Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 13

December 29, 2023

Short takes on nine historical fiction titles I read in 2023 but haven't reviewed here yet

For my last post of 2023, I'm taking a look back at some novels I'd read over the last twelve months but didn't get around to reviewing at the time. I fit all of these in between review assignments since sometimes I need a break, preferring to read without the necessity of taking notes. Still, all of these are books I'd highly recommend, so I wanted to write about them, at least briefly. All were personal purchases or library copies.

Good reading to all of you in the New Year!

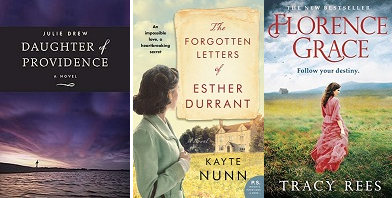

In Julie Drew’s Daughter of Providence, which I bought right after its publication in 2011, a privileged young woman in 1934 coastal Rhode Island discovers how much of her family history has been kept from her. The first surprise is the arrival of her young half-sister, Maria Cristina, who she learns was the product of her late mother’s affair with a man who shared her Portuguese background. A moving coming-of-age story echoing with themes of parental abandonment, labor unrest, family secrets, and reconnecting to one’s heritage.

Countless historical novels use long-hidden love letters to cinch the connection between two parallel narratives. Kayte Nunn’s The Forgotten Letters of Esther Durrant, set on the Isles of Scilly near Cornwall, shows how a talented author can revitalize this trope and make it distinctive and unexpected. Moving between the early 1950s and 2018, the story evokes the rustic coastal beauty of its isolated setting as it follows a marine scientist’s uncovering of a young mother’s forced stay at an island sanitarium.

A blurb on the back of Tracy Rees’ Florence Grace (from fellow novelist Joanna Courtney) describes it as “so very wise, as if it contains half the answers to life.” The quote is actually accurate. Florrie Buckley, an orphaned teenager from a remote corner of Cornwall in 1850, comes into a surprising inheritance and moves to join her newfound relatives in London, where she slowly adjusts to upper-class ways and forms new relationships but remains uniquely herself. Full of entertaining personalities and the protagonist’s lively narration, with a good balance of light and dark.

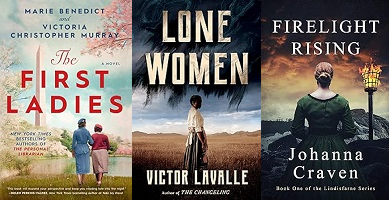

After teaming up for Belle da Costa Greene’s story in The Personal Librarian, which I loved, Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray join forces again for The First Ladies, a dual perspective take on the close friendship between American First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Black civil rights leader and educator Mary McLeod Bethune, nicknamed the “First Lady of the Struggle.” Their interracial bond was controversial, and the authors take a nuanced look at how the pair learn from each other as they make mistakes, grow, and unite to promote equality and justice.

Victor LaValle’s dark historical fantasy Lone Women opens with a shocker: Adelaide Henry, daughter in a Black farming family in 1915 California, flees the scene of her parents’ brutal murder for a homesteading site in Montana, toting a painfully heavy trunk too dangerous to be opened. Let’s just say I had questions. As a “lone woman” in a harsh environment, Adelaide must form alliances with other would-be settlers but needs to discover who to trust. Inventive and not for the squeamish, this novel is a defiantly original take on the multicultural settlement of the American West.

Anyone who’s traveled to the Holy Isle of Lindisfarne in Northumberland knows it’s a special place. First in a trilogy, Johanna Craven’s Firelight Rising takes place there in 1715, as Eva Blake, her siblings, and their families have grudgingly returned after two decades' absence, just as an underground Jacobite movement is stirring. As the Blakes restore their decrepit home, they contend with mysteries of the past and present-day dangers. A highly atmospheric story brimming with romance and mystery and a stellar sense of place.

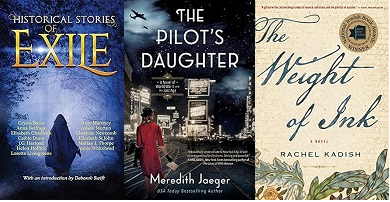

Historical Stories of Exile is an anthology of thirteen short stories, each taking a different angle on its theme. All of the authors are talented historical novelists, and their contributions provide an appealing assortment of settings. Among my favorites were Anna Belfrage’s “The Unwanted Prince,” the heartbreaking true story of a young boy forced to part from his home and loving mother; Cryssa Bazos’ “The Exiled Heart,” retelling the love story between Prince Rupert of the Palatinate and his jailer’s daughter in Austria; Elizabeth St.John’s “Into the Light,” a 17th-century tale of religious disharmony and new beginnings; and Amy Maroney’s “Last Hope for a Queen,” evoking the valiant spirit of Queen Charlotta of Cyprus in the 15th century.

The Pilot’s Daughter by Meredith Jaeger is another dual-narrative story, split between the late WWII years and Jazz Age New York. An office girl at the San Francisco Chronicle, recently informed of her pilot father’s MIA status, comes upon love letters intimating that he’d had an affair. For answers, she turns to her aunt Iris, who has her own secret past as one of Ziegfeld’s dancers in the ‘20s. An engrossing novel about meeting life on its own terms, partly inspired by a real-life crime, the murder of the flapper called the “Broadway Butterfly.”

The Weight of Ink by Rachel Kadish tightly interweaves the stories of two modern academics, a stern older woman and a male American grad student who's used to charming his way into people's good graces, with that of a young Sephardic Jewish woman who handles correspondence for a blind rabbi in exile in Restoration-era London. As the modern pair uncover details about the scribe who signed herself “Aleph,” a deeper succession of mysteries unfolds. Over 500 pages long, brilliant on a sentence level and in its entirety, this National Jewish Book Award winner somehow achieves thriller-like pacing as it celebrates the undeniable quest for learning and delves into perennial human themes. This is right up there with A.S. Byatt’s Possession in my view, and more accessible. A magnificent read.

Good reading to all of you in the New Year!

In Julie Drew’s Daughter of Providence, which I bought right after its publication in 2011, a privileged young woman in 1934 coastal Rhode Island discovers how much of her family history has been kept from her. The first surprise is the arrival of her young half-sister, Maria Cristina, who she learns was the product of her late mother’s affair with a man who shared her Portuguese background. A moving coming-of-age story echoing with themes of parental abandonment, labor unrest, family secrets, and reconnecting to one’s heritage.

Countless historical novels use long-hidden love letters to cinch the connection between two parallel narratives. Kayte Nunn’s The Forgotten Letters of Esther Durrant, set on the Isles of Scilly near Cornwall, shows how a talented author can revitalize this trope and make it distinctive and unexpected. Moving between the early 1950s and 2018, the story evokes the rustic coastal beauty of its isolated setting as it follows a marine scientist’s uncovering of a young mother’s forced stay at an island sanitarium.

A blurb on the back of Tracy Rees’ Florence Grace (from fellow novelist Joanna Courtney) describes it as “so very wise, as if it contains half the answers to life.” The quote is actually accurate. Florrie Buckley, an orphaned teenager from a remote corner of Cornwall in 1850, comes into a surprising inheritance and moves to join her newfound relatives in London, where she slowly adjusts to upper-class ways and forms new relationships but remains uniquely herself. Full of entertaining personalities and the protagonist’s lively narration, with a good balance of light and dark.

After teaming up for Belle da Costa Greene’s story in The Personal Librarian, which I loved, Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray join forces again for The First Ladies, a dual perspective take on the close friendship between American First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Black civil rights leader and educator Mary McLeod Bethune, nicknamed the “First Lady of the Struggle.” Their interracial bond was controversial, and the authors take a nuanced look at how the pair learn from each other as they make mistakes, grow, and unite to promote equality and justice.

Victor LaValle’s dark historical fantasy Lone Women opens with a shocker: Adelaide Henry, daughter in a Black farming family in 1915 California, flees the scene of her parents’ brutal murder for a homesteading site in Montana, toting a painfully heavy trunk too dangerous to be opened. Let’s just say I had questions. As a “lone woman” in a harsh environment, Adelaide must form alliances with other would-be settlers but needs to discover who to trust. Inventive and not for the squeamish, this novel is a defiantly original take on the multicultural settlement of the American West.

Anyone who’s traveled to the Holy Isle of Lindisfarne in Northumberland knows it’s a special place. First in a trilogy, Johanna Craven’s Firelight Rising takes place there in 1715, as Eva Blake, her siblings, and their families have grudgingly returned after two decades' absence, just as an underground Jacobite movement is stirring. As the Blakes restore their decrepit home, they contend with mysteries of the past and present-day dangers. A highly atmospheric story brimming with romance and mystery and a stellar sense of place.

Historical Stories of Exile is an anthology of thirteen short stories, each taking a different angle on its theme. All of the authors are talented historical novelists, and their contributions provide an appealing assortment of settings. Among my favorites were Anna Belfrage’s “The Unwanted Prince,” the heartbreaking true story of a young boy forced to part from his home and loving mother; Cryssa Bazos’ “The Exiled Heart,” retelling the love story between Prince Rupert of the Palatinate and his jailer’s daughter in Austria; Elizabeth St.John’s “Into the Light,” a 17th-century tale of religious disharmony and new beginnings; and Amy Maroney’s “Last Hope for a Queen,” evoking the valiant spirit of Queen Charlotta of Cyprus in the 15th century.

The Pilot’s Daughter by Meredith Jaeger is another dual-narrative story, split between the late WWII years and Jazz Age New York. An office girl at the San Francisco Chronicle, recently informed of her pilot father’s MIA status, comes upon love letters intimating that he’d had an affair. For answers, she turns to her aunt Iris, who has her own secret past as one of Ziegfeld’s dancers in the ‘20s. An engrossing novel about meeting life on its own terms, partly inspired by a real-life crime, the murder of the flapper called the “Broadway Butterfly.”

The Weight of Ink by Rachel Kadish tightly interweaves the stories of two modern academics, a stern older woman and a male American grad student who's used to charming his way into people's good graces, with that of a young Sephardic Jewish woman who handles correspondence for a blind rabbi in exile in Restoration-era London. As the modern pair uncover details about the scribe who signed herself “Aleph,” a deeper succession of mysteries unfolds. Over 500 pages long, brilliant on a sentence level and in its entirety, this National Jewish Book Award winner somehow achieves thriller-like pacing as it celebrates the undeniable quest for learning and delves into perennial human themes. This is right up there with A.S. Byatt’s Possession in my view, and more accessible. A magnificent read.

Published on December 29, 2023 11:41

December 24, 2023

Season's Readings: A compilation of favorite historical novel lists from 2023

I feel like I've been neglecting this blog over the last week. It's been a busy semester at the library, and I've also been spending a lot of time reading and reviewing novels that won't be published until 2024. These will be appearing here later. For now, I thought I'd post links to the "best books of 2023" roundups I've found that cover historical novels.

The New York Times has their selection of the best historical fiction from 2023. This is a gift article, so you can read it even if you don't subscribe. Unsurprisingly, most of these ten are literary fiction. Paul Harding's This Other Eden and Daniel Mason's North Woods would be on my list too. There are some others on the list that I struggled with. For example, I found The Fraud alternately compelling and confusing, since it's very dense, and the nonlinear structure left me feeling lost at times. But I can understand its appeal, and I'm very glad that the NYT has been covering historical fiction regularly.

The historical fiction category at NPR's Books We Love is a perennial favorite since the books fall across many subgenres and age categories. And there are always novels here I haven't come across before.

The Sunday Times offers a dozen best historical novels of 2023. This is probably paywalled unless you have an account, so I'll give some highlights. Elodie Harper's The Temple of Fortuna, third in her trilogy about a woman from a Pompeii brothel, is on the list. Book 1, The Wolf Den, was excellent, and I'm looking forward to the next two. There's also Elizabeth Fremantle's Disobedient, about Artemisia Gentileschi, and Laura Shepherd-Robinson's The Square of Sevens, set in Georgian England.

Crimereads has their best historical fiction of 2023. They describe their picks as historical mysteries and thrillers, but their definition seems broad; it encompasses historical fantasy adventure novels, a swashbuckling pirate story (Katherine Howe's A True Account), The Square of Sevens again, and Cheryl A. Head's Time's Undoing, a dual-period story about unearthing racial injustice, which I'd read from a library copy.

The Toronto Star lists just five books, including Emma Donoghue's Learned by Heart, about the young Anne Lister, and Janie Chang's The Porcelain Moon, covering a little-known angle on WWI-era France.

Shepherd.com has been asking authors to name the best books they read this year. They compiled the results, sorted them by category, and came up with a list of the 100 best historical novels of 2023. Many of these are older titles, and it'd be a stretch to call some of them historical fiction. But it is a wide-ranging, diverse list of choices. You can also narrow it down to those titles published this year.

And the Goodreads Choice Awards for 2023 in the historical fiction category. There's some overlap between this list and the ones linked above -- like James McBride's The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store and Isabel Allende's The Wind Knows My Name -- but not much. The overall winner is Emilia Hart's Weyward.

If you have other lists to share, please let me know.

Merry Christmas to all who celebrate! I'll be back after the holiday with more reviews and historical fiction news.

Published on December 24, 2023 05:41

December 14, 2023

The Other Princess reveals the life story of Queen Victoria's African-born goddaughter

Novels that trace an entire life can show extraordinary depth of character as the protagonists adjust to shifts in circumstance and mature physically and emotionally. The Other Princess is such a book, and its narrator, Sarah Forbes Bonetta, endures more trials than most. Hers is a life of extremes: enslavement, violence, loss, and loneliness, but also friendship, love, and great privilege, accompanied by countless restrictions on her behavior and choices. As wonderfully conveyed by Bryce, Sarah navigates the ripples and swells of her life with grace, always confident in her innate worthiness.

Novels that trace an entire life can show extraordinary depth of character as the protagonists adjust to shifts in circumstance and mature physically and emotionally. The Other Princess is such a book, and its narrator, Sarah Forbes Bonetta, endures more trials than most. Hers is a life of extremes: enslavement, violence, loss, and loneliness, but also friendship, love, and great privilege, accompanied by countless restrictions on her behavior and choices. As wonderfully conveyed by Bryce, Sarah navigates the ripples and swells of her life with grace, always confident in her innate worthiness.Born into a royal family of the Egbado people in West Africa in 1843, and named Aina by her father (“child of a difficult birth”), she is orphaned at five, when the warriors of King Gezo of Dahomey attack her homeland, and gets transferred to a slave camp. Several seasons later, a British naval commander saves her from ritual sacrifice with the aim of bringing her to England and gifting her to Queen Victoria. As she grows up amid Commander Forbes’s family, the girl renamed Sarah, meaning “princess,” comes to appreciate life’s finer things, becoming a talented pianist and befriending Princess Alice on her regular visits to Windsor Castle to see the Queen. However, a permanent home eludes her.

The story principally covers Sarah’s childhood and adolescence, since this formative time impacts the woman she becomes. As she moves across years and places, from various British locales to Sierra Leone and back, her voice feels achingly authentic, full of strength and pride but also vulnerability; she determines to find purpose in an existence where she’s seen as an outsider or novelty. Her relationship with Africa, the source of both her childhood trauma and her royal heritage, is rendered with remarkable complexity. A beautifully resonant biographical novel about a noteworthy figure.

Denny S. Bryce's The Other Princess appeared from William Morrow in October. In the UK, the publisher is Allison & Busby. I reviewed it initially for the Historical Novels Review. Another historical novel based on the life of Sarah Forbes Bonetta is Anni Domingo's Breaking the Maafa Chain, which imagines a sister for Sarah who is transported to America as part of the transatlantic slave trade.

Published on December 14, 2023 16:07

December 9, 2023

Jessie Burton's feminist Medusa flips the script on an ancient Greek myth

Originally published in 2022 for young adults, Burton’s feminist reboot of Medusa’s story has been reissued for the adult market, where mythological re-imaginings flourish.

Originally published in 2022 for young adults, Burton’s feminist reboot of Medusa’s story has been reissued for the adult market, where mythological re-imaginings flourish. After her terrible transformation four years earlier, Medusa, now 18, and her immortal older sisters self-exiled to a deserted island, seeking peace. When Medusa observes a beautiful stranger anchoring his boat, she foresees a potential end to her loneliness.

She and the boy, Perseus, grow close while exchanging personal histories, even though Medusa gives him a false name and doesn’t let him see her. Each draws back from revealing their ultimate secret—for Medusa, her head of multicolored snakes; for Perseus, the deadly purpose that led him there. A reckoning with the truth awaits.

Burton compassionately humanizes her protagonist, a rape survivor yearning for the normal life she can never have, in unambiguous, occasionally poetic contemporary language as Medusa grows in self-confidence. While not as substantial as Natalie Haynes’

Stone Blind

(2023), this short novel of betrayal and destiny, which questions who the myth’s real monsters are, grants Medusa a well-deserved, empowering finale.

Burton compassionately humanizes her protagonist, a rape survivor yearning for the normal life she can never have, in unambiguous, occasionally poetic contemporary language as Medusa grows in self-confidence. While not as substantial as Natalie Haynes’

Stone Blind

(2023), this short novel of betrayal and destiny, which questions who the myth’s real monsters are, grants Medusa a well-deserved, empowering finale.YA recommendation: Medusa’s narrative encapsulates the themes of the #MeToo movement in an honest, vulnerable voice that YAs can easily relate to.

Medusa was published (or I should say, republished) in paperback by Bloomsbury this month. I wrote this review for Booklist's November 1st issue. The most recent cover is at the top; the original YA version is further down. The original indicates it contains illustrations, although these weren't there in the version I read. It's not typical that YA novels are reissued for adults, though this novel could work either way. Whether Burton's retelling is truly historical fiction (of the historical fantasy variety) is open to debate, since the story feels more timeless than ancient. There are references to specific places, but little sense of the historical past.

Burton is also the author of The Miniaturist , its sequel The House of Fortune , and The Muse (links to my reviews).

Published on December 09, 2023 06:45

December 1, 2023

Resistance and memory: Lauren Grodstein's We Must Not Think of Ourselves

Acts of resistance take many forms. For the Jews confined in the Warsaw Ghetto by the Nazis in November 1940, conditions are miserable: cramped living quarters, food shortages, mandatory curfews, increasing restrictions, harsh abuses stemming from pure bigotry. But these people are determined to embrace life, even as it becomes clear the world won’t be rescuing them. “It is up to us to write our own history… Deny the Germans the last word,” says organizer Emanuel Ringelblum, in recruiting the narrator of this penetrating novel to his clandestine archival team.

Acts of resistance take many forms. For the Jews confined in the Warsaw Ghetto by the Nazis in November 1940, conditions are miserable: cramped living quarters, food shortages, mandatory curfews, increasing restrictions, harsh abuses stemming from pure bigotry. But these people are determined to embrace life, even as it becomes clear the world won’t be rescuing them. “It is up to us to write our own history… Deny the Germans the last word,” says organizer Emanuel Ringelblum, in recruiting the narrator of this penetrating novel to his clandestine archival team.As a recorder for the Oneg Shabbat (“joy of the Sabbath”) project, Adam Paskow, a 42-year-old widower, agrees to interview his fellow Jews about their daily lives and histories, whatever they witness in the ghetto and choose to reveal. Adam, an English teacher who continues his classes in the basement of a destroyed cinema, is an affable fellow. Having been surprised into sharing a small apartment with two families, he finds his interviewees close by.

The children’s accounts are simultaneously poignant and delightful. While young boys smuggle food in from the outside, keeping their families alive, they remain amusingly disinterested in adult issues and problems, including Adam’s nosy questions. And through the unavoidable intimacy of their shared living space, Adam grows close to Sala Wiskoff, a married mother of two who’s resourceful, caring, and witty. Still in possession of his late wife’s valuable jewelry, Adam clings to it, realizing its value as a future bargaining chip during desperate times.

The Oneg Shabbat was a real-life documentary project, a unique example of cultural resistance during the Holocaust in Poland. Grodstein movingly re-creates the circumstances behind its creation, capturing the dire atmosphere of the Ghetto and the richly developed, distinctive lives of the people trapped within its walls. Among recent WWII-era fiction, this is a memorable standout.

We Must Not Think of Ourselves was published by Algonquin Books this week. I reviewed it from an Edelweiss e-copy for the Historical Novels Review. The novel, the author's first work of historical fiction, is the December 2023 pick for the Read with Jenna book club on the TODAY show.

Read and view more about the Oneg Shabbat underground archive at Yad Vashem.

Published on December 01, 2023 12:26

November 25, 2023

Experience a courageous woman's life in early Maine with Ariel Lawhon's The Frozen River

Spanning the winter of 1789–90 in Hallowell, Maine, from the freezing of the Kennebec River to its late thaw, Lawhon’s outstanding sixth novel is based on the actual life of frontier midwife Martha Ballard, who recorded daily diary entries about her household and career.

Spanning the winter of 1789–90 in Hallowell, Maine, from the freezing of the Kennebec River to its late thaw, Lawhon’s outstanding sixth novel is based on the actual life of frontier midwife Martha Ballard, who recorded daily diary entries about her household and career. Called to examine the body of Joshua Burgess after it was retrieved from icy waters, Martha recognizes the telltale signs of hanging. Burgess and another man, a local judge, had been accused of raping a young pastor’s wife four months earlier, and Martha believes her account unquestioningly. She also guesses the two crimes are connected.

A sage, strong presence at 54, Martha is an extraordinary character. Devoted to her patients and her six surviving children, mostly young adults with complicated love lives, she battles subjugation by a Harvard-educated doctor who dares to think her incapable.

Although this isn’t a traditional detective story, Martha’s narrative will capture historical mystery fans’ attention with its dramatic courtroom scenes and emphasis on justice, particularly for women. Flashbacks to Martha’s past add context and generate additional suspense.

Martha’s enduring romance with her supportive husband, Ephraim, is beautifully evoked, and details about the lives of the townspeople make the post-American Revolutionary atmosphere feel fully lived-in. Lawhon’s first-rate tale should entrance readers passionate about early America and women’s history.

The Frozen River will be published on December 5th by Doubleday in the US and Canada. I wrote this review originally for Booklist.

Some other notes:

- Martha Ballard is also the subject of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich's Pulitzer Prize-winning nonfiction history book, A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812 (1990).

- The sexual assault of the young pastor's wife, Rebecca Foster, is based in history, and the real Martha recorded details about it in her diary. I won't say more so as not to give spoilers about the novel's plot.

- Martha and I are about the same age, and it's nice to see an older heroine in historical fiction for a change!

- I've previously read and reviewed two of the author's previous novels, (2020) and I Was Anastasia (2018). I loved Code Name Hélène and think this latest book is even better.

Published on November 25, 2023 07:18

November 21, 2023

Daniel Mason's epic North Woods reveals the interconnectedness of humanity and nature over centuries

From the moment two forbidden lovers – the prospective wife of an abusive minister and a reported troublemaker she ironically met at church – flee their repressive Puritan colony for the remote woods of western Massachusetts, the cabin they build in a mountain clearing becomes the setting for an astonishing collection of events across the centuries.

From the moment two forbidden lovers – the prospective wife of an abusive minister and a reported troublemaker she ironically met at church – flee their repressive Puritan colony for the remote woods of western Massachusetts, the cabin they build in a mountain clearing becomes the setting for an astonishing collection of events across the centuries. In twelve chapters that press forward in time and evoke the different seasons, Mason reveals the transformative magic inherent in an ordinary place. Humanity and nature intermix, spurring small and large changes, and the layers of the past remain with us, albeit occasionally taking surprising forms.

While the time periods aren’t formally signposted, each can be determined through the reading, and the chapters show impressive virtuosity in terms of period-suitable language, format, and characterization. In the anonymous “Nightmaids Letter,” a young wife who survives an Indian attack describes a scene of attempted vengeance and the shocking aftermath. An English veteran of the French and Indian War dedicates his life to his apple orchard; his twin daughters grow old while attempting to continue his legacy.

Deep human emotion winds through the pages: loneliness, jealousy, passion, family ties, concealed and thwarted desire, along with beautiful reflections on the natural world, from the echo of songbirds to death and decay. A painter’s ongoing letters to his writer friend are among the most poignant sections.

Deep human emotion winds through the pages: loneliness, jealousy, passion, family ties, concealed and thwarted desire, along with beautiful reflections on the natural world, from the echo of songbirds to death and decay. A painter’s ongoing letters to his writer friend are among the most poignant sections.Over the novel’s course, it feels especially rewarding (with some great “aha” moments for the reader) to see earlier episodes reappear as historical artifacts or tales down the road. Just like in life, the process of historical discovery can be incredible or frustrating, since mysteries from the past sometimes stay that way.

The last two chapters, full of revelation, put the entire story-landscape into greater and more wondrous perspective. This wisely compassionate and refreshingly different literary epic is an excellent read.

North Woods was published by Random House in the US and Canada, and John Murray in the UK. I reviewed it for November's Historical Novels Review from a NetGalley copy. I'm already seeing this novel on many "best of" lists for 2023. The North American cover, top left, reflects one aspect of the story, but I'm not fond of it. The UK cover is somewhat better. I look forward to seeing what the paperback edition will look like.

Published on November 21, 2023 14:32

November 16, 2023

The 2023 Goodreads Choice Awards historical fiction nominees are up – but look in other categories, too

The initial round of the 2023 Goodreads Choice Awards is open for voting through Sunday, November 26th. Have you made your selections yet?

I always participate, even though I agree with the sentiment that it's primarily a popularity contest (which Goodreads itself says; they include in their guidelines that "our goal is to have the Goodreads Choice Awards reflect the books that are most popular with our members"). There's no longer an option to provide write-in votes, so what you see within the categories are the nominees.

It is nice that they always include a historical fiction category. I've only read three of them and would like to read the others. This year, there seems less of an issue with novels that seemed a stretch too late for historical fiction (like, set primarily in the 1980s or 1990s) being included in this category.

A note, though, that if you want to cast your votes for historical fiction, you should make sure to scan the other fiction categories to see what's there. For the novels above which are debuts, you'll find most within the Debut Novel category as well.

Historical fiction frequently overlaps with other genres, creating genre-blends. I nearly missed that Kate Morton's Homecoming was in the Mystery category, for instance. Within Horror, you'll find Victor Lavalle's Lone Women, which is a great example of that genre as well as historical fiction (an excellent, original, very strange novel I may review later), as well as Vampires of El Norte by Isabel Cañas and The Reformatory by Tananarive Due. I also noticed that Isabel Allende's The Wind Knows My Name, another dual-time novel but set mostly in the '80s and after, is placed with Historical Fiction rather than in the general Fiction category.

If you're looking to find the ancient myth retellings so popular in historical fiction lately, you won't find them in that category; instead, you'll find them under Fantasy. This makes sense for Natalie Haynes' Stone Blind, about Medusa, but one could argue that Jennifer Saint's Atalanta and Costanza Casati's Clytemnestra fit better as historical fiction, if you had to choose one and only one category for them. For me, the decision hinges on whether the author has made the effort to re-create a realistic historical atmosphere of ancient Greece, or whether the novel is primarily set in the realm of myth.

I always find it interesting to see how others choose to categorize novels. Voting for the final round for the awards will begin on November 28th.

I always participate, even though I agree with the sentiment that it's primarily a popularity contest (which Goodreads itself says; they include in their guidelines that "our goal is to have the Goodreads Choice Awards reflect the books that are most popular with our members"). There's no longer an option to provide write-in votes, so what you see within the categories are the nominees.

It is nice that they always include a historical fiction category. I've only read three of them and would like to read the others. This year, there seems less of an issue with novels that seemed a stretch too late for historical fiction (like, set primarily in the 1980s or 1990s) being included in this category.

A note, though, that if you want to cast your votes for historical fiction, you should make sure to scan the other fiction categories to see what's there. For the novels above which are debuts, you'll find most within the Debut Novel category as well.

Historical fiction frequently overlaps with other genres, creating genre-blends. I nearly missed that Kate Morton's Homecoming was in the Mystery category, for instance. Within Horror, you'll find Victor Lavalle's Lone Women, which is a great example of that genre as well as historical fiction (an excellent, original, very strange novel I may review later), as well as Vampires of El Norte by Isabel Cañas and The Reformatory by Tananarive Due. I also noticed that Isabel Allende's The Wind Knows My Name, another dual-time novel but set mostly in the '80s and after, is placed with Historical Fiction rather than in the general Fiction category.

If you're looking to find the ancient myth retellings so popular in historical fiction lately, you won't find them in that category; instead, you'll find them under Fantasy. This makes sense for Natalie Haynes' Stone Blind, about Medusa, but one could argue that Jennifer Saint's Atalanta and Costanza Casati's Clytemnestra fit better as historical fiction, if you had to choose one and only one category for them. For me, the decision hinges on whether the author has made the effort to re-create a realistic historical atmosphere of ancient Greece, or whether the novel is primarily set in the realm of myth.

I always find it interesting to see how others choose to categorize novels. Voting for the final round for the awards will begin on November 28th.

Published on November 16, 2023 15:00

November 13, 2023

Jon Clinch's The General and Julia showcases the multifaceted nature of an American icon

The most celebrated general of the Union army, he negotiated the Confederacy’s surrender wearing an ordinary soldier’s garb. Born to an abolitionist father, he married a Missouri slaveowner’s daughter who kept an enslaved Black woman as her maid. Having relinquished his military pension to become America’s eighteenth president, he lost his vast savings to a conniving fraudster.

The most celebrated general of the Union army, he negotiated the Confederacy’s surrender wearing an ordinary soldier’s garb. Born to an abolitionist father, he married a Missouri slaveowner’s daughter who kept an enslaved Black woman as her maid. Having relinquished his military pension to become America’s eighteenth president, he lost his vast savings to a conniving fraudster. Epic in perspective and feeling without being biographically comprehensive, Clinch’s stellar character-portrait of Ulysses S. Grant invites readers to ponder this national icon and the seemingly paradoxical facets of his nature.

In 1885, afflicted with throat cancer likely caused by habitual cigar-smoking, Grant reconsiders important life moments while penning his memoirs, desperately hoping its proceeds will rescue his beloved wife, Julia, and family from destitution after his impending death.

Many chapters (or groups of them) could serve as exceptional short stories; taken together, they comprise a memorable picture. We see Grant from within and through others’ eyes, as scenes of sublime prose conjure Grant’s strategic brilliance at Chattanooga, the awe he inspires, and his devotion to Julia and their children and grandchildren.

We also witness instances of frustrating passivity and naivete plus his evolving views on slavery, which evoke regret over his past ambivalence. While the story shifts around in time, it never loses its arc. Superb historical fiction.

Jon Clinch's The General and Julia will be published by Simon & Schuster tomorrow, November 14; I contributed this starred review for Booklist's Oct. 1 issue. The novel also received starred reviews in Library Journal and Kirkus, and it's one of my favorite books this year.

Published on November 13, 2023 03:30

November 7, 2023

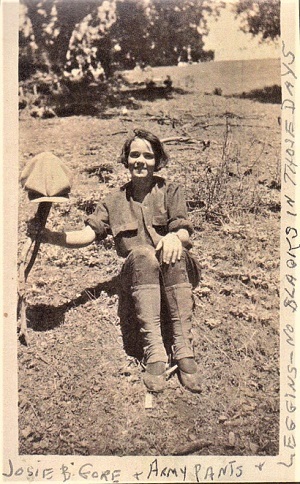

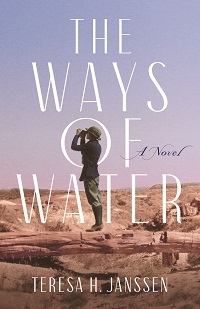

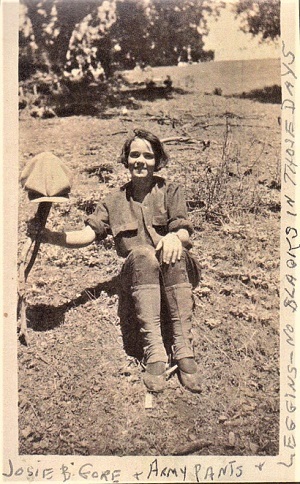

Telling a Family Story, an essay by Teresa H. Janssen, author of The Ways of Water

Teresa H. Janssen is here today with a post about transforming family history into historical fiction. Her grandmother, Josie Belle Gore, inspired the main characters of her debut novel, The Ways of Water, which is published today. The photos below are from her family archive.

~

Telling a Family StoryTeresa H. Janssen

Many of us are astounded by the courage, tenacity, and optimism of our ancestors. Other times, after learning of their disappointments and misfortune, we cringe at their choices and misguided enthusiasm, sometimes due to a lack of information or resources. Like us, they made decisions based on the best of their knowledge. I experienced both wonder and despair while doing research for my debut historical novel, The Ways of Water, inspired by the early life of my grandmother, Josie Belle Gore.

Many of us are astounded by the courage, tenacity, and optimism of our ancestors. Other times, after learning of their disappointments and misfortune, we cringe at their choices and misguided enthusiasm, sometimes due to a lack of information or resources. Like us, they made decisions based on the best of their knowledge. I experienced both wonder and despair while doing research for my debut historical novel, The Ways of Water, inspired by the early life of my grandmother, Josie Belle Gore.

It all began on a windy January day when I arrived at New Mexico's Jornada del Muerto (southeast of Truth or Consequences) in search of the graves of my great grandparents. All that I could find were a few wooden posts in the lonely desert, remnants of the cemetery of Cutter, now barely a ghost town, but once a thriving railroad and mining community of three thousand inhabitants. I was overcome by the tragedy of my great grandmother's death there in 1916 at the age of thirty-six. She left seven children behind, one an infant; her third child, my grandmother.

The Gore Siblings

The Gore Siblings

While standing in the blowing sand that day, I remembered a lecture by Maya Angelou that I attended when I was sixteen years old. She had spoken of the sacrifices of our ancestors, made in hopes of better lives for future generations. I didn’t want my forebears’ trials to go unappreciated or forgotten.

As I began to research and write their tale, I became aware that there was a larger story to be told. The Jornada del Muerto is now littered with ghost towns, with few trains passing through. Historic sections of Las Cruces and Tucson have been razed. Bisbee, Arizona is a fraction of its former size. One of our family ranches is now part of the White Sands missile base.

I began by researching the boom-and-bust opportunities that had lured many to that region—the acquisition of land by mining companies, railroads, ranch syndicates, and homesteaders—often made possible by unfair treaties, land seizures, and the displacement of indigenous peoples.

Gores and Grahams, Jornada del Muerto

Gores and Grahams, Jornada del Muerto

I was astounded by the social, political, and cultural changes my grandmother and her family lived through. My great grandfather was a steam locomotive engineer and my great grandmother, a seamstress. I researched the technological breakthroughs during the first two decades of the twentieth century—faster trains with better safety standards, the growing popularity of the Singer sewing machine, expansion of Western Union and its telegraph lines, advent of the automobile with mass production of the Model-T, increased electrification of towns and household appliances. These changes were as liberating and unsettling for many who lived during this time, as recent technological shifts are for some of us today.

My grandmother lived in Chihuahua during the onset of the Mexican Revolution and survived two epidemics—tuberculosis and influenza. She was a teen during WWI and then chopped off her hair and the hem of her skirt in the heady post-war Twenties. She witnessed the advent of women’s suffrage, as well as cultural shifts during prohibition. As I learned more about her experiences, my admiration for her grew. A history geek, it was at times hard for me to take a pause in the research to get back to writing the story.

Josie Gore hiking near geyser on honeymoon, 1924

Josie Gore hiking near geyser on honeymoon, 1924

The Ways of Water originated as fragments of family oral history, yet to bring it to life, I decided to tell the story in first person, from the perspective of my grandmother. I had interviewed her while she was still living and had a collection of notes to get me started. I soon became aware that I had not asked enough questions. There were gaps in the timeline, too little detail, vagaries I had to guess at, and sometimes different versions of an event. I realized that to create an account with voice and emotion, I would need to write my grandmother’s early life as historical fiction. At that point, I had the liberty to create scenes and imagine conversations, and alter names, locations, and time, when necessary, to develop an engaging and cohesive narrative.

The Ways of Water tells the story of Josie Belle Gore, who, after her family was separated by circumstances beyond her control, was forced to make her way alone through the desert West to eventually arrive in San Francisco in the early 1920s. This is a story of loss and redemption, hope and forgiveness, set in the rugged beauty of the Southwest during a turbulent period of American history.

Excerpts, The Ways of Water

"My story is twined, like rope, with that of my kin. The first strand began to fray when Mama, a city girl from Austin, fell in love with a Louisiana railroad man. As Papa ran the steam locomotives across the great desert of the West, Mama followed him. Steam engines always follow water, and we did, too."

“Life, like a river, can take some sharp twists and turns. People can shift as much as a water’s course. There are reasons I broke my promises. I want them to be known," says Josie Belle Gore as she begins her tale.

Bio:

author Teresa H. Janssen

author Teresa H. Janssen

(David Conklin Photography)Teresa H. Janssen studied history and French at Gonzaga University and has an M.A. in Linguistics from the University of Washington. She taught for over twenty years in refugee programs, higher ed, and public high school. Her fiction and essays have appeared in a variety of literary journals, including Zyzzyva, Chautauqua, Eastern Iowa Review, and Under the Sun, and in the anthologies, Art in the Time of Unbearable Crisis and Offerings: A Spiritual Poetry Anthology. She was a finalist for Bellingham Review’s Annie Dillard Prize and won the Norman Mailer/NCTE Award in nonfiction. She lives with her husband in Washington state where she writes, hikes, and tends a small orchard. She can be found online at www.teresahjanssen.com.

Book details:

The Ways of Water: A Novel by Teresa H. JanssenPublished by She Writes Press, Nov. 7, 2023ISBN: 978-1-64742-583-8

~

Telling a Family StoryTeresa H. Janssen

Many of us are astounded by the courage, tenacity, and optimism of our ancestors. Other times, after learning of their disappointments and misfortune, we cringe at their choices and misguided enthusiasm, sometimes due to a lack of information or resources. Like us, they made decisions based on the best of their knowledge. I experienced both wonder and despair while doing research for my debut historical novel, The Ways of Water, inspired by the early life of my grandmother, Josie Belle Gore.

Many of us are astounded by the courage, tenacity, and optimism of our ancestors. Other times, after learning of their disappointments and misfortune, we cringe at their choices and misguided enthusiasm, sometimes due to a lack of information or resources. Like us, they made decisions based on the best of their knowledge. I experienced both wonder and despair while doing research for my debut historical novel, The Ways of Water, inspired by the early life of my grandmother, Josie Belle Gore. It all began on a windy January day when I arrived at New Mexico's Jornada del Muerto (southeast of Truth or Consequences) in search of the graves of my great grandparents. All that I could find were a few wooden posts in the lonely desert, remnants of the cemetery of Cutter, now barely a ghost town, but once a thriving railroad and mining community of three thousand inhabitants. I was overcome by the tragedy of my great grandmother's death there in 1916 at the age of thirty-six. She left seven children behind, one an infant; her third child, my grandmother.

The Gore Siblings

The Gore SiblingsWhile standing in the blowing sand that day, I remembered a lecture by Maya Angelou that I attended when I was sixteen years old. She had spoken of the sacrifices of our ancestors, made in hopes of better lives for future generations. I didn’t want my forebears’ trials to go unappreciated or forgotten.

As I began to research and write their tale, I became aware that there was a larger story to be told. The Jornada del Muerto is now littered with ghost towns, with few trains passing through. Historic sections of Las Cruces and Tucson have been razed. Bisbee, Arizona is a fraction of its former size. One of our family ranches is now part of the White Sands missile base.

I began by researching the boom-and-bust opportunities that had lured many to that region—the acquisition of land by mining companies, railroads, ranch syndicates, and homesteaders—often made possible by unfair treaties, land seizures, and the displacement of indigenous peoples.

Gores and Grahams, Jornada del Muerto

Gores and Grahams, Jornada del MuertoI was astounded by the social, political, and cultural changes my grandmother and her family lived through. My great grandfather was a steam locomotive engineer and my great grandmother, a seamstress. I researched the technological breakthroughs during the first two decades of the twentieth century—faster trains with better safety standards, the growing popularity of the Singer sewing machine, expansion of Western Union and its telegraph lines, advent of the automobile with mass production of the Model-T, increased electrification of towns and household appliances. These changes were as liberating and unsettling for many who lived during this time, as recent technological shifts are for some of us today.

My grandmother lived in Chihuahua during the onset of the Mexican Revolution and survived two epidemics—tuberculosis and influenza. She was a teen during WWI and then chopped off her hair and the hem of her skirt in the heady post-war Twenties. She witnessed the advent of women’s suffrage, as well as cultural shifts during prohibition. As I learned more about her experiences, my admiration for her grew. A history geek, it was at times hard for me to take a pause in the research to get back to writing the story.

Josie Gore hiking near geyser on honeymoon, 1924

Josie Gore hiking near geyser on honeymoon, 1924The Ways of Water originated as fragments of family oral history, yet to bring it to life, I decided to tell the story in first person, from the perspective of my grandmother. I had interviewed her while she was still living and had a collection of notes to get me started. I soon became aware that I had not asked enough questions. There were gaps in the timeline, too little detail, vagaries I had to guess at, and sometimes different versions of an event. I realized that to create an account with voice and emotion, I would need to write my grandmother’s early life as historical fiction. At that point, I had the liberty to create scenes and imagine conversations, and alter names, locations, and time, when necessary, to develop an engaging and cohesive narrative.

The Ways of Water tells the story of Josie Belle Gore, who, after her family was separated by circumstances beyond her control, was forced to make her way alone through the desert West to eventually arrive in San Francisco in the early 1920s. This is a story of loss and redemption, hope and forgiveness, set in the rugged beauty of the Southwest during a turbulent period of American history.

Excerpts, The Ways of Water

"My story is twined, like rope, with that of my kin. The first strand began to fray when Mama, a city girl from Austin, fell in love with a Louisiana railroad man. As Papa ran the steam locomotives across the great desert of the West, Mama followed him. Steam engines always follow water, and we did, too."

“Life, like a river, can take some sharp twists and turns. People can shift as much as a water’s course. There are reasons I broke my promises. I want them to be known," says Josie Belle Gore as she begins her tale.

Bio:

author Teresa H. Janssen

author Teresa H. Janssen(David Conklin Photography)Teresa H. Janssen studied history and French at Gonzaga University and has an M.A. in Linguistics from the University of Washington. She taught for over twenty years in refugee programs, higher ed, and public high school. Her fiction and essays have appeared in a variety of literary journals, including Zyzzyva, Chautauqua, Eastern Iowa Review, and Under the Sun, and in the anthologies, Art in the Time of Unbearable Crisis and Offerings: A Spiritual Poetry Anthology. She was a finalist for Bellingham Review’s Annie Dillard Prize and won the Norman Mailer/NCTE Award in nonfiction. She lives with her husband in Washington state where she writes, hikes, and tends a small orchard. She can be found online at www.teresahjanssen.com.

Book details:

The Ways of Water: A Novel by Teresa H. JanssenPublished by She Writes Press, Nov. 7, 2023ISBN: 978-1-64742-583-8

Published on November 07, 2023 04:00