Graham Storrs's Blog, page 15

March 6, 2012

The Trouble With Poets

The Trouble With Poets

The trouble with poets

Is that they sound so clever.

But have you noticed

How they never answer

Those profound questions,

Never resolve those

Sonorous ambiguities?

Singing isn't so hard.

Birds and frogs can do it.

Getting the world

To tell you one, simple truth, though,

Is like pulling teeth.

March 2, 2012

Review: The Helios Conspiracy by Jim DeFelice

(This review first appeared in the New York Journal of Books.)

(This review first appeared in the New York Journal of Books.)

Jim DeFelice hardly needs any introduction to lovers of techno-thrillers. And for the fans, his new book The Helios Conspiracy is not likely to be a disappointment.

A monomaniacal scientist with plans to save the world from the looming energy crisis by launching solar collectors into space has his top engineer and manager murdered at a crucial moment. Then the launch of the first satellite fails, leaving a beautiful rocket scientist wrapped up in the problem of how and why.

Enter the tough FBI agent with a special interest in what's going on—the murdered engineer was his ex-girlfriend and she'd called him just hours before her death to ask for his help. Suspects are thick on the ground—the Russians, the Chinese, and a ruthless financier who has been applying pressure to gain control of this new technology. But that is just the beginning.

The Helios Conspiracy is the third of Jim DeFelice's books to feature FBI Special Agent Andy Fisher. Fisher may not actually save the lives of millions this time around (as he did in Threat Level Black), but for him, the stakes are just as high because, as they say, this time it's personal.

However, while the fans may be happy, other readers may not be. There is something flat about the story despite all the action. We move from scene to scene as if touring a number of set piece tableaux in a museum ride. Our hero is motivated and dogged, but somehow he seems too tired and world weary to be giving it his best efforts. You get the impression he'd really rather sit in a diner and eat fries all day. And that's not all that's wrong with Andy Fisher.

The hero of the tale is so hard-bitten you can see the toothmarks, so tough you could reinforce concrete with him. He lives on a diet of junk food, cigarettes, and bad coffee, never works out, and yet goes on operations with Navy SEALS when the fancy takes him. He must be one mean-looking SOB too, because, despite being curt beyond the point of rudeness, and rude to the point where even a saint would deck him, no one so much as tells him where to shove it. In short, he is such an extreme example of the genre stereotypical tough guy, he is almost a parody of it. It is sometimes very hard to take him seriously—especially the part where he is meant to be well read and highly educated. This is not the kind of man you can imagine curling up with a good book.

The Helios Conspiracy is a solid thriller-cum-detective story. If you've read the other Andy Fisher books, or you can't get enough of Jim DeFelice, you'll probably love it. Even with the stilted plot and the flat emotional feel, it is well written enough to keep you turning pages to the end.

Review: The Quantum Universe by Cox and Forshaw

(This review first appeared in The New York Journal of Books.)

(This review first appeared in The New York Journal of Books.)

Quantum theory has a bad rap. It is a by-word for strangeness. It is arguably the main reason why so few people understand or trust science anymore. So a book that promises "to demystify quantum theory" is offering something quite special.

Its authors, Professors Brian Cox and Jeff Forshaw, both physicists at Manchester University in the U.K., have good credentials when it comes to demystification. Their previous book Why Does E=mc2? [see my review in the New York Journal of Books] did an excellent job of living up to its ambitions and gave us deep insights into how Special Relativity works.

The Quantum Universe takes essentially the same approach as this earlier work. It presents some of the inexplicable findings that were plaguing scientists at the end of the 19th century—such as the discovery of unique spectral patterns emitted by different materials—and shows how theoreticians in the early part of the 20th century came up with a radical new explanation for them, first expressed by Heisenberg in 1925.

Professors Cox and Forshaw do not dwell on the history of the subject, merely mentioning the contributions of Schroedinger, Bohr, Dirac, Einstein, and the others, and instead quickly give the reader a chance to do some real exploration of the theory by guiding us through the derivation of Heisenberg's famous Uncertainty Principle.

To avoid difficult mathematics (like manipulating complex numbers) they introduce us to Feynman's use of little clock diagrams to represent quantum states. It works well at first, but later in the book the feeling that the clock diagrams are doing a bit too much work begins to grow—we are soon talking about clusters of clocks and, eventually, clocks which represent sets of clocks. By the end of the book, the reader might be feeling that it would have been better to have taken the plunge and learned the maths.

After the triumph of deriving Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle (one of the most misunderstood and over-interpreted ideas ever) the book moves to more practical matters, like describing the workings of a transistor. The authors are quite right in saying that the transistor has been a world-changing invention, and its operation can only be understood in quantum terms, yet the amount of space devoted to explaining it seems disproportionate to its inherent interest. Worse still, to introduce the many ideas needed to follow the explanation, the text becomes quite stodgy and didactic. The authors even make self-conscious apologies for their classroom tone.

Finally, with the help of another graphical tool, the Feynman diagram, The Quantum Universe (And Why Anything That Can Happen Does) moves into broader areas of how particles interact. It also talks about how particles might get their mass, what anti-matter is, the measurement problem, and similar fun topics, and ends on a whole chapter calculating the Chandrasekhar mass (the upper limit on the mass of a white dwarf star) from first principles.

Sadly, it turns out that quantum theory really is weird. Don't think that reading The Quantum Universe by Professors Cox and Forshaw will make any of that weirdness go away. In fact, the more you learn about it, the more weird it is going to seem.

The state of an electron depends on the state of every other electron in the universe. Inexplicable constants abound. Rules like Pauli's Exclusion Principle explain the data but cannot themselves be explained. Particles (which are also waves) are point-like, having no physical extent. And so on.

As Richard Feynman famously wrote, "I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics."

But understanding the quantum world in the deep and satisfying way that we'd like to is not at all necessary to describe its workings with exquisite precision. It is this astonishingly accurate mathematical description of the consequences of a set of rules that, as strange as they may seem, actually work, that is the focus of Professors Cox and Forshaw's brief excursion through the looking glass.

It is an approach they jokingly describe as the "shut up and calculate" school of physics, but it emphasizes one of the important underlying messages of the text.

Quantum theory is weird, yes, but it absolutely has to be the way it is in order to explain the weird behavior of the world we live in. A theory that did not explain wave-particle duality as revealed in the famous "double slit" experiment, would be worthless. Quantum theory does the job and much, much more. And if it paints a picture of the universe that boggles our minds, the best we can do is take it seriously and accept the limits of our imagination.

The Quantum Universe may not demystify quantum theory, but it does give the reader an idea of the size of the mountain the book is trying to climb—and a toe-hold or two to help get us started on our own ascent.

February 14, 2012

Talking TimeSplash and Kindle at Patty Jansen’s Blog

Just a very quick note to say you should pop over to Patty Jansen’s blog where I have a guest post about my experiences with the Kindle Select programme. Patty describes it as “a wild ride” and she’s absolutely right. See you over there.

Talking TimeSplash and Kindle at Patty Jansen's Blog

Just a very quick note to say you should pop over to Patty Jansen's blog where I have a guest post about my experiences with the Kindle Select programme. Patty describes it as "a wild ride" and she's absolutely right. See you over there.

February 10, 2012

Review: The Fear Index by Robert Harris

(This review first appeared in the New York Journal of Books.)

(This review first appeared in the New York Journal of Books.)

As the world's financial systems crumble about our ears, it may be a good time to reflect on the perils of automatic trading. For all the rules and safeguards in all the stock exchanges of the world, isn't it just possible that in a quiet office in London, or New York, or Geneva, a genius mathematician has developed an algorithm so smart that it can out-game the electronic stock exchanges, a program so fast and complex even its designers can't keep up with it, and so amorally reckless, that it would do literally anything to make a buck? Of course it's possible, and that's why the premise of The Fear Index by Robert Harris is seriously creepy.

The novel is self-consciously a Frankenstein story—the quote from Mary Shelley at the top of Chapter One gives that away—but the "monster" is refreshingly credible, and author Harris's "Dr. Frankenstein"—a genius mathematician, Dr. Alexander Hoffmann—has no intention whatsoever of creating life.

Hoffmann has been working at CERN on a physics problem, building an artificial intelligence on the side. To give his learning algorithm something meaty to chew on, he programs it to work the stock market—where it earns enough to pay for Hoffmann's hobby. When a hedge fund manager called Hugo Quarry discovers Hoffmann and his little project, the pair team up and take it to a whole new level.

They build a multibillion-dollar hedge fund, making themselves and their investors very rich. But Hoffmann is not really interested in the money, he just wants to keep on improving his AI, and now he has all the money he needs and a team of analysts to help him.

That the project goes off the rails goes without saying. The "positions" the algorithm takes in the market become more extreme, but also more successful. At the same time, Hoffmann finds himself targeted by a deranged killer, bank accounts he didn't know he had are being used to make incriminating purchases, and a market collapse no-one had foreseen is successfully predicted by the algorithm after a terrorist attack on a commercial flight.

Pretty soon, Hoffmann is on the run from the police, trying to clear his name and save his marriage, while at the same time trying to understand what his own software is up to.

Yes, it's a well-worn plot and, yes, several of the characters are exactly what you'd expect—the head-in-the-clouds genius, the provincial but sharp policeman, and so on—but this is not a piece of hack work.

The writing is good and the story is freshened by three things: Hugo Quarry, the protagonist's friend and partner, who is an interesting and believable character; the accurate and credible depiction of the complex world of derivatives trading; and the "monster" itself.

The AI at the root of all Hoffmann's troubles is one of the most intelligently drawn software creations you are likely to come across. It doesn't talk; it doesn't display any emotion; it isn't trying to conquer the world or impregnate the beautiful heroine; it just does what it was built to do: make money. And while it is never at the front of stage until the end of the book, we feel its menacing presence on every page.

The Fear Index is a solid, competent techno-thriller, carefully researched and intelligently executed. If you enjoy this genre—and who doesn't now and then?—put this one on your to-be-read list.

February 4, 2012

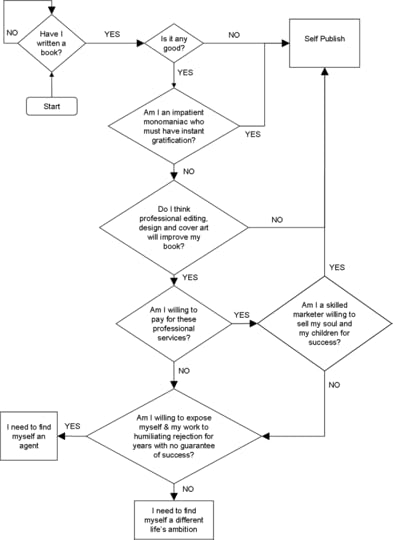

Should You Self-Publish? How to Make the Decision

It is the question on every writer's lips these days and the subject of countless blog posts. However, here is the first comprehensive and dispassionate guide to making this career-defining decision. The flowchart below will guide you through all the essential questions. Answer each one honestly and I guarantee you will come to the right choice for you.

Instructions:

Start at the box labelled "Start" and follow the arrow.

Answer each question YES or NO – you are not allowed any maybes. And follow the associated arrow.

Take the advice you end up with and get on with your life.

It's as easy as that.

Click the flowchart for a larger image

January 17, 2012

Best-Seller for a… Couple More Days

Last weekend (was that just three days ago?) I had a free book giveawy on Amazon for my time travel thriller, TimeSplash (that's it in the left-hand column if you want to pick up a copy). As my previous post says, it was an exciting moment. A book that had spent almost two years in relative obscurity, was being grabbed up by thousands of people. In fact, in the course of two days, over 19,000 people downloaded the book. In the "Free in the Kindle Store" listings, it shot to #1 in Science Fiction, #1 in Techno-thrillers and #13 overall.

It was wild and dizzying ride. If you're not a struggling writer, you may not be able to imagine what it means to have so many people wanting your book all at once. Remember that moment when you first realised that the girl or guy you had fallen in love with actually loved you back? It was sort of like that but without the hope of a happy ever after. That's because, after the free offer period, my book was going back into the "Paid in the Kindle Store" listings and all those nice high rankings would evaporate in an instant. So I steeled myself for the come down, the plunge back down to the dark and obscure depths to which it had slowing been sinking. (I don't know how far down the Amazon Kindle ranks go. I've noticed books with ranks as low as 800, 000. It must be very cold and still at those depths, with soul crushing pressures.)

And then something peculiar happened. TimeSplash fell alright, but it didn't fall very far (down to about #1000 overall) and then it started drifting back to the surface. Within a day, it had regained its #1 spot in Techno-thrillers – but this time in the "paid" ranks, of course, and was at #60-something in Science Fiction. The next day, I woke to find it at #11 in Science fiction and went to bed last night with it at #5, where it seems to have come to rest. It was still there when I woke up this morning, only now my overall rank has drifted up above #200 – the highest it has ever been.

Since the upward movement seems to have slowed, I imagine it won't be long before the downward drift starts in earnest. Which is sad, but it was fun while it lasted – and I sold a truckload of books and actually made some real money out of writing for a change. I also managed to loan a few books through the Kindle library – which will translate to further earnings, although I have no way of calculating how much. And I got a handful of very good Amazon reviews out of it. (Well, three excellent ones, one that compared TimeSplash very favourably to Stephen King's 11.22.63 and scared me to death, and one in which the reader said she liked it but then went on about all the many ways she had been confused by it all. With which one can only sympathise.)

Also, I think I've learned a few things about how this all works.

1. Because Amazon lists the Paid and Free books side-by-side in its "Top 100″ pages, anyone looking at the best-selling books in, say, Sci-Fi, will see the most downloaded free books too. I can only assume that this is the mechanism by which the giveaway led to my book being noticed and then bought by so many people.

2. Equivalent ranks in the free and paid lists are by no means equivalent in terms of the numbers of books you have to shift to achieve them. To get a particular rank in the free lists, it seems you need to give away as many as 30 times more books than you need to sell for the same rank in the paid lists.

3. There is a vast difference between the UK and the USA when it comes to free book grabs. The Americans seem very keen on free books. They are well organised too. There are blogs and websites that track when free books appear on Amazon and spread the word to their subscribers. My guess is that there must be tens of thousands of such subscribers at the very least, perhaps hundreds of thousands. Thus, of the 19,000 I gave away last weekend, fewer than 2% of them went to the UK and Europe. As a consequence of this (and point 1) almost all the subsequent sales have been to the USA. The book just never made it onto Europe's radar. All I can say to this is, God bless America!

4. Whatever the drawbacks of Amazon's KDP Select programme (and their insistence on exclusivity is the biggest) it definitely worked with this particular book. As it happens, another book of mine went into the scheme and had a free book period last week with a very different outcome. The uptake was in hundreds not thousands and the after-sale bounce did not happen. Since the gaveaway, I have sold 2 copies of that book. Which just means there are all kinds of variables at play – timing, type of book, pricing, cover, blurb, etc. – and I'd need a lot more data before I could tell you definitely to go for KDP Select. All I can say is that it worked for me once, and didn't work for me once.

5. Having scaled these dizzying heights for the first time ever, it has given me a new insight into the volume of sales being achieved by the big names in my genre. Wile I expect to climb up and fall back down fairly quickly, there are some who are up there selling hundreds of books every single day for months, years, even decades. It is a very humbling thought and puts one's success into perspective.

And, as a footnote to all that, I add that in the time it took to write this post, the book climbed a little farther in the ranks. It just moved to #4 in Science Fiction, bumping Orson Scott Card's brilliant Ender's Game into fifth position. (Sorry, Orson. I didn't mean it. I'm not worthy.)

January 13, 2012

Best-Seller for a Day

I signed my novel, TimeSplash, into the KDP Select programme the other day because I was hoping it might give it a bit of a boost. It has been two years since the book was first published and sales have started flagging. Select gives you the option to promote your books by offering them for free for five days during the 90 exclusivity period. So, to dip my toe in the water, I set up two days – yesterday and today – to give TimeSplash away for free.

The result has been breathtaking.

As I write, TimeSplash is number 1 in the Kindle Store for Science Fiction, number 1 for Technothrillers, and number 28 overall. There have been thousands and thousands of downloads in the past 24 hours and the book is still climbing! What a day I'm having.

Of course, it will all be over tomorrow. The free offer will end, the book will go back into the "paid" rankings and I'll lose the rankings I now have in the "free" section. It's a shame (but fair). On the other hand, I got to experience, just for a little while, what it must feel like to have an actual best-seller climbing the charts. And I'll tell you what, it feels fantastic.

And to all those thousands of people who downloaded the book (my site stats tell me that many of you are stopping by here), thank you for this great day. I hope you enjoy the book. And if you do, pop back to Amazon and leave a review for the book, why not? It will help me sell a few copies in between giveaways

January 7, 2012

Hold the Front Page: Writer Found in Rural Australia

As you may know, I live out in the Boondocks, the sticks, Woop Woop (or pick your own quaint phrase meaning "the middle of nowhere"). The main industries here are fruit growing and wine making. They play country and western musak in the local supermarket and the churches outnumber the pubs about twenty to one. In this week's local free rag – which is actually a half-way decent local paper if you can stand the unrelenting right-wing political bias – the front page story (and when I say front page, I mean it fills the whole front page, including a half-page photo) is about a local writer who has had a book published. The story wasn't just that, of course, although the very existence of a local writer would have been newsworthy enough, it focused on the scale of the bloke's success. His book has been published internationally, you see. Not only that but he has never had a rejection letter. The first publisher he approached snapped it up.

Of course, I was amazed, not to say a little miffed, that my own publishing success has gone completely unremarked in the local press. I read the article again, thinking I might find out who the bloke is and maybe look him up some time. It would be nice to have another writer to talk to whom I could meet in the flesh from time to time. It was then that a comment near the end of the piece caught my eye. The journo referred not to the man's publisher but to his "investor". In a trice I was onto the Web. The publisher of the book turned out to be a vanity press. Judging from what was said in the article, the author had bought their deluxe package at about $2,000 – no doubt this also included a carefully-worded press release to send to the local paper. And that, of course, explained why this writer had not received any rejection letters. (How would a rejection letter from a vanity press look? "Dear Mr. X, Thank you for letting us see your manuscript. We receive thousands of excellent manuscripts each year and, unfortunately, we are not able to take your $2,000 at this time. We wish you more success with giving your money to another publisher.")

Still, I do know a few people who have used vanity publishing services over the years and in at least one case, their books are as good as any you might find from a major publisher. In fact, better than the bulk of them. And the article had said how amazingly well this particular book was doing. So I went to Amazon, to see what the fuss was about. There was no opportunity to read a sample, unfortunately, but I did notice that it had been out for six months but had only one customer review (albeit five stars) and its sales rank was around three million. (In case you're new to the mysteries of Amazon, a sales rank of 1 is good. A sales rank of 3,000,000 means nobody is buying. I have no idea what any other number means.) So not really the success the article was making it out to be. In fact (and I have no idea whether the work deserves it, but) it seems to be languishing in obscurity. Perhaps the article in the local paper will improve its fortunes.

A number of thoughts occur to me about all this.

The first is that the journalist and editor who put this on the front page didn't do even some minimal fact checking. This seems to be par for the course with journalists these days – even on newspapers you have to pay for. If they had checked the facts, they might not have printed such a breathless accolade, or described anything as surprising as a first time author who hasn't had a rejection letter. On the other hand, the bloke might just be a relative of the paper's owners or editor. Nearly everybody around here is related to everybody else.

The second is that the journalist, the editor, and perhaps even the author himself, simply do not understand the difference between a publisher and a vanity press. Maybe it is only people in the business who have learned to make this distinction. Maybe the rest of the world hasn't cottoned on yet. The thing is, paying someone to publish your book is not the same as someone paying you to publish your book. Honestly, I don't mean to be snobbish about this. I have self-published a few books (although I have not used a vanity press). Self-publishing and even vanity publishing are not bad things – as long as it is clear to the reader what they are getting. Like it or not, being published by a "traditional" commercial publisher (large or small) is the reader's implied guarantee of a minimum level of quality. Self-publishing and vanity publishing mean there is no implied promise of a minimum quality level and the reader must take pot luck (or insist on reading a free sample before purchase).

The third is that I really ought to be more aggressive and mendacious about marketing my stuff.