Mary Beard's Blog, page 47

March 2, 2013

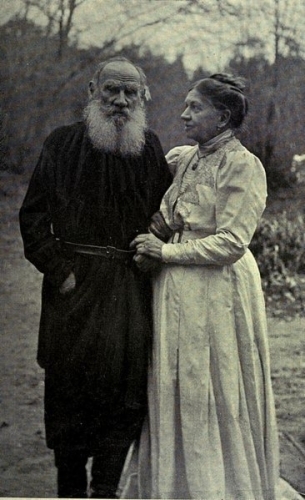

Getting to grips with Tolstoy

I have been spending the weekend some way off my usual patch. When my editor Peter Carson died in January, he had just finished, literally the day before he died, translating Tolstoy's Death of Ivan Ilych and Confession for a US publisher (Norton). It will come out later in the year and I am to write the Introduction.

Don't worry, I am not getting above myself. There is also to be a more specialist essay from a Russian expert. My job is to set the scene -- and also to celebrate, and discuss, Peter's role as translator (on which I have quite a lot of interesting stuff). All the same I thought I needed to do a bit more background work on books concerned and their author. Up to now, my knowledge of Tolstoy has been like many people's I imagine: that is to say, some familiarity with War and Peace and Anna Karenina, and rather less interest in the spiritual, pacificist, social reformer that came later -- in the period when both Ilych and Confession were written.

So I've done a day and half's immersion therapy (with more to come), and of course -- as always happens -- I have begun to regret that I haven't been more interested in all this before.

It's not just that Tolstoy's spiritual journey is rather more intriguing than I expected; though that is part of it. For those that know the book, I am (for example) increasingly surprised that most critics (not all, to be fair) seem to take Confession as a pretty transparent autobiographical account of Tolstoy's spiritual struggles -- when the more I read it against The Death of Ivan Ilyich (and Anna Karenina), the more highly crafted, literary construction it comes to seem.

But I'm most of all gobsmacked by the degree of Tolstoy's celebrity in his later years and the wealth of evidence there is for his life (and death) then. I did, sort of know, about the story of him leaving home in 1910, and abandoning the wife, and then dying on the railway station a few days later at the age of 82. But I hadn't quite realised what a media circus it all was -- or that (quite apart from modern cinema recreations, like The Last Station) so much original film footage had survived, including the death bed and funeral.

And I hadn't quite known of the real life, terrible scenes when his wife was kept out of the room where Tolstoy was, and forced to try to peer in through the window -- until they finally let her in when the old man was already unconscious.

Though I guess that is appropriate enough that a writer who was so preoccupied with death, dying and the impact of death's inevitability on the meaning, should himself have had such a baroque end. I'm now trying to figure how this all goes together with Ivan Ilych and Peter's death too.

***********

On quite another topic, and excuse a family advert, the son has been writing on video games in the Arab world, a more curious subject than you might imagine: click here.

February 27, 2013

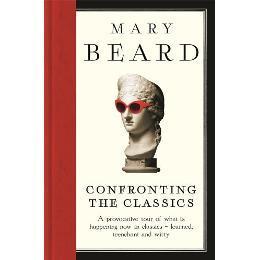

Telling a book by its cover

It would be a gross overstatement to claim that choosing the cover was one of the biggest tasks in writing and producing a book. But it is one of the most memorable ones -- and fun and communal (unlike the rather solitary experience of writing). Everybody from author to editor, artist to publicity person, can put a useful oar in. Does this cover capture what is in the book? Will it encourage people to pick it up in the bookshop? Or linger online?

My book that's just coming out comprises, as a basis, some of the favourite reviews and essays I've written over the last 15 - 20 years. But they have been rewritten, re-edited and reordered to make what I hope is a convincing WHOLE .. which introduces readers (in roughly chronological order, starting from Minoan Knossos and ending with Astérix the Gaul) to the ancient world, and more to the point to what the current debates about it are. What's going on in Classics now? What are people arguing about? (Plug over)

We spent a long time with the cover -- and even with the title.

As you can see here, it started life with a working title of "Classical Traditions" and a rather elegant Piranesi style column on the front. That was fine while the book was still being constructed, but as soon as we had the text, it looked simply wrong. For a start the title looked really conservative -- rather like a homage to the Greeks and Romans, not an engagement with them. To put it another way, it sounded like a book that was going to be good for you, but not hugely enjoyable.. and certainly not remotely argumentative.

And that appeared to be the message of the column capital too. Aesthetically fine -- but where are the people that actually play a rather large part in the text?

Yet we all quite liked the overall idea/concept....

Some of my last, and some of my most enjoyable, discussions with Peter Carson were about precisely this. First thing to get scrapped was the title. We quickly got rid of the PASSIVITY of 'traditions' (even the plural wasnt good enough to rescue it).. and went through a variety of bosh shots: Meeting the Classics, Classics old and new (ugh), Do Classics Matter? Challenging Classics....

Until we all liked "Confronting the Classics", which has more bottle than "Meeting...", and is to be honest what the book is actually about.

So the image...The first idea was to replace that column with a human being of some sort, to keep the nicely elegant neo-Classicism, but to disrupt it slightly, to capture a bit of (what we hoped was) a sense of fun.

The first mock-up was a Roman soldier/Julius Caesar, with a magnificent, punk-style red plume, to match the binding. A step in the right direction, but ever so blokeish -- and possibly a bit too punk to appeal to some potential readers! So we spent one of our last afternoons with Peter, looking at what the artist came up with next. The brief was: keep the jokey feel, but with a slightly more female touch (or at least a slightly less aggressively male touch). In the end, after a glass or two of Pinot, we all agreed on what you now see. So I hope you like it.

Eagle eyes will also spot that the text on the front cover has been lightened up too. Crucially the "B" word has gone... If there is one basic message in the book trade, it has to be "never look as if your claiming your own book is BRILLIANT". Easy to do, but it looks horribly overconfident, and a hostage to fortune.

February 22, 2013

What meat we used to eat

Out at dinner the other evening, we 50-somethings (and more) fell to talking about the food we had, or had not, eaten when we were kids in the (non-metropolitan) UK. It was an object lesson in the speed of dietary change, as well, perhaps, an object lesson in our own social and cultural mobility.

We started with some of the 'nots'.

Top of the list here was olive oil. So far as we could recall, in the late 50s and early 60s olive oil wasn't something you bought at the grocers, but at the chemists. The reason for that is that it wasn't generally used for cooking, but you heated it up and used it to dampen the cotton wool that you put in your ears when you had earache.

It follows that salad dressing was not on the menu either -- or at least not the oil and vinegar variety. What we poured over our unadorned lettuce leaves and tomatoes was Heinz Salad Cream (still on the supermarket shelves but hardly a best seller, I imagine).

And pasta was striking by its absence too, or at least in the Italian dried or fresh variety. It wasnt until we were in our late teens that most of us had tasted anything other than spaghetti out of a tin (Heinz again).

And as for what we did eat?

Here it was in meat (or rather the particular bits of the animal that ended up on our plates) that we saw the biggest difference. Chicken was a luxury not a staple (presumably it was just before the advent of battery farming and antibiotic injections). Instead we regularly ate what we would now call the cheap bits or the cheap beasts: I mean things like tongue, or ox-tail, or chaps (that's pigs' cheeks, remember?) or brisket, or breast of lamb, or black pudding, or pigeon or rabbit....

Some of this we remembered as truly tasty. In fact, I've just rediscovered brisket (thanks to the encouragement of the local butcher) -- and wonderful it is too.

But before we got carried away, we remembered that it wasn't all quite so desirable. There wasn't much enthusiasm round the table for that old staple of tripe and onions (pictured above), nor regret for its passing from our culinary repertoire -- though presumably tripe and other hard-core parts of the cow are still a fairly major constituent, albeit ground-up, of "valu-burgers" (is it better to see what you are eating, or not?)

Can anyone add to this list of recently lost foods....? Kraft processed cheese triangles? Blancmange?

February 18, 2013

Money laundering at the Post Office

This is one of those complaints about the absurdities of modern regulations . . . so if you really can't bear wry moans about modernity, better not read on.

Earlier this week the husband had to acquire a postal order for just over £100. He is going to India and must get a visa. Time was when you just queued up at India House with your cash, left your passport in the morning and picked it up later that day. Now the whole Indian visa operation has been out-sourced, it's shot up in price, and you have to pay by POSTAL ORDER -- a kind of currency that I imagine most people in the land didn't realise still existed.

So the husband trots around to the local sub post office last week to acquire the postal order.

It turns out to be a pricey piece of paper. I scoffed in disbelief when he said it cost £12,50 (didn't he mean 12p?), but checking on the web I discover that there is indeed an admin fee of 12.5% of the value of the order, capped at £12.50. Makes even your credit card look cheap.

Anyway when it comes to paying, he gets his debit card out, only to be told by the woman behind the counter that he must pay in cash. He protests that last time he bought one (also for an Indian visa) he paid by debit card. That was, she retorted, absolutely impossible. It has bever been allowed to buy a postal order with a debit card; he can't be remembering straight. Cash or nothing.

He had no option but to leave the post office and find the nearest bank machine, get the cash and return to the back of the queue and start the whole palaver all over again. (Anyone who knows our local sub post office will know how long that will have taken ....almost longer than it used to take to queue at india House.)

Back home, and still cross, the husband decides to ring up the Post Office customer service line to complain. The man on the other end of the line explains that the woman behind the counter was quite right, you cannot buy a postal order with a debit card. Why? Because of money laundering regulations, he explains.

The husband then plays the over-60s card. He points out that the consequence of this ruling was that he had to go down the road, withdraw a large amount of cash from the hole in the wall (how safe is that?) and then join the back of the queue all over again . . .

Oh, replied the helpful customer service man, there was no need for all that. You could have got £100 cash with your debit card at the Post Office counter, through their card machine, and then used that cash to pay for the postal order (which is presumably what happened the previous time...understandly "misremembered" as "paying with a debit card").

The husband asked that this useful information be passed on to the counter staff at our local sub post office, which the customer service man promised he would do.

But can anyone explain how any of this would help prevent "money laundering"... especially if you can't pay for a Postal Order by debit card, but you can withdraw the cash on the debit card and then use that to buy the Postal Order. The logic is certainly lost on me. And what serious money launderers deal in £100 postal orders anyway?

(Just in case you're thinking that we are terrible old stick in the muds in this house, let me assure you that we do see some advantages in modern technology. If you aren't any longer allowed to go and queue up for your visa at India House, it is quite nice to have reassuring text messages arriving on your mobile, telling you how far your passport has progressed in the system...at extra cost, of course)

February 13, 2013

Man ist was man isst?

I am still finding it hard to get a grip on exactly what is going on in the great horsemeat scandal. Or rather, it seems that significantly different objections are getting lumped together.

For some people it is a consumer/trades description issue: the packet said the contents were made of beef when in fact it was horse, so the consumer (in this case literally) was being cheated. On this line, it would have been just as bad if the packet had been labelled "horse" but the contents had been beef.

For others, it is a question of health and safety. That is to say, it is not just that the contents are wrongly described, but that the illicit horse meat might still carry traces of the harmful chemicals with which the living horses, never intended to enter the food chain, had been injected.

Still others are concerned about the simple fact that it is horsemeat. Mutton masquerading as beef would not have caused such a stir; but we British just don't eat horse -- and so a food taboo has been broken. Most of us know, deep down, that most animals are perfectly nutritious. And it is striking that, so far as I am aware, none of those customers who tucked into their Findus lasagne seem to have had any inkling on the taste buds that something was awry (have we heard from anyone who claims to have said "it didnt taste like beef to me"?). But cultural identity is heavily embedded in the particular range of those animals we choose to put on our plates. For the British that does not include horse or frogs or dog or cat (though I am grateful to a friend who recently reminded me that Elizabeth David referred to a celebratory dish of roast cat in Sardinia).

What is clear, though, is that the whole business is completely mired in the murky international food trade.

From Romania to France, the UK and Ireland, it seems very hard to work out who was knowingly passing off a lump of horsemeat as a joint of beef, and who simply couldn't tell the difference between them whether cooked of uncooked. In fact the tracking of the ingredients of these processed foods we buy in the supermarket back to their source now seems to be the work of squads of international food (and criminal) detectives.

So how do you escape these murky foodways, especially in the meat department? One answer is, of course, to give it up (an option that I was brought up with by a vegetarian mother). The other is to try to eat the real local stuff.

As we were reflecting on these alternatives, the husband remembered a wry but sad little tale from a few years back. Our local butcher, the excellent Wallers of Victoria Avenue, put out a sign in fron of the shop, advertising that they would shortly be selling the meat from the cattle, then still grazing on the nearby common. There was a mini local outcry from quite a number of residents who felt that it was all a bit insensitive to parade the fact that the handsome beasts we enjoyed watching on the common were shortly to be found on our dinner platers. I think Wallers were forced to take the sign down.

years back. Our local butcher, the excellent Wallers of Victoria Avenue, put out a sign in fron of the shop, advertising that they would shortly be selling the meat from the cattle, then still grazing on the nearby common. There was a mini local outcry from quite a number of residents who felt that it was all a bit insensitive to parade the fact that the handsome beasts we enjoyed watching on the common were shortly to be found on our dinner platers. I think Wallers were forced to take the sign down.

But the butcher has had the last laugh. I think most of us would now agree that it is better to have personal acquaintance with what you're eating that be at the mercy of whoever the scammers or cost-cutters may be, bringing you horse dressed up as beef from Romania, via France.

February 12, 2013

The Oldie's pin-up

This is a heartfelt thank-you to the Oldie .. for making me the Oldie's pin-up of the year at their brilliantly louche awards ceremony today.

When I got the invitation to the Oldie of the Year lunch, I have to say that I thought it was a great reward for having hosted an event at the Oldie's Soho Lit. Festival. It wasn't until the management were more than a little concerned to find out that I was really attending the event that I realised that I might have won something. (I took this from what I have read ... ok, lets compare little and large here .. about the Oscars etc: if they get very keen on knowing about the car you are coming by, it means you have won).

The truth is that the whole event was damn brilliant. And if I have ever before sneered at Terry Wogan (which I may have done) please let me take it back. Both he and (the co-host) Richard Ingrams were great forces for pleasure and amusement throughout.

Part of that was the feisty (self-)presentation of the over 60s (or over 60-ish). The guests weren't the grannies and grandpas of the senior railcard adverts, whose life seems to consist only in visiting the younger generation by very long train journeys. These were powerful people, and grey funsters, with projects still underway. I'm sure you know the kind I mean.. Joan Bakewell, Maureen Lipman, Libby Purves, Lucy Lampton (and that's only a few of the ladies).

Anyway the prizes were a wonderful array. The top "Golden Oldie" award went to Michael Heseltine (just think, I thought to myself, how I hated him when I was young, and now . . .). The others were a centenarian Marathon runner (who came with his trainer to speak on his behalf), Trog the cartoonist, the oldest kidney donor in the country,the man who raised the money for the memprial to Bomber Command .. and me.

The fact was that, althought I had got the message that I'd be getting an award, I still hadn't worked out what for. The family betting had been on the Golden Hairbrush award 2013, or the "Oldie award for sartorial idiosyncrasy", vel sim. In a way, they weren't all that wrong.. as it was the "Pin up of the year".

Now in all kinds of ways this is a great joke. And don't for a minute think I am taking it over-seriously. But I can tell you that when you have taken some of the shit that I have over the last weeks (if you dont know, then google for it), this sort of thing, in all its jokey colours, simply warms the heart.

The truth is that I have had huge (e-)mail bags full of support; for which many thanks. But this kind of lighthearted public treatment (started for me, I should say, no less lightheartedly by the admirable Evening Standard) is one of the most effective ways of facing down some of the sillier sorts of sexism that I .. and many others .. have been attacked with. And it's an effective way of having a good time too.

So thank you Oldie! And thank you Standard!

February 9, 2013

New York Review of Books reaches 50

I am just back from a couple of days in New York. I can sense some of you thinking some wry thoughts about this jetsetting life: eurocrat in Brussels one week, then the Big Apple the next . . . not exactly the hardworking academic image you've been trying to give.

I see the point, but I would say this was all a bit punishingly mad, not glam. I'm not allowed (nor would I want) to skip any teaching, so it's a question of fitting five days work into the three that are left etc etc ... BUT, the fact is that I wouldnt have missed the New York trip for the world.

It was the celebrations to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the New York Review of Books. There was a party (filmed by regular reader Martin Scorsese, yes honest), and I was giving a mini lecture at the anniversary symposium.

The New York Review is an extraordinary magazine. It was founded in 1963 in the middle of a journalists' strike which took the New York Times Book Review off the news stands (that's a bit like the story of the London Review which was launched during the Times strike which temporarily removed the TLS). It has been edited ever since the beginning, for all 50 years, by Bob Silvers (Barbara Epstein, the other founding editor, died in 2006).

At the symposium, a group of longstanding contributors -- from Joan Didion to Daniel Mendelsohn, (I was very much the new kid on the block, having done my first review only in 2007) -- reflected on the Review and on their past contributions to it. I didnt feel I had got much distance on mine, so I decided to look at how Classics in general had fared over the paper's history.

Some of this was quite lighthearted. I played that silly but amusing game of entering key terms into the on-line Review search engine and seeing how often they came up. It turned out that a quartet of leading Romans (Julius Caesar, Augustus, Virgil and Ovid) appeared between them at least once an issue. (I remember Stefan Collini trying this with the online edition of the new DNB -- particularly memorably with the phrase "suffer fools gladly", which it emerged a significant number of those commemorated in the DNB didn't.)

But I was also keen to look at the presence of Classics in the magazine a bit harder. There is an interesting pair of reviews in the current issue, one by Jeremy Waldron reflecting on the continuing importance of classical texts, one by Stephen Greenblatt elegaically predicting the end of our obsession with the Greeks and Romans. But I got most out of the embeddedness of classical references and classical thinking in the very first issue (of which everyone got a free celebratory reprint). This went from a brilliant review by Jonathan Miller of John Updike's The Centaur (he complained about the classical pedantry of the book, and started with the great line: “This is a poor novel irritatingly marred by

good features”) to a whole gamut of classical allusions and comparisons. Susan Sontag, for example, compared our reading of Simone Weil to Alcibiades relationship with Socrates. Robert Lowell told readers that the poet Robert Frost went to sleep with a copy of Catullus on his bedside table.

And I took it back in the end to the basic point I made in the Review last year, that:

"if we were to amputate the classics from the

modern world, it would mean more than closing down some university departments

and consigning Latin grammar to the scrap heap. It would mean bleeding wounds

in the body of Western culture—and a dark future of misunderstanding."

Anyway I was pleased enough with how it went, and pleased too -- lets be practical -- that I left New York before it got snowbounds. Else I really would have had big problems this end.

February 4, 2013

Richard of York gave battle in vain?

Trust me! Just when I have the sympathy of half the nation for being the victim of some vile trolling, I go and throw it away by issuing some curmudgeonly tweets about everybody's favourite skeleton under the car park: namely Richard III. Will I never learn?

Now, actually, the twitter exchange on this one has been good overall, with fierce but polite disagreement. But I still think it might be an idea to explain what I was on about in rather more than 140 characters ...

As it happens, I am in New York and got up early to write the contribution I am to give at a symposium tomorrow. And sure, I was curious to see what the University of Leicester was going to say about their skeleton, so looked on the laptop -- and had quite a lot of qualms about what I saw.

Now there are also loads of good sides to this, as people have been rightly tweeting. If a discovery like this can turn people on to history or archaeology, then that must be a good thing (someone reported the delight of their child at learning that there could be the body of a king under a carpark -- spot on). And I have a frisson, like most people do, at coming face to face with "the real thing/person" (rocking the Roman cradle in "Meet the Romans" was really exciting). Besides, there has obviously been a lot of good archaeology and science going on, which was clearly explained (including the osteology done by someone who had been at my Cambridge college).

So why was I so put off, as well as being intrigued?

Well it wasn't because of Oxbridge sour grapes, as some tweeters alleged, against the University of Leicester .. and I really dont think it was, as someone suggested, a Prof from a Russell Group Uni casting aspersions on a 1994 group university. My first tweet might have made it look like that (if so, I'm sorry), but I honestly dont give a toss what category of uni anyone comes from, and I couldnt even name all the members of the Russell Group anyway. For me, and for most academics I think, it's the work alone that counts -- not what university it's from.

What put me off was a nexus of things to do with funding, university PR, the priority of the media over peer review, and hype... plus the sense that -- intriguing as this was, a nice face to face moment with a dead king -- there wasn't all that much history there, in the sense that I understand it.

Regular readers of this blog will know that I dislike intensely university commercial style marketing -- the posters on campus telling you that the Uni of X is a "global leader"/"in pursuit of excellence"/"making great ideas come true" or whatever. We're universities for heavens sake, not companies -- and we will be judged by our results, not by slogans. The first thing I saw when I looked at my screen was an absolute forest of logos proclaiming "University of Leicester"... getting the brand out there.

Now I am sure that any University would have done the same. We (that's uni's) are so desperate for cash to fund research that we all think that we need to get our name out to attract funding. And there are hundreds of people in uni press offices throughout the land trying to place (and hype) any research story they can to get publicity for the institution. I wouldn't mind if this was really about the dissemination of knowledge, but it's usually not -- it is about column inches. (Indeed I have heard people from uni press offices talk of their success in terms of exactly that, and not minding too much if the account is a bit egged.)

Then I found myself thinking... this is a complicated bit of scientific analysis being given its first outing in a Press Conference, not ever having been through the process of peer review. DNA evidence is tricky and any scientist would want their results peer evaluated before going completely public. OK, I see that there is a tricky dividing line. We want to have us, the public, informed of what's been going on -- and we dont necessarily think it is a great idea that we should all have to wait for that for months or years, until the academic seal of approval has been granted. But the idea of the publication of research by press conference isnt one I feel very comfortable with (as a member of the public, I want not just a story, but a validated story).

Then there is the question of whether media interest starts to set research agendas. This runs through many areas, but especially archaeology. In general, you know that you will get more press attention, and so more funding, if you can link whatever you have found to gladiators or to some glamourous known historical figure (that is why the fine Roman marble head pulled out of the Rhone a few years back was instantly turned into Julius Caesar; there would have been no front page reports otherwise). I'm quite prepared to believe that this skeleton is Richard III (he's where we would have expected him after all) -- but he is part of a climate which pushes people to celebrity history and archaeology, and may even detract from more important work that doesnt have that glitz. (There is an analogue here with medical funding... the sexy areas attract the donations, when what's also really needed is work on dementia, psychiatry and geriatrics).

And then there is the history... Like Neville Morley and Charlotte Higgins, I'm still really wanting to know what history this really adds to our understanding of the period. And like History Matters, I wonder, if it had been the skeleton of some poor peasant whose remains DID overturn a lot of what we though we knew, whether it would have got half the publicity.

This isnt remotely meant to be a plea for going back to the old days when university research stayed in the ivory tower (if I wanted to keep the Romans in the lecture room, I havent been very good at it). It's just plea to "steady on" a bit.

February 3, 2013

What's fun to teach?

It is easy to imagine that university teaching gets more fun, the more advanced are the students that you are teaching . . . third year undergraduates more rewarding than second years, second year undergraduates more rewarding than first year, and postgraduates more rewarding than undergraduates.

Now, I would be the first to claim that it is often truly exciting sitting down with a PhD student who is trying to say something really new, and going through their work, word by word. And it's also huge fun to pick one of your own specialist subjects and to engage third year student in its intricacies too.

But all the same, for me, there is something just as exciting (and in some ways even more difficult) about teaching the first year students. For one thing, you make an even bigger difference to the way they think about the subject. I hope that this isnt the power trip it might sound. But to take students from A level and to push them quickly up to the next (more vertiginous) styles of thinking, and to help them acquire the skills that will enable them to get their own teeth into the subject . . . well that's a pedagogical pleasure that's hard to beat.

This term I am going through Plato's Crito with two small groups of our Part 1a "Intensive Greek" students, in 8 sessions (we have to skip quickly over some of the simplest bits of Socratic dialogue .. the "Am I right, Crito?" "Yes of course you are, Socrates" lines ... to concentrate on the big and difficult passages of argument). Some of the students only started Greek from scratch a few months ago, and the fact that they are reading Plato unadulterated at all at this point is a tribute to their intelligence and hard work, and one must reckon to our teaching too.

I see my job as not only to take them through the Greek ("why is that in the optative?" etc etc) but also to keep them interested in the text. Partly I do that, I confess, by sharing my mixed reactions to the dialogue: on the one hand gob smacked admiration for the sheer cleverness of it all, on the other decided antipathy to the figure of Socrates (and his arguments) as portrayed by Plato. The Crito is, as you probably know, set in 399 BC in the prison in Athens where Socrates is to die, and the question that sparks off the discussion is whether Socrates should try to escape (as his friend Crito advocates, and would clearly be possible) or whether he should sit and face death as sentenced; but this leads on to wider considerations of a citizen's obligation to obey the law.

We see Socrates bulldozing the unfortunate Crito with his usual assassination style of dialogue, and his usual off-putting elitism, which Crito never punctures. "If we are an athlete," Socrates says at one point, "we dont listen to the views of the many about our training, but the views of a specialist trainer; so equally when it comes to morals/ethics and the soul, we should not listen to the views of the many but those of the expert." "Hang on," we want Crito to say, "may be morals are not comparable to athletic training . . . " But the poor man never does.

But what's also fun about this kind of teaching is that each time you read a book carefully with a group of students, you always find something new in it that you've not spotted before. Re-reading Crito this year and last, I've been so struck by Crito's belief that money can always buy you out of trouble. In the first few lines of the dialogue we discover (a bit euphemistically) that the only reason he has been let into Socrates cell so early in the morning is that he's been giving the guard backhanders. And all through the book we find him planning to use his cash to get Socrates out, and worrying about losing it.

Is that really how the wheels of the Athenian democracy were oiled, we wonder.

January 31, 2013

The best of Europe

I have to say that is not without some relief that I have left the country and come to Brussels for a grading meeting for the European Research Council. I know that I have banged on before about how great the ERC is, but this year -- after having just received a good deal of hate mail about the "uselessness" (that's putting it the most politely) of closer links with Europe -- it seemed all the more loaded. The fact is that the ERC is putting vast amounts of money into European research (almost €2 billion in the scheme I am working with at the monent). When you take into account all the other well funded schemes they operate, this makes Europe one of the big players in world research funding, certainly rivalling any governmental strands in the USA. More parochially, the UK gets at least its fair share of that cash -- all sorts of our research, from particle physics to Classics, are heavily dependent on euro-money.

But I am more interested here in the personal side -- because these meetings in Brussels always remind me how much academic life has change for me and most of my university colleagues since we became a bigger part of Europe.

It's not that we were just little Englanders before; far from it. When I was a graduate student I spent several months in Rome (at the excellent British School at Rome), partly meeting Italian scholars and going to Italian lectures (frankly a struggle with the level of Italian I then had, and the speed at which they gabbled). But I would never have predicted then that less than forty years later I would have been sitting round a table in Brussels with a group of other historians from all over Europe, discussing funding applications from an equally multinational crowd of young scholars. The official language of all this, by the way, is English -- but scratch the surface and there's a polyglot Babel going on.

There's nothing like making funding decisions with a group of colleagues to help you get to know them really well. And over the years I've been doing this I've made not only good friends, but some lasting and productive academic connections too. European research really is, in part, now EUROPEAN . . . and not seen in national boxes. And it has been enormously enriched by all this, tedious as some of the eurocrat rules, lets admit it, can occasionally be.

None of this usually comes out in discussions of what we get out of our links with Europe. Now, to be fair, I should concede that the ERC is not technically an EU organisation. It gives money to (and draws on the expertise and contributions of) the "greater European zone", or the "European Research Area"; it isnt just by and for the EU...and it includes not just our old friends Norway and Switzerland, but a wider range of nations (Turkey and Israel, for example). That said, it does feel like an important part of the European project -- and in a wider sense (like the European Court) it is.

Anyway as I toddled back to the hotel last night after a dinner with the panel (not a freebie on the ERC by the way .. but a jolly occasion with plenty of good humoured banter about whether our Greek member's credit card was likely to be accepted by a Belgian restaurant)...I fell to thinking rather ponderously that there was a sort of "two stream" version of European engagement within the UK. There were those who (for whatever reason) came regularly face to face with what we get out of closer European links..and those who may never notice (or be encouraged to notice) those benefits in their daily lives. Maybe its hardly surprising that they dont feel that Europe has much to offer, and noone much bothers to explain.

And that starts at school doesnt it? If so few of our kids are studying foreign languages to any decent level at school, we're not actually equipping them to make the most of what Europe has to offer, or see the point of it.

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4110 followers