Nancy I. Sanders's Blog, page 58

June 13, 2014

The Writing Desk of Gretchen Griffith

My writer’s desk is in a room I call my study, but actually is the room my son left vacant when he left for college several years ago. There is a fouton in it for the grandchildren when they come over, but normally it is as covered over with clutter as my desk.

At this spot I have written numerous manuscripts, many of which are in the bottom drawer of the filing cabinet never to be seen again, chalked up to learning experiences. In addition to the picture book and freelance articles in newspapers and magazines, I have published three narrative nonfictions in the memoir genre.

Connect with children’s writer Gretchen Griffith!

Learn more about her books and her life as a children’s writer at these sites:

Website: Gretchen Griffith: Storycatcher/Author

Blog: Catch of the Day

Facebook: Gretchen Griffith Author Page

Twitter: @GretchenGriffth (note I had to drop the second i in my name that was already taken)

You can also connect with Gretchen on Pinterest and Google+

_____________________________________________________________________

CLICK HERE if you’re a children’s writer and would like to see your writing desk featured here on my blog!

June 12, 2014

Self-Editing Tips: Which Genre Is It?

As we’re working our way through the NONFICTION PICTURE BOOK SELF-EDITING CHECKLIST (available by CLICKING HERE) I wanted to talk about checking our manuscripts for the use of “Creative Nonfiction Techniques.”

First on the list is the question, “Is every statement, every dialog quote, and every detail 100% true?”

If not, you have choices. You can choose to keep in the non-true stuff and your manuscript will be classified more as “fictionalized nonfiction” (nearly, mostly true) or even “historical fiction” (a made-up tale about true people or events).

Or, you can choose to delete the non-true ingredients and keep your manuscript in the nonfiction genre.

I discovered that I was adding in a bit of fiction, so I took all that out and kept it in the nonfiction genre. HOWEVER, I did opt to include some “legend” as part of the story. So I’m making a note to myself to discuss this with an editor if it reaches that stage to see what the publisher might think about dealing with this.

The important thing as you’re checking this is not whether you’re writing pure straight nonfiction or not, but just be sure you know which genre your finished manuscript falls into and that you’re happy with this decision.

June 9, 2014

Self-Editing Tips: The End

Today let’s take a look at the ending you wrote for your nonfiction picture book.

But before we examine the end, let’s look back at the beginning.

How did you start your picture book?

With a question? With a bold statement? With an inspirational introduction? In the middle of a high-action scene?

One very satisfying way to wrap up a picture book is to end it in a similar way you began.

For example:

If you started with a question, bring up the question again and in a brief recap, show how it was answered.

Your beginning:

Did you know blue whales are the largest mammals on planet earth?

Your ending:

So how big is a blue whale? They’re the biggest mammals of all!

If you started with a bold statement, tie your ending back to that same bold statement.

Your beginning:

Frederick Douglass was the Dr. Martin Luther King of the Civil War era.

Your ending:

Frederick Douglass paved the way in his generation for Dr. King and the American Civil Rights Movement.

Using this technique to tie your ending back into your beginning leaves your reader with a high level of satisfaction as he turns to the last page of your book.

June 6, 2014

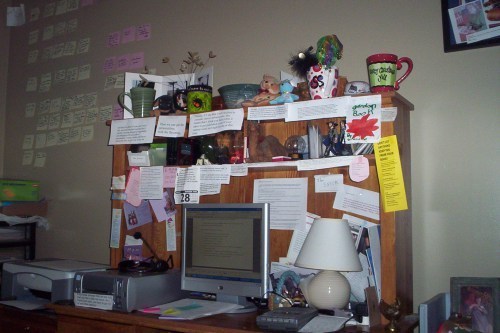

The Writing Desk of Pat Miller

Here is my desk. I am in mid-project, working on a nonfiction book about Stephen F. Austin and his cousin. The state of my desk, messy but loosely organized, reflects the state of my research at this point. Before I start writing the draft, I will clean off my desk. That’s in keeping with my mental state when I switch from harvesting facts to producing what I hope will be engaging nonfiction.

Connect with children’s writer Pat Miller!

Learn more about her books and her life as a children’s writer at these sites:

Website: Pat Miller: Reading…Writing…Fun!

Nonfiction Writer’s Conference: NF 4 NF: Children’s Writer’s Conference: Nonfiction for New Folks

_____________________________________________________________________

CLICK HERE if you’re a children’s writer and would like to see your writing desk featured here on my blog!

June 4, 2014

Writing Workshop: Getting in the Zone

I hope you can join me next week on Wednesday, June 11 at 2:00 Pacific Standard Time as I teach a workshop on how you can get in the writing zone to produce the quality and quantity of writing you want.

CLICK HERE to visit the Working Writer’s Club and sign up! (Even if you can’t join me live on the telephone, you can get the audio replay later.)

I know this is an issue we all struggle with, so I’m sharing solid strategies I use that have worked for me over the years.

Hope to connect with you and GET IN THE ZONE!!!!

June 2, 2014

Self-Editing Tips: The Middle

One more note about self-editing the content of your middle:

As you work to write details, descriptions, and anecdotes in your middle that support your main idea or develop your main story problem, plan to include those that are most important or carry the strongest weight. If you’re struggling to decide which to include and which to cut, an exercise that helps me is to step away from writing for a moment. Talk with people (especially kids!) about your main idea instead.

Call a friend and say, “Hey, I’ve been reading the most interesting things about William Penn. Remember him? He’s the guy who started Pennsylvania. Did you know…?”

As you talk with various people about your topic, make a mental note of which details keep rising to the surface like cream in a gallon of whole milk. Listen to yourself and note what you’re passionate about sharing. Make a mental note of which details your listeners are eager to hear more about. These are the details you want to include in your manuscript’s middle and develop into anecdotes and scenes. Just be sure to present them in a way so that they work to support or develop your main story problem or main idea.

May 29, 2014

Self-Editing Tips: Middle

Authors and writing instructors often refer to the middle of a manuscript as the “muddy middle.” Details can get messy here and scenes start to resemble your grandmother’s knitting basket with loose tails of yarn hanging out from skeins jumbled up together until it all looks like a great big knot. I prefer to think of the middle of a manuscript, however, as the “marvelous middle.” Remember back to your childhood of fingerpaints and playdough and imaginative play and marvelous, wonderful sunshiny days of carefree fun. The middle of our manuscript is the place we get to explore and create and investigate and build the world of our characters and ideas. You can learn the skills it takes to write a successful middle, having fun during this process instead of being overwhelmed with it all.

When you write a manuscript built on the Three-Act Structure, it will have a distinct beginning, separate middle (with two parts), and definitive end. The middle is the place where you include details, descriptions, and anecdotes that support and develop your main story problem (as in most fiction) or main idea (as in most nonfiction).

Just a note however, if you are writing a manuscript such as a picture book that uses a predictable plot rather than the Three-Act Structure. In a picture book that has a predictable plot such as an alphabet book or counting book, your middle should follow the pattern you established in the beginning. (For more information about predictable plots, read page 238 in my how-to book for children’s writers, Yes! You Can Learn How to Write Beginning Readers and Chapter Books.)

The approach to take to develop a strong middle when your book is built on the Three-Act Structure is similar to the way we keep our own middles trim and firm: avoid the extra carbs. If we’re trying to tone our tummies, we avoid or cut out empty calories from our diet such as potato chips or soda pop. We do tummy trimming exercises that firm our abs.

It’s the same with writing. We want to avoid or cut out any details, descriptions, or anecdotes that don’t support our main idea or develop our main story problem.

In a chapter book or novel, this helps keep our story from wandering off down aimless bunny trails. In a picture book, this task is even more critical. That’s because with an 800-word count that many editors prefer in today’s market, we simply do not have the luxury of wasting a single word.

When we’re dieting, we want to shop and choose healthy foods such as whole grains, lots of leafy green vegetables, and fresh fruits. Likewise, as we’re writing the middle in our manuscript, we want to brainstorm and choose details, descriptions, and anecdotes that strongly support our main idea or work in a meaningful way to develop our main story problem.

In a chapter book, middle grade novel, or young adult novel, we have the luxury of crafting anecdotes and scenes fleshed out with pages of dialogue, description, emotion, and action. Some scenes even progress through one or more entire chapters! In a picture book, however, each word we choose and each scene we create in our middle will be deep in meaning and short on word count. Picture book writers have to learn to create anecdotes or scenes sometimes in a single sentence or single paragraph because the art fleshes out the rest of the scene. Or course, there are longer anecdotes and scenes in picture books, but many times these are created with a minimum of words.

To help you learn how to write details, descriptions, and anecdotes in your manuscript’s middle for the genre and market you’re writing in, study how your mentor text handles these. Following is an example, however, for you to see the difference between writing an anecdote or scene in a chapter book or novel versus creating the same anecdote or scene in just one sentence in a picture book:

Chapter Book or Children’s Novel

(Scene in a story about William Penn and his father)

The Delaware chief Tamanend sat in the center of the wilderness clearing at the river’s edge. The leaders of his tribe sat behind him in a half circle like that of a waning crescent moon. Behind them stood too many natives for William Penn to count.

William Penn stepped forward to the side of Chief Tamanend. Penn’s small group of Quaker friends gathered behind him. The chief held in his hand what William Penn thought looked like a wide belt decorated with sea shells.

“This is wampum,” an interpreter explained who was sitting among the tribal leaders. “It is highly prized and worth much value to our people.”

Tamanend held out the wampum in a gesture of trust and friendship.

Bowing slightly, William Penn reached out to take the wampum. “I am highly honored,” he said. “I accept this payment in the name of King Charles II of England.”

Penn gestured with his hand in a wide circle that included the clearing, the trees, the river behind them, and the sky. “I will start my new colony here,” he said, pausing for the interpreter to share his words with the chief. “Pennsylvania will be a settlement where personal liberties and religious freedoms of all men will be honored.”

William Penn saw the shadow of a smile flicker across the stern face of Chief Tamanend as the interpreter finished speaking. That shadow reminded Penn of the last time he had talked with his father before the aging gentleman had died.

With an unexpected ache he couldn’t quite describe, Penn wondered what his father would have thought if he had been here to witness this scene.

Picture Book

(Same scene in a story about William Penn and his father)

As he took the wampum belt from the Delaware chief Tamanend in exchange for the land where he planned to establish his new colony, William Penn wondered what his father would have thought had he been here to see this.

Of course, in the nonfiction picture books we’re writing, we keep everything true to facts. But as you’re going through the self-editing process now and following the Nonfiction Picture Book Self-Editing Checklist, evaluate the content of your manuscript and focus on your middle to be sure you included interesting details, descriptions, and anecdotes that support your main idea or story problem.

May 23, 2014

Self-Editing Tips: Beginning

As we’re working to edit our nonfiction picture book manuscripts, let’s talk about the main story problem.

Establishing the main story problem in the beginning of your story provides the tension a story needs. It lays the foundation for every scene to be built upon. It gives your MC a goal to work toward through the entire duration of your story. Plus, it engages your reader (and editor!) and compels him to read the entire rest of your story to discover how our MC solved the main story problem at the end.

Stories that do not establish the main story problem in the beginning lack sufficient tension and consequently tend to ramble. Without the main story problem in place, scenes lack purpose. Your MC appears to be wandering down bunny trails or chasing a wild goose. Readers feel uninterested in the MC and have a hard time connecting with the story. They have a vague sense that they’re watching a series of unrelated events and will put aside the book for something more engaging.

In the beginning of our nonfiction picture book, as authors we therefore have three basic options:

Option #1: Establish the main story problem.

Option #2: Hint at the main story problem.

Option #3: Lay the foundation to establish the main story problem later on in the beginning.

For example, let’s pretend our picture book is about an ostrich named Olivia. The main story problem is that someone has stolen Olivia’s ostrich egg from her nest.

Here is an example of how we could establish the main story problem on the very first page of our picture book as in Option #1:

“Where is my egg?” Olivia cried. “Somebody stole my egg!” (We know someone has stolen her egg.)

Here is an example of how we could hint at the main story problem on the very first page of our picture book as in Option #2:

Olivia took a long drink from the river, then headed back to her nest. She wanted to double check that her egg was safe and sound. (We wonder if something has happened to her egg.)

Here is an example of how on the first page of our picture book, we could lay the foundation to establish the main story problem later on in the Beginning, or Act 1, as in Option #3:

Olivia was quite forgetful. Every morning she forgot to brush her beak after breakfast. On chilly fall days she forgot to wear her warm scarf. And she always forgot whether she should look left or right—or both ways—before she crossed the road. (We know nothing yet about Olivia’s missing egg. But we know she is forgetful, which establishes the foundation for the main story problem when in an upcoming scene we learn she is so forgetful, she forgot to keep watch over her egg and somebody stole it.)

These are fiction examples, but the same holds true for nonfiction especially when you are writing a biography, an historic event, or using creative nonfiction where you’re incorporating fiction techniques to convey the information to your reader.

So look carefully at the beginning of your manuscript. Did you establish the main problem (or idea) in the beginning?

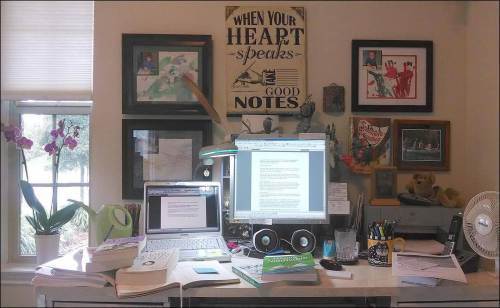

The Writing Desk of Nancy I. Sanders

When I write, I like to move all over the house. I typically spend mornings at my desk in my office where I type in the manuscript I’ve been working on by hand or type in research notes to back up my facts.

I like to spread out as I write and often set up a 6-foot cardtable in my library where I can spread out my research notes and research books and piles of mentor texts I’m studying…right next to my current sewing projects!

I often sit in a comfy chair to read research books and take handwritten notes. It’s here you’ll find me sitting to read my manuscripts aloud to my cats, too, who are always willing to listen and give feedback…not!

And most afternoons (and evenings when my teacher husband Jeff is nearby grading papers or reading a book), I’ve got my feet up on our comfy couch…snuggled up with my writing buddies of course!

Connect with children’s writer Nancy I Sanders.

Learn more about her books and her life as a children’s writer at these sites:

Website: www.nancyisanders.com

Blog: Blogzone

Facebook: nancyisanders

Facebook Author’s Page: NancyI.SandersAuthorPage

Twitter: @nancyisanders

Pinterest: nancyisanders

Stumbled Upon: nancyisanders

And if you’re a children’s writer and you’d like to be featured on this site, too, I’d love to have you join in the fun. Here’s what to do:

1. E-mail me at jeffandnancys@gmail.com

2. E-mail me at least one jpg photo of you at your writing desk. You can send me more if you write in different spots throughout your day.

3. Include in your e-mail a note about your life as a children’s writer. It can be as long or as short as you like.

4. Include any links to child-friendly sites such as your website or blog. Also include your links to Facebook, Twitter or social media sites you’d like me to post.

5. Then wait a week or so. I’ll e-mail you back when your link is up and running!

May 20, 2014

Self-Editing Tips: Beginning

Today and in upcoming posts, we’re going to be talking about practical steps we can take to edit our nonfiction picture book manuscripts.

We’ll be using my Nonfiction Picture Book Self-Editing Checklist. You can find it on the site of my writing buddies, Writing According to Humphrey and Friends. Just scroll down until you find the link to click on, then download the free pdf file to print out and use.

Let’s start at the top by talking about CONTENT.

Does your beginning introduce your main character?

The first page of most published picture books has three key ingredients. It introduces the main character, establishes the setting, and establishes or hints at the main story problem. As you’re working on the first word, the first sentence, the first paragraph, or the first couple of paragraphs in your manuscript that start your picture book’s beginning, you want to include these three key ingredients as well. However, it’s important to remember that you don’t have to incorporate all three ingredients into your text. The cover, the title, and the art will all be there to work together with your text in the final, published book.

Main Character

With this in mind, let’s focus on introducing your main character on the first page of your picture book. We’ll start with your character’s name. Unless you are writing a story where it is important that your main character remains nameless, you want to introduce your main character by name to your readers right at the start. Introduce your MC’s name either in the title or in the opening text of your manuscript, or both.

Perhaps you’re working on a picture book that focuses on an event rather than a character. In stories such as these, you might want to introduce your main character later in the text. For most picture books, however, especially with biographical nonfiction, it strengthens your story if you introduce your main character to your reader at the very beginning.

If your picture book doesn’t have a main character but is about a topic such as dump trucks, be sure you introduce your topic right at the beginning of your manuscript. Again, this can either be in the title or the first page or both.

Most main characters in a picture book, even in nonfiction, have strong, unique character traits. Try to introduce at least one of these key traits right at the start. If it doesn’t work in the text, be sure it’s included in your working title or in potential art.

If in the art, write art suggestions in [brackets] such as [Art suggestion: Main character is wearing a pirate’s eye patch.] If it’s in the working title, however, just remember a word of caution. Working titles are often changed by the publisher, so be aware of this through the publication process. If somewhere your original title gets dumped, you’ll need to be careful that the essential ingredients your working title contained make it onto your published first page.

Nancy I. Sanders's Blog

- Nancy I. Sanders's profile

- 76 followers