Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 73

February 16, 2017

The Johnstown Girls by Kathleen George, fiction about the 1889 Johnstown Flood, women's lives, and family secrets

“Is a hundred years long enough to keep a secret?”

A novel that mingles past reminiscences with a contemporary storyline, The Johnstown Girls centers on the traumatic flood that devastated the village of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in 1889, killing over 2200 people.

A novel that mingles past reminiscences with a contemporary storyline, The Johnstown Girls centers on the traumatic flood that devastated the village of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in 1889, killing over 2200 people.

One of the fortunate survivors of the disaster, Ellen Emerson is a spry 103-year-old in the year 1989. Although her parents and brother were lost to the floodwaters, Ellen miraculously stayed alive after a mattress bearing her and her twin sister swept them both to safety. Or so Ellen continues to believe. The siblings were separated in the chaos, and young Mary’s body was never found.

To mark the centennial of the event, Nina Collins and Ben Braddock, two reporters from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, arrive at Ellen’s home to interview her. Ben’s editor wants him to dig up some new angle on her story. The pair succeed in doing so, but the research process takes some unexpected turns.

Ellen and her long, eventful life are the highlights, and the sections recounting her perspective are easily the most riveting. Both natives of Johnstown, Ellen and Nina develop a warm friendship that comes alive on the page. Ellen tells her long-hidden secret to Nina and Ben early on, so it doesn’t drive the plot, but the details on her life as a career woman in big-city and small-town America easily hold readers’ attention. The aspects involving Nina and Ben’s romance just can’t compare, plus it has odd emphases and digressions. There’s an explicit sex scene in the first few pages, when we barely know the characters – why? Do we need to be brought into a marriage counseling session between Ben and his estranged wife? In addition, the story occasionally slips into other viewpoints (like that of Nina’s mother) that don’t feel necessary.

The novel offers a wealth of information for anyone interested in the Johnstown Flood, the circumstances that caused it, and its effect on the region and its residents a century later. Just be prepared to put up with some meanderings and quirks along the way.

The Johnstown Girls was published in paperback by the University of Pittsburgh Press last week ($18.95, 348pp). This is a long overdue review, which I based on a NetGalley copy from 2014, which is when the hardcover edition appeared.

A novel that mingles past reminiscences with a contemporary storyline, The Johnstown Girls centers on the traumatic flood that devastated the village of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in 1889, killing over 2200 people.

A novel that mingles past reminiscences with a contemporary storyline, The Johnstown Girls centers on the traumatic flood that devastated the village of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in 1889, killing over 2200 people. One of the fortunate survivors of the disaster, Ellen Emerson is a spry 103-year-old in the year 1989. Although her parents and brother were lost to the floodwaters, Ellen miraculously stayed alive after a mattress bearing her and her twin sister swept them both to safety. Or so Ellen continues to believe. The siblings were separated in the chaos, and young Mary’s body was never found.

To mark the centennial of the event, Nina Collins and Ben Braddock, two reporters from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, arrive at Ellen’s home to interview her. Ben’s editor wants him to dig up some new angle on her story. The pair succeed in doing so, but the research process takes some unexpected turns.

Ellen and her long, eventful life are the highlights, and the sections recounting her perspective are easily the most riveting. Both natives of Johnstown, Ellen and Nina develop a warm friendship that comes alive on the page. Ellen tells her long-hidden secret to Nina and Ben early on, so it doesn’t drive the plot, but the details on her life as a career woman in big-city and small-town America easily hold readers’ attention. The aspects involving Nina and Ben’s romance just can’t compare, plus it has odd emphases and digressions. There’s an explicit sex scene in the first few pages, when we barely know the characters – why? Do we need to be brought into a marriage counseling session between Ben and his estranged wife? In addition, the story occasionally slips into other viewpoints (like that of Nina’s mother) that don’t feel necessary.

The novel offers a wealth of information for anyone interested in the Johnstown Flood, the circumstances that caused it, and its effect on the region and its residents a century later. Just be prepared to put up with some meanderings and quirks along the way.

The Johnstown Girls was published in paperback by the University of Pittsburgh Press last week ($18.95, 348pp). This is a long overdue review, which I based on a NetGalley copy from 2014, which is when the hardcover edition appeared.

Published on February 16, 2017 10:00

February 14, 2017

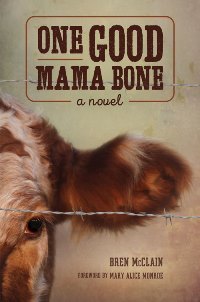

Writing the Past: The Family Story Behind One Good Mama Bone, a guest post by Bren McClain

Author Bren McClain is here today with the moving family story that inspired her debut novel, as well as details on the research she conducted to make her novel's world feel authentic to the place, period, and characters.

~

Writing the Past:

The Family Story Behind One Good Mama BoneBren McClain

Understand this first – my daddy was a crusty, old-fashioned, Southern Baptist farmer in Anderson, South Carolina. He drew his life, all 89 years, from the land. Dirt ran in his blood. Be his little girl and find something funny while eating supper, start to giggle, and he’ll stop you cold and yell down in your bones, “You’re supposed to eat when you come to the eating table.”

Understand this first – my daddy was a crusty, old-fashioned, Southern Baptist farmer in Anderson, South Carolina. He drew his life, all 89 years, from the land. Dirt ran in his blood. Be his little girl and find something funny while eating supper, start to giggle, and he’ll stop you cold and yell down in your bones, “You’re supposed to eat when you come to the eating table.”

Yet, ask him about this one day in March of 1941 when he was a fourteen-year-old boy, a photograph of him and his 4-H steer splashed above the fold and across the front page of his hometown newspaper, The Anderson Independent, and hear what he tells you. “Get your mind on something else,” his voice no longer yelling, but soft like it could break. Read the story below the photograph and find out the event is called The Fat Cattle Show & Sale and that my daddy’s steer, weighing in at 1100 pounds, was named Grand Champion. For that, he received 30 cents a pound, which totaled $330. He was a celebrity, of sorts, treated to free lunches all over town. Look back at him now, and see his eyes misted over.

[Click to see larger version in new window]

[Click to see larger version in new window]

I had to find out why.

I wrote a novel, placed in it an innocent six-year-old boy, who enters the Fat Cattle Show & Sale for the big money it would bring him and his mama, if he won. The boy’s father has died, and the farm they live on is in danger of being foreclosed. They’re so poor, he’s lucky if he gets a pear to last him the whole day. I also placed in it another little boy, this one not so innocent, because his daddy forces him to enter, all for the glory of it.

But first, I had a ton of research to do. I chose to set the story in the early 1950s vs. the 1940s, because it better suited the story I was trying to tell. I wanted to give my antagonist, Luther Dobbins, enough time to establish a dynasty with his elder son’s long streak of winning, only for his son to age out and toss the family baton to his younger son. Let’s just say that the folks in the South Carolina Room at the local library got to know me. I put countless hours in front of a microfilm machine, where I fed in reels of The Anderson Independent and rolls and rolls of dimes for copying. Thursday papers were always terrific with their extensive grocery store advertisements that showed the prices of food and the name brands. One day, I ran across an advertisement for a product called “Retonga,” a tonic that I learned women, especially, drank back them, many for its high alcohol content (about one-third). I knew instantly that one of my characters, Mildred, the wife of the antagonist, would make a habit of consuming this liquid.

But the “find” that I loved to pieces was a notice of a weekly event in Anderson called “Shoe of the Week,” sponsored by Welborn Shoes, where women would visit the store, drop their name and telephone number into a box beside a featured shoe and then wait on Friday mornings for a call from WAIM Radio announcer, Marshall Gaillard, who would draw one name from the box. The lucky winner would get that shoe in her size. I gave this wonderful happening to my protagonist, Sarah Creamer, because I wanted something good for her and because shoes already were important in the story.

It was not only the time period that I needed to research, but also cows and the Fat Cattle event itself. Fortunate for me, every Monday, the paper carried a column by the county agent, H. D. Marett, called “Your County Agent Says.” I learned about the kind of grass to plant in pastures, when to put the steers on full feed, the best kind of grain mix, etc.

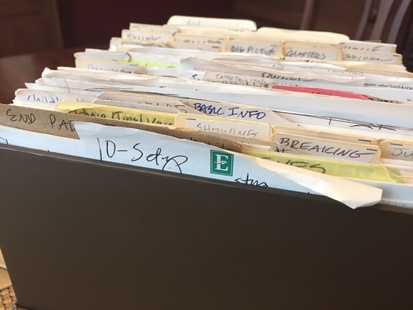

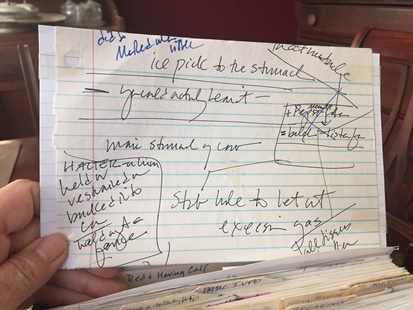

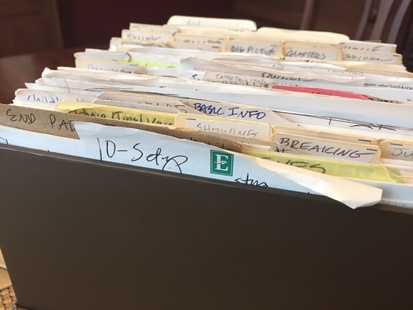

What did I do with all of this research? I organized it into 32 categories - for example, picking out a steer, feeding out a steer, cow biology and also by my character’s names. It was still too much to manage, so I cut out the salient information from each piece of paper, taped the info to 5 X 7 notecards and then organized them with tabs inside a box.

But the most important source of my research was my daddy. He finally came around to my writing this novel. In fact, I’d call him up on the phone and say, “I’ve got another question for you.” His answer? “Shoot.” That meant go ahead. I have a tab called Daddy’s Info. The brands of chewing tobacco, when the road in front of his house was paved, how to fit a burlap bag onto the down chute of a hammermill, how to crank a tractor with a flywheel, how to build a fence using cedar trees, how to kill a hog, the kinds of pistols.

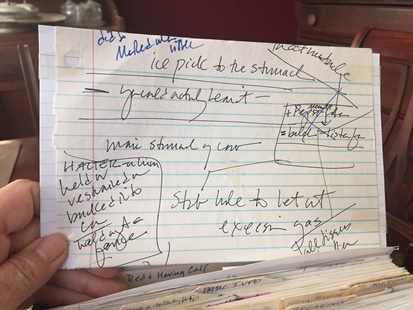

And this one: What to do if a steer gets the bloat.

He had a steer with that condition once, when he was a boy, the animal bloating from eating too much grain. “You can try giving him a Pepsi Cola or two to see if it helps, but if it don’t, you’ll have to stab his stomach with an ice pick.” He talked of the triangular area between the animal’s hip bone and last rib, high up on its left side. “Rub your flat hand over it in little circles and get it all loosened up and then stab it right quick. And if you’ll put your ear right out from the hole, you’ll hear a little whistle when the gas starts to come out.” I followed daddy’s directions entirely when I wrote that scene.

Go back now and look at that first photograph and see the man wearing a hat standing behind the steer. Read the caption beneath and learn this is Bailey Trammel, manager of Ideal Super Market, “where the premium meat will be sold.” Therein lies the answer I had come seeking. Daddy had sold out his best friend, his steer. And I would come to know by reading about other boys, that he had spent a long year with his steer, feeding him, taming him, loving him. “Get your mind on something else,” he had told me.

But I couldn’t. I wrote a novel.

~

Bren McClain's One Good Mama Bone is published by Story River Books of the University of South Carolina Press today. Read more about the novel at the author's website.

~

Writing the Past:

The Family Story Behind One Good Mama BoneBren McClain

Understand this first – my daddy was a crusty, old-fashioned, Southern Baptist farmer in Anderson, South Carolina. He drew his life, all 89 years, from the land. Dirt ran in his blood. Be his little girl and find something funny while eating supper, start to giggle, and he’ll stop you cold and yell down in your bones, “You’re supposed to eat when you come to the eating table.”

Understand this first – my daddy was a crusty, old-fashioned, Southern Baptist farmer in Anderson, South Carolina. He drew his life, all 89 years, from the land. Dirt ran in his blood. Be his little girl and find something funny while eating supper, start to giggle, and he’ll stop you cold and yell down in your bones, “You’re supposed to eat when you come to the eating table.” Yet, ask him about this one day in March of 1941 when he was a fourteen-year-old boy, a photograph of him and his 4-H steer splashed above the fold and across the front page of his hometown newspaper, The Anderson Independent, and hear what he tells you. “Get your mind on something else,” his voice no longer yelling, but soft like it could break. Read the story below the photograph and find out the event is called The Fat Cattle Show & Sale and that my daddy’s steer, weighing in at 1100 pounds, was named Grand Champion. For that, he received 30 cents a pound, which totaled $330. He was a celebrity, of sorts, treated to free lunches all over town. Look back at him now, and see his eyes misted over.

[Click to see larger version in new window]

[Click to see larger version in new window]I had to find out why.

I wrote a novel, placed in it an innocent six-year-old boy, who enters the Fat Cattle Show & Sale for the big money it would bring him and his mama, if he won. The boy’s father has died, and the farm they live on is in danger of being foreclosed. They’re so poor, he’s lucky if he gets a pear to last him the whole day. I also placed in it another little boy, this one not so innocent, because his daddy forces him to enter, all for the glory of it.

But first, I had a ton of research to do. I chose to set the story in the early 1950s vs. the 1940s, because it better suited the story I was trying to tell. I wanted to give my antagonist, Luther Dobbins, enough time to establish a dynasty with his elder son’s long streak of winning, only for his son to age out and toss the family baton to his younger son. Let’s just say that the folks in the South Carolina Room at the local library got to know me. I put countless hours in front of a microfilm machine, where I fed in reels of The Anderson Independent and rolls and rolls of dimes for copying. Thursday papers were always terrific with their extensive grocery store advertisements that showed the prices of food and the name brands. One day, I ran across an advertisement for a product called “Retonga,” a tonic that I learned women, especially, drank back them, many for its high alcohol content (about one-third). I knew instantly that one of my characters, Mildred, the wife of the antagonist, would make a habit of consuming this liquid.

But the “find” that I loved to pieces was a notice of a weekly event in Anderson called “Shoe of the Week,” sponsored by Welborn Shoes, where women would visit the store, drop their name and telephone number into a box beside a featured shoe and then wait on Friday mornings for a call from WAIM Radio announcer, Marshall Gaillard, who would draw one name from the box. The lucky winner would get that shoe in her size. I gave this wonderful happening to my protagonist, Sarah Creamer, because I wanted something good for her and because shoes already were important in the story.

It was not only the time period that I needed to research, but also cows and the Fat Cattle event itself. Fortunate for me, every Monday, the paper carried a column by the county agent, H. D. Marett, called “Your County Agent Says.” I learned about the kind of grass to plant in pastures, when to put the steers on full feed, the best kind of grain mix, etc.

What did I do with all of this research? I organized it into 32 categories - for example, picking out a steer, feeding out a steer, cow biology and also by my character’s names. It was still too much to manage, so I cut out the salient information from each piece of paper, taped the info to 5 X 7 notecards and then organized them with tabs inside a box.

But the most important source of my research was my daddy. He finally came around to my writing this novel. In fact, I’d call him up on the phone and say, “I’ve got another question for you.” His answer? “Shoot.” That meant go ahead. I have a tab called Daddy’s Info. The brands of chewing tobacco, when the road in front of his house was paved, how to fit a burlap bag onto the down chute of a hammermill, how to crank a tractor with a flywheel, how to build a fence using cedar trees, how to kill a hog, the kinds of pistols.

And this one: What to do if a steer gets the bloat.

He had a steer with that condition once, when he was a boy, the animal bloating from eating too much grain. “You can try giving him a Pepsi Cola or two to see if it helps, but if it don’t, you’ll have to stab his stomach with an ice pick.” He talked of the triangular area between the animal’s hip bone and last rib, high up on its left side. “Rub your flat hand over it in little circles and get it all loosened up and then stab it right quick. And if you’ll put your ear right out from the hole, you’ll hear a little whistle when the gas starts to come out.” I followed daddy’s directions entirely when I wrote that scene.

Go back now and look at that first photograph and see the man wearing a hat standing behind the steer. Read the caption beneath and learn this is Bailey Trammel, manager of Ideal Super Market, “where the premium meat will be sold.” Therein lies the answer I had come seeking. Daddy had sold out his best friend, his steer. And I would come to know by reading about other boys, that he had spent a long year with his steer, feeding him, taming him, loving him. “Get your mind on something else,” he had told me.

But I couldn’t. I wrote a novel.

~

Bren McClain's One Good Mama Bone is published by Story River Books of the University of South Carolina Press today. Read more about the novel at the author's website.

Published on February 14, 2017 05:00

February 11, 2017

Jennifer Ryan's The Chilbury Ladies' Choir, an uplifting novel of women on the WWII home front

“There’s something bolstering about singing together.” Jennifer Ryan’s charming debut interweaves many women’s voices to create a strong chorus that rings out with heart and the celebration of life.

“There’s something bolstering about singing together.” Jennifer Ryan’s charming debut interweaves many women’s voices to create a strong chorus that rings out with heart and the celebration of life.The story spans barely five months in 1940, but it’s an eventful time for Chilbury, a small Kentish village seven miles from England’s coast. With most men off at war, the vicar disbands the choir, but as with so many other home front duties, Chilbury’s women take up the reins. Their female-only singing ensemble, daring for its time, is successful in more ways than one.

Their stories are told through their writings, and each woman’s account echoes her personality. There’s Mrs. Tilling, a timid widow and nurse worried about her only son in France; Venetia Winthrop of Chilbury Manor, a sophisticated flirt; Kitty, her attention-hungry younger sister; and Edwina Paltry, a conniving midwife. Kitty’s diary entries are fun, since they burst with enthusiasm and teenage melodrama as she dreams about her sister’s longtime suitor and reacts to her changing world.

In letters to her London-based friend, Venetia reveals how her affair with a mysterious artist turns into something more, to her astonishment. Mrs. Tilling’s growing courage to stand up for herself and others will have readers cheering, as will her growing closeness to the burly colonel billeted with her. Edwina’s involvement in a greedy baby-swapping scheme gets soap-opera silly, but her audaciousness never fails to entertain. The fifth and softest voice is that of Sylvie, a Czech Jewish evacuee.

As the village intrigues play out and the Nazi threat reaches England, shattering buildings and lives, shadowy men skulk about in the woods, and the women draw strength from their togetherness. Fans of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society and the TV series Home Fires should put this uplifting, absorbing novel high on their reading lists.

The Chilbury Ladies' Choir is published by Crown this Tuesday, February 14th in hardcover and ebook. The UK publisher is The Borough Press. This review first appeared in February's Historical Novels Review.

Published on February 11, 2017 07:46

February 8, 2017

Late Harvest by Fiona Buckley, an entertaining historical saga of 19th-century Somerset

Fiona Buckley is best known for her Tudor-era mystery series featuring Ursula Blanchard, lady-in-waiting (and more) at the court of the first Queen Elizabeth. Under her real name, Valerie Anand, she has crafted many outstanding historical novels set in various periods of England’s history, including the six-book Bridges Over Time series as well as two linked standalone novels (

The House of Lanyon

and

The House of Allerbrook

) set on Exmoor in Somerset in the 15th and 16th centuries respectively.

Fiona Buckley is best known for her Tudor-era mystery series featuring Ursula Blanchard, lady-in-waiting (and more) at the court of the first Queen Elizabeth. Under her real name, Valerie Anand, she has crafted many outstanding historical novels set in various periods of England’s history, including the six-book Bridges Over Time series as well as two linked standalone novels (

The House of Lanyon

and

The House of Allerbrook

) set on Exmoor in Somerset in the 15th and 16th centuries respectively. In terms of style and focus, her newest historical saga, Late Harvest, belongs in the same category with the latter. It brings together bucolic settings, timeless human dilemmas, epic romance, and dashing adventure (including intrigue surrounding illegal smuggling) reminiscent of the Poldark novels.

The heroine is Peggy Shawe of Foxwell Farm, a freehold on Exmoor in the county of Somerset. In 1860, as an elderly woman, she looks back on a life which her fellow countrymen might call scandalous, but of which she's proud... she has no regrets about her actions. Her main sorrow involves the many years she was forced to spend apart from the man she loved and lost, Ralph Duggan.

In 1800, Peggy is 20 years old, and there’s always been the unspoken understanding that she’d marry James Bright, the younger son from another farming family. Although Peggy and James are childhood friends, she finds him solid but dull. Then Peggy falls in love with Ralph, whose father engages in “free trading” to avoid the excessive import duties on foreign goods. Peggy’s widowed mother strongly objects to their marriage, claiming they’re unsuited: “Farming families should marry into one another. The sea and the land don’t mix.” Ultimately, their future together is thwarted after Ralph’s brother is accused of murder.

Mention is made of the Napoleonic Wars, but specific events don’t intrude much into the story. However, a deep sense of time and place is ever-present in the farmers’ speech patterns, the beautiful descriptions of the heather-covered moorlands and rocky coastline of Somerset, and local men’s actions against government overreach. People’s long-term relationships with the land are emphasized. “It was,” Peggy states, observing the yarn market at Dunster, “as though bygone times still existed, preserved in the things our ancestors had built.”

Many sagas that span this amount of time can have an episodic feel, but Late Harvest is smoothly paced as it follows Peggy’s domestic life and adventures over many decades. The story comes full circle in a satisfying fashion but takes many twists on its way there.

Late Harvest was published by Severn House in hardcover last June ($29.95, 265pp) and will be out in trade paperback in the US a few weeks from now, in March.($17.95). It's also out on Kindle ($9.99). Thanks to the publisher for access via NetGalley.

For those curious about the setting, aside from the painting on the novel's cover, see the Exford page on the Visit Somerset tourism site. Exford is the rural village where the Shawes live, and it's beautiful country.

Published on February 08, 2017 14:00

February 6, 2017

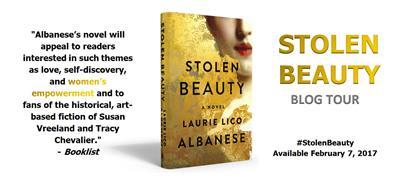

Stolen Beauty by Laurie Lico Albanese, a novel of art and family set in fin-de-siècle and WWII Vienna

For those who moved in high society in fin-de-siècle Vienna, the city sat at the pinnacle of elegance and culture. Provocative political ideas were discussed in private salons and coffeehouses along the Ringstrasse, while painter Gustav Klimt and designers like the Flöge sisters pushed boundaries in art and design.

By four decades later, the Viennese atmosphere was far darker. Amid a rising tide of anti-Semitism, Jews were beaten in the streets, forced out of their homes, and had their property seized by the Nazis, who took care to ensure their heinous methods of theft appeared unimpeachably legal.

In her engrossing tale of art, family, loss, and female empowerment, Laurie Lico Albanese’s Stolen Beauty presents a shifting view of this famous European city. The characters are historical, and the novel also describes a real-life account of long-awaited justice – one that will be familiar to anyone who’s seen the 2015 film Woman in Gold.

In her engrossing tale of art, family, loss, and female empowerment, Laurie Lico Albanese’s Stolen Beauty presents a shifting view of this famous European city. The characters are historical, and the novel also describes a real-life account of long-awaited justice – one that will be familiar to anyone who’s seen the 2015 film Woman in Gold.

I borrowed the DVD of the latter after finishing the book, and they’re quite different, since they focus on different aspects of the history (the past vs. the present). Also, as much as I enjoyed the movie, Helen Mirren’s acting in particular, the book tells a deeper, more fulfilling story.

Alternating as narrators are Adele Bloch-Bauer, who was depicted in multiple works by Gustav Klimt, and her niece Maria Altmann. Their separate stories are fleshed out so well that each could be complete in itself, but the intertwining makes the themes resonate more strongly. Their situations and circumstances strike a marked contrast, but the women are equally brave and determined. Rather than pointing this out in obvious fashion, the author lets readers see this for themselves.

Both women are the youngest daughters in different generations of the same prominent Jewish family. Although neither is religious, this doesn’t matter as far as how society envisions them. While Adele can’t achieve her dream of attending university due to her gender, she makes connections and a name for herself in the avant-garde art world and nourishes her intellect in other ways. Similarly, Maria goes after what she wants, including the husband of her choosing. After being forced to flee the city of her birth for her own survival, Maria, years later, fights to regain the Klimt paintings that the Nazis stole from her family.

Naturally, both women’s stories are intricately intertwined with that of Klimt’s artistic renderings of Adele. Albanese details the circumstances behind their creation, as well as the paintings’ afterlives. Adele’s relationship with Klimt is vividly imagined as an intimate affair that proves beneficial to both; for her, it’s part of her ongoing journey of self-discovery.

Like the gilded image of Adele on canvas, the novel is painted with abundant detail and, in the earlier sections in particular, descriptions that sparkle. For Adele, visiting Vienna’s elegant Central Café with her fiancé for the first time, “the gold-embossed wallpaper made the room glow like a treasure box,” while her new friend Berta Zuckerkandl describes the conversations between writers there: “Sometimes they read aloud to one another, and bits of poetry land on my table like beautiful birds.”

Per the afterword, Stolen Beauty took the author years to research. Read it for insight not only into art and European history, but also the private lives and motivations of two women who stood up for what they believed in.

Stolen Beauty will be published tomorrow in hardcover and ebook by Atria ($26 / $12.99, 320pp). Thanks to the publisher for providing me access via Edelweiss.

This post forms part of the novel's blog tour. As part of the tour, the publisher is offering the opportunity to win one of three signed copies of Stolen Beauty by Laurie Lico Albanese. The contest is open until February 14th. To enter, visit the contest site at Rafflecopter.

By four decades later, the Viennese atmosphere was far darker. Amid a rising tide of anti-Semitism, Jews were beaten in the streets, forced out of their homes, and had their property seized by the Nazis, who took care to ensure their heinous methods of theft appeared unimpeachably legal.

In her engrossing tale of art, family, loss, and female empowerment, Laurie Lico Albanese’s Stolen Beauty presents a shifting view of this famous European city. The characters are historical, and the novel also describes a real-life account of long-awaited justice – one that will be familiar to anyone who’s seen the 2015 film Woman in Gold.

In her engrossing tale of art, family, loss, and female empowerment, Laurie Lico Albanese’s Stolen Beauty presents a shifting view of this famous European city. The characters are historical, and the novel also describes a real-life account of long-awaited justice – one that will be familiar to anyone who’s seen the 2015 film Woman in Gold.I borrowed the DVD of the latter after finishing the book, and they’re quite different, since they focus on different aspects of the history (the past vs. the present). Also, as much as I enjoyed the movie, Helen Mirren’s acting in particular, the book tells a deeper, more fulfilling story.

Alternating as narrators are Adele Bloch-Bauer, who was depicted in multiple works by Gustav Klimt, and her niece Maria Altmann. Their separate stories are fleshed out so well that each could be complete in itself, but the intertwining makes the themes resonate more strongly. Their situations and circumstances strike a marked contrast, but the women are equally brave and determined. Rather than pointing this out in obvious fashion, the author lets readers see this for themselves.

Both women are the youngest daughters in different generations of the same prominent Jewish family. Although neither is religious, this doesn’t matter as far as how society envisions them. While Adele can’t achieve her dream of attending university due to her gender, she makes connections and a name for herself in the avant-garde art world and nourishes her intellect in other ways. Similarly, Maria goes after what she wants, including the husband of her choosing. After being forced to flee the city of her birth for her own survival, Maria, years later, fights to regain the Klimt paintings that the Nazis stole from her family.

Naturally, both women’s stories are intricately intertwined with that of Klimt’s artistic renderings of Adele. Albanese details the circumstances behind their creation, as well as the paintings’ afterlives. Adele’s relationship with Klimt is vividly imagined as an intimate affair that proves beneficial to both; for her, it’s part of her ongoing journey of self-discovery.

Like the gilded image of Adele on canvas, the novel is painted with abundant detail and, in the earlier sections in particular, descriptions that sparkle. For Adele, visiting Vienna’s elegant Central Café with her fiancé for the first time, “the gold-embossed wallpaper made the room glow like a treasure box,” while her new friend Berta Zuckerkandl describes the conversations between writers there: “Sometimes they read aloud to one another, and bits of poetry land on my table like beautiful birds.”

Per the afterword, Stolen Beauty took the author years to research. Read it for insight not only into art and European history, but also the private lives and motivations of two women who stood up for what they believed in.

Stolen Beauty will be published tomorrow in hardcover and ebook by Atria ($26 / $12.99, 320pp). Thanks to the publisher for providing me access via Edelweiss.

This post forms part of the novel's blog tour. As part of the tour, the publisher is offering the opportunity to win one of three signed copies of Stolen Beauty by Laurie Lico Albanese. The contest is open until February 14th. To enter, visit the contest site at Rafflecopter.

Published on February 06, 2017 05:00

February 2, 2017

More historical fiction prize winners - the Langum Prize and the Costa Awards

It's the season for literary prize announcements. The shortlist for the 2016 Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction was posted last month, while the winner and finalist were announced this week.

It's the season for literary prize announcements. The shortlist for the 2016 Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction was posted last month, while the winner and finalist were announced this week.Michele Moore's debut novel The Cigar Factory (Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2016) is the winner of the 2016 Langum Prize.

Per the organizer's comments: "This marvelous debut traces the lives of two working class families in Charleston during the years 1917-1946. The families are similar in many ways: devout and practicing Roman Catholics, headed by matriarchs who work in the local cigar factory, both struggling mightily for survival in severely limited circumstances. Yet they are dissimilar in ways crucial for Charleston in these years: one family is black and the other white... The author describes the difficult lives of these two families, both joys and sorrows, with great sensitivity and beauty."

See also the book's Facebook page for more details. Of interest to book groups: the author is available for discussions via Skype.

More details are posted at the Langum Trust.

~

Also, the Costa Award, a long-running British literary prize open to UK and Irish authors, announced their 2016 Book of the Year on January 31st. The winner happens to be a historical novel: Sebastian Barry's Days Without End (published in the US by Viking in January).

Also, the Costa Award, a long-running British literary prize open to UK and Irish authors, announced their 2016 Book of the Year on January 31st. The winner happens to be a historical novel: Sebastian Barry's Days Without End (published in the US by Viking in January). Days Without End tells the story of young Irishman Thomas McNulty, who crosses the Atlantic in the 1850s, fights in the Civil War, and has an intimate relationship with a fellow soldier.

For background, read The Guardian's interview with the author, in which he reveals how his son "instructed [him] in the magic of gay life."

Another historical novel on the Costa category winner list was Francis Spufford's Golden Hill, set in 1740s New York (First Novel Award). Golden Hill will be published in the US by Scribner this June.

Published on February 02, 2017 16:00

January 31, 2017

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee, an engrossing historical saga of Korean life in 20th-century Japan

Pachinko is a novel that exemplifies the word “epic.” Following the members of a close-knit family from a rural fishing village on a Korean island to various locales in Japan and elsewhere, it spans nearly 90 years and almost 500 pages. I would have been happy if it were longer.

It’s a big story, rich in character and activity. These aspects, plus the clean, straightforward writing style, make for a brisk, absorbing read. It opens in 1910 with the circumstances that lead to the birth of the principal heroine, Sunja, who grows into a sturdily built, handsome young woman.

When a liaison with a wealthy fish broker leaves her pregnant, and Sunja learns he can’t marry her, one of the guests recuperating at her mother’s boardinghouse makes a surprising offer. Due to his frailty, Baek Isak never expected to wed anyone, but his Christian beliefs (he’s a Presbyterian minister from Pyongyang) and generosity of spirit leads him to ask for Sunja’s hand. When the couple relocates to Osaka and moves into Isak’s brother’s home in the Korean ghetto, Sunja views firsthand the plight of immigrants living in a country that doesn’t welcome them.

When a liaison with a wealthy fish broker leaves her pregnant, and Sunja learns he can’t marry her, one of the guests recuperating at her mother’s boardinghouse makes a surprising offer. Due to his frailty, Baek Isak never expected to wed anyone, but his Christian beliefs (he’s a Presbyterian minister from Pyongyang) and generosity of spirit leads him to ask for Sunja’s hand. When the couple relocates to Osaka and moves into Isak’s brother’s home in the Korean ghetto, Sunja views firsthand the plight of immigrants living in a country that doesn’t welcome them.

The novel was revelatory for me, as it introduced me to an aspect of history about which I’d known little. Between 1910 and 1945, Korea was a colony of Japan. Through the experiences of Sunja, her husband, in-laws, and descendants, we get to see the ramifications of this part of history. As one Korean man remarks in the novel, “For people like us, home doesn’t exist.” In Japan, Koreans are negatively stereotyped as belonging to a “cunning and wily tribe” and “natural troublemakers.” They can’t rent decent housing or obtain the best jobs. On the other hand, any Koreans who adapt to Japanese ways would be looked upon suspiciously back home. The members of the Baek family must always be on their best behavior, since they represent their country of origin.

Over the years, through constant toil, their fortunes rise. The meaning of the title (which refers to Japanese pinball gambling, a hugely popular activity there) isn’t obvious in the beginning but becomes clear in the novel’s later sections.

Pachinko tells a universal immigrant story, but it also offers enough specificity to provide a full picture of the geography and customs of 20th-century Korea and Japan. The novel’s scope lets readers see how the family acclimatizes themselves to an increasingly modernized Japan while keeping their own identity as Koreans. Because of the discrimination they face, it’s impossible for them to fully assimilate.

Two more elements of note. Writing instructors and readers often decry the use of “head hopping,” that is, the switching of viewpoints within a scene. Lee shows why this so-called rule was made to be broken. She uses this technique on occasion, but it’s performed subtly and has the effect of enhancing the scene’s emotional impact. Also, while Sunja often hears the adage that suffering is a woman’s plight, she and her equally industrious sister-in-law, Kyunghee, are the engines that ensure their family thrives and survives. The family’s men, while (mostly) decent and hardworking, aren’t always as fortunate. This emphasis felt curious to me; I couldn’t tell if it was meant to be symbolic of a larger theme or not.

If you don’t know anything about this historical era or part of the world, no need to worry. Lee will bring you into her characters’ world so completely so that they’ll feel like family. An engrossing historical saga, Pachinko’s themes are also significantly relevant to the world we live in today.

Pachinko will be published next week by Grand Central in hardcover and ebook ($27 or $13.99, 496pp). Thanks to the publisher for approving my NetGalley access.

It’s a big story, rich in character and activity. These aspects, plus the clean, straightforward writing style, make for a brisk, absorbing read. It opens in 1910 with the circumstances that lead to the birth of the principal heroine, Sunja, who grows into a sturdily built, handsome young woman.

When a liaison with a wealthy fish broker leaves her pregnant, and Sunja learns he can’t marry her, one of the guests recuperating at her mother’s boardinghouse makes a surprising offer. Due to his frailty, Baek Isak never expected to wed anyone, but his Christian beliefs (he’s a Presbyterian minister from Pyongyang) and generosity of spirit leads him to ask for Sunja’s hand. When the couple relocates to Osaka and moves into Isak’s brother’s home in the Korean ghetto, Sunja views firsthand the plight of immigrants living in a country that doesn’t welcome them.

When a liaison with a wealthy fish broker leaves her pregnant, and Sunja learns he can’t marry her, one of the guests recuperating at her mother’s boardinghouse makes a surprising offer. Due to his frailty, Baek Isak never expected to wed anyone, but his Christian beliefs (he’s a Presbyterian minister from Pyongyang) and generosity of spirit leads him to ask for Sunja’s hand. When the couple relocates to Osaka and moves into Isak’s brother’s home in the Korean ghetto, Sunja views firsthand the plight of immigrants living in a country that doesn’t welcome them. The novel was revelatory for me, as it introduced me to an aspect of history about which I’d known little. Between 1910 and 1945, Korea was a colony of Japan. Through the experiences of Sunja, her husband, in-laws, and descendants, we get to see the ramifications of this part of history. As one Korean man remarks in the novel, “For people like us, home doesn’t exist.” In Japan, Koreans are negatively stereotyped as belonging to a “cunning and wily tribe” and “natural troublemakers.” They can’t rent decent housing or obtain the best jobs. On the other hand, any Koreans who adapt to Japanese ways would be looked upon suspiciously back home. The members of the Baek family must always be on their best behavior, since they represent their country of origin.

Over the years, through constant toil, their fortunes rise. The meaning of the title (which refers to Japanese pinball gambling, a hugely popular activity there) isn’t obvious in the beginning but becomes clear in the novel’s later sections.

Pachinko tells a universal immigrant story, but it also offers enough specificity to provide a full picture of the geography and customs of 20th-century Korea and Japan. The novel’s scope lets readers see how the family acclimatizes themselves to an increasingly modernized Japan while keeping their own identity as Koreans. Because of the discrimination they face, it’s impossible for them to fully assimilate.

Two more elements of note. Writing instructors and readers often decry the use of “head hopping,” that is, the switching of viewpoints within a scene. Lee shows why this so-called rule was made to be broken. She uses this technique on occasion, but it’s performed subtly and has the effect of enhancing the scene’s emotional impact. Also, while Sunja often hears the adage that suffering is a woman’s plight, she and her equally industrious sister-in-law, Kyunghee, are the engines that ensure their family thrives and survives. The family’s men, while (mostly) decent and hardworking, aren’t always as fortunate. This emphasis felt curious to me; I couldn’t tell if it was meant to be symbolic of a larger theme or not.

If you don’t know anything about this historical era or part of the world, no need to worry. Lee will bring you into her characters’ world so completely so that they’ll feel like family. An engrossing historical saga, Pachinko’s themes are also significantly relevant to the world we live in today.

Pachinko will be published next week by Grand Central in hardcover and ebook ($27 or $13.99, 496pp). Thanks to the publisher for approving my NetGalley access.

Published on January 31, 2017 05:30

January 26, 2017

Ellen Umansky's The Fortunate Ones, a moving multi-period novel about art, loss, survival, and family

The Kindertransport, the recovery of Nazi-looted art, family ties, and adjustments to great loss: taken individually, these are recurrent themes in literary fiction, but they’re brought together in an original and tremendously moving way in Umansky’s debut novel.

The Kindertransport, the recovery of Nazi-looted art, family ties, and adjustments to great loss: taken individually, these are recurrent themes in literary fiction, but they’re brought together in an original and tremendously moving way in Umansky’s debut novel.It centers on the separate stories of two women, Rose Zimmer and Lizzie Goldstein, and their connection. Both feel like walking ghosts after their parents’ deaths: Rose, a former child refugee from Vienna living in 1940s Britain; and Lizzie, a lawyer who returns home to contemporary Los Angeles for her father’s funeral.

Lizzie and Rose, now an astute, prickly septuagenarian, develop an unusual friendship. Their families had once owned the same Chaim Soutine expressionist painting, and both had it stolen under traumatic circumstances.

The missing artwork holds great meaning for them, and they ponder its whereabouts, but this multi-layered novel isn’t really a mystery – although it satisfies in that respect. Instead, it’s a gradual revelation of character, and of significant events from the women’s personal histories.

Their journeys are engrossing to follow. Rose’s story is brought forward in time from 1936, illustrating her inner strength, while Lizzie navigates relationships with her sister, her Jewishness, and a surprising new lover. The clarity of detail in Umansky’s writing brings all her scenes alive. She sensitively addresses the complicated issue of survivor’s guilt and leaves readers with a sense of hope.

Some notes:

I wrote this (starred) review for Booklist, and the edited version was published in the magazine's January issue. The Fortunate Ones will be published by William Morrow in February in hardcover.

As a sidenote, I found the book's cover art very plain, but what's inside is impressive. I hadn't been familiar with Chaim Soutine or his works before reading the novel; you can read more about him at the Musée de l'Orangerie. The painting connecting Rose and Lizzie's families (The Bellhop) is fictional, but I pictured it along the same lines of this Soutine painting, called The Groom or The Bellboy.

Published on January 26, 2017 15:00

January 22, 2017

Historical fiction award winners from ALA Midwinter 2017

Earlier this evening, a number of literary awards were announced at ALA Midwinter in Atlanta. I wasn't in attendance this time, but details on the winners and shortlisted titles are posted at the ALA website (and committee members have been announcing the news on Facebook and Twitter).

Here are the historical novels that received the honors. Links go to the ALA press releases.

2017 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Fiction: The Underground Railroad, by Colson Whitehead, which imagines an enslaved woman's flight towards freedom. I reviewed this novel here last year.; it also won the 2016 Goodreads Choice Award for historical fiction.

2017 Reading List, which selects the best in genre fiction for adult readers (descriptions are mine):

In the Historical Fiction category, the winner was Graham Moore's The Last Days of Night, a historical thriller about the rivalry between George Westinghouse and Thomas Edison in 1888.

In the Historical Fiction category, the winner was Graham Moore's The Last Days of Night, a historical thriller about the rivalry between George Westinghouse and Thomas Edison in 1888.

On the Historical Fiction short list:

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, a family saga set in Ghana and America over the last few centuries

News of the World by Paulette Jiles, a western set in the post-Civil War period

The Risen: A Novel of Spartacus by David Anthony Durham, about the slave revolt led by Spartacus against ancient Rome

To the Bright Edge of the World by Eowyn Ivey, a novel of adventure and love set in 1885, during the exploration of Alaska.

In the Mystery category, the winner was Thomas Mullen's Darktown, a police procedural featuring two African-American policemen in 1948 Atlanta fighting racism as they investigate a black woman's murder.

And in the Romance category, the winner was Beverly Jenkins' Forbidden, a love story set in the post-Civil War West between a strong-minded African-American woman and a man passing as White.

On the 2017 ALA Notable Books list are several historical novels:

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

To the Bright Edge of the World by Eowyn Ivey

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

An Unrestored Woman by Shobha Rao, stories set during the partition of India in 1947

Novels on the Notable Books list are literary fiction, while the Reading List covers genre fiction. Since novels in the historical fiction genre can also be literary, there is some overlap.

More award announcements may be forthcoming, and if so, I'll add them to this post. Congratulations to the winners and shortlisted authors!

Here are the historical novels that received the honors. Links go to the ALA press releases.

2017 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Fiction: The Underground Railroad, by Colson Whitehead, which imagines an enslaved woman's flight towards freedom. I reviewed this novel here last year.; it also won the 2016 Goodreads Choice Award for historical fiction.

2017 Reading List, which selects the best in genre fiction for adult readers (descriptions are mine):

In the Historical Fiction category, the winner was Graham Moore's The Last Days of Night, a historical thriller about the rivalry between George Westinghouse and Thomas Edison in 1888.

In the Historical Fiction category, the winner was Graham Moore's The Last Days of Night, a historical thriller about the rivalry between George Westinghouse and Thomas Edison in 1888.On the Historical Fiction short list:

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, a family saga set in Ghana and America over the last few centuries

News of the World by Paulette Jiles, a western set in the post-Civil War period

The Risen: A Novel of Spartacus by David Anthony Durham, about the slave revolt led by Spartacus against ancient Rome

To the Bright Edge of the World by Eowyn Ivey, a novel of adventure and love set in 1885, during the exploration of Alaska.

In the Mystery category, the winner was Thomas Mullen's Darktown, a police procedural featuring two African-American policemen in 1948 Atlanta fighting racism as they investigate a black woman's murder.

And in the Romance category, the winner was Beverly Jenkins' Forbidden, a love story set in the post-Civil War West between a strong-minded African-American woman and a man passing as White.

On the 2017 ALA Notable Books list are several historical novels:

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

To the Bright Edge of the World by Eowyn Ivey

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

An Unrestored Woman by Shobha Rao, stories set during the partition of India in 1947

Novels on the Notable Books list are literary fiction, while the Reading List covers genre fiction. Since novels in the historical fiction genre can also be literary, there is some overlap.

More award announcements may be forthcoming, and if so, I'll add them to this post. Congratulations to the winners and shortlisted authors!

Published on January 22, 2017 18:13

January 17, 2017

Some new historical novels retelling the myths of ancient Greece

The heroic and tragic stories from Greek mythology have often been the foundations for historical novels set in long-ago times. Novelists such as Mary Renault, Robert Graves, Margaret George, Colleen McCullough, and Madeline Miller, to name a few, have retold Greek myths in their own styles. They have humanized characters from the ancient tales, showed them from new perspectives, and placed them in a well-researched Bronze Age setting. After being sent a copy of Bright Air Black for review last month, I looked around and noticed many historical novels of this type had been published recently or will be soon. While this may not be significant enough to call it a trend, it's definitely good news for readers who appreciate historical fiction set in the very distant past.

Here are nine books from 2016 and 2017 that fit this category. Please note that this list includes both US and UK releases. If you know of others that belong, please leave a comment.

This retelling of Helen of Troy has Helen separated from Theseus, the man she loves, and taking her fate into her own hands; it's the sequel to the author's earlier Helen of Sparta. Lake Union, May 2016.

This Bronze Age-set historical fantasy, set two decades before the author's Helen novels, retells a lesser-known myth: that of Hippodamia, who is raised by centaurs, and her husband Pirithous, future king of the Lapiths. CreateSpace, Sept. 2016.

Set in Bronze Age Greece, and subtitled "a novel of Homer's Odyssey," Dillon's version recounts the events from the epic poem from the viewpoint of Odysseus's son, Telemachus. Pegasus, August 2016.

Hauser's debut novel, first published in the UK last year, retells the Trojan War story from the viewpoints of two women: Briseis and Krisayis. Pegasus, January 2017.

Hauser's second novel, out in the UK later this year. will be a retelling of the myth of Atalanta, who survived being abandoned as an infant and grew into a swift runner and warrior. Doubleday UK, June 2017.

Oedipus and Antigone are the best-known figures from Sophocles' two tragedies. Haynes' novel retells these stories from the viewpoints of Jocasta and Ismene, the mother and daughter whose destinies play out in the ancient kingdom of Thebes. Mantle (UK), May 2017.

Like the previous projects from the "H Team" (which include A Day of Fire , about Pompeii, and A Year of Ravens, about Boudica's rebellion), A Song of War is a collaborative novel in which multiple authors contribute different characters' perspectives on a historical event of significance. Here, seven historical novelists retell the epic of the Trojan War. CreateSpace, October 2016.

This novel promises to be a sympathetic retelling of the story of Clytemnestra, a notorious woman in Greek mythology for taking deadly revenge on her husband, Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, after the Trojan War. Scribner, May 2017.

A retelling of the story of Medea, Jason, and the voyage of the Argonauts. I'll be posting a full review later on. The cover shows, as seen from above, a ship skimming through dark waters. Black Cat, March 2017.

Here are nine books from 2016 and 2017 that fit this category. Please note that this list includes both US and UK releases. If you know of others that belong, please leave a comment.

This retelling of Helen of Troy has Helen separated from Theseus, the man she loves, and taking her fate into her own hands; it's the sequel to the author's earlier Helen of Sparta. Lake Union, May 2016.

This Bronze Age-set historical fantasy, set two decades before the author's Helen novels, retells a lesser-known myth: that of Hippodamia, who is raised by centaurs, and her husband Pirithous, future king of the Lapiths. CreateSpace, Sept. 2016.

Set in Bronze Age Greece, and subtitled "a novel of Homer's Odyssey," Dillon's version recounts the events from the epic poem from the viewpoint of Odysseus's son, Telemachus. Pegasus, August 2016.

Hauser's debut novel, first published in the UK last year, retells the Trojan War story from the viewpoints of two women: Briseis and Krisayis. Pegasus, January 2017.

Hauser's second novel, out in the UK later this year. will be a retelling of the myth of Atalanta, who survived being abandoned as an infant and grew into a swift runner and warrior. Doubleday UK, June 2017.

Oedipus and Antigone are the best-known figures from Sophocles' two tragedies. Haynes' novel retells these stories from the viewpoints of Jocasta and Ismene, the mother and daughter whose destinies play out in the ancient kingdom of Thebes. Mantle (UK), May 2017.

Like the previous projects from the "H Team" (which include A Day of Fire , about Pompeii, and A Year of Ravens, about Boudica's rebellion), A Song of War is a collaborative novel in which multiple authors contribute different characters' perspectives on a historical event of significance. Here, seven historical novelists retell the epic of the Trojan War. CreateSpace, October 2016.

This novel promises to be a sympathetic retelling of the story of Clytemnestra, a notorious woman in Greek mythology for taking deadly revenge on her husband, Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, after the Trojan War. Scribner, May 2017.

A retelling of the story of Medea, Jason, and the voyage of the Argonauts. I'll be posting a full review later on. The cover shows, as seen from above, a ship skimming through dark waters. Black Cat, March 2017.

Published on January 17, 2017 16:00