Graham Storrs's Blog, page 17

September 18, 2011

I'm Featured Today on The Book Blather Blog

Courtesy of the very kind Marilee Brothers, I had the chance to blather about the three-ring circus we call publishing on her most excellent blog. If you're interested in what I think about small publishers, self-publishing, and the Big Six, you should hop over there. If not, you should go there anyway as there is a wealth of fascinating posts by far more knowledgeable and interesting people, all on your favourite subject*.

—

*Books and publishing, of course. What did you think I meant?

Why You Can't Even Give Your Books Away

I came across a tweet today. It was from a complete stranger, about a book I'd never heard of. This is the full text:

I came across a tweet today. It was from a complete stranger, about a book I'd never heard of. This is the full text:

"Whassamatter with you guys? 127 minutes to go and the offer for a FREE Kindle copy of [Book Title] closes! Tick tock…"

Reading between the characters (tweets are so short you don't get the luxury of lines) here is an author trying to promote his book who thought it would be a good idea to give it away free for a period to get some interest going. It seems like a reasonable thing to do and yet, you can tell he isn't having a lot of luck with it. The puzzlement is obvious; surely people will grab a copy of your book if it's free? After all, it's free! Free, as in, it doesn't cost you a penny. There is also, I suspect, a hint of fear there too. If you can't give your book away for free, what do you have to do to get people to read it?

The problem is that the premise is all wrong. A book – any book – is never free, even if you don't have to pay for it. It will still cost you hours of your time to read it. And your time is without doubt the most precious thing you own. It's a finite resource, you have very little of it to spare, and there are a million other things you could be spending it on.

So let me make this post uncharacteristically short and jump straight to the take-home message. If you want people to read your book, you have to persuade them that it is worth their time to do so. Sell it to them. Get them to want it. Convince them that the hours they spend reading it will be much more fun and fulfilling than spending those same hours in any other way, and on any other book. Then you won't need to give it away – or sell it for $0.99c. An experience that good is worth paying real money for.

August 31, 2011

TimeSplash the Audiobook is Available Now

Well, it was a long and strange journey, but my time travel thriller, TimeSplash, is now available as an audio book – thanks to my newest publisher, Iambik Audiobooks. So, as we speak, TimeSplash is on sale as a self-published ebook and as a commercially published audio book, and it is in production at eMergent Publishing to appear soon in a print edition. Talk about a hybrid publishing model! Iambik has the audiobook rights, eMergent (almost, almost) has the print rights, and I have the ebook rights. (And, if a big-budget film producer would like to make my day, I have not yet disposed of the film or merchandising rights. So drop me a line, OK?)

But let's talk about that audio book for a minute. I first published TimeSplash as an ebook with a publisher called Lyrical Press. Which is how my friend Emma Newman got to read a copy. She and I had become pals via our blogs. She was agonising over whether to self-publish her novel 'Twenty Years Later" at the time and I was just agonising. Emma started podcasting her novel, reading it one chapter at a time and putting it up on her blog. She had a surprising reaction. Not only did people like her book (which was not surprising at all) they loved the way she read it. I mean, really loved it. These podcasts changed Emma's life in all kinds of ways. Firstly, she built a large following, and, when she started Twittering, that grew even larger. Then she signed a three book publishing deal for "Twenty Years Later" and two sequels (so no more agonising – she'd made it!) . Then she started looking for work as a voice artist, recording other people's books – and has been finding it.

As a side venture, Emma started recording my novel, TimeSplash, suggesting that she jointly self-publish it with me. I was flattered and very keen on the idea, so we worked on it for several months. Which is to say, Emma worked, I simply listened to the chapters as they emerged and said, "Wow! Cool!" and so on. By the time it was over, Emma had made contact with a publisher who wanted her to read some of his books. She let him hear some of TimeSplash and he wanted that too. This was an outfit called Big Bad Media, based in Denmark. Not long after I signed contracts with them for a print and audiobook edition of TimeSplash, they went out of business. It was a bit of a shambles and looking like a complete flop until eMergent Publishing (based just up the road in Brisbane, of all places) said they were interested in the print rights that BBM had forfeited (yay, eMergent!).

And that was an outcome I was reasonably happy with. The downside was that all Emma's work on TimeSplash might go to waste. And that would have been a terrible thing. Her reading of the book has a strange effect on the story, you see. When I read it – when most people read it from the text – it seems as if there are two protagonists, Jay and Sandra. This young man and woman are caught up in the events of the story and whirled along. They sort of fall in love as they hunt down the timesplashers and fight their personal demons. But, when I wrote it, it was mostly about Sandra and her terrible struggle against fear and her crushed self-esteem. And the miracle was, when you hear it read by a woman, by Emma, suddenly it's clear as day that this is Sandra's story above all else. So I really wanted Emma's telling of this tale to survive.

That's why, when she made contact with Iambik Audiobooks as part of her ongoing rise to stardom as a voice artist, and she sold them the idea of publishing TimeSplash, I was over the moon. That was almost exactly five months ago and my head is still reeling from the surprise and delight of it all. The path from the first idea for the story (in May 2008) to this day, with the audio book sitting on the shelf at Iambik, has been long and tortuous and filled with kind and talented people like Emma who have pushed and promoted TimeSplash with incredible generosity (and ultimate success!)

What can I say but "Thank you", to Lyrical Press, to Greg McQueen at BBM, to Jodi Cleghorn and Paul Anderson at eMergent, and to Gesine Kernchen and the team at Iambik, and, especially, to Emma Newman, for keeping this sometimes sputtering flame alive for so long? I could not have done it without you.

And that's my very talented daughter's artwork on the front!

August 20, 2011

The Strange Geography of eBook Sales

Before I go on, let me just squee* for a moment. The second edition of my time travel thriller, TimeSplash, is out today (on Smashwords - out tomorrow on Amazon), It has had a bit of an overhaul, too: new cover, slight re-edit, and two new ISBNs. That's it, on the left of this post. The blue one. Feel free to stroke and pet it.

The audiobook and print editions are out soon too (from proper publishers) but the ebook (2nd edition) belongs to me. I'm also squeeing because I successfully steered the MS through the increasingly rigorous requirements of Smashwords and Amazon to end up with a book in both the major ebook markets of our time: The Amazon Kindle Store and The Rest.

Pricing was interesting. This was the first time I got to set the price for TimeSplash. Before now, my publisher had set the price at $5.50. Now the responsibility is mine and I had to think long and hard about it. In theory, the cheaper an ebook is, the more you will sell – but the less you will make on each sale. But that is only if you believe ebooks are price sensitive. I know that Joe Konrath says they are (and has evidence to back that up) but my own experience is that there is an area, somewhere under $10 where it really doesn't make much difference. Free is very different, and I have discovered that you can shift ten times as many books in a week as you can in a year if you're giving them away, but let's not go mad. I have a starving Airedale to feed. So I decided to peg my book to the price of a cup of coffee at my favourite coffee shop – which is $4.50 for a large cappuccino – which is what I always order. That seems to me to be about the right price/value point for a full-length novel in ebook format.

And, finally, to the point about geographies. I've never used Amazon to sell ebooks before and I had heard they take 30% of the sale price of a book, leaving 70% to the author. This isn't actually true. They take 30% in some countries (eight or ten, maybe) but in the rest, they take 65%, leaving just 35% for the author. As it happens, one of the countries outside their 30% zone is Australia – where I live, and where I might expect to make the most sales**. Does anyone have any idea why this is? The whole formula for determining price on Amazon is so baroque you would need a lawyer to help you understand it, but it's easy to see that they're trying to fix the market so that they don't get undercut. Yet this different royalties in different geographies thing has me totally confused. What is that all about?

And your take-home messages? Self-publishing is possible but all publishing is weird. And you can buy TimeSplash at Smashwords for exactly the price of a cup of coffee.

——————-

*Squee v. The rare emission of joyous noises by authors, who may have waited many years to make them.

**In fact, I make most sales in the US and the UK, and almost none in Australia. Possibly because Australians don't like science fiction (as an Australian publisher said recently) and they don't like ebooks (talk about late adopters!)

August 3, 2011

Yasmin needs brain surgery but can't afford it

It is a sad and terrible indictment of the society in which we live that a woman like Yasmin McKillop might die because she can't afford the surgery that could save her life. Yasmin is a young woman, a nurse who cares for old people at my local hospital. She's one of those lovely people you take to immediately. She is married to my friend James, who is blind, and they have two young boys. And now, Yasmin has a brain tumour. The prognosis from surgeons at the public hospitals here is very poor, but there is a surgeon in Sydney who believes he can save her, if she can find sixty thousand dollars for the operation.

On a nurse's wage and James' invalidity benefits, Yasmin has no house to sell, no savings to draw on. Her family are just ordinary, working people. That kind of money is so far beyond the reach of normal people that it must seem completely hopeless to her family and friends.

In desperation, her sister, Mia, has launched an appeal. Mia is not a media-savvy campaigner with far-reaching networks into the circles where money like this is easily found. She's just a young woman who lives and works in a small, country town who loves her sister and is doing all she can for her. She has put up a Facebook page. She is talking to local people and local businesses – in Stanthorpe, one of the poorest towns in the whole of Australia. That's why we need to do something to help Mia raise that money and save her sister.

I know most of the people who read my blog are writers and working people too. I doubt we could raise that much money between us, but we can raise some, and there are plenty of other ways we can help. This is what I would like each of you to do.

1. Visit Mia's Facebook page and donate something to the appeal – even if it is only $5 – the price of a cup of coffee. The link is also at the bottom of this post.

2. Use the +1 and the Retweet buttons at the top of this post to spread the word to your social networks. You can also Digg the post, or use StumbleUpon or any other sharing tools you like. Do whatever you can to help Mia get the message out to the world that Yasmin needs help.

3. Mention the appeal on Facebook, LinkedIn, Google+, MySpace, Twitter, and anywhere else you have an audience.

4. Write a blog post on your own blog – even if it is just one sentence with a link to Mia's appeal page, it might just help.

5. If you know a journalist, mention Yasmin's plight to them. A 'human interest' story like this might just be something they, or a colleague, are looking for. If the story made it into a State or national newspaper, or was mentioned on a popular radio or TV show, it would take the appeal to a level where anything is possible. Even if you don't live in Australia, mention it anyway. Generosity doesn't stop at national borders.

6. Write a letter and send it to your local newspaper, your local radio station, your local Rotary Club, anywhere you can think of where people might be willing to help.

I'm sorry to ask. I'm sorry to live in a society where I have to ask. Please help Yasmin and her family. Please do whatever you can.

The link to the appeal is http://www.facebook.com/Yasmin.Aid?sk=info

July 23, 2011

Writing Novels Is Hard, But I Enjoy The Struggle

I'm 24,000 words into my new novel and I can't help thinking about the process I'm going through as I hammer this story out, word by word.

Novels take a long time to write. Well, they take me a long time. Some people bang out several in a year. I'm happy if I can write just one. The last novel I finished was a sci-fi comedy called Cargo Cult. From beginning to end, it took me more than ten years. Even when it just takes a year, it's far too long to plot it in detail and then just write what you plotted. In a year of living with a group of characters in your head and a particular set of ideas you want to explore, you are going to find that things develop. Your initial plot can seem shallow and weak by the time that year is up, same with your initial characterisations, and your initial thoughts on your main themes. I'd go so far as to say that, if these things don't develop, mature, improve, deepen, and evolve while you write the book, you're just not thinking very hard about what you're doing.

Day-to-day, of course, nothing much happens. The actual mechanics, the craft, of putting words on screens is absorbing and takes up most of my resources. The choosing of every word, the structuring of every clause and sentence, the building of every paragraph, section, and chapter, are all such massive tasks with so many possible alternatives, that it is a miracle a mere human brain can do the job at all. Probably it can't. Sometimes I find myself 'satisficing' (as the brilliant Herbert Simon once put it) when I'd rather be optimising, but I'm limited by what my brain can do. I suspect the mark of genius in writing is the degree to which optimisation is possible for an individual writer.

The majority of thinking about the story, its characters and ideas, for me at least, goes on outside the periods of actual writing. I just don't have the capacity to do both well at the same time. Sometimes the need to understand some element of the story is a prerequisite to proceeding. I become lost in a miasma of ignorance and stupidity as I grapple with some important idea without which the story cannot proceed. Sometimes this is a technical issue – how long the tether needs to be for a Lunar space elevator, for example, or how the Polish secret service processes interviewees – and these are the easy ones. They can usually be solved with a half-hour of research (and some maths revision). Much harder are questions of how a character should develop – what's realistic, what's likely, and what's best going to serve the story? Or what the future will be like. I spent several days doing nothing but charting likely developments in science, politics, economics, society, healthcare, various technologies, etc., and their tangled interactions, over the next fifty years, before I could write my novel TimeSplash. And then did it all again, pushing it out an extra thirty years for The Credulity Nexus.

The hardest problems of all are the ones to do with concepts. For my novel Time and Tyde, I spent scores of hours reading books and papers on the physics of time travel (none of which appeared in the book, but I needed to get it straight in my mind before I could be confident I wasn't going to write something stupid). For Emissaries, the first book of my first "Omega Point" space opera, I agonised over the physics of space-warping in a similar way. Again, little of it got into the text, but I have to know that what is there is completely consistent with the science. Yet the hardest concepts of all are the ordinary human ones – love, jealousy, fear, dependence, and so on. For a recent short story which is to appear in an anthology called Hope, I decided I needed to understand exactly what hope is before I could start. Have you ever wondered? It took me a whole month to get my feeble brain around that one. A month in which I did nothing constructive at all and drove my wife crazy as I tried out new "insights" on her day after day. It's a kind of writer's block, I suppose, but one that always, always leads to a better story in the end.

Right now, I'm grappling with an old friend: the antipathy between empathy and psychopathy and how far a character whose nature is dominated by one can be led by circumstances towards the other. This conundrum and I went twelve rounds during the writing of my last-but-one novel, Mindrider, in which my protagonist was a rather unpleasant, alien brain parasite. I think I won on points, so I suppose it's hardly surprising it is demanding a re-match in my new work in progress, The Sentience Machine.

Writing a novel is such a long way from catching words as they float by and pinning them to the page. It is a massive decision-making process on multiple levels, coupled with a huge effort to understand at least some aspects of the people we are and the universe we inhabit, together with the presentation of all this work in a form that will stimulate and entertain. It is by far the most difficult, most satisfying, and most enjoyable work I have ever done.

July 13, 2011

Sometimes, It's Nine Parts Inspiration

I used to be jealous of William Wordsworth, not just because the guy could write poetry and I suck at it, but because I read once of him conceiving the opening of The Prelude, word-for-word, and later writing it down. It struck me at the time that it was similar to things I'd heard about Mozart (another bloke who was good at something I suck at) that he could imagine a whole symphonic movement, note-for-note. The very idea that people can perform such feats of imagination and memory seems magical to me. Of course, both reports are untested, unverified, and may be apocryphal, but I see no particular reason for doubting them, especially since I recently caught a glimpse of what it must be like.

I'm taking part in another one of Jodi Cleghorn's madcap, crowdsourced anthology projects: a thing called Tiny Dancer. The process is unlike anything else you'll see in publishing and takes about six weeks from go to woe. To cut a long story short, you end up with what is, essentially, a writing prompt – a line from the lyric of a popular song – and you write a 1500-word spec. fic. story based on that and a theme Jodi provides. I got my line just before bedtime and went to sleep mulling it. Then, BAM, I was wide awake at 4 am with the story in my head. And I don't just mean an idea for the story, the feel of the story, a plot for the story, the way it usually happens. I mean I had the story – words and all. I fought it for a while, trying to get back to sleep but, in the end, realising how crazy I'd be to look this gift-horse in the mouth, I got up and wrote it down.

It turned out I didn't have all the words I needed and the detailed structure of the piece required some work, but by the time I'd finished writing it and revising it, I'd say about half the original story survived – including whole paragraphs transcribed verbatim from the original inspiration.

I'm feeling pretty pleased with myself. Not only did I write a story in a couple of hours that I might have agonised over for weeks, but I have slain my personal dragons of Wordsworth and Mozart. In your faces, brilliant geniuses! My story may not be The Prelude, or Don Giovani, but it helped me share one of those astounding experience I have hitherto only read about. It wasn't as perfect as it might have been, either, indeed, as some dead geezer once wrote, "an ill-favored thing, sir, but mine own."

May 26, 2011

Review: The Believing Brain by Michael Shermer

(This review first appeared in the New York Review of Books.)

(This review first appeared in the New York Review of Books.)

Belief comes first, rationalizations follow behind. That is the basic theme of this new book on belief by professional sceptic, Michael Shermer. Belief comes first because we're wired that way, Dr. Shermer says. We see patterns in everything (sometimes even when they aren't there) and we are disposed to see an active agent behind every pattern (even the false ones, and even when there is no one there.) According to Dr. Shermer, finding patterns in the world and ascribing agency to their creation is the foundation for beliefs of all kinds, from political opinions, through conspiracy theories, to alien abductions, gods and demons.

As evidence that we are avid pattern-finders, Dr. Shermer presents psychological results going back to the operant conditioning of "superstitious" behaviour in animals by B.F. Skinner and the other Behaviourists, the work of ethologists like Konrad Lorenz on "imprinting", and from other areas such as face recognition, and pattern finding under uncertainty. It is a solid and well-established case, backed up by more recent work by Susan Blackmore on how people who are believers in the supernatural are more likely to see patterns in noisy images than non-believers. He also believes there are good evolutionary reasons for us being this way.

For our tendency to ascribe agency, he cites the work of psychologist Bruce Hood, looks at out of body experiences, tells of his own experiences with Michael Persinger's "God Helmet" (which induces neuron firing in the temporal lobes using strong magnetic fields, during which some subjects have reported intense religious experiences.) He also discusses magicians and skilled illusionists and the work of Randi and others in debunking them. Here Dr. Shermer's case is weaker, relying heavily on personal anecdotes rather than on scientific studies.

To convince us that belief always precedes reasoned argument, Dr. Shermer takes us on an extended tour of beliefs of various kinds – political, religious, conspiracy theories, alien abductions, and so on. If you've read other books by Dr. Shermer – particularly Why People Believe Weird Things and The Mind of the Market – you'll already be familiar with most of the material here.

While fascinating in places and challenging in others, it is, in the end, disappointing. The mass of anecdote, sprinkled with odd bits of science, is not convincing and often seems to ramble away from the central argument. There is a curious section in which Dr. Shermer attempts to mount a scientific defence of free market economics, which will no doubt be as irritating to a liberal reader as it is unconvincing to a scientist. In fact, it illustrates Dr. Shermer's theme perfectly – albeit unintentionally – by showing how scientific findings can be cherry-picked to build arguments around a belief that is already entrenched in the author's mind.

Having presented the case that we form beliefs on the basis of unconscious, often irrational processes, and that all our argumentation in support of these beliefs is then added post hoc and subject to a wide range of cognitive biases which he lists and explains, Dr. Shermer leaves us in a near-hopeless state. The human condition, according to this perspective, is one of deep-rooted, biased subjectivity and perpetual, unresolvable conflict between believers with different sets of beliefs.

To save us from this conclusion, he attempts, at the end of the book, to present the scientific method as a way out of the morass. By basing judgements of truth on what is repeatedly observable by anyone making those observations in the same circumstances, and by insisting that explanations of observations are themselves to be subject to tests whose outcomes must also be observable by anyone who performs them in the same way, science might cut through the fog of individual bias, superstition and prejudice, to yield something like a true understanding of the world. "The God question" he says, is only immune to scientific examination as long as you only make claims about gods that can not, even in principle, be examined with the scientific method. Since many claims about gods can quite easily be examined scientifically – like the healing power of prayer – even this area of belief is not wholly immune.

Yet the value he places on objectivity rather than subjectivity, of external rather than internal reality, simply reveal more of his own personal beliefs. Yes, science could cut the Gordian knot of superstition, but only for those whose beliefs match Dr. Shermer's. By his own logic, for those who believe that objective reality is unimportant or even non-existent, arguments which stem from other sets of beliefs will be never be persuasive. In fact, the more convincing we find Dr. Shermer's thesis, the less likely it seems that scientific and superstitious world-views could ever be resolved.

It would be easy to say that you should read this book and make up your own mind, but, if Dr. Shermer is right, you have already made up your mind and this book will either reinforce your beliefs or spur you to challenge the author's. Nevertheless, this reviewer's belief is that a good dose of scepticism is always healthy, having your beliefs challenged is always good for you, and these things are exactly what you can count on from this book.

May 19, 2011

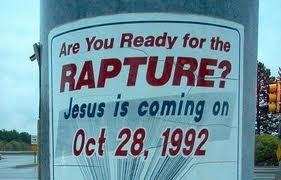

Is This Goodbye?

Ah well, better luck next time.

After all, it's the Rapture tomorrow. This could be the last anyone hears from me. Which gives me such a cool idea. What if I just disappear tomorrow – take no luggage, no credit cards, leave no note, just vanish. I could then sit on a beach in Northern Queensland reading the religious nutcases speculating in the press as to why I was the only one in the world taken in the Rapture. They would probably find some good reason.

So, if I do disappear, either God's got a really cool sense of humour, or I have.

Meanwhile, you might like to know that writer, Sonya Clark, turned her Digital Author Spotlight on me today, and hosted a guest post from me. Yes, I began life as a digital-only author, but one day… So a big thank you to Sonya and to all of you who just clicked the link and went to have a look.

See you tomorrow – or will I?

May 17, 2011

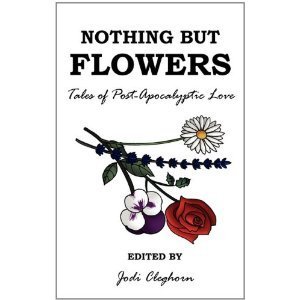

Nothing but Flowers: Post-Apocalyptic Love Stories – out now

Tales of Post-Apocalyptic Love

Remember me mentioning some upcoming anthologies with stories of mine in them? Well, one is out today. So shoot over to Amazon and grab your copy. All proceeds to to help Queensland flood victims. These guys lost a lot and are still suffering, so if you're feeling charitable, this is definitely a good cause. There are 26 stories in all and mine is called "Two Fools in Love". (In case you just want to jump straight there. Just a suggestion.)

Here is where to buy it: http://www.amazon.com/Nothing-But-Flowers-tales-post-apocalyptic/dp/098074461X/ref=cm_wl_cp_al_pt

The publisher, eMergent Press, wants you to buy it right now, this minute, to create an Amazon "chart rush", which will help sales and mean more money for charity. But any time that suits you is just fine, really.