican Revolution of the early 20th century. Liveright, Oct.

Additions and corrections are welcome. Leave a comment below or tweet me @readingthepast.

~Galleys to Grab~

Algonquin (Workman) - booth 1829

Caroline Leavitt, Cruel Beautiful World - novel of sisterhood, family, and responsibility in the late 1960s. Oct.

Caroline Leavitt, Cruel Beautiful World - novel of sisterhood, family, and responsibility in the late 1960s. Oct.Susan Rivers, The Second Mrs. Hockaday - love, the desperation of wartime, and a mysterious crime, set during the Civil War. Jan 2017.

Bloomsbury - booth 1859

John Pipkin, The Blind Astronomer’s Daughter - love and scientific discovery in late 18th-century Ireland. Oct.

John Pipkin, The Blind Astronomer’s Daughter - love and scientific discovery in late 18th-century Ireland. Oct.Kate Saunders, The Secrets of Wishtide - crime novel featuring a widow in 19th-century Lincolnshire. Sept.

Europa - booth 1945

Joan London, The Golden Age - a convalescent hospital in Perth, Australia, is the scene for healing, love, and dislocation in the postwar era, from a well-known Australian novelist. Aug.

Hachette - booths 1716, 1717

Emma Donoghue, The Wonder - a mysterious child who claims to live without sustenance in 1850s rural Ireland may be a fraud. Little Brown, Sept.

Robert Hicks, The Orphan Mother - the story of Mariah Reddick, former slave of the heroine from The Widow of the South. Grand Central, Sept.

HarperCollins - booths 2140, 2141

HarperCollins - booths 2140, 2141 Jessie Burton, The Muse - the Spanish Civil War and 1960s London intertwine in a tale of art and mystery. Ecco, July.

Helen Sedgwick, The Comet Seekers - the past, present, and future of two lovers in modern Antarctica; literary, centuries-spanning epic. Harper, Oct.

Macmillan - booth 1958 (see full schedule)

Ronald Balson, Karolina’s Twins - giveaway 5/13, 11:30am - a modern search for two Polish sisters lost during WWII; multi-period. St. Martin's, Sept.

Andrew Gross, The One Man - giveaway 5/13, 11:30am - historical thriller set during the Holocaust.

Andrew Gross, The One Man - giveaway 5/13, 11:30am - historical thriller set during the Holocaust.Lian Hearn, Emperor of the Eight Islands - giveaway 5/11, 3:30pm. First in her new Japanese historical fantasy quartet. FSG, April.

Rae Meadows, I Will Send Rain - giveaway 5/11, 4:30pm - a woman fights to save her family in Dust Bowl Oklahoma. Henry Holt, Aug.

Steven Price, By Gaslight - giveaway 5/12, 2:30pm - American detective William Pinkerton investigates a murder in 1885 London. FSG, Oct.

Penguin Random House - booths 2433, 2441

Penguin Random House - booths 2433, 2441 Jennifer Chiaverini, Fates and Traitors - a novel of John Wilkes Booth, as seen from four women’s perspectives. Dutton, Sept.

Amor Towles, A Gentleman in Moscow - in 1922, a Russian aristocrat endures house arrest in a hotel across from the Kremlin. Viking, Sept. See also under signings.

Sourcebooks - booth 2333 (see full schedule)

Marie Benedict, The Other Einstein - the little-known story of Mileva Maric Einstein, a physicist in her own right. Oct. Giveaway Fri 5/13, 9am.

Cuyler Overholt, A Deadly Affection - historical mystery set in early 20th-c NYC. Sept. Giveaway Wed 5/11, 1pm.

Greer MacAllister, Girl in Disguise - Kate Warne, the first female Pinkerton detective, and her adventurous life during the Civil War years. Mar. 2017. Giveaway Fri 5/13, 1pm.

~Author Signings~

Thu May 12

Thu May 12 10 - 10:30am, booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)

Graham Moore, The Last Days of Night - historical thriller about the battle between Edison and Westinghouse to electrify America, from the author of The Sherlockian. RH, Sept.

10:00-10:30, Table 1

Jennifer Chiaverini, Fates and Traitors - see above under Galleys. Dutton, Sept.

10 - 10:30am, Table 6

Affinity Konar, Mischling - twin sisters endure Auschwitz, Mengele’s experiments, and the aftermath of war. Little Brown/Lee Boudreaux, Sept.

11:30am, Booth 2333 (Sourcebooks)

11:30am, Booth 2333 (Sourcebooks)Marie Benedict, The Other Einstein - see above under Galleys.

2-2:45pm, Booth 1204-1205 (Grove Atlantic)

Andrea Molesini, Not All Bastards Are From Vienna - a family in a northern Italian village has their villa requisitioned by enemy troops during WWI. Grove, Feb.

2-2:30pm, Booth 2366 (Counterpoint)

Kim Brooks, The Houseguest - in 1940s America, a Russian immigrant takes in a glamorous refugee. Apr.

3:30-4pm, Booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)

3:30-4pm, Booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad - one woman’s quest to escape the bonds of slavery in 19th-century America. Doubleday, Sept.

4-4:30pm, Booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)

Amor Towles, A Gentleman in Moscow - see above under Galleys.

Fri May 13th

10-11am, Table 4

Robert Hicks, The Orphan Mother - see above under Galleys.

10:30-11:30am, Booth 2433 (Penguin Random House)

Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing - a literary epic spanning centuries in Ghana and America. Knopf, May.

Signings TBA (in the PW galley guide, but no date/time listed):

Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster Chris Cleave, Everyone Brave is Forgiven - ordinary people trying to survive the London Blitz and its aftermath. S&S, Apr.

Thomas Mullen, Darktown - a police procedural set in postwar Atlanta as two black policemen pursue justice for a murdered woman. Atria, Sept.

WW Norton

Winston Groom, El Paso - historical epic centering on the Mexican Revolution of the early 20th century. Liveright, Oct.

Published on April 30, 2016 08:06

April 27, 2016

On Romney Marsh: a guest post by AJ MacKenzie, author of The Body on the Doorstep

The authors who write as A.J. MacKenzie are stopping by with an essay (accompanied by some gorgeous photos) about the beautiful and atmospheric Romney Marsh. This landscape figures in their new novel The Body on the Doorstep (Zaffre, hb and ebook), first in the appropriately-titled Romney Marsh Mysteries set in the south-east of England in the 1790s.

~

On Romney Marsh

A.J. MacKenzie

‘The Fifth Continent’ is how a nineteenth-century clergyman once described Romney Marsh, and even today that sense of separateness and isolation is still there. A major road now crosses the Marsh, and you can drive across it from Rye to Hythe in just a few minutes. But the Marsh is still a distinct place. The hills of the Weald of Kent close off one side of the triangle of the Marsh, marking the beginnings of a distinctly different landscape; on the other two sides is the sea, sweeping up onto beaches of sand and shingle.

‘The Fifth Continent’ is how a nineteenth-century clergyman once described Romney Marsh, and even today that sense of separateness and isolation is still there. A major road now crosses the Marsh, and you can drive across it from Rye to Hythe in just a few minutes. But the Marsh is still a distinct place. The hills of the Weald of Kent close off one side of the triangle of the Marsh, marking the beginnings of a distinctly different landscape; on the other two sides is the sea, sweeping up onto beaches of sand and shingle.

Get off that main road, and Romney Marsh is quiet. Inland, the villages are small and peaceful. Many are little larger than they were in the Middle Ages; some are actually smaller, and some of the old settlements have disappeared entirely. Hope was once a thriving village not far from New Romney; now, only the crumbling remnants of its church still stand. St Mary in the Marsh, the central location of The Body on the Doorstep, is mostly new buildings; only the church and the Star Inn still survive from earlier days.

St. Mary in the Marsh churchyard, looking west to Hills at Appledore

St. Mary in the Marsh churchyard, looking west to Hills at Appledore

There is of course much new building on the Marsh. You only need to turn your eyes south, to the great blocky shape of Dungeness power station and the white towers of the wind farm on Walland Marsh, to see this. But it is also quite easy strip away the accretions of time. Maps help; we found several late eighteenth century maps of Romney Marsh, and with these it is easy to see how the coastline has changed and settlement patterns have shifted.

St. Mary in the Marsh tower

St. Mary in the Marsh tower

And apart from that main arterial road, the Marsh is also quiet. The roads are empty. It is possible, if you want to drive at the speed of a trotting carriage to see how long it will take to ride from Appledore to St Mary, to do so, and no one will bother you. You can abandon your car and walk the tracks and footpaths where Hardcastle and Mrs Chaytor walked, and the loudest sound you will hear is the twittering of birds or in spring, the baa-ing of lambs. Behind the roads and houses and power stations, the Marsh’s past is there, plain to see.

Romney Marsh, with Hills of Lympne in the distance

Romney Marsh, with Hills of Lympne in the distance

The weather impacts on Romney Marsh like few other places in England. The flat land offers no breaks from the wind; storms from the Channel roar over the Marsh with nothing to stop them. In the heat, there are few trees to offer shade from the sun. When it rains there, it really rains. The weather is dramatic, and it sets the mood. It will be no surprise to anyone who know Romney Marsh that weather plays a big part in The Body on the Doorstep.

St. Mary in the Marsh, taken from the West

St. Mary in the Marsh, taken from the West

Most of all, the Marsh is beautiful. We don’t know whether JMW Turner ever painted there or not, but it would not surprise us; it is the sort of austere space of land and sky and sea that he loved. In The Body on the Doorstep, Turner went to Romney Marsh seeking inspiration; Hardcastle went seeking peace; Amelia Chaytor went to find solitude. We went, and found a story.

~

A.J. MacKenzie is the pseudonym of Marilyn Livingstone and Morgen Witzel, a collaborative Anglo-Canadian husband-and-wife duo.

A.J. MacKenzie is the pseudonym of Marilyn Livingstone and Morgen Witzel, a collaborative Anglo-Canadian husband-and-wife duo.

Between them they have written more than twenty non-fiction and academic titles, with specialisms including management, medieval economic history and medieval warfare. See their website at http://www.ajmackenzienovels.com.

This essay forms part of the authors' blog tour; see the other stops as listed below. (photo credit: Vicky Stottor/Shuv Williams)

~

~

On Romney Marsh

A.J. MacKenzie

‘The Fifth Continent’ is how a nineteenth-century clergyman once described Romney Marsh, and even today that sense of separateness and isolation is still there. A major road now crosses the Marsh, and you can drive across it from Rye to Hythe in just a few minutes. But the Marsh is still a distinct place. The hills of the Weald of Kent close off one side of the triangle of the Marsh, marking the beginnings of a distinctly different landscape; on the other two sides is the sea, sweeping up onto beaches of sand and shingle.

‘The Fifth Continent’ is how a nineteenth-century clergyman once described Romney Marsh, and even today that sense of separateness and isolation is still there. A major road now crosses the Marsh, and you can drive across it from Rye to Hythe in just a few minutes. But the Marsh is still a distinct place. The hills of the Weald of Kent close off one side of the triangle of the Marsh, marking the beginnings of a distinctly different landscape; on the other two sides is the sea, sweeping up onto beaches of sand and shingle. Get off that main road, and Romney Marsh is quiet. Inland, the villages are small and peaceful. Many are little larger than they were in the Middle Ages; some are actually smaller, and some of the old settlements have disappeared entirely. Hope was once a thriving village not far from New Romney; now, only the crumbling remnants of its church still stand. St Mary in the Marsh, the central location of The Body on the Doorstep, is mostly new buildings; only the church and the Star Inn still survive from earlier days.

St. Mary in the Marsh churchyard, looking west to Hills at Appledore

St. Mary in the Marsh churchyard, looking west to Hills at AppledoreThere is of course much new building on the Marsh. You only need to turn your eyes south, to the great blocky shape of Dungeness power station and the white towers of the wind farm on Walland Marsh, to see this. But it is also quite easy strip away the accretions of time. Maps help; we found several late eighteenth century maps of Romney Marsh, and with these it is easy to see how the coastline has changed and settlement patterns have shifted.

St. Mary in the Marsh tower

St. Mary in the Marsh towerAnd apart from that main arterial road, the Marsh is also quiet. The roads are empty. It is possible, if you want to drive at the speed of a trotting carriage to see how long it will take to ride from Appledore to St Mary, to do so, and no one will bother you. You can abandon your car and walk the tracks and footpaths where Hardcastle and Mrs Chaytor walked, and the loudest sound you will hear is the twittering of birds or in spring, the baa-ing of lambs. Behind the roads and houses and power stations, the Marsh’s past is there, plain to see.

Romney Marsh, with Hills of Lympne in the distance

Romney Marsh, with Hills of Lympne in the distanceThe weather impacts on Romney Marsh like few other places in England. The flat land offers no breaks from the wind; storms from the Channel roar over the Marsh with nothing to stop them. In the heat, there are few trees to offer shade from the sun. When it rains there, it really rains. The weather is dramatic, and it sets the mood. It will be no surprise to anyone who know Romney Marsh that weather plays a big part in The Body on the Doorstep.

St. Mary in the Marsh, taken from the West

St. Mary in the Marsh, taken from the WestMost of all, the Marsh is beautiful. We don’t know whether JMW Turner ever painted there or not, but it would not surprise us; it is the sort of austere space of land and sky and sea that he loved. In The Body on the Doorstep, Turner went to Romney Marsh seeking inspiration; Hardcastle went seeking peace; Amelia Chaytor went to find solitude. We went, and found a story.

~

A.J. MacKenzie is the pseudonym of Marilyn Livingstone and Morgen Witzel, a collaborative Anglo-Canadian husband-and-wife duo.

A.J. MacKenzie is the pseudonym of Marilyn Livingstone and Morgen Witzel, a collaborative Anglo-Canadian husband-and-wife duo.Between them they have written more than twenty non-fiction and academic titles, with specialisms including management, medieval economic history and medieval warfare. See their website at http://www.ajmackenzienovels.com.

This essay forms part of the authors' blog tour; see the other stops as listed below. (photo credit: Vicky Stottor/Shuv Williams)

~

Published on April 27, 2016 22:00