Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 15

September 8, 2023

Interview with Trish MacEnulty, author of Cinnamon Girl, a 15-year-old girl's picaresque journey through the tumultuous early '70s

Trish MacEnulty's Cinnamon Girl takes its heroine, 15-year-old Eli Burnes, on a wild, wide-ranging ride through the social and political atmosphere of her era. The story opens in Augusta, Georgia in 1970. After her step-grandmother Mattie dies, Eli hops a ride north with her best friend's brother, who's running away from the Vietnam War draft. Her adventures continue from there. Eli's father Billy, a DJ in St. Louis, had remarried and has another family but eventually re-enters the picture; he comes to serve as a role model in ways Eli doesn't expect. The book is a fantastic read: fast-moving, full of smoothly woven historical detail and rich characterizations, all told in Eli's appealing voice. I know Trish through the Historical Novel Society and was glad for the opportunity to speak with her about her latest release, which is out today from Livingston Press of the Univ. of West Alabama.

Trish MacEnulty's Cinnamon Girl takes its heroine, 15-year-old Eli Burnes, on a wild, wide-ranging ride through the social and political atmosphere of her era. The story opens in Augusta, Georgia in 1970. After her step-grandmother Mattie dies, Eli hops a ride north with her best friend's brother, who's running away from the Vietnam War draft. Her adventures continue from there. Eli's father Billy, a DJ in St. Louis, had remarried and has another family but eventually re-enters the picture; he comes to serve as a role model in ways Eli doesn't expect. The book is a fantastic read: fast-moving, full of smoothly woven historical detail and rich characterizations, all told in Eli's appealing voice. I know Trish through the Historical Novel Society and was glad for the opportunity to speak with her about her latest release, which is out today from Livingston Press of the Univ. of West Alabama.You’ve written other works of historical fiction, but did you find the process any different for this one, since the era is more recent? Did your own memories from having lived through the early ‘70s help as far as researching the historical backdrop to Cinnamon Girl?

Also, you’d mentioned in an interview with the HNS that Cinnamon Girl is a rewritten version of an earlier novel of yours. What did the rewriting process involve, as far as what you felt needed updating?

I've combined your two questions. I wrote a version of this book at least ten years before I wrote my historical fiction. And so it was a very different process. Much of Eli's life is rooted in my own experiences—first love, running away from home, going to rock festivals and concerts, hanging out in headshops.

In my earlier version of the book, I didn't set the historical context as well as I could have. But after writing several historical mysteries and learning how important history is to the narrative, I went back and did the research—searching out news stories about the Weathermen, Vietnam, and racial oppression. I also learned a lot about the advent of FM radio! I actually looked up the set lists and venues for various rock concerts that are in the book. And yes, having lived through the era definitely informed my choices as to which historical events to include. For example, I remembered the Kent State killings, which became an important event in the background of Eli's story. The killing of those four students by the National Guard was so emblematic of what the counterculture faced at the time.

Eli’s narrative voice is really appealing. She’s adventurous and spirited but still naïve in some ways, and she has an infectious sense of humor. How did her voice come to you?

I used to teach creative writing at a summer arts camp in Rock Hill, South Carolina. And each year as I wrote the book, I would read chapters to the kids. I think being surrounded by teenagers and raising one while I was writing the book helped me get in the right mindset. Eli also embodies a lot of my own naiveté from that age. It was a more innocent era, for sure.

I do like to include a thread of humor in all of my writing.

You’ve included a quote from Jack Kerouac’s On the Road to introduce the novel, and the book itself makes some appearances—plus, Eli spends a good amount of time on the road herself in early '70s America. How have Kerouac and his novel influenced your work?

(At first I had a quote from Neil Young's song "Cinnamon Girl" as an epigraph but then I found out how much the rights would cost so I changed it.) But yes, Kerouac was the perfect choice because On the Road is almost quintessentially picaresque—a sort of plotless, episodic story of the adventures of ne'er-do-wells. I think of this book as a picaresque as well.

I'll never forget when I first read On the Road. I was in college, and my life wasn't exactly going smoothly. I was living the darker side of the 1970s by then. My future didn't look all bright and shiny. I had this vague idea of being a writer, and then reading that book ignited the internal catalyst. I knew that I had to be a writer after that. It didn't matter if my life wasn't pretty and perfect because someday I'd write my stories. I just had to survive long enough to get there.

So when Eli is on the road herself, of course someone comes along and gives her a copy. In a way, it will be her talisman.

Eli gets a front-and-center view of many important cultural moments during a key year in her life. What were some of the most memorable parts of the research process along these lines?

The most memorable part of the research was when I learned about the riots in Augusta that occurred in 1970. I actually grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, and I remember several riots. I never witnessed a killing but I heard about them and I knew they happened. I set Eli's early story in Augusta because I wanted that smaller city feel and because it has a river. (Rivers seem to show up in everything I write.) It was only after I had chosen that locale, that I learned about the riot, in which six Black men were gunned down by law enforcement. I knew that event would have to inform the rest of the book. It would make an impression.

Some research came about by happenstance. Several years ago I got the chance to interview a woman who had been in the Weather Underground, and her experiences helped me understand — and sympathize with—their motivations. That led me to read about the Days of Rage and other actions during the anti-war protests. Another episode I learned about years ago was the murder of Freddy Hampton in Chicago, again by law enforcement, while his pregnant wife lay in bed next to him. The killing of that brilliant young leader haunts me.

I loved the character of Billy, who’s an atypical father figure in many ways, but he and Eli come to develop a natural rapport. Is he based on anyone? How did you develop his character?

Billy is very loosely based on my older brother, who was a symphony musician in St. Louis, Missouri. I lived with him and his wife and two kids (a boy and a girl) for a year. He was adamantly opposed to the war in Vietnam, and his wife was a proponent of La Leche League, an organization that promotes breastfeeding. He wasn't involved with the Weatherman organization, but he did attend protests and worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee (SNCC). Some of my other brother's experiences are also part of Billy's past. I didn't have a good relationship with my own father, so both of my brothers fulfilled that role in my life.

If Cinnamon Girl had an accompanying soundtrack, which songs would be on it?

This answer almost writes itself. Of course, Neil Young's "Cinnamon Girl," and Moody Blues' "Nights in White Satin," Elton John's "Your Song" as well as the Dead and the Allman Brothers, and B.B. King. When I was that age, most of the concerts we attended were those in which the band members were all young guys, and it's too bad that I don't have any concerts with women performers in the book. But Grace Slick's "White Rabbit" would have to be one of the major songs on the soundtrack and also Janis Joplin's "Me and Bobby McGee." Now, there would also have to be some opera. Definitely Mimi. Maybe something from Carmen as well.

Thanks very much, Trish!

Visit Trish MacEnulty's website for more information on all of her books, which include standalone novels, short stories, a memoir, and a four-book historical mystery series set in early 20th-century Manhattan.

Published on September 08, 2023 05:00

September 5, 2023

Interview with Kathleen B. Jones, author of Cities of Women, her multi-period debut about women's creativity and medieval art

In this first of two interviews this week, I'm speaking with Kathleen B. Jones about her debut novel, Cities of Women, which interweaves two stories, centuries apart. In 2018, history professor Verity Frazier shifts the course of her research to focus on the manuscripts of 14th/15th-century writer Christine de Pizan, with the goal of proving that the beautiful illuminations accompanying the text were painted by a woman named Anastasia.

In this first of two interviews this week, I'm speaking with Kathleen B. Jones about her debut novel, Cities of Women, which interweaves two stories, centuries apart. In 2018, history professor Verity Frazier shifts the course of her research to focus on the manuscripts of 14th/15th-century writer Christine de Pizan, with the goal of proving that the beautiful illuminations accompanying the text were painted by a woman named Anastasia. Alongside Verity's pursuit, the long-forgotten life story and career of a medieval artist named Béatrice (later called Anastasia) are revealed. The novel is itself vividly detailed, with reflections on women's determined pursuits throughout the ages and a well-researched atmosphere of medieval France. And as a researcher myself, I enjoyed following where Verity's discoveries led her, both academically and emotionally, as she begins a new relationship with a woman whose scholarly interests in the Middle Ages intersect with hers. Thanks to Kathy for her responses to my questions! Cities of Women is published today by Keylight Books/Turner Publishing.

What inspired you to begin writing historical fiction? Had it been an interest of yours during your academic career, or did the subject pique your attention afterward?

Academic historians often begin their academic essays and books with a story. That style of writing has been less prominent in my academic field—political theory. During the decades I taught about women’s political movements, I learned students connected with the past much more and saw its relevance to the present when I brought historical conflicts into focus through narratives, stories filled with flawed though relatable characters struggling against the odds to achieve personal and political change. I began to experiment with a different kind of writing in my own academic publications and finally moved into creative nonfiction and then fiction to be able to fully express the complexity of what I wanted to say about the human condition.

I’ve always been a reader of fiction and gravitated toward writing historical fiction because it satisfied two loves of mine at once—doing deep research and letting one’s imagination visit and try to understand unfamiliar times, people and places. In this regard, the political theorist Hannah Arendt has been a major influence in all my writing. Storytelling was a key element in her work.

So, for me, there’s been a kind of parallel trajectory between the progression of my academic writing and the urgency I’ve felt to write fiction set in the past that still resonates with the present.

I hadn’t been familiar with Anastasia, the historical manuscript illuminator about whom little is known, and appreciated the narrative you created for her. She seems to have been very well known in artistic circles in her time. How did you get into the mindset of a female artist from medieval times?

I’m excited you found the medieval Anastasia both a convincing and intriguing character because we don’t really know whether she actually existed or was merely someone Christine de Pizan invented to call attention to the work of female artists in the Middle Ages.

With no more of a clue than a name found in Christine’s Book of the City of Ladies, I invented the character of Béatrice/Anastasia and the entirety of her storyline. Since Christine had written City of Ladies as a defense of women’s worldly contributions and was known to oversee very closely the production of her books, I speculated she would have chosen a woman artist to illuminate images of her imagined city. Research into the medieval Parisian book trade identified the existence of women artists of the book, giving me a factual basis for my speculation, though only in the most general sense. I gave this speculation to Verity, in the modern timeline, to drive forward her quest to document Anastasia’s role in Christine’s work.

Kouky Fianu, a Canadian historian who researched medieval book production in Paris, pointed me in the direction of a GIS map of medieval Paris available online that located the ateliers of various artists, including women who illuminated manuscripts. That visual, combined with all the books and articles I read about medieval women’s lives, helped me imagine what it might have been like for a young woman in fourteenth-century France who’d been exposed to art as a girl and then had experienced her family’s life and livelihood being decimated by the plague, become driven to become an artist. Her determination to create something luminous in the face of looming disaster drives her to overcome all odds and make it to Paris.

How did you decide on the parallel narrative structure for the book, with both medieval and contemporary timelines?

I wanted to generate a plot illuminating linkages between past and present. As Faulkner once wrote in Requiem for a Nun, “the past is never dead; it’s not even past.”

On the deepest level, I wanted the novel to explore the human experience of time, how we mortals live in a world that persists beyond our life span. But, because we can produce things—stories, both written and oral, works of art, etc.—we leave behind traces of who we were and what we did. Remembrance gives us a kind of immortality.

Verity’s effort to document Anastasia’s work as an artist memorializes her. Her quest transforms Verity in the present as much as it dignifies Anastasia’s life in the past.

Related to the human experience of time is how we understand history, whether on a grand scale or at the level of an individual life. In my novel, historical events, both personal and political, appear to drive the plot of Christine’s story. Yet, Verity’s quest intersects the story of Anastasia, a fictional character, with the story of Christine, a factual character, and changes what we think we know about the past. If there was an artist named Anastasia with whom Christine worked on her manuscripts, how does that relationship affect each woman’s life, how we make sense of their lives, and how we understand the broader history in which these women lived?

I especially enjoyed the descriptions of the illuminated manuscripts and the process by which they were created. In the acknowledgments, you credit the assistance of librarians in the British Library’s manuscript reading room, and in the novel, Verity strives to see the manuscripts of Christine de Pizan’s work in person. Were you able to view any original manuscripts, and if so, what did you take away from the experience?

I wasn’t able to view “in person” Harley 4431, the collection of Christine’s writings known as The Queen’s Book that features so prominently in the novel. The entire manuscript is available online. Like Verity, I spent hours and hours staring at its folios. But I was able to touch several other copies of Christine’s books, which are held in the Manuscript Reading Room of the British library. I also attended a workshop on manuscript making at the Morgan Library in New York, similar to the one in the novel that Verity takes part in. In that workshop, I learned about parchment making, about medieval inks, and the work of scribes and illuminators. I also got to touch several rare manuscripts held in the Morgan’s collection, which were on display during the workshop. That tactile experience deeply affected my writing about the creation of those amazing illuminated manuscripts. I actually wrote an essay about this for LitHub.

What were some of the most memorable parts of the research or writing process for you?

Besides wandering the streets of medieval Paris via the GPS maps I mentioned earlier, some of the most memorable parts of the research never made it into the novel! I cut three chapters I’d written about fourteenth-century Venice, where Christine was born when he father worked as advisor to the Doge. In the course of researching that period of Venetian history, I came across information about prostitution in Venice that surprised me: because there had been so much corruption when men ran the brothels, the leaders of the city changed the law and put women in charge of the trade.

I might go back to that research and resurrect those characters and their stories for another novel. For the moment, though, I’m halfway through my second novel, stimulated by what I learned about another medieval manuscript, a Book of Hours the Nazis stole during World War II from the collection of the Parisian Rothschilds. The book was later recovered under mysterious circumstances and donated to the Bibliotheque Nationale.

As for the writing process, most memorable was becoming so deeply immersed in the story that by the time I finished writing I wasn’t exactly sure any more where the boundary was between what I had invented and what was historical fact.

One remark made by Béatrice/Anastasia in the novel, in relation to her paintings, struck me as especially poignant with regard to writing as well: “How far would my imagination be allowed to stretch composition to reveal things not yet known about women’s lives?” How do you see the role of historical fiction as it relates to the hidden history of women?

That’s such a great question, Sarah! Archives and artifacts can tell us a lot about women’s lives that traditional history has kept hidden or distorted. Tiya Miles’s All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake, is a remarkable example of the hidden history that one artifact can reveal. Miles writes how that sack, now displayed in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, “filters a light of remembrance on the viewer’s own familial bonds, leading any one of us to ask what things our own families possess that connect us to our past and wonder what we might gain from contemplation of that connection.”

I think fiction set in the past filters a similar “light of remembrance” but amplified by the powers of imagination. Fiction can take the reader on a more embodied and emotionally resonant journey into the history of yet unknown or lesser-documented experiences. Nonfiction tells us about the past; fiction—at least the kind I’m writing— invites us to experience the textures, smells, tastes, sounds of the past more viscerally by empathizing with characters’ conflicts, whether those characters, likeable or not, are human or non-human or even inanimate objects or historical events in women’s history.

~

Born and educated in New York City, Kathleen B. Jones taught feminist theory for twenty-four years at San Diego State University. In addition to many scholarly books, she penned two memoirs: Living Between Danger and Love (Rutgers University Press, 2000) and the award-winning Diving for Pearls: A Thinking Journey with Hannah Arendt (Thinking Women Books, 2015). Her essays and short fiction have appeared in Fiction International, Humanities Magazine, and The Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. Among numerous awards, she received multiple grants from the National Endowment of the Humanities, writers’ grants to the Vermont Studio Center, an honorary doctorate from Örebro University, Sweden, and a distinguished alumni award from CUNY Graduate Center. She lives in Stonington, Connecticut. Visit her website at https://www.kbjoneswrites.com.

Published on September 05, 2023 04:30

August 31, 2023

Man of Sorrows by M.N. Stroh details an unusual romance from early medieval Ireland

This first in a four-part series takes place in a scrupulously researched mid-10th century Ireland amid warring clans and Danish invaders. Subtitled “a medieval Christian romance,” Man of Sorrows centers several families and two different love stories, each of which is daring for its time and for the genre.

This first in a four-part series takes place in a scrupulously researched mid-10th century Ireland amid warring clans and Danish invaders. Subtitled “a medieval Christian romance,” Man of Sorrows centers several families and two different love stories, each of which is daring for its time and for the genre.Mara, a fifteen-year-old shepherdess, receives divine visitations that predict the future (like her late mother’s demise) and direct her to marry a man who will “humble himself by the sign of the cross.” After she sees a sign that her proposed husband is her best friend Áine’s brother, Marcan, she knows she’ll have trouble convincing him: Marcan is a pious monk at the Cill Dálua community who transforms vellum into beautiful, illuminated manuscripts.

Because he thinks he unwittingly caused his mother’s and brother’s deaths, Marcan accepts the abbot’s harsh rule. His father, needing Marcan to tend flocks at home, had waited to give him to the church, as he was duty-bound to do with his firstborn, and Marcan feels God is punishing him for the delay. The second romance involves the cross-class relationship between Áine and Davan, nephew of Chief Cennedigh of the Dal Cais, in a subplot that offers multiple surprises.

In this short novel, Stroh proficiently interweaves multiple viewpoints and plot threads without losing the reader’s attention. The characters and their religious beliefs feel period-appropriate. Mara’s steadfastness is admirable, and Marcan’s internal pain is evident as he struggles to determine God’s purpose for his life. The writing style ranges from smooth to overly formal and cumbersome (“I exist but to guard his means so that he might dote upon you”). The novel also needs a stronger copyedit. With the trials they undergo, Mara and Marcan deserve a happy ending, and it’s rewarding to see how they achieve it.

Man of Sorrows was published by Olivia Kimbrell Press in 2022; I wrote this review for the Historical Novels Review's August 2023 issue. The next three books in the series, which feature different characters from this book and are set two decades later, in the 960s, are Rise of Betrayal, Lord of Vengeance, and Stone of Division. Cill Dálua is now known as Killaloe, a town and parish in County Clare.

Published on August 31, 2023 15:37

August 26, 2023

The Island of Doves sweeps readers away to historic Mackinac Island

My father’s family are Michiganders, going back to the state’s rustic pioneer days in the mid-19th century. When I was growing up, we spent many summer weeks visiting my grandmother and other relatives, and some of these excursions involved trips to Mackinac (pronounced “Mackinaw”) Island, a picturesque isle sitting in the middle of Lake Huron, between Michigan’s Lower and Upper Peninsulas. The romantic time-travel film Somewhere in Time, set in 1912 and decades later, took place there.

My father’s family are Michiganders, going back to the state’s rustic pioneer days in the mid-19th century. When I was growing up, we spent many summer weeks visiting my grandmother and other relatives, and some of these excursions involved trips to Mackinac (pronounced “Mackinaw”) Island, a picturesque isle sitting in the middle of Lake Huron, between Michigan’s Lower and Upper Peninsulas. The romantic time-travel film Somewhere in Time, set in 1912 and decades later, took place there.Kelly O’Connor McNees’ The Island of Doves is also set on Mackinac, quite a bit earlier – in the 1830s, when the small piece of land was loosely populated by Odawa Indians, French settlers and traders, Métis families who were the descendants of both, and white Presbyterians relocating to Michigan from the east. One of its main attractions are the beautiful images of Mackinac’s unspoiled wilderness and waterscapes, and the depictions of life on the frontier: tending gardens, producing maple syrup, sewing moccasins, traveling by sled dog and canoe.

McNees’ two heroines are easy to warm to. As the wife of one of Buffalo’s leading business moguls, Susannah Fraser has no material wants. Her husband Edward is physically and emotionally abusive, though, and Susannah, being a proud woman, tries to endure the pain on her own, preferring to spend her days tending plants in her greenhouse. Magdelaine Fonteneau, an adventurous widow in her forties of part-Odawa, part-French heritage, lives permanently on Mackinac but has amassed a small fortune as a fur trader. Having lost both her younger and older sisters decades earlier – in particular, young Josette had been killed by a jealous suitor – she opens her home to Susannah when she needs a safe haven. Susannah’s maid and a kindly nun in Buffalo arrange for her escape via steamboat. The trials on the voyage force Susannah (who now uses the last name Dove) to confront life’s unsavory side but also go far in teaching her self-sufficiency.

The plot centers on relationships and character growth, as Susannah gains independence and Magdelaine learns to accept that her adult son, Jean-Henri, has a calmer personality than that of his ambitious, risk-taking late father. The story dwells more on religious differences, particularly those between Protestants and Catholics, than race relations at the time. I had hoped for something deeper in that respect. The story is rewarding, though, with the writing as smooth and clear as the pristine waters near Magdelaine’s home. It’s a pleasant journey into a little-known aspect of America’s past. The author’s notes reveal that Magdelaine is closely based on a historical figure, and her story is also worth knowing.

The Island of Doves was published by Berkley in 2014. I read this book (from my own collection) at the start of the pandemic, wrote a review, then got distracted and forgot I hadn’t posted it! So I thought I would do so now.

Published on August 26, 2023 12:00

August 19, 2023

Alys Clare's mystery The Cargo from Neira leads its physician protagonist into the 17th-century spice trade

The bustling, cutthroat spice trade forms the enticing backdrop for the fifth volume in Clare’s mystery series featuring country doctor Gabriel Taverner in early 17th-century Devon. If you haven’t read the previous four books, no need to worry, since it stands alone well. Banda Neira, the place of the title, is a remote Indonesian island that was the world’s main source for nutmeg, a spice in high demand in Europe for its food preservation and reputed medicinal properties.

The bustling, cutthroat spice trade forms the enticing backdrop for the fifth volume in Clare’s mystery series featuring country doctor Gabriel Taverner in early 17th-century Devon. If you haven’t read the previous four books, no need to worry, since it stands alone well. Banda Neira, the place of the title, is a remote Indonesian island that was the world’s main source for nutmeg, a spice in high demand in Europe for its food preservation and reputed medicinal properties.In February 1605, Gabriel gets drawn into a mystery when the coroner’s manservant fetches him to view a body on the banks of the river Tavy, with the hopes he’ll conceal it was a suicide since these victims would be damned for eternity and their family penalized. The poor soul is a woman, single and six months pregnant, which could explain her desperate circumstances.

To Gabriel’s shock, the woman soon revives. Gabriel tends to her at Rosewyke, his home, but she’s petrified, unhappy to be alive, and unwilling to talk. Then a second body, a man’s, turns up in a cesspit in a seedy quayside alley of Plymouth with several costly nutmegs in his mouth. Gabriel feels the two incidents must be connected, especially after an attempted break-in at Rosewyke that terrifies his patient and gets him firmly into sleuthing mode.

The principal cast are a congenial bunch whose close-knit relationships contrast nicely with the danger stalking them. Gabriel’s sister, Celia, is a sharp-witted young widow, while housekeeper Sallie prepares comforting meals at a moment’s notice. Most intriguing are the changes within Gabriel as his investigation proceeds. A former ship’s surgeon now living shoreside after an injury, he starts feeling a strong pull to return. While abrupt, the viewpoint switches prove enlightening, and the mystery’s resolution, which offers surprises for Gabriel and the reader, is admirably well-plotted.

The Cargo from Neira was published in May by Severn House, and this review also appears on the Historical Novel Society website. I'm looking forward to reading both the earlier volumes in this series, and later ones as they appear.

Published on August 19, 2023 08:38

August 16, 2023

How I wrote a true story as a novel, a guest post by Julia Park Tracey, author of The Bereaved

Historical fiction and historical nonfiction are interrelated and can be based on the same material. But when an author gets an idea for a new project, how do they decide which route to take? Read about Julia Park Tracey's experience below, and many thanks to the author for her thought-provoking essay!

~

How I Wrote a True Story as a NovelJulia Park Tracey

I first started writing The Bereaved (a novel) as nonfiction. I'm a journalist by trade, and that means I look for facts and figures and actual quotes and information. I had just finished editing the second of two books called The Doris Diaries, about a teenager flapper in the Roaring Twenties. They were my great aunt’s diaries that I had inherited after she died. I had done a ton of background research, everything from teenagers in society, what were they eating and drinking, cars and technology, social upheaval, medical practices, clothes and fashion, and so on. I wrote a long introduction, several appendices, and indexed both books.

I first started writing The Bereaved (a novel) as nonfiction. I'm a journalist by trade, and that means I look for facts and figures and actual quotes and information. I had just finished editing the second of two books called The Doris Diaries, about a teenager flapper in the Roaring Twenties. They were my great aunt’s diaries that I had inherited after she died. I had done a ton of background research, everything from teenagers in society, what were they eating and drinking, cars and technology, social upheaval, medical practices, clothes and fashion, and so on. I wrote a long introduction, several appendices, and indexed both books.

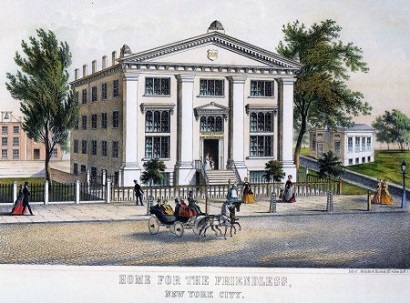

As a journalist and a part-time scholar of women’s history, I fully intended to take the story of The Bereaved—the true story of my third great grandmother and how she lost four of her children to the Orphan Trains, and how she tried to get them back—and tell it as nonfiction. In fact, I was excited at becoming known as a writer of women's history and telling untold stories.

I knew all of the facts of this story. But I wasn't quite sure how I was going to tell it. I laid it out chronologically and looked at the details, and I read several books of creative nonfiction about historical events. I took my outline with me to the Community of Writers at the Olympic Valley in Lake Tahoe and shared it with my group. The other writers gave me a lot of great ideas—for how to write a novel. So did the male leader of my group in my one-on-one meeting.

I was outraged. Are they saying that women should write novels instead of serious history? I spent a lot of time in the next two months raging internally about the misogyny inherent in that idea. But at the same time, I wanted to know what it was like to be Martha Seybolt Lozier.

So I bought some fabric and I bought a pattern for a Civil War dress; I cut it out and started sewing by hand. I sat in that wicker chair by the window and stitched lace and facings and top-stitched. I continued my hand sewing, between bouts of further research into her days and her era, while thinking about Martha and her children.

And as I sewed, I started thinking about all the things that Martha knew.

She knew how a pound of butter felt in the hand. How an old hen’s pulse beat against her fingers before she twisted its neck. How the feathers made a thin wet pop as she pulled them from the cooling skin.

That was the first paragraph that I wrote: Some of the things that Martha would know from living on a farm. And I knew that the language of living on a farm was what informed her character. I kept hearing Martha in my thoughts—what she might think about things and what she might have to do.

Managing the eggs: They need to be wiped but not washed. They’ll keep for weeks, but store them away from onions, fish, the smokehouse.

Ducks rose from the water loud with their honking voices, their clumsy splashing, the rapid beat of wings. How did Canada geese make flight so graceful, while ducks just seemed late and worried and fatigued? Like herself.

I kept writing what I was thinking about. And then when November rolled around and it was time for NaNoWriMo, I took advantage of the thirty days of enforced writing and coughed up a 50,000-word draft. Later, I went back through and wrote it again, adding another 40,000 words. Martha took shape, and so did her children, and so, too, The Bereaved.

Instead of writing in a journalistic style, I was writing a close third person, telling Martha’s story and (gasp) filling in the details that I imagined, that I invented: The color of her hair, her eyes. Her relationship with her in-laws. The terrible thing that made her flee from the farm. And so on—breaking the sacred journalism rule that Everything Must Be True.

I reality, there are many facts I don’t know about Martha. I have not yet seen a photo, if any exist. I found her burial site but not when she died. I have seen her signature but I don’t know her voice or anything she might have said directly. All of my quotes are imagined.

For a journalist like me, that was hard to do—but Martha and her story are worth it.

The Bereaved: A Novel—Historical fiction by Julia Park Tracey; Sibylline Press, August 2023; 270 pages; ISBN 9781736795422. $18.

Julia Park Tracey, a journalist of 40 years, is the author of seven books. Her latest is The Bereaved, historical fiction about a destitute widow who takes her children to an aid society in New York City for safekeeping, but the agency sends them out on the Orphan Train, and the bereaved mother must find her children again (based on the story of her third great grandmother). Find her online, any platform, @juliaparktracey.

~

How I Wrote a True Story as a NovelJulia Park Tracey

I first started writing The Bereaved (a novel) as nonfiction. I'm a journalist by trade, and that means I look for facts and figures and actual quotes and information. I had just finished editing the second of two books called The Doris Diaries, about a teenager flapper in the Roaring Twenties. They were my great aunt’s diaries that I had inherited after she died. I had done a ton of background research, everything from teenagers in society, what were they eating and drinking, cars and technology, social upheaval, medical practices, clothes and fashion, and so on. I wrote a long introduction, several appendices, and indexed both books.

I first started writing The Bereaved (a novel) as nonfiction. I'm a journalist by trade, and that means I look for facts and figures and actual quotes and information. I had just finished editing the second of two books called The Doris Diaries, about a teenager flapper in the Roaring Twenties. They were my great aunt’s diaries that I had inherited after she died. I had done a ton of background research, everything from teenagers in society, what were they eating and drinking, cars and technology, social upheaval, medical practices, clothes and fashion, and so on. I wrote a long introduction, several appendices, and indexed both books. As a journalist and a part-time scholar of women’s history, I fully intended to take the story of The Bereaved—the true story of my third great grandmother and how she lost four of her children to the Orphan Trains, and how she tried to get them back—and tell it as nonfiction. In fact, I was excited at becoming known as a writer of women's history and telling untold stories.

I knew all of the facts of this story. But I wasn't quite sure how I was going to tell it. I laid it out chronologically and looked at the details, and I read several books of creative nonfiction about historical events. I took my outline with me to the Community of Writers at the Olympic Valley in Lake Tahoe and shared it with my group. The other writers gave me a lot of great ideas—for how to write a novel. So did the male leader of my group in my one-on-one meeting.

I was outraged. Are they saying that women should write novels instead of serious history? I spent a lot of time in the next two months raging internally about the misogyny inherent in that idea. But at the same time, I wanted to know what it was like to be Martha Seybolt Lozier.

So I bought some fabric and I bought a pattern for a Civil War dress; I cut it out and started sewing by hand. I sat in that wicker chair by the window and stitched lace and facings and top-stitched. I continued my hand sewing, between bouts of further research into her days and her era, while thinking about Martha and her children.

And as I sewed, I started thinking about all the things that Martha knew.

She knew how a pound of butter felt in the hand. How an old hen’s pulse beat against her fingers before she twisted its neck. How the feathers made a thin wet pop as she pulled them from the cooling skin.

That was the first paragraph that I wrote: Some of the things that Martha would know from living on a farm. And I knew that the language of living on a farm was what informed her character. I kept hearing Martha in my thoughts—what she might think about things and what she might have to do.

Managing the eggs: They need to be wiped but not washed. They’ll keep for weeks, but store them away from onions, fish, the smokehouse.

Ducks rose from the water loud with their honking voices, their clumsy splashing, the rapid beat of wings. How did Canada geese make flight so graceful, while ducks just seemed late and worried and fatigued? Like herself.

I kept writing what I was thinking about. And then when November rolled around and it was time for NaNoWriMo, I took advantage of the thirty days of enforced writing and coughed up a 50,000-word draft. Later, I went back through and wrote it again, adding another 40,000 words. Martha took shape, and so did her children, and so, too, The Bereaved.

Instead of writing in a journalistic style, I was writing a close third person, telling Martha’s story and (gasp) filling in the details that I imagined, that I invented: The color of her hair, her eyes. Her relationship with her in-laws. The terrible thing that made her flee from the farm. And so on—breaking the sacred journalism rule that Everything Must Be True.

I reality, there are many facts I don’t know about Martha. I have not yet seen a photo, if any exist. I found her burial site but not when she died. I have seen her signature but I don’t know her voice or anything she might have said directly. All of my quotes are imagined.

For a journalist like me, that was hard to do—but Martha and her story are worth it.

The Bereaved: A Novel—Historical fiction by Julia Park Tracey; Sibylline Press, August 2023; 270 pages; ISBN 9781736795422. $18.

Julia Park Tracey, a journalist of 40 years, is the author of seven books. Her latest is The Bereaved, historical fiction about a destitute widow who takes her children to an aid society in New York City for safekeeping, but the agency sends them out on the Orphan Train, and the bereaved mother must find her children again (based on the story of her third great grandmother). Find her online, any platform, @juliaparktracey.

Published on August 16, 2023 04:49

August 13, 2023

Mona Susan Power's A Council of Dolls evokes Dakota women's survival across three generations

Power, an enrolled Standing Rock Sioux tribal member, has penned an original saga detailing how forced colonization impacts three generations of Dakhóta women. She writes sensitively from each young protagonist’s viewpoint while also showing how their childhood ordeals affect them and their families over time.

Power, an enrolled Standing Rock Sioux tribal member, has penned an original saga detailing how forced colonization impacts three generations of Dakhóta women. She writes sensitively from each young protagonist’s viewpoint while also showing how their childhood ordeals affect them and their families over time. In the 1960s, Sissy grows up in Chicago with her loving father and troubled mother, Lillian. We then learn Lillian’s history in 1930s North Dakota as she and her sister, Blanche, are sent to an Indian boarding school in Bismarck, where their cruel assimilation into white culture leads to a tragedy Lillian can’t recover from. In the 1900s, Lillian’s mother, Cora, travels to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania and survives the attempted stripping of her heritage.

Each girl has a doll who feels fully alive to her, serving as her confidant and protector. The final account, where an adult Sissy analyzes the dolls’ roles, processes her ancestors’ pain, and reclaims their power is beautifully healing and hopeful. This heart-wrenching account of inherited trauma and resilience is perceptively told.

A Council of Dolls was published by Mariner/HarperCollins on August 8; I wrote this review for Booklist. Not easy to encapsulate four separate stories into a 175-word review! There's much I had to leave out or only hint at. As Susan Power, the author has also written several other novels, including The Grass Dancer (1997), a saga spanning generations that's set on a reservation in North Dakota and likewise reflects her Sioux heritage.

Published on August 13, 2023 05:00

August 8, 2023

Isabel Allende's The Wind Knows My Name draws parallels between stories of child migrants in modern history

In her compassionate novel, Allende draws powerful parallels between child migrants in 1938 Austria and at America’s southern border in 2019, evoking the tragic universality of war’s innocent young victims.

In her compassionate novel, Allende draws powerful parallels between child migrants in 1938 Austria and at America’s southern border in 2019, evoking the tragic universality of war’s innocent young victims. Samuel Adler is only five when his desperate mother, her home and world destroyed during Kristallnacht in Vienna, places him on a Kindertransport train to England. The antisemitic violence his family experiences feels visceral and immediate on the page.

Decades later, in 1981, Leticia Cordero arrives in the United States with her father, the sole survivors of their immediate family after a massacre in their El Salvadoran village. Later, in 2019, seven-year-old Anita Díaz and her mother, Marisol, are victims of the Trump administration’s family separation policies after they cross from Mexico into Arizona, fleeing a threatening home environment in El Salvador.

All these stories converge during the pandemic, starting when social worker Selena Durán gets lawyer Frank Angileri to take Anita’s case pro bono and help reunite her with Marisol, who may have been deported. By then, Samuel is an 86-year-old widower in San Francisco, and if anyone can relate to Anita’s plight firsthand, he can.

Frank’s rapid transformation from suave would-be seducer (he finds Selena very attractive) to conscientious human rights defender is too convenient, and their conversations about immigration policies seem designed to feed readers background information. But all the viewpoints alternate smoothly, and Allende has a particularly delicate touch in depicting children.

Samuel’s journey from Austria to England to America intertwines with his love for music, while young Anita, who is blind, retreats into an imaginary world to cope. Not only does Allende depict the heroic acts people undertake to help underage migrants, but she underscores the courage of those who do so at great risk to themselves.

The Wind Knows My Name was published by Ballantine (US/Can) and Bloomsbury (UK/Australia). It was translated into English by Frances Riddle. This review was cross-posted to the Historical Novel Society's website.

Published on August 08, 2023 06:49

August 2, 2023

The View from Half Dome, set in the 1930s, evokes the splendor of Yosemite National Park

This lovely tale of coming-of-age and intergenerational friendship takes place against the spectacular natural backdrop of Yosemite National Park during the Depression.

This lovely tale of coming-of-age and intergenerational friendship takes place against the spectacular natural backdrop of Yosemite National Park during the Depression. Isabel Dickinson’s dreary life provokes immediate empathy: just sixteen in 1934, she attends high school, cooks, cleans her dingy San Francisco apartment, and watches over her nine-year-old sister while her overworked mother struggles to support the family after Isabel’s dad’s unexpected death. Isabel envies the freedom of her older brother, James, who took a job with the CCC at Yosemite and sends money back to help them pay bills.

After Isabel’s attempt to claim some personal independence ends terribly, she asks a friend to drive her the long distance to James’s campsite, desperate for a new start. This creates some awkwardness – the CCC doesn’t permit visitors – but Enid Michael, the park’s only female ranger and naturalist, offers her a room in the small apartment she shares with her husband, the assistant postmaster.

Enid, a historical figure, led an extraordinary life cultivating Yosemite’s public wildflower garden, writing countless articles about the park that shaped its public perception, and leading popular tourist walks, all under the eye of a sexist supervisor who looked for excuses to fire her. In this novel, Enid’s in her early fifties, an active mountain-climber who shares her considerable knowledge with Isabel.

Enid’s personal story is so interesting that readers may find their attention drawn away from Isabel, but Caugherty sets up a good dynamic between them. While Isabel admires the older woman’s spirit and determination, she dislikes her habit of lavishing food on birds when people elsewhere are starving.

Isabel’s steady path to emotional maturity feels convincing, and the scenes evoking Yosemite’s beauty are poetically described and spiritually invigorating. Young adults will especially enjoy The View from Half Dome, and so will any reader who thirsts for the great outdoors.

This novel was published by Black Rose Writing in April, and I reviewed it for the Historical Novel Society, where it's cross-posted to the HNS website.

Read more about Enid Michael in an article from Backpacker: "The Story of Enid Michael, Yosemite's First Female Naturalist." I'm glad to have had the chance to meet her in the course of reading this novel. And if you'd like to travel-by-novel to Yosemite of nearly a century ago, you'd do well to pick up this book!

Published on August 02, 2023 16:18

July 26, 2023

In I, Julian, Claire Gilbert creates a fictional autobiography for medieval English mystic Julian of Norwich

What would motivate an ordinary medieval woman to withdraw from the world and become an anchoress, vowing to live out her remaining years in a small cell attached to a church and devote her time to spiritual contemplation?

What would motivate an ordinary medieval woman to withdraw from the world and become an anchoress, vowing to live out her remaining years in a small cell attached to a church and devote her time to spiritual contemplation?In her first novel, I, Julian, Claire Gilbert re-creates the spiritually rich, life-affirming voice of Julian of Norwich, the 14th-15th century mystic whose writings are the first known works by a woman in English. Little is known about the particulars of her life, including her birth name, and Gilbert has filled in the gaps with this marvelous historical reconstruction.

At age 30, having narrowly survived a bout of severe illness, Julian began seeing visions of the Passion of Christ and dedicated her remaining days to soul-searching, prayer, and the sharing of what she glimpsed, realizing the importance of her knowledge for others.

Gilbert imagines a plausible autobiography for Julian, from her quiet childhood with her loving parents in a smallholding outside Norwich, through the tragic years of the Black Plague, the steady encouragement of her mother and others, the terrible grief and guilt she endures, and the transformative experience of her visions, or “showings.” Her words are taken down by a trusted Benedictine monk called Thomas.

It becomes an interesting paradox (addressed in full in the story) that Julian’s physical retreat from the world means complete reliance on others to provide for her needs: food, medical help, and the regular supply of writing materials. The author writes beautifully about Julian's religious life as well as her humanity. Through a window from her anchorhold into the church, she gives her confession and participates in religious services; through a curtained window to the outdoors, she converses with spiritual seekers, friends, her maid, and others whose purpose is less benevolent.

In the late 14th century, the followers of John Wycliffe are amassing, seeking to make the Bible more accessible via English translation, and Julian must tread carefully so as not to be associated with the controversial movement (even while quietly pondering its merits). Throughout her long life, both enclosed and not, Julian remains curious and eager to learn more about God’s feelings toward humankind, which she comes to learn is eternally loving.

Readers of Mary Sharratt’s Illuminations and Revelations (about Hildegard of Bingen and Margery Kempe, respectively) will especially want to pick up I, Julian, and it’s also recommended for anyone interested in the lives of accomplished historical women.

I, Julian was published by Hodder Faith in April in the UK; it will be released next month in the US. You can read more about how the author came to write the book in her interview for Jesus College, Cambridge.

Coincidentally, this morning I received Mary Sharratt's latest newsletter in my email; Julian of Norwich is a character in her novel Revelations. Mary will be participating in the Julian650 lecture series on September 2, presenting a Zoom session (free) on "how her research into women’s hidden histories inspired her to showcase Julian and Margery in her acclaimed novel." See more and register here.

Published on July 26, 2023 16:19