Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 74

January 14, 2017

The Chosen Maiden by Eva Stachniak, an expressive novel about Polish dancer and choreographer Bronislava Nijinska

One can rely on Stachniak (The Winter Palace, 2012) for engaging, well-researched fictional portraits of dynamic historical women. As her story of renowned Polish ballerina and choreographer Bronislava Nijinska unfolds against the politically troubled backdrop of late nineteenth- through mid-twentieth-century Europe, readers become both active participants in her continual pursuit of creative excellence in dance and captivated spectators.

One can rely on Stachniak (The Winter Palace, 2012) for engaging, well-researched fictional portraits of dynamic historical women. As her story of renowned Polish ballerina and choreographer Bronislava Nijinska unfolds against the politically troubled backdrop of late nineteenth- through mid-twentieth-century Europe, readers become both active participants in her continual pursuit of creative excellence in dance and captivated spectators.Born in Minsk to traveling professional dancers, Bronia’s early life and rigorous training at Saint Petersburg’s Imperial Ballet School are dominated by her older brother, Vaslav Nijinsky, depicted as an artistic genius whose daring performances motivate her—and overshadow her own talents. Around this time, ballet is moving from its formal, classical roots into more fluid forms of expression, and Vaslav and Bronia are part of this controversial transformation.

As she emerges as an innovative artist in her own right, Bronia’s working relationship with impresario Serge Diaghilev—founder of the Ballets Russes, her brother’s probable lover, and for whose company she dances and choreographs in Paris and elsewhere—is portrayed with skill. With striking depth of feeling, Stachniak brings us firsthand into the moments when Bronia embodies the onstage personas she creates.

The novel also illustrates her family life, including marital discord, Vaslav’s increasing mental instability, and the value of motherhood. A memorable literary rendering of a remarkable woman’s life.

The Chosen Maiden will be published by Doubleday Canada next Tuesday (464pp, trade pb, $18 US, or $24 in Canada). This review was submitted for publication in Booklist's January 1st issue. While the publisher is Canadian, the book is being distributed in the US, so American readers shouldn't have trouble obtaining it.

Published on January 14, 2017 08:19

January 10, 2017

Nicola Cornick's The Phantom Tree, a time-slip mystery of modern and Tudor England

It's easy to feel sorry for Mary Seymour. Daughter of Henry VIII’s widow, Katherine Parr, and her reckless fourth husband, who was executed for treason, Mary was orphaned by her first birthday. A burden to her relatives during her life, she was also obscure in death, which has gone unrecorded. Many assume she died as a child, but the speculation that she survived to adulthood presents a provocative “what if.”

Nicola Cornick’s second romantic time-slip novel (after

House of Shadows

) is a historically rich work that uses this premise as the springboard for a story about an unlikely sisterhood that extends into two eras.

Nicola Cornick’s second romantic time-slip novel (after

House of Shadows

) is a historically rich work that uses this premise as the springboard for a story about an unlikely sisterhood that extends into two eras.

Alison Bannister, née Banastre, was born into the 16th century but has somehow been trapped in the 21st century for over a decade. She and Mary Seymour had spent their later childhood and adolescence together at Wolf Hall in Wiltshire, along with a passel of other orphaned cousins. Several years separate the pair, and their personalities are too different to allow for friendship: Alison is beautiful yet hard-edged, while Mary is innocent and naïve, and Mary’s higher social standing invites feelings of jealousy. Still, later circumstances compel them into a pact. Alison had helped Mary flee a dangerous situation at Wolf Hall, and in exchange, she demands Mary’s assistance in finding the son she was forced to give up.

Unable to return to her own time, Alison has made a new life for herself in modern England but doesn’t let herself get close to anyone; she remains haunted by her lost child. Her first clues on what happened to him emerge via a portrait of Mary, which she finds while browsing an antique shop in Marlborough. Unfortunately for Alison, examining the painting’s provenance and the objects depicted within it means reconnecting with an old flame, Adam Hewer, a rising celebrity historian who’s staked his career on its identification as a newly discovered Anne Boleyn portrait.

Adam shows dubious professional judgment, as do the portrait’s modern authenticators, but he’s willing to concede he may be wrong. Several mysteries are carefully woven through both timelines. What became of Alison’s son? What forced Mary to leave Wolf Hall? What’s the true identity of the mysterious man who communicates telepathically with Mary? Perhaps written as a touching homage to Mary Stewart’s classic Touch Not the Cat, Mary’s secret relationship with this man she’s never seen is often her sole source of hope.

author Nicola CornickCornick’s portrait of country life in Tudor England is presented with a tactile clarity that avoids romanticizing the time. One can feel the damp chill that pervades Wolf Hall in winter, smell the ripe odors of the local market, and observe how women’s powerlessness gives rise to discord and rancor. Alison’s under no illusion about a woman’s lot back then – if not for her missing son, she’d stay put in 2016 – and a wonderful scene of her present-day visit to a medieval church illustrates this. Moreover, Alison’s attempts to locate the past via modern clues demonstrate how much the past remains with us.

author Nicola CornickCornick’s portrait of country life in Tudor England is presented with a tactile clarity that avoids romanticizing the time. One can feel the damp chill that pervades Wolf Hall in winter, smell the ripe odors of the local market, and observe how women’s powerlessness gives rise to discord and rancor. Alison’s under no illusion about a woman’s lot back then – if not for her missing son, she’d stay put in 2016 – and a wonderful scene of her present-day visit to a medieval church illustrates this. Moreover, Alison’s attempts to locate the past via modern clues demonstrate how much the past remains with us.

There were traces of history everywhere: in street names, on inn signs, in old tracks and ancient hedgerows, buried walls and tumbled gravestones. Scratch the surface and it was there.

The Phantom Tree is a skillfully written multi-stranded mystery with thoughtful reflections on two women’s quests for belonging. Read it not only for its evocation of the 16th century but for greater appreciation of the conveniences and freedoms we take for granted today.

The Phantom Tree was published by HarperCollins UK's HQ imprint on 29 December (£7.99, paperback). Thanks to the publisher for approving my NetGalley access; this is the second stop on the book's blog tour.

Nicola Cornick’s second romantic time-slip novel (after

House of Shadows

) is a historically rich work that uses this premise as the springboard for a story about an unlikely sisterhood that extends into two eras.

Nicola Cornick’s second romantic time-slip novel (after

House of Shadows

) is a historically rich work that uses this premise as the springboard for a story about an unlikely sisterhood that extends into two eras. Alison Bannister, née Banastre, was born into the 16th century but has somehow been trapped in the 21st century for over a decade. She and Mary Seymour had spent their later childhood and adolescence together at Wolf Hall in Wiltshire, along with a passel of other orphaned cousins. Several years separate the pair, and their personalities are too different to allow for friendship: Alison is beautiful yet hard-edged, while Mary is innocent and naïve, and Mary’s higher social standing invites feelings of jealousy. Still, later circumstances compel them into a pact. Alison had helped Mary flee a dangerous situation at Wolf Hall, and in exchange, she demands Mary’s assistance in finding the son she was forced to give up.

Unable to return to her own time, Alison has made a new life for herself in modern England but doesn’t let herself get close to anyone; she remains haunted by her lost child. Her first clues on what happened to him emerge via a portrait of Mary, which she finds while browsing an antique shop in Marlborough. Unfortunately for Alison, examining the painting’s provenance and the objects depicted within it means reconnecting with an old flame, Adam Hewer, a rising celebrity historian who’s staked his career on its identification as a newly discovered Anne Boleyn portrait.

Adam shows dubious professional judgment, as do the portrait’s modern authenticators, but he’s willing to concede he may be wrong. Several mysteries are carefully woven through both timelines. What became of Alison’s son? What forced Mary to leave Wolf Hall? What’s the true identity of the mysterious man who communicates telepathically with Mary? Perhaps written as a touching homage to Mary Stewart’s classic Touch Not the Cat, Mary’s secret relationship with this man she’s never seen is often her sole source of hope.

author Nicola CornickCornick’s portrait of country life in Tudor England is presented with a tactile clarity that avoids romanticizing the time. One can feel the damp chill that pervades Wolf Hall in winter, smell the ripe odors of the local market, and observe how women’s powerlessness gives rise to discord and rancor. Alison’s under no illusion about a woman’s lot back then – if not for her missing son, she’d stay put in 2016 – and a wonderful scene of her present-day visit to a medieval church illustrates this. Moreover, Alison’s attempts to locate the past via modern clues demonstrate how much the past remains with us.

author Nicola CornickCornick’s portrait of country life in Tudor England is presented with a tactile clarity that avoids romanticizing the time. One can feel the damp chill that pervades Wolf Hall in winter, smell the ripe odors of the local market, and observe how women’s powerlessness gives rise to discord and rancor. Alison’s under no illusion about a woman’s lot back then – if not for her missing son, she’d stay put in 2016 – and a wonderful scene of her present-day visit to a medieval church illustrates this. Moreover, Alison’s attempts to locate the past via modern clues demonstrate how much the past remains with us. There were traces of history everywhere: in street names, on inn signs, in old tracks and ancient hedgerows, buried walls and tumbled gravestones. Scratch the surface and it was there.

The Phantom Tree is a skillfully written multi-stranded mystery with thoughtful reflections on two women’s quests for belonging. Read it not only for its evocation of the 16th century but for greater appreciation of the conveniences and freedoms we take for granted today.

The Phantom Tree was published by HarperCollins UK's HQ imprint on 29 December (£7.99, paperback). Thanks to the publisher for approving my NetGalley access; this is the second stop on the book's blog tour.

Published on January 10, 2017 05:00

January 8, 2017

Shortlist for the 2016 Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction

This afternoon, the Langum Charitable Trust announced the eight novels on the 2016 shortlist for the David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction. From the press release, they are:

Barkskins, by Annie Proulx (Scribner)

Champion of the World, by Chad Dundas (Putnam)

The Cigar Factory: A Novel of Charleston, by Michele Moore (Univ. of South Carolina Press)

Exile on Bridge Street, by Eamon Loingsign (Three Rooms Press)

Fates and Traitors: A Novel of John Wilkes Booth, by Jennifer Chiaverini (Dutton)

A Friend of Mr. Lincoln , by Stephen Harrigan (Knopf)

Ginny Gall, by Charlie Smith (Harper)

I Will Send Rain , by Rae Meadows (Henry Holt)

How many have you read? I've read two, and the links above go to the reviews on my site.

The 2016 winner and finalist will be announced in about a month. For more details on the prize, see the Langum Charitable Trust. To submit a novel for consideration, view the directions available at the site. The readers' guidelines for the prize may also be of interest.

The prize is awarded annually to the "best book in American historical fiction that is both excellent fiction and excellent history." Last year's winner was Faith Sullivan's Good Night, Mr. Wodehouse (Milkweed Editions). See the site for details on previous winners and finalists.

Barkskins, by Annie Proulx (Scribner)

Champion of the World, by Chad Dundas (Putnam)

The Cigar Factory: A Novel of Charleston, by Michele Moore (Univ. of South Carolina Press)

Exile on Bridge Street, by Eamon Loingsign (Three Rooms Press)

Fates and Traitors: A Novel of John Wilkes Booth, by Jennifer Chiaverini (Dutton)

A Friend of Mr. Lincoln , by Stephen Harrigan (Knopf)

Ginny Gall, by Charlie Smith (Harper)

I Will Send Rain , by Rae Meadows (Henry Holt)

How many have you read? I've read two, and the links above go to the reviews on my site.

The 2016 winner and finalist will be announced in about a month. For more details on the prize, see the Langum Charitable Trust. To submit a novel for consideration, view the directions available at the site. The readers' guidelines for the prize may also be of interest.

The prize is awarded annually to the "best book in American historical fiction that is both excellent fiction and excellent history." Last year's winner was Faith Sullivan's Good Night, Mr. Wodehouse (Milkweed Editions). See the site for details on previous winners and finalists.

Published on January 08, 2017 13:22

January 5, 2017

Janet MacLeod Trotter's The Girl from the Tea Garden, set at the end of the British Raj

Janet MacLeod Trotter has been one of my favorite writers of regional sagas. She’s especially adept at delving into the lives of the working-class men and women of England’s industrial North East. Among other works, she transformed the stories of Catherine Cookson’s grandmother, mother, and Catherine herself into gripping biographical fiction (I reviewed Return to Jarrow in 2009). Her books were the only historical novels I saw for sale at the Beamish Open Air Museum when I visited there a few years ago.

Janet MacLeod Trotter has been one of my favorite writers of regional sagas. She’s especially adept at delving into the lives of the working-class men and women of England’s industrial North East. Among other works, she transformed the stories of Catherine Cookson’s grandmother, mother, and Catherine herself into gripping biographical fiction (I reviewed Return to Jarrow in 2009). Her books were the only historical novels I saw for sale at the Beamish Open Air Museum when I visited there a few years ago. Trotter’s latest books, the India Tea series, are based on her grandparents’ diaries and letters from when they lived in India in the 1920s-40s, and there’s some cross-pollination with her familiar English settings as the characters travel back and forth. The Girl from the Tea Garden is third after The Tea Planter’s Daughter and The Tea Planter’s Bride, which I haven’t read yet, but I’ve never minded arriving mid-way into a series. Enough background was provided for everything to make sense.

The heroine is Adela Robson, who’s an adolescent schoolgirl as the novel opens in 1933. The story follows her through the WWII years as she struggles for acceptance in a world that looks down on those of Anglo-Indian heritage (her maternal great-grandmother was an Assamese woman). Also, as a beautiful young would-be actress, Adela must also look past all of society’s distractions, which include a handsome playboy prince, to find her way back to the people and qualities she values most.

Adela develops a crush on steamboat captain Sam Jackman early on, after she sneaks a ride in his car while fleeing her hated boarding school on her way home to her family’s tea plantation at Belgooree. Her feelings are returned after she grows into adulthood. I liked Sam a lot. The survivor of a troubled childhood, Sam is a decent sort who gets things done but doesn’t crave attention for his honorable deeds. He also makes plain that Britain’s departure from India is inevitable and works toward this ultimate goal – although he feels he can’t be tied down emotionally to accomplish this. There were many times I found myself wishing for greater emphasis on Sam’s experiences and less on Adela’s flirtations and performances; there were also many side-stories, such as one involving a young Indian woman’s desperate plight, that I wished were pursued further. Also, in one instance in particular, Adela comes across as impossibly naïve.

Adela’s emotional journey is emphasized, and has some powerful moments, particularly when she travels to visit relatives in Tyneside and is faced with a life-changing decision. I found the novel strongest in its depictions of complex family relationships and India’s alluring scenery, from the noise and color of the jungle to the wooded hills of Simla. Although I would have preferred greater focus on the many social issues facing India at the time, as a star-crossed love story, the novel works well.

The Girl from the Tea Garden was published by Amazon's Lake Union imprint in December 2016; I read it from a NetGalley copy.

Published on January 05, 2017 05:00

December 31, 2016

Some highlights from a year of reading - 2016

I debated whether to post a list of 2016 favorites. Choosing from among those I'd read in the last year proved challenging, and I spent way too much time dithering over a list. In the end, I decided I'd already made my decisions via Goodreads, so I should stick to it.

Goodreads has a nice display of my 2016 Year in Books. I didn't meet my challenge of 100 books read, instead getting to just 94 (Goodreads says 89, but I didn't track manuscripts I'd read for friends, which aren't in the system anyway, or books I'd read as an award judge). For my choices on which to highlight in this post, I counted only books first published in 2016.

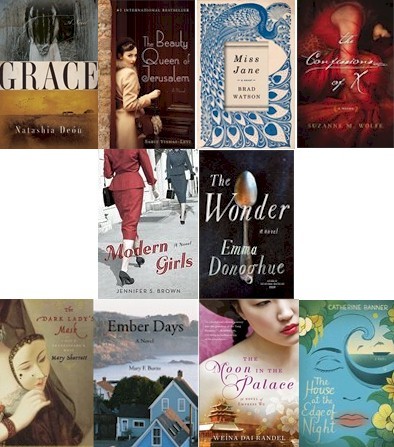

Okay, enough disclaimers. Here are the 10 books I'd rated as five-star reads in 2016, arranged in no particular order.

Natashia Deón, Grace - A deeply affecting novel about motherhood and freedom in the antebellum South, as seen from the viewpoint of an enslaved woman murdered just after her daughter's birth. Brave, unflinching, and memorable.

Sarit Yishai-Levi, The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem - This debut novel from an Israeli author became an international bestseller in its original Hebrew. It involved me fully in the daily lives, hopes, and sufferings of four generations of Sephardi Jewish women in 20th-century Jerusalem.

Brad Watson, Miss Jane - A beautifully contemplative novel about a woman from early 20th-century Mississippi (based on the author's great-aunt) who was born with an unusual medical condition that precludes marriage but seizes what joy she can from life all the same.

Suzanne Wolfe, The Confessions of X - This imagined autobiography of the unnamed mistress of Augustine of Hippo is a poetic work of art, literary historical fiction set during an age -- the shadowy fourth century AD -- about which few historical novels are written.

Jennifer S. Brown, Modern Girls - In this warmhearted yet realistic novel, an immigrant mother and her Americanized daughter in 1930s NYC both find themselves unhappily pregnant. It's full of wonderful details on Jewish life and customs at the time.

Emma Donoghue, The Wonder - In 1859, an English nurse travels to rural Ireland to investigate the case of a "fasting girl" and discovers a potential crime-in-progress. Devout Catholicism mixes with folk superstition in my vote for the most affecting, suspenseful read of the year.

Mary Sharratt, The Dark Lady's Mask - The imagined relationship between English poet Aemilia Lanyer and William Shakespeare; the author always has insightful things to say about historical women's roles and accomplishments.

Mary F. Burns, Ember Days - On the cusp of the 1960s, life-changing secrets emerge among the residents of the small coastal town of Mendocino, California. There are many characters and viewpoints, all distinct, and their religious beliefs, carefully interwoven without preachiness, allow for an abiding sense of hope.

Weina Dai Randel, The Moon in the Palace - This debut novel about the younger years of the future Empress Wu presents a young girl's transition into womanhood at the imperial court of 7th-century China. Far from a standard tale of royal intrigue, the writing provides entrance into a formal yet sumptuous world.

Catherine Banner, The House on the Edge of Night - A near century-spanning epic set on the fictional isle off the Sicilian coast, Banner's debut novel combines the lively style of a folk tale with the realism of a meaty historical saga. I found it engrossing and would love to visit Castellamare in person.

And there we have it, with just six hours to spare until the New Year. Thanks very much for following this site, and I hope the next year will bring you lots of good reading!

Goodreads has a nice display of my 2016 Year in Books. I didn't meet my challenge of 100 books read, instead getting to just 94 (Goodreads says 89, but I didn't track manuscripts I'd read for friends, which aren't in the system anyway, or books I'd read as an award judge). For my choices on which to highlight in this post, I counted only books first published in 2016.

Okay, enough disclaimers. Here are the 10 books I'd rated as five-star reads in 2016, arranged in no particular order.

Natashia Deón, Grace - A deeply affecting novel about motherhood and freedom in the antebellum South, as seen from the viewpoint of an enslaved woman murdered just after her daughter's birth. Brave, unflinching, and memorable.

Sarit Yishai-Levi, The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem - This debut novel from an Israeli author became an international bestseller in its original Hebrew. It involved me fully in the daily lives, hopes, and sufferings of four generations of Sephardi Jewish women in 20th-century Jerusalem.

Brad Watson, Miss Jane - A beautifully contemplative novel about a woman from early 20th-century Mississippi (based on the author's great-aunt) who was born with an unusual medical condition that precludes marriage but seizes what joy she can from life all the same.

Suzanne Wolfe, The Confessions of X - This imagined autobiography of the unnamed mistress of Augustine of Hippo is a poetic work of art, literary historical fiction set during an age -- the shadowy fourth century AD -- about which few historical novels are written.

Jennifer S. Brown, Modern Girls - In this warmhearted yet realistic novel, an immigrant mother and her Americanized daughter in 1930s NYC both find themselves unhappily pregnant. It's full of wonderful details on Jewish life and customs at the time.

Emma Donoghue, The Wonder - In 1859, an English nurse travels to rural Ireland to investigate the case of a "fasting girl" and discovers a potential crime-in-progress. Devout Catholicism mixes with folk superstition in my vote for the most affecting, suspenseful read of the year.

Mary Sharratt, The Dark Lady's Mask - The imagined relationship between English poet Aemilia Lanyer and William Shakespeare; the author always has insightful things to say about historical women's roles and accomplishments.

Mary F. Burns, Ember Days - On the cusp of the 1960s, life-changing secrets emerge among the residents of the small coastal town of Mendocino, California. There are many characters and viewpoints, all distinct, and their religious beliefs, carefully interwoven without preachiness, allow for an abiding sense of hope.

Weina Dai Randel, The Moon in the Palace - This debut novel about the younger years of the future Empress Wu presents a young girl's transition into womanhood at the imperial court of 7th-century China. Far from a standard tale of royal intrigue, the writing provides entrance into a formal yet sumptuous world.

Catherine Banner, The House on the Edge of Night - A near century-spanning epic set on the fictional isle off the Sicilian coast, Banner's debut novel combines the lively style of a folk tale with the realism of a meaty historical saga. I found it engrossing and would love to visit Castellamare in person.

And there we have it, with just six hours to spare until the New Year. Thanks very much for following this site, and I hope the next year will bring you lots of good reading!

Published on December 31, 2016 15:50

December 27, 2016

Historical fiction paperback makeovers, part two

I always like examining and discussing historical novel cover art. The following ten pairings include the hardcover jacket design and the corresponding cover redesign for the paperback (mostly from 2016, with a couple from 2015). In most cases, the books are considered literary fiction, and the images reflect this: they're elegant, bold, dramatic, and original. The paperbacks incorporate the novels' themes while conveying a more approachable feel, with the increased usage of human figures and readily identifiable tropes. Dictator, for instance, uses a look that implies "ancient-world historical adventure." That's my impression, anyway. What do you think of these makeovers?

Part 1 in this series, from August 2015, can be seen here.

Elizabeth, New Jersey, during one tragedy-filled season in the 1950s.

Elizabeth, New Jersey, during one tragedy-filled season in the 1950s.

The Biblical story of King David, as seen from multiple viewpoints.

The Biblical story of King David, as seen from multiple viewpoints.

A female pugilist's story in Georgian Britain.

A female pugilist's story in Georgian Britain.

Third and final novel in the Cicero trilogy, set in ancient Rome.

Third and final novel in the Cicero trilogy, set in ancient Rome.

The lives of wealthy expatriates Sara and Gerald Murphy on the French Riviera in the 1920s.

The lives of wealthy expatriates Sara and Gerald Murphy on the French Riviera in the 1920s.

The lives in a family of mixed faith (Jewish-Christian) in Berlin during

The lives in a family of mixed faith (Jewish-Christian) in Berlin during

the WWI years and Jazz Age.

The fateful voyage of the Hindenburg in 1937, from the viewpoint of its passengers.

The fateful voyage of the Hindenburg in 1937, from the viewpoint of its passengers.

The relationship between sisters Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.

The relationship between sisters Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.

A multi-generational saga about a Jewish family, set along the Connecticut

A multi-generational saga about a Jewish family, set along the Connecticut

shoreline in the 1940s.

The story of Loretta Young and Clark Gable during Hollywood's Golden Age.

The story of Loretta Young and Clark Gable during Hollywood's Golden Age.

Part 1 in this series, from August 2015, can be seen here.

Elizabeth, New Jersey, during one tragedy-filled season in the 1950s.

Elizabeth, New Jersey, during one tragedy-filled season in the 1950s. The Biblical story of King David, as seen from multiple viewpoints.

The Biblical story of King David, as seen from multiple viewpoints. A female pugilist's story in Georgian Britain.

A female pugilist's story in Georgian Britain. Third and final novel in the Cicero trilogy, set in ancient Rome.

Third and final novel in the Cicero trilogy, set in ancient Rome. The lives of wealthy expatriates Sara and Gerald Murphy on the French Riviera in the 1920s.

The lives of wealthy expatriates Sara and Gerald Murphy on the French Riviera in the 1920s. The lives in a family of mixed faith (Jewish-Christian) in Berlin during

The lives in a family of mixed faith (Jewish-Christian) in Berlin during the WWI years and Jazz Age.

The fateful voyage of the Hindenburg in 1937, from the viewpoint of its passengers.

The fateful voyage of the Hindenburg in 1937, from the viewpoint of its passengers.  The relationship between sisters Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.

The relationship between sisters Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.  A multi-generational saga about a Jewish family, set along the Connecticut

A multi-generational saga about a Jewish family, set along the Connecticut shoreline in the 1940s.

The story of Loretta Young and Clark Gable during Hollywood's Golden Age.

The story of Loretta Young and Clark Gable during Hollywood's Golden Age.

Published on December 27, 2016 16:00

December 21, 2016

Aimie K. Runyan's Duty to the Crown, second in a saga of early French Canada

In my review of the first book in Aimie K. Runyan’s trilogy about the women of New France’s Quebec settlement in the 17th century, Promised to the Crown, I’d written that “the latter part of the book appears to head into saga territory.” This turned out to be a good prediction for the second book, Duty to the Crown. It opens in 1677, about half a generation later, and focuses on three women of very different upbringing, and who aren’t particularly close, but who are drawn together as their circumstances change.

In my review of the first book in Aimie K. Runyan’s trilogy about the women of New France’s Quebec settlement in the 17th century, Promised to the Crown, I’d written that “the latter part of the book appears to head into saga territory.” This turned out to be a good prediction for the second book, Duty to the Crown. It opens in 1677, about half a generation later, and focuses on three women of very different upbringing, and who aren’t particularly close, but who are drawn together as their circumstances change. Manon Lefebvre, a young Huron woman who had been raised as a foster daughter in a well-to-do colonial household, had returned to her home village but must reinvent her life after she’s suddenly expelled from it. The painful realities of a woman’s lot in this French frontier community are exemplified through the story of Gabrielle Giroux. A talented seamstress who had escaped a rough family environment, she marries a stranger to save her guardians the large fine they’d incur if she doesn’t find a husband by age sixteen. Lastly, Claudine Deschamps, Manon’s spoiled foster sister and the younger sister of Nicole from the first book, undergoes trials that transform her character.

The story excels at depicting the women’s emotional growth over the novel’s three-year span. They rely on one another for support when men or the law abandons them to their fates, which happens quite often. It’s made clear how directly their happiness, or lack thereof, is tied to the men they wed. In a close-knit community like Quebec, an unmarried woman can lose her good reputation after one thoughtless act, while a Rouen farmer’s daughter can become very wealthy and gain social status through her marriage to a local seigneur. By now, the women and their families aren’t new immigrants, but settlers who think of Quebec as their home, and their mindset reflects that.

The larger political and economic events shaping French Canada aren’t as prominent as they were in the first book; the settlers’ world seems very self-contained. However, the author strikes a good balance among the lives of the colonial elite, with their richly appointed homes and gowns, and those of average settlers and the Huron peoples. This lively and entertaining saga is written with a light touch. The women’s domestic concerns are paramount, and the joys and misfortunes they experience are evoked in an affecting way. I felt personally involved in their lives and am eager to see where their families’ stories lead from here.

Duty to the Crown was published by Kensington in November.

Published on December 21, 2016 10:29

December 14, 2016

Best of historical fiction lists from various venues

'Tis that time of year when "best of" lists are appearing at different bookish sites. Many such lists exist, but most don't divide the books by genre, or if they do, historical fiction isn't one of them. There are a few I've found, though, that include a category for historical novels. Am I missing any others?

'Tis that time of year when "best of" lists are appearing at different bookish sites. Many such lists exist, but most don't divide the books by genre, or if they do, historical fiction isn't one of them. There are a few I've found, though, that include a category for historical novels. Am I missing any others?The 2016 Goodreads Choice Award for Historical Fiction went to Colson Whitehead's The Underground Railroad, a worthy choice. There are a few neat things about this list. First, the voting is open to everyone with a Goodreads account. Second, you can see how many votes the winner and nominees received. Third, the end result makes for a nice mixture of literary and genre fiction, for those who categorize books that way. Fourth, for me personally, it's always one of the few prizes (if not the only one) where I've actually read a number of the nominees.

It helps that there are 20 altogether, and I've read five: in addition to The Underground Railroad , there's Emma Donoghue's The Wonder , Weina Dai Randel's The Moon in the Palace , Kathleen Grissom's Glory Over Everything , and Jennifer S. Brown's Modern Girls .

Next, NPR's Book Concierge, their guide to 2016's great reads, gathers all of the books tagged "historical fiction" in a gallery of covers. Both adult books and YAs are included. The Wonder is included here too, along with Rose Tremain's The Gustav Sonata. There are a few here I've never heard of before and look like potentials for the TBR.

Library Journal 's Best Genre Fiction selections include a Historical Fiction category, with five books chosen. Among these, the only one I've read is Natashia Deon's Grace, which I agree belongs on a top 5 list.

Addendum: thanks to my Bloglovin feed, I just found one more. Booktopia, an Australian bookstore, has a six-book shortlist for the best historical fiction reads of the year, as well as the winner, Melissa Ashley's The Birdman's Wife. And some of the books on their lists for literary and popular fiction are historical, too.

Published on December 14, 2016 15:20

December 11, 2016

To Capture What We Cannot Keep by Beatrice Colin, a literary love story set in Belle Époque Paris

They meet while aloft in a hot air balloon over Paris in 1887. Caitriona Wallace is an impoverished Glaswegian widow acting as chaperone to the wealthy Arrol siblings as they travel Europe on their Grand Tour. One of Gustave Eiffel’s engineers, Émile Nouguier needs to marry among his class to please his mother and bolster the family finances.

They meet while aloft in a hot air balloon over Paris in 1887. Caitriona Wallace is an impoverished Glaswegian widow acting as chaperone to the wealthy Arrol siblings as they travel Europe on their Grand Tour. One of Gustave Eiffel’s engineers, Émile Nouguier needs to marry among his class to please his mother and bolster the family finances.Although Alice Arrol is a naive teenager, she’s a potential match for Émile, but he finds himself more intrigued by Cait. However, in returning his affections, Cait would be choosing passion over honor.

Their beautifully restrained love story, told in a refreshingly unhurried manner and grounded in the era’s social constraints, gains complexity as Alice and her brother, Jamie, rebel against their expected roles. Nouguier is a historical figure, and readers get a close-up perspective on the Eiffel Tower’s step-by-step construction.

Drawn with care and suffused with stylish ambiance, Colin’s (The Glimmer Palace, 2008) Paris is a city of painters, eccentric aristocrats, desperate prostitutes, secret lovers, and the magnificent artistic vision taking shape high above them. Devotees of the Belle Époque should relish it.

To Capture What We Cannot Keep was published by Flatiron Books in late November (hardcover, 304pp, $25.99). This review first appeared in Booklist's 10/1 issue.

There are two other things I should say explicitly about this book: it's a work of historical literary fiction, and although a love story forms an important part of the plot, it's not a romance by genre. Readers expecting more of a traditional romance will likely find the pacing too slow for their tastes. Also, as with other literary novels, the characterizations are complex, subtle, and multi-layered. The cover is great and fitting, but the title doesn't really do it for me. It feels like it was chosen to appeal to the many fans of All the Light We Cannot See.

Published on December 11, 2016 06:12

December 5, 2016

Historical novels by Australian women writers for #AWW2016, and on to 2017

I'm wrapping up my second year of participation in the Australian Women Writers Challenge. Now that I'm part of the associated Facebook group, I'm seeing the impressive reading accomplishments of the other participants, which far surpass mine, but I'm pleased to have met my 2016 goal of six books read, four reviewed. I reviewed all six, which are as follows:

I'm wrapping up my second year of participation in the Australian Women Writers Challenge. Now that I'm part of the associated Facebook group, I'm seeing the impressive reading accomplishments of the other participants, which far surpass mine, but I'm pleased to have met my 2016 goal of six books read, four reviewed. I reviewed all six, which are as follows:The Wife's Tale by Christine Wells, a dual-time romance/mystery set in modern and Georgian England.

The Memory Stones by Caroline Brothers, literary fiction about what happens to an Argentine family during the country's Dirty War.

Call to Juno by Elisabeth Storrs, the final book in her trilogy set in ancient Rome and Etruria.

The Railwayman's Wife by Ashley Hay, a literary novel about the aftermath of loss, set in the Australian seaside town of Thirroul beginning in 1948.

Daughter of Albion by Ilka Tampke, a gritty historical fantasy set in first-century England. In the UK and Australia, the title is Skin.

And the final review was for a book-length literary study on the historical fiction genre by Gillian Polack, History and Fiction: Writers, Their Research, Worlds, and Stories, which I reviewed for the nonfiction section of November's Historical Novels Review.

Thinking about it, I'm realizing I actually read seven that fit. The one which I didn't review (because I read it on vacation) was Barbara Hannay's The Secret Years, which uses the popular multi-era format to tell the story of a north Queensland family from WWII to the present. It used to be on sale for Kindle in the US but isn't any longer.

I've also signed up again for 2017; I have plenty of books by Australian women writers waiting on my physical and virtual shelves to be read. I'm especially eager to get my hands on Lucy Treloar's Salt Creek, which finally came back in stock at Fishpond. With everything I'm assigned to read by various publications, I'm not sure if I can make it past my 2016 goal, but we'll see.

Published on December 05, 2016 15:00