Ken Hughes's Blog, page 9

August 25, 2014

How to be a Writer (a modest theory)

Do I really want to be a writer?

(The Unified Writing Field Theory — searchings and findings on what makes stories work)

Everyone who ever glanced at a pen must have asked that, and many of us keep asking. For myself, I think one reason it’s hard to answer is that it keeps leading to other questions to answer first. So I thought I’d try to pin down those questions, and try to find a way through them.

Who is a writer, and who’s a wanna-be?

Sorry, I don’t think this one has a clear answer. Is it when you can talk about writing with your friends? Or when you make your first traditional sale—except then you start needing some bigger success? There’s no one threshold here, but the question points out one thing: we all want writing to have a reward that’s worth the cost.

Can I be a real writer?

Here’s an unpleasant question, because we all have a few doubts. Let’s try to narrow it down some, and look at what those answers say about the writing’s reward and cost:

What’s the best thing to do to be a writer? (And can I do that?)

Feel that? We’re getting warmer now…

–Is it getting my work out there?

Sometimes. If you don’t share, submit, and promote what you write, nobody else is going to pull it out of the bottom drawer for you. But it’s not the key.

–Is it learning to write better?

Some. Feedback, taking classes, or pouring over the best and the worst stories out there can open up whole new worlds for any of us. But, it’s not quite the key…

–Is it writing?

Okay, so the other “answers” were only there for this one to put them in their place. Still, “just write it” is the advice every blogger will give, and it isn’t always enough to motivate us. Could there be anything more to it…

–Is it to KEEP writing?

Yahtzee.

It’s simple truth: every time you write, some of your struggles to make the work better WILL get easier, because there are damn few problems on Earth that can stand up to sheer practice multiplied by days, months, years of building a better mousetrap. (Even though this is one of the few professions where we rarely feel we’ve improved, but that’s another storytelling post: the Scary Bicycle.)

And, bonus: if you mix ongoing effort with some of that promotion above, you build up your body of work, your reputation, even your income. Do it right and all of these only keep growing.

Is there anything I have to write?

This is a tricky one, because it depends on another question:

What’s writing going to give me?

NOT money, or even fame and respect—not if you understand about how little you’ll get, compared to how many years it takes to get there. But if you do it right, the reward you’ll get most of is…

The years you spend writing. Once you find your own balance of sheer fun, or insights to share, or clever craft, or mass appeal, then your playtime (don’t call it work) will drag you to the keyboard every day and make you fight the world for more time to spend in that zone. You’ll still have your slow starts and dry spells, but the writing itself will be as close a friend as you’ll ever have.

What you have to write is, whatever will keep you writing. What will set your work on fire with joy.

(And honestly, if you think being the toast of a convention each month would be worth grinding out three books every year that you hate, you aren’t seeing that effort clearly. Even Stephen King’s royalties can’t make up for the fact that he spends most of his life writing, so he spends that time with the stories he wants. Take a look at Jeff Goin’s Writer’s Manifesto, and take his challenge.)

The writing life never gets far away from putting in those hours. (Okay, and some promotion and learning, I hope.) But it you spend half a day capturing a hero’s way of speaking, working out how to bribe a mayor or describe a dragon’s fire playing over a catapult… doing whatever you want is the only way to make it worth all those hours.

–“Worth”? What I don’t get is why anyone would do anything else!

Writing: there's no escape from playtime.

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

On Google+

Click on pen to

July 21, 2014

Does your villain need more evil?

Is your story good enough?

In fact… you’ve probably been exploring and sweating to make your protagonist more real, more dynamic, and the supporting cast just as compelling as you need. But, could it be that what you aren’t getting the most out of isn’t the good guys, it’s the bad ones?

(The Unified Writing Field Theory — searchings and findings on what makes stories work)

Villains can be frustrating folks to write, with so many of them already out there to make your idea seem unoriginal, if the word itself doesn’t sound cliché to you. Or you might think you’ve got a brilliant villain concept, but wonder if you’re making full use of it.

Well, I know I’m not pushing my villains to the limit, and most other writers aren’t either. But then, I’m not sure villains have a limit.

If “story = conflict,” that can make the opposition a whopping half of the tale’s very nature. The hero’s struggle may be at the center, but the villain is the root of it all, often the one who created the crisis in the first place. Neglect the villain and the hero has more and more moments when he’s struggling against empty air.

A story is no stronger than its hero, or its villain – whichever is weaker.

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

(And let’s face it, a good villain stays with the reader. Heroes need to not be “boring,” but they’ve usually got a relatable balance of issues they’re sorting out over time. But the villain’s liable to make a choice and then “watch the world burn.”)

—Or your writing could be going for a different kind of conflict than Heath Ledger’s Joker. Still, every moment of human conflict can learn a few things from what we call villains. A protagonist still needs major obstacles, whether they’re “bad” people or well-meaning ones; and whatever’s making those people problems ought to be key parts of the story.

All in all, maximizing a #villain is just: write him more like a human being.

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

(Except for tone, most of the time. We’ll get to that.)

How human? Hold onto your keyboard, it’s going to be a bumpy night:

Coming to the Dark Side

None of us want to write someone who’s “just a villain.”

—Okay, some writers do, and it can be downright liberating. But if you do, keep reading: a bit of the same balance can still strengthen them.

But: have you really given your villain enough of a reason for what he does? Could you push him harder? One good measure is K.M. Weiland’s challenge that “Maybe your bad guy is right.” Myself, I think it all comes down to, based on what the reader learns,

“How much would a person like this just NEED to get in the way?” #Villains

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

Of course, “in the way” might mean anything from blowing up the world to a by-the-books teacher who won’t give a student an inch of slack. But whatever they’re creating that conflict about, what these people need is to make that motivation and its ties to the conflict utterly clear. Remember that marvelous Terminator line:

It can’t be bargained with. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop, ever, until you are dead.

If you can give a human antagonist some of that momentum, for human reasons, you magnify everything about the villain. Which magnifies the whole story.

What are those human reasons? You’re probably got your idea there already, so I’ll settle for mentioning my Sith/ Seven Deadly Sins breakdown and my Thunderbolt Ross question as a starting point (is it what he wants to take from the hero, or what he’s afraid the hero will take?).

So what reveals those reasons? It’s usually how well the backstory, the evolving plot, or at least the story’s situation shows this person HAS to do what he’s doing. Possibly the best way is to plot in the way he might be fulfilling his goals without making trouble (bonus points if it’s as a friend of the hero, of course)… and the perfect chance to make that work… and it goes utterly wrong. You also want to choose a balance between the sense of a harsh world that makes that “fall” seem like something that could happen to anyone, and the intensity in this character that shows he’s better than most would be at embracing his fall—if it wasn’t a leap.

Keep asking that question: would this person NEED to get in the way? (The words you’re looking for are “Hell yes!!”)

Darker and Deeper

Once you put the villain on his path… is that enough?

Part of it is “narrowing” that path, finding ways to show that this villain isn’t out to do whatever “bad things” are available, he wants what he wants—meaning, what chances to do damage can he pass up because they aren’t in his interest? The more you show what things he’ll pause for, the less cliché he is and the more you’ve reinforced that the rest is where he will not stop.

(At least, he won’t stop for long. Some of the best villain “falls” happen in the middle of the story, with his missed chances to turn back happening at the height of everything else.)

All this means giving the villain chances to let people live, to clash with his lieutenants, whatever it may be—maybe because it doesn’t fit his plan, or sometimes even because he does have his softer side or other motives as well. It also means surprising the hero (or at least some less villain-savvy friends) with twists where the villain passes up one target to go after another, probably a nastier one. (If you were thinking that The Dark Knight seemed to ignore the last section’s tips about justifying the villain, you’re right. We never learned what made the Joker, but instead the whole movie used this method to demonstrate in detail just what he was.)

To really show things off, try letting the villain do good now and then, maybe allying with the hero if there’s something they both need gone. (“He can’t destroy the world, I need to rule it!” is always fun.) And of course the hero should be spotlighting the villain’s nature too, with every scene where he tries to predict, trick, frighten and generally outwit his enemy. (I’ve analyzed a few ways to do that.)

In fact… could the villain change? Star Wars and many other tales turned out to be about redeeming their villain. Or he could give up his evil world-view for a different and even more vicious one. (In its most overused form, “If I can’t have her…”)

Villains may be implacable at the right moments, but they need a sense of precision and even change as well. Because they aren’t forces of nature, each is something much more terrifying: a human being who’s actively looking for ways to get you.

Note that word, “actively.” That’s the next question for maximizing a villain: are the hero—or you—taking them for granted?

Continued next week.

On Google+

Click on pen to

July 14, 2014

The Prologue Checklist

“What’s past is prologue.”

–William Shakespeare, The Tempest

It’s only natural—you’ve got a powerful story to write, so you open with a prologue. It’s your chance to show off a clever idea, it guarantees the tale has a wider scope and maybe an extra viewpoint, and it’s traditional for everything from Lord of the Rings to every other horror movie made. Shakespeare used plenty.

Then you hear it: “I don’t read prologues.”

(The Unified Writing Field Theory — searchings and findings on what makes stories work)

We can hear it from some readers, from bloggers, from agents that sound like they’re willing to slam the door on our best idea and maybe the whole story too. When I started hearing that, it’s hard to say which of my reactions was louder: “D’oh!” or just “That’s not fair…”

Yes, a lot of writers love prologues, and readers too. That might well be the cause of the Prologue Problem: for every marvelous example of the art, it’s easy to find case after case that doesn’t exactly push the writing envelope. And I admit, much as I relish their potential, more than once I’ve felt my eyes moving to skimming speed when I come across the P word.

It’s just too easy, to find ourselves writing a prologue without asking the hard questions it needs. My own latest, The High Road, has seen its prologue go through more than one total rewrite. But, I’m thinking the process comes down to:

#1: Is the prologue idea just a way to ease into writing this story?

Prologues are as natural as “Once upon a time,” especially if we’re still getting a handle on what the story is. Just start with a big picture or a contrasting part, and work our way over to the focus, right? Trouble is, “pre-focused” is exactly what the first pages of a story can’t afford to be.

How often do you revise your first chapter, and your first paragraph, knowing the whole story can be judged by how perfect those are? I’m betting it’s more than a few times—in fact, many authors decide their actual Chapter One was a distraction and they’re better starting the story on Two.

First-Scene paradox: the one bit you NEED to work is what you wrote as you learned the story.

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

So ask yourself, could this prologue idea have already done its job, by helping you find some better scenes? Keep this in mind as you ask the next questions. (And if it doesn’t make the cut, “outtake prologues” are prime candidates for a Bonus Scenes section of your author website, so no scene has to be truly abandoned. DVD-makers figured that one out years ago.)

#2: Do you have the PERFECT contrast with the rest of the story?

This is the big one.

The one defining thing that makes a prologue different from a regular chapter is how it isolates part of the story from the rest: a character giving history, a young glimpse of the hero, something. And normally storytelling is about how much each part is integrated with the rest of the tale—so are you sure the best place for this thing is right out there in front, on its own?

Maybe the clearest prologue I know is in Pixar’s Finding Nemo (thanks to Feo Takahari for pointing that out). The bulk of the movie is Marlin struggling to, well, find his lost son, but it’s also him facing his own overprotective ways. And the fastest, clearest, most irresistible way to set that up was to open with a tragedy that gives him a reason to be so worried—and not just setting it on the day the rest of the story begins, but long before then. As a prologue.

Or: horror tales love prologues. Any time the story wants to follow an ordinary person slowly discovering the nastiness, but the writer still wants to make an early promise that the payoff will be worth it, an easy choice is to open with a glimpse of the monster. And a victim, of course.

Fear vs finding confidence. Full-on villain vs slowly-alerted hero. See the key here?

A prologue that really pulls its weight zeroes in on the perfect element to contrast with the rest of the story. If that contrast is so vital that it itself should be the first thing you show your reader… so essential that it would be a distraction to give that one thing a full-sized chapter or too smooth a flow on to the next thing… if you’re sure of those, you’ve got a prologue.

Use a #prologue only if it's the perfect thing to play off the rest of the story, and no more.

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

(If not… If it’s only a good piece of contrast but not a perfect one, it’s better off worked into a regular Chapter One or elsewhere. Or if you really want a sense of history or scale first, you could open with a snippet from a history book, news report, or letter, but not call it a prologue—in fact, you could weave bits of these into the start of every chapter instead of putting them in one place.)

One other thing: if any point is so vital the reader can’t appreciate the story without it, put it in Chapter One as well. If the prologue’s good enough, we can afford to be generous even to the prologue-haters.

#3: Size matters

Readers expect prologues to be small. You might have a marvelous concept for one built like a midsized chapter, but it’s hard to convince the reader you’ve got true laserlike precision that leads right on to a strong chapter when the prologue itself wears the reader out.

No, there are no rules about size, but I’ve heard “500 words” mentioned as a good high average. That seems about right; it should mean (at least with print paperbacks) that once the reader turns the page once she won’t have that dread moment of “Two more pages aren’t enough? Is this prologue out of control?” In fact, if you can hone a prologue down to two pages, or one, you can impress the reader even more.

To put it another way, a prologue is no place for just a slice of life. It might have a strong point combined with a slice of life, but you want to make it a thin slice.

(No, you don’t want to do a prologue for flash fiction. The second season of Arrow doesn’t count.)

#4: Are you giving the prologue what it deserves?

A good first scene can easily make your story; a weak one can certainly sink it. It’s no secret that you want any opening to be the best it can. Prologues have the same need, plus the added burden of convincing reluctant prologue-readers… and they have the sheer power of having such a focused goal.

So if you can make the prologue the best scene you’ve ever written, the rest of the story will thank you. Dig through your whole arsenal of writing tricks, from imagery to irony to a really unique point about the scene’s character, and how you could twist the plot up, down, and sideways just for the sake of showing off.

–And then don’t do all of them! You want to use your best writing judgment too, about the ideal central technique for what the prologue needs and how many more tricks can fit in around it without overstuffing it. (Well, without quite overstuffing it. Like any story’s opening, you still want to blow the reader away.)

Extra tip: if the prologue isn’t about the hero’s younger days or about the villain (and these may be the two best reasons for a prologue), consider killing off its viewpoint character right then. That saves the reader from wondering when he’ll show up again. It does also add to the risk that the reader will decide you’re abandoning the story’s best material, but a good prologue needs to invest the reader in what’s coming rather than just itself. Besides, you can think of a memorable prologue character as a challenge to be positive your hero’s even better.

Maybe the best single advice I’ve heard for this comes from another movie: City Slickers. Granted, Jack Palance as Curly the cowboy was talking about how he simplified his whole life, and that’s more than most of us want to use his rule for, but it’s perfect for prologues:

“You know what the secret of life is? One thing. Just one thing. You stick to that and the rest don’t mean shit.”

And the real secret the movie claims is that we all have to find our own One Thing.

(Image credit: Sundayeducation.com)

A prologue works… if you have the right One Thing to make it about, and you keep everything else out of the way, and you make that thing worthy of the spotlight you’ve given it. (Okay, for a prologue it might be fairer to say it’s “one contrast” between two elements there, like a character and just who betrays him, and how that combination then contrasts with the rest of the story.) But if you don’t have that one clean combination—if you can’t sum it up in one sentence—your story’s better off with a full-sized Chapter One.

It’s a hard choice. Every character in a story (and ones that aren’t in it yet) has their arguments for being the prologue viewpoint, and prologues may still feel like the likely way to work your way into the story. But, is this idea the One Contrast that the reader needs as a prologue, or not?

If it is, you’ve won yourself a rare insight into what makes your story tick. An opportunity like that would be a shame to waste.

Now excuse me here. My own book’s start needs some more trimming… and I’ve got some prologue cynics I’m hoping to blow away.

“And, by that destiny, to perform an act,

Whereof what’s past is prologue, what to come

In yours and my discharge.”

–William Shakespeare, The Tempest (the real quote, emphasis mine)

On Google+

Click on pen to

July 7, 2014

Deals, Decoys, and Dirty Tricks for your Characters

Your hero’s trapped by his enemies, no way to run or fight—unless he can take what those goons really want and use it against them. Your villain needs to slip past the police lines to work his sinister plan, but how? Or even, what would it take to make those two stop and call a truce? It all comes down to knowing who you’re dealing with.

(The Unified Writing Field Theory — searchings and findings on what makes stories work)

It’s the classic question, used by Mr. Morden to tempt the people of Babylon 5 and by cops to talk down hostage-takers: “What do you want?” Because once you know a little about what makes a character tick, you have four easy ways another character might use that to influence them… and better yet, deepen the story by revealing how well they and you understand them. Win/win.

The framework I use comes from comparing what we’ll call someone’s “Standard” action—let’s say searching a smuggler or attacking a hero—with the “Offer” of doing what our trickster wants instead. The options for making that Deal work come from either giving the Offer a better reward, or reducing the Standard’s reward. Or it might happen in negative form, where instead of changing the balance of the two “carrots” you change the “sticks:” reduce the Offer’s cost for taking it, or raise the Cost of staying with the Standard.

–Yes, the last is the classic “Offer you can’t refuse.” Or,

4 ways to manipulate a character: hire him, get him fired, reassure him, or threaten him....

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

Survivors and Smugglers – some samples

How does this breakdown work? Let’s take two scenarios: a smuggler trying to get goods past customs and a zombie-hunter who needs to keep a particularly large wave of undead away from a camp of refugees.

Offer’s reward: This might be the simplest, and because it delves into people’s motivations directly it may add the most character depth to the story.

The zombie concept makes it simpler yet: just what draws them to attack people, and what part of that could be used to draw them away? Will a loud enough noise draw them from a distance? Or does it have to be about getting in close, running just ahead of them, and not heading into some (yes I’ll say it) dead end.

The smuggler eying the customs officer can get into more human territory. It means something if that guard is less interested in policing the border than in some extra cash—and is it for himself or his sick child? Or if he’s so shaken by a developing war he wants guns smuggled to those rebels.

On the other hand, even if the guard only cares about stopping crime, that could make him willing to trade for tips about a much bigger smuggling ring. Or just faking (or exposing) another smuggler nearby would make the perfect distraction, just as fresh meat can lead zombies around. Best of all might be if that smuggler can pose as an undercover cop.

Standard’s reward (reduced): This plot twist may actually take the most work to pull off, but it does dig pretty deep into characters and their lives.

Zombies don’t give many options here. You’d need a way to make the refugees less appetizing, compared to the decoy; most worlds’ zombies being the tireless eating machines that they are, simply hiding the victims might be the closest thing that counted.

But the smuggler might get past a guard who’d given up on his work. If he can find the most burned-out inspector in the place, or even make that inspector lose his faith that anyone will listen to him, the inspector has no reason to put much effort into searching our smuggler.

(Or for a more thorough example, picture the army that bypasses the Impenetrable Fortress to take the capital beyond it. Even if the fort is vital in its own right, its defenders may have nothing left to fight for.)

Offer’s cost (reduced): This is usually in the mix with other tricks and deals, part of tipping the balance the way you want.

For decoying zombies, it might mean keeping the bait from getting too far ahead or crossing any ground that’s hostile enough to zombies to make them turn back. If these zombies are afraid of fire, don’t go near burning buildings until you’ve finished drawing them away.

For the smuggler, it’s recognizing what bothers the guard about letting him through. Probably that he’ll get caught and expose them both, so the smuggler has to seem competent enough that the Offer is less of a risk. But it might not be that: if the guard has lost friends to gunfights and the smuggler switches from running booze to running Uzis, that smuggler may be in for a nasty surprise.

Standard’s cost: This is the other simple tactic—really the simplest of all, since almost anything’s easier to harm than create. That means it might be a last-ditch toolset of quick and dirty options that say more about the situation than the character you’re leaning on… or they might show just as much insight as the best Rewards do. Plus, they might create the most conflict of all, since someone using them tends to make lasting enemies.

For zombies, it could be as simple as throwing up a wall of fire or some barriers to climb over, between them and the refugee camp. It won’t stop the horde, but it might be just enough to encourage them to go after the decoy instead.

The smuggler… You can probably guess: threats, ranging from exposing how much the guard’s already collaborated with him to targeting whatever the guard cares about.

Then again, sometimes the “stick” that character needs is already part of the situation, if you make the right part of it clear enough. If our smuggler is also sneaking children out of a ruthless dictatorship, and the guard takes a good look at them, the balance can shift on its own. (“It’s not a threat, it’s a warning, about who you’re working with…”)

That’s how I break down my options, when I have a character in a corner—or need someone to put him there—and want a plot twist that isn’t just brute strength. If I can outbid (or undermine) the Standard reward one character was relying on, I can make a strong statement about what was driving him; reducing the Offer’s cost keeps the plot twist on track; adding or finding costs in the Standard is another approach that might clarify character or might bypass it.

Something else you can see in these examples are that sometimes a tool works by changing one side of someone’s choice with the right offer or threat or other efforts, sometimes it’s deception (faking that same kind of change, or hiding one part of what’s in the balance), or else revealing the whole picture. If you look at my four Plot Device articles, you’ll see these are all ways to use Strength (or Movement) and/or Knowledge to affect a choice between two Motives.

It’s all about that pair of options you give that character, and the “What do you want?” or don’t want that lets you tip either side of that scale. Once you learn to look for those options, you can turn your characters loose to trick, bully, seduce… and even find grounds to make friends.

On Google+

Click on pen to

June 30, 2014

The Plot-Device Machine – Motive

A story is its people. We all know that, and that’s why Motive is different from the other Plot Device points. We’ve seen how Movement and especially Knowledge can organize the plot around the Strengths that will determine just who gets what they want… but Motive is what they want. And it doesn’t matter if the rest of the story is about fighting Dracula or diabetes; it’s plotting from the characters’ Motive that really brings it to life.

(The Unified Writing Field Theory — searchings and findings on what makes stories work)

What counts as Motive? I’d say,

Motive is what characters want or don't, or some belief that "filters" their choice....

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

In its simplest, it’s what goal someone could go after in the story. Fight or flight. The patriot’s war, the money-grubber’s deal, or the mother’s child. Family, love and friends, work, and coping with other problems are the common starting points (I’ve got a post on those options). And it isn’t only action stories that tend to make it “negative” rather than “positive,” on the grounds that saving a planet or a relationship (or at least rebuilding one) can make a more intense story than building it the first time. That’s just how we humans are wired, to react to threats faster than we notice opportunities.

Or Motive could shade into attitudes, expectations, or patterns that aren’t strictly “get this/ stop that” goals. This could be filters over charactrers’ actual goals, but one that’s just as key to what the people are and how we can use them: the company man who just won’t see what his firm is really doing, or the giver who’ll stick her neck out for anyone. Anything that affects the choices they make.

Why is Motive juicier than the other pieces of the story? I like to think it’s so fundamental it really is the part that the reader’s own life can share in. We just don’t connect a tale’s spotting a murder weapon lying in the corner (or even a time-saving accounting trick) to our own struggles, not the way we watch Peter “Bannon” in Hook missing his son’s proverbial baseball game and think of the choices we make every day. And it isn’t about kids, or any match between story subject and reader (though we all know it doesn’t hurt!), since so much of our lives are always dealing with other people. We don’t need to meet an alcoholic—or a vampire—to let a character with a secret remind us everyone has their private demons.

Human nature; in the end we’re all fighting the same battles. I think that’s why stories work....

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

But… every writer talks about character and motive. Don’t I already have enough of that in my story?

Moments for Motive

One way to make full use of Motive is to check scenes, character layers and their conflict (for all characters), and larger contrasts. For instance:

Which scenes really hinge on Motive rather than Strength, Knowledge, or Movement? Star Wars might be crammed with shootouts and chases, but the loudest cheer in the theater always comes when Han and the Falcon drop in to clear out the Death Star’s trench after all.

How many Motives does a character have? “Depth” is a word we like to throw around, but can you count how many goals and beliefs each of your cast has that make a difference? We can tell a minor character by only having two or three… but if a side character has more Motive issues than the hero does it just might mean you’re telling the wrong person’s story.

How much do those Motives clash? Indiana Jones doesn’t slow down often to show off his issues, but he lets the Nazis (the frickin’ Nazis!) get a chance at the Ark’s ultimate power because he’s too much of a scholar to blow it up.

Still, build-up beats bigger stakes. For every story worth remembering, we’ve all seen way too many that announced everything was life or death, but didn’t take the time to establish why we should care. Has Michael Bay ever seen The Blair Witch Project, let alone read A Christmas Carol?

How many characters have layered Motives, complete with all the above? Even building the story around a multilayered hero shouldn’t hide the chance to make other characters the key to some some scenes, and to build up just how hard a choice they have to make. In fact…

What patterns do characters’ Motives form? This might be as simple as giving hero and villain opposite drives—or as careful as making the villain all too similar (the famous “Shadow Self”) to spotlight that one defining difference. It at least ought to mean sheer variety in the cast; what’s the point in giving the hero two friends if they’re both driven by revenge?

Answer: to show how two very different people can have that Motive in common. Or how two “similar” folks can become different.

Some of the best-designed stories out there can come from combinations of which characters seem similar but have a different Motive, or seem different but turn out to have something in common. Lord of the Rings gives us Boromir’s desire to save his people, that opens him to the Ring’s influence… and his brother facing the same choice and resisting. Meanwhile Frodo sees Gollum is actually another hobbit driven by the same hunger for the Ring that he’s coping with himself, until he can pity his enemy and make him an ally—and all the back-and-forth twists that that leads to, to make us wonder how far either of them can be trusted with this kind of power around. Or how much poor Sam will put up with.

If you want a theme, compare two characters with their motives. Or six, and their changes....

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

To me, that’s what writing is. It’s a chance to explore what kind of character has what in common with who else, or how different they can be—and then how the story can change those to show more truths underneath those. My Paul Schuman thought if he could stay away from his family he might have some kind of normal life again; Lorraine will fight for a complete life beside Paul’s brother, but still not tell Greg what she’s become part of. Mark Petrie wants to keep Angie Dennard and her father safe, but by getting them away from danger, not using the magic Angie wants to master, while Joe Dennard has his own reasons for avoiding it. Contrast, of Motives.

Well, the story’s that and pinning those Motives to the Strengths those people need to work for (and against) them, and spreading the storylines out with the evolving Knowledge of how they and the reader can only see so far, and the Movement that some of their “steps” to it mean they never know what might happen when they pass the next dark alley.

But it’s all there.

On Google+

Click on pen to

June 23, 2014

The Plot-Device Machine – Strength

Welcome to the whole story… or at least a chance to step back from looking at single aspects of writing, like the last two Plot-Device posts did. Now that we’ve explored how characters’ movement and knowledge keep changing how the story works—and the ways each ends up reshaping the tale—it’s time to look at a third aspect and see how they all fit together to build a story. I call this third quarter of the Plot Device, Strength.

(The Unified Writing Field Theory — searchings and findings on what makes stories work)

(“Strength? What if my story only has a bit of fighting in it?” comes the voice from the back row.)

I’ll admit it, I’ve never had a perfect name for this one. That’s because it takes in every component in the story world that doesn’t fall into the other three groups.

“Strength” could be any tool or resource characters use to make a change in the story, and whatever’s in the story that gives them that opening. A hammer can break down a door, or nails can put it back up—or it could be someone having the muscle to smash that door, or how fast someone’s tiring from the room being on fire, or the fact that there’s a door there to smash and not just another stretch of wall. It does usually means physical “things,” but there’s also room for some abstract power in the grouping; if our hero’s goal is to write an unforgettable song, “strength” might be inspiration, time to work on it, and probably years of study or experience so he’s ready to write.

But the reason I group all these together is to tease out the other Plot Device aspects separate from them, and let them work in the ways we covered in the other posts. Our musician may test out and “learn” which chords work for his song, but that still works better as working through the songwriting’s Strength on its own terms. Meanwhile if part of the process is hearing one musical style and remembering it’s the way he always wanted to sing, that might open up things like:

Since he only has to hear that sound again once, it’s Knowledge—and like we’ve seen, it can have a whole investigation to track it down, or a theme-friendly depth of learning what kind of musician he’d rather be.

If he has to go to a hundred clubs before he hears it, that’s Movement’s way of spreading the story out, and giving him a chance to stumble into friends and enemies on the way.

Or there’s Motive—but that’s for the next post. Combining these two with Strengths is fun enough.

Finding Strength factors can be trickier than it looks, with so much weighing into it. My rule of thumb is:

Everything characters deal with is a lock; some just have keys that are harder to get....

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

The “locks”: look on all sides for what makes anything a weak link, or ready to change. Small-scale example: look left and right and all through the building for where there might be a door someone can try to open. (Are there windows? Or are the doors so reinforced it’s easier to smash the wall?)

Don’t forget, what’s changing on its own: from tides coming in and batteries dimming, to politics changing as whole generations fade away. Or, what times are they just not there (or some rare thing is) and that changes the mix?

The “keys”: what tools, resources, skills, possible allies, and so on are out there that can change one of those—enable it, fix it, whatever you need?

Yes, those keys might need components to build them, or bargaining chips to get someone involved, that break a simple process down into more scenes. We’ve all seen stories plotted like that, but they make sense if you don’t take them for granted.

Plan B, C… You’ll always come up with a few locks and keys that might work, and some that would have worked if the conditions weren’t forbidding them, and probably a few that sound beyond crazy. Any of those are good for that moment when our hero shows he’s trying to think of everything—or of course if you have any time for Things To Go Wrong.

The other guys, and forces. Remember to check all the above for how every other character (like the villain) is busy looking for their own shot at their own goals, and how all characters have changes around them even if nobody’s taking advantage of them. The hero has to sleep too, and if our villain knows where…

Strong enough? Once those Strengths start to come together, you can write two ways: You can run a fight, surgery, or any other scene with the classic suspense of whether they’ll actually win. Or you can keep all the tension on the plot twists just before that, on just who’ll get the right tool or enemy attack there in time. (But then, I like to have the outcome hanging on skill and then keep changing the rules…)

Again, this the purely Strength side of it. You might have the perfect “key” that our hero just doesn’t Know about, or can’t Move out to get. Because it’s that combination, taking those Strength points and pacing them out with Knowledge and Movement (and all the smaller cycles within those) that really starts to look like a story. In fact it starts to look like a treasure map, but one that does justice to the complications you’d have trying to follow it.

The Treasure Map of Oz

Time to see how these work together. In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy’s goal is simple: getting home. The Strength to do that turns out to be in her magic shoes (silver or ruby, depending on your choice of media) and her love of family to make them work. But that’s the Plan B, since there’s also the Wizard—

(There’s that back-row voice again: “Her goal is getting home? Doesn’t that make all of this Movement?” Well yes, it could be called that, but that’s a move she doesn’t start until the story’s end. The tale’s Movement parts aren’t the flight to Kansas and whatever happens on the way, they’re her journey to find Strengths that could let her go.)

So Dorothy’s quest is to discover the depth of love (Strength) to work those shoes… after she stops relying on the Strength of the Wizard. In fact the Wizard’s offering two ways out: a perfectly good balloon ride (that turns out to be too time-sensitive for a girl with a dog-shaped Deus Ex Machina), and before that his “magic” that’s a red herring—a bit of Knowledge plotting. But first, just to learn about that “Strength” she has to go and claim another Strength, by beating the Witch.

And those several Strengths are scattered over Oz—imagine how much shorter the tale would be if the Wizard and Witch were right there when she landed with the Munchkins, ready to fight out their differences with her in one busy scene! Instead it’s that Movement (and the missing Knowledge about the Wizard) that spreads the story out on the way to those Strengths; it’s what gives her time to meet her three friends, dodge the Witch’s attacks (our villain doesn’t miss her chances to use own Strength), and of course build up the Strength she’ll really need. And all those journeys, discoveries, and fights are made up of their own combinations of these—the Tin Woodsman even gets to break down a door.

Other stories are their own mix of the same elements. A thriller might turn on getting hold of a bloody shirt for evidence, layered over with the trail of Knowledge to find it, the Movement to get to each clue, and the Strength to reach them and come out alive. A business story could be gathering the resources to launch that billion-dollar idea; a monster hunt needs get hold of its silver bullets and then track down and shoot the werewolf.

(“But that isn’t ALL the story! Why is Dorothy even chased by the Witch, why’d the Wizard send her after her, why are her friends and her home so important—”)

I know. That’s the last piece of the Plot Device puzzle. Strength may give us pieces that Knowledge and Movement lay out, but we all know the thing that really aligns them all, and makes the story mean something. So next week: Motive.

On Google+

Click on pen to

June 16, 2014

The Plot-Device Machine – Knowledge

“You can run but you can’t hide.” It’s simple truth, that getting distance from a problem may be no match for how “Knowledge is power.” And that’s only one side to how who knows what defines the story: you might move your characters around in your story to control how the plot unfolds, but knowledge almost is the plot.

(The Unified Writing Field Theory — searchings and findings on what makes stories work)

Think about it: Knowledge is the only other side of the story that actually matches how our reader’s experiencing it. Unless it’s a travel guide, they aren’t following those movements; unless it’s a how-to they won’t be assembling the characters’ kind of strengths.

But knowledge means something, if the story can make us wonder “what’s really going on there” and let us share in the answer… because that answer or how to search for it always says at least a bit about our own lives. It could be

Specific: Bilbo solving each of Gollum’s riddles. Each time we figure one out ourselves, we cheer; each time we don’t, we sweat just a little for him.

Game-changing: the Green Goblin learning Spider-Man’s identity. (It’s not just what the hero knows!)

Layered: how much of a romance comes down to pacing what moments the couple are “getting to know” the chemistry they have, matched against False Impressions?

Or, bedrock: under all their clues, mysteries can get their ultimate power from revealing just how vicious a killer was right next to us all along.

So the more of your story is tied to the revelations in it, the harder it can hit.

Knowing when to Know

It may be because information’s about blind spots, but I’ve seen (and committed) so many moments where a plot misses one side of holding its mysteries together. A story can’t lose track of:

What’s someone know, right now? What does that make him think he needs to look into next—or not care about at all, so far?

And, how does his assumptions play into it? There’s no better tool for a character arc than to find the facts he just won’t accept, then show how wrong he is.

Then, how many ways can he follow that up? Talk to people, bring up Google, or track down a Dusty Tome? Run a test in a lab?

One trick is to consider all five senses (or more, depending on your cast!) for what signs each fact might leave, including from its history. Detectives look for everything from footprints to strange sounds to glimpses in ATM cameras, and all the associates and back-story a suspect has. Can someone really run away from an enemy without coming back all sweaty?

Also, which of those signs can he use best, to follow up? A hacker might dig through a dozen servers before he knocks on a witness’s door, but Sherlock Holmes will spot everything from calloused fingers to unscrupulous accounting at a glance—and he’ll know what the combination means, and how to poke around in disguise to get the next piece.

Check what all characters know, not just the main ones. Look at each step your central characters take (in investigating and everything else), and ask who else is going to get a hint of that and start nosing around themselves—or just jump right in—and what that tells the hero to look into, and keep things escalating. There’s just no comparison between Lois Lane being fooled by Clark Kent’s glasses and the thrill of Indy hauling up the Ark only to discover that the Nazis were watching him digging…

And, what are all those players doing for “information control”? Can they keep from leaving those traces (tiptoe past those guards), or erase them later or explain them away?

Better yet, who can trick who with all of that? There’s the “moment of distraction” that could tweak any moment in the story… and then there’s Holmes’s defining trick of pretending to set fire to a house, to make the blackmailer herself reveal her hiding place. And of course some of the best plot twists come when the villain (or hero) realize they’ve been tricked and the tables start turning.

You can lay most parts of the story out in terms of how each scrap of knowledge lets the hero—and everyone else—move forward, or else move off-track with your red herrings.

In fact, in many styles of writing, most of the pages are simply the combination of searching and moving. Whether it’s a grand investigation, sneaking around an enemy, or just describing scenery (whether or not real clues are hidden in it), they form the same pattern:

Typical scene: everyone moves in their most informative direction, sees what’s there, rinse and repeat.

Think about it, how many ways are there that really vary from that? There’s when someone settles in to search in one place (through a process like reading or talking), or into a flat-out race or chase where speed matters more than scenery (but even then, things can come up in the environment to help them maneuver). There are Strength moments, from fights to change-the-tires scenes, that I’ll get to in the next Plot Device post. And you have other conversations, that can be their own mix of Knowledge and Motive, and maybe some Movement (or Strength) too. But mixing Movement and Knowledge might be the bread and butter of getting things written.

In fact, part of the balance is how much you’ll let Knowledge obsolete Movement. Do characters need to go out to look at a site, or just run tests in their lab—or even skip gathering the lab samples if they can just talk to someone who’s seen it happen? (“Where’s my flying car? It’s called the Internet.”) Which means you can choose what clues call for legwork, and which dead ends aren’t shown on the map, to pick which discoveries get more emphasis… or just more chances for complications.

And of course, the more amazing a character’s control of knowledge is, the more it reshapes the whole story from the start. (If you’ve ever played a video game with a secondary “radar display” to keep track of your enemies, you know how different it feels to see a bit further!) Many a story’s been built just around why the protagonist knows at least a little that the rest of us don’t: the psychic, the spy, or just the witness nobody believes. Or it could be the same advantage in reverse, being the invisible man or inside source that can hide in plain sight. Then you have the challenge of building the story around just how much more they can find and what limits they still have.

(No, Superman, the missile control doesn’t have to be inside the lead box, that’s only the first thing where you can’t see what’s inside… oops.)

Knowledge, and movement, can be the major tools for organizing a story. But the other two Plot Device tools… those are the story pieces themselves.

On Google+

Click on pen to

June 9, 2014

The Plot-Device Machine – Movement

I’m about to share with you my all-purpose tool for the all-purpose question that my characters (and I’d bet yours) are constantly asking. That question is, “How do I get out of this one?”

(The Unified Writing Field Theory — searchings and findings on what makes stories work)

Or, it can be how the hero will find a new way into a dilemma that holds the key he needs, or of course how enemies and good old Murphy’s Law can get at him. From escaping traps to staying on the good side of a tempestuous ally, in a hero’s eyes his life is a multilayered challenge that almost seems to be conspiring to push him to his limits.

And readers never stop asking the same questions, because they know his life is!

So much of the nuts and bolts of writing is building the dramatic out of the practical. Would that escape be more intense if he bargained rather than fought his way through? Does the plot touch all the bases of tracking a killer?

When I’m looking for problems or solutions for my characters, I’ve found I have four main options. As a writer you won’t see any of these as new, but I think the key is in seeing the combination of choices, and the ways they can steer a scene or story. (Plus, me being me, they all have their own implications for picking someone’s paranormal or other suspense resources.)

So my plot devices are either about:

Movement

Knowledge

Strength

Motive

Movement

Yes, I listed movement first, and it’s not because I have a weakness for chase scenes. Stop a moment and think:

How many pages are the hero working his way through a place? Movement matters....

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

On a small scale, mobility can mean chase speeds and barriers, or whether hero or villain can find an unprotected approach to get where he wants. (Try the back door, crawl up the sewers, whatever way’s the weakest link.) On a larger scale, running a business or just getting through the day have their own logistics issues, and a problem anywhere on all those roads—or getting a new and better way around—may well be the most changeable part of the story. Or, you can force the heroine’s boyfriend or mentor to move across the country, even if it’s just to make phone contact less comfortable.

As often as not, part of making a whole scene or more story work is physically placing everything it needs. That can mean having a sense of:

Pacing—of the story, not the people on the move. Do you want to stretch a scene out with escape maneuvers, or sum up a month of military campaigning with a paragraph that explains thinning supply routes? Giving a section more space usually means finding more complications for it, and a longer or rougher ride is an easy way to provide that.

Or else, just taking movement out of a scene focuses it on everything else. The more you’re trapped with your enemy, for better or worse, the more you know something’s about to change… though even then something might come between you…

Who wants to bring which things together, and who doesn’t? Is that bystander who sees the approaching figure a cop who thinks standing and shooting at a monster will do any good, or is it Carrie Coed who’s perfectly happy to RUN AWAY?

Speeds, and also distance, to which goals. Letting Carrie run to just “get away” may not be as intense as having her run to her car. So how far from the parking lot is she? How near was the beastie to catching her—and if it moves at a nice suspenseful shamble, the only way to let it gain on her may be to say poor Carrie’s already limping from a previous chase.

But then, movement isn’t only raw speed. If Carrie had one of my own books’ flying belts to float up out of reach (assuming the monster didn’t too!), or she had to run around a chain fence while the monster oozed right through it, the chase may take a very different turn.

The big one: check everything for how it can change. Cliché or not, it’s only human for Carrie to stop and stare when the monster pours through the parking lot fence, or maybe even drop the car keys she needed. (Yes, this can be more a chance for “shock,” mixed in with more straight suspense of just following the movement.)

Especially, focus on how those characters try to control those. The creature might be smart enough to see that Carrie needs to run to the lot exit now, and try to head her off. But if Carrie had actually dropped her backup keys, and then doubled back to her car with her real ones, she can get to drive straight through the thing—SPLAT.

(Good for you, Carrie!)

All in all, movement ought to be a natural part of working out any writing. Wherever the story physically is, distance and barriers are a big part of stretching it out (distance metaphors—we can’t get away from them). And you’ll always find a few aspects of it that can be perfect for twisting the plot.

Especially, it can be part of defining the characters, and the story as a whole. A mobile hero might be the perfect match for a stronger but slower enemy (no wonder Peter Pan can laugh at all those pirates), or a faster, elusive villain can make him the one frustrated. At the same time it can set the scale for the story: Carrie only has to drive across campus to find out why her friends aren’t answering their phones, but the further Clark Kent realized he could fly, the more of the planet Superman patrolled.

If you don’t think movement can reimagine a whole story, two words: Road trip!...

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

With all the different pieces of your plot, movement can be just the way to control who gets to act on what.

That is, if they know about it. Which brings us to next week: Knowledge.

On Google+

Click on pen to

June 2, 2014

Worth Fighting For – choosing stakes for characters

When I’m first putting my sense of a story together, there’s one question that can turn the different pieces into a whole, sometimes faster than any other choice I make. And that is: what does a character want?

(The Unified Writing Field Theory — searchings and findings on what makes stories work)

I don’t mean the deep study of how the world looks through his eyes, not yet. (And not the “What’s my motivation?” acting jokes—although any cliché like that was usually washed downstream from a good idea up somewhere.) No, I mean a simple decision about what part of the story keeps that person in the action, in terms of his own history.

Think about how you come up with a concept, and what ideas come to you first. You might start with a protagonist and build the world as you start to understand her; “What kind of person would try to hide her psychic powers to live an ordinary life?” Or you might begin with a sense of the conflict (“wizards at war!” or the cause at the root of it, or just a setting you want to draw a story out of. So many ways we can go.

or the cause at the root of it, or just a setting you want to draw a story out of. So many ways we can go.

But to keep those pieces from pulling apart, we want at least a basic sense of which of them got our people involved. In some stories this may be less important than how the plot escalates (such as trying to stay alive), but even as a starting point it’s a good one. So I like to look for whether the character’s here for:

Family: The earliest, maybe deepest motive we all have. When Inigo Montoya says “You killed my father, prepare to die!” or a troubled teenager tries to keep her sister from following in her footsteps, we all know how much is going on. It’s especially good for bringing in the weight of the character’s past; half the story’s subtext may be her fighting for these few people to not see her as who she used to be.

Love and Friends: If family’s bound up with the past, these can start as casual and in-the-moment as Watson’s initial curiosity about Holmes—or as life-changing as Romeo catching a glimpse of his enemies’ daughter. It might be the most versatile motive of all because that other person could be anyone, with whatever bond to the character you want to build up, and they have all their own ways of changing and pulling people in deeper.

Work: The classic, if you want the story tied to how police work or ranching operates, or at least how Certain Events are complicating those. Harry Potter starts his adventure wanting to earn his place as a wizard, and the sheer weirdness of Hogwarts fills half the pages of the books. And like Harry shows, this choice can be all about the structure that job brings, but it can also be an easy string for pulling in characters you don’t want to give a separate supporting cast to—or to show off how someone like Harry doesn’t have any good people in his life, at first.

Accident and Entropy: Sometimes a killer just thinks your hairstyle is more fascinating than the others on the street—or you win a lottery, or wake up with a disease. The other stakes usually come with their own baggage, but here we can say “It had to happen to someone”… and then build the story from how that plays off the rest of the character. That random target becomes all about whether her ordinariness (and all the unique bits it came from) will help her survive; the lottery winner finds out what he really wants in life. If you want this kind of setup, you’ll usually know it.

Whatever else the story does, the better I know a character wants the right thing, the more the whole story hangs together. The High Road starts with a family secret, but making my viewpoint character Mark a friend of the Dennards keeps him a step back from their legacy to appreciate it a bit more. It spotlights his relationship to them but told me I had to show how specific his reasons for being there were, from his suspicion of the magic he’d glimpsed to his lack of a stable family himself.

Besides choosing a type of stake, here are three other things that choice can lead to:

Often the way the character sees that goal can be as distinctive as the thing itself. If you look at the Marvel movies, Thor and Iron Man both start their arcs as superstars who think they know everything about changing the world, while the future Captain America is a weakling who dreams of making a difference any way he can. One person might have lost someone and be driven by revenge or just stumbling around with a grudge against the world, but a different spin on the same concept can give you a character trying to make amends—either to the people he’s failed or to the different ones that are all he has left.

Or, the most impressive thing about stakes may be the combination of them, and how many you cover or contrast. Harry Potter comes to Hogwarts to train, but he also has his lost family to discover, and the friends he soon makes… and even touching all those bases makes any character more complete. Or look at the symmetry between Harry and the picture we form of young Voldemort: both Hogwarts students, both from nightmarish homes, but Harry’s honest friendships (and how easily he makes them) make it easy to see how different their lives will be. Just think of a classic mystery: half the story might come out of “the real killer did it for simple greed, while the red herrings have these flashy love and cover-up-the-accident motives.” Or how many stories are about changing a character from career-chasing to love or family.

Most of all, choosing someone’s goal ought to be a signpost to what to flesh out next. “For his father” is pure cliché if it just lies there pretending to be a complete answer, without detailing what that father’s like. Other characters may never mention their parents at all, but that only works for the ones that have whole different forces driving them. And the better you are at picking which of those basics each character depends on, the sooner you can fill in what they’ll mean for the story.

Besides, the heroine’s father might turn out to be the hero’s too, if you find you’re creating the next Darth Vader…

On Google+

Click on pen to

May 26, 2014

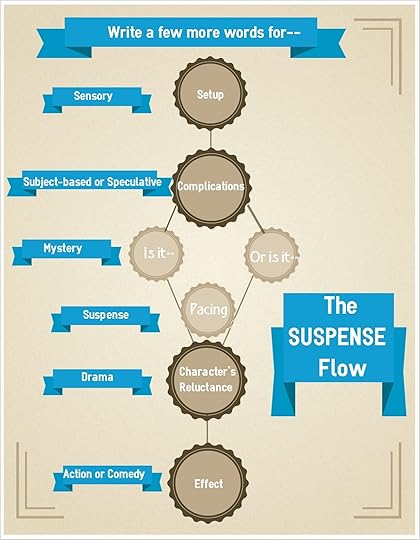

How All Writing is Suspense

Why is my writing all about suspense? I think a better question is, is there any story that isn’t really about building uncertainty, making the reader wonder about what comes next, making them care? Suspense. And understanding that may be the perfect tool for any kind of writing.

But suspense is only one genre, isn’t it? One Wikipedia page (since it’s probably the quickest source to go check; I’ll wait) lists 22 genres, and umpteen variations within them. I actually class my own writing as fantasy, urban fantasy and paranormal in particular, one of several genres that many people think of for its distinctive character types and weaponry (see also Science Fiction) or conflict (Crime or Mystery).

Except, many of those genres are about choosing tools. When a writer sits down to use them, Tom Clancy doesn’t have the same aims as Ian Fleming, and my battles aren’t trying to imitate Seanan McGuire’s. (Not that anyone could…)

What the idea of suspense can do is bring all genres and styles together—and show how each of us is making our own writing choices, even line by line, but all following the same cycle.

I call it a “suspense” flow, because I think that’s the word that captures the energy we want each part of a story to have—especially how it depends on balancing different parts of the flow to get the pacing right. You might argue for “action,” “mystery,” or other words, but I think “suspense” captures more in one word. And it all builds on what all writers do know is: conflict.

If #conflict is the "engine" of a story, the #suspense flow shows which "gear" the engine's in....

Click To Tweet - Powered By CoSchedule

How does that help us writing?

Partly, we can use the suspense model for a larger view of what any part of a story needs, whether it’s a single passage or a five-book plan. Such as checking for:

someone to root for

tone or atmosphere

complications, and a sense that these would be what he has to deal with

choices that are hard enough to reveal the character

pacing, not rushing or bogging down on the way to—

an outcome that means something

All of these are basic elements of writing and conflict, but this fits them all together to see them as part of the same cycle—and to ask whether they’re building the right kind of momentum, involvement, suspense.

“But my writing’s barely about suspense!” –If that’s what you’ve been thinking, consider this: the suspense flow is more than a way to find common needs in the genres and styles. It’s also a way to look at any part of writing, and to pick if you have any particular priorities for it:

If you want sensory mood or detail, you can start painting the picture right from the beginning, even before things happen.

To make your story more about its subject (anything from a neighborhood-specific tale to a political tale to SF and fantasy), you might define more of it by just what complications come out of it. Be sure the reader knows why it’s those problems those people have to face, and what that means.

A sense of mystery can mean playing up the contrast between choices about the subject, and of course stretching out how long it takaes to find that answer. Was it the vampire or the best friend that dunnit? Just why was the ruined city abandoned?

Or, classic suspense in its own right means extending the whole process, whether it’s building up more mood or looking for further complications to keep things up in the air.

Pure “drama” usually is code for making characters more important than what happens—not just important (we all want that), but focused on how they resist or interpret or put their own slant on the facts. Even in a whole sprawling war, nobody’s going to have the same PTSD as this one soldier.

Or an action story needs to do justice to the effect itself, the explosions at the end of the suspense cycle before the cycle starts up again.

(For that matter, comedy has the same need to stop there and enjoy the laughter. That same moment of release might well have explosions too, as long as fewer people are getting hurt.)

Naturally each point on the suspense flow is only as good as how the rest of the flow meshes with it. Only the crudest action story gets careless about why the danger’s there, or the hero’s choices in facing it; sensory description that shuts off once the complications appear would be absurd. And again, “suspense” is a reminder that it only works when the pieces have the right balance for the pacing we want.

Even a sequence that’s all mood or description can look at this pattern. By the time that boy finishes strolling out to the lake, what state of mind should the passage have nudged him to, and the reader with him? Do the bits of detail contrast with each other in ways that stir up preferences in us (looking at the open sky, and the gritty, tiring dust his feet kick up, before he’s finally rounding the corner), or give a sense of one thing disrupting another to demand our attention?

Can you look at these and see which part of the flow you want to give a bit more justification, a few more words, or an extra scene?

It’s all there, by one name or another. And if the combination of your words catches fire, it will do it partly because of what we call suspense.

On Google+

Click on pen to