Grace Elliot's Blog: 'Familiar Felines.' , page 14

November 20, 2013

Manchester Square - Joanna Southcott and the Pig-faced Lady

Hertford House in the present day.A shorter post today as I am recovering from a migraine.

Hertford House in the present day.A shorter post today as I am recovering from a migraine.

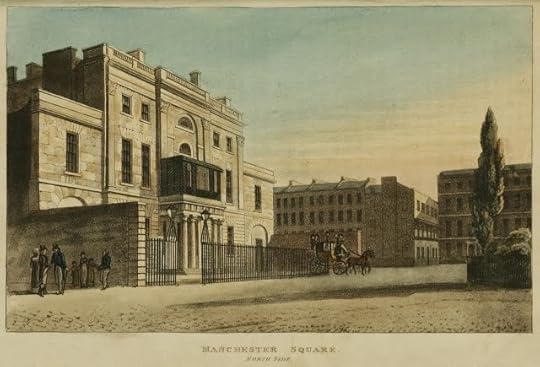

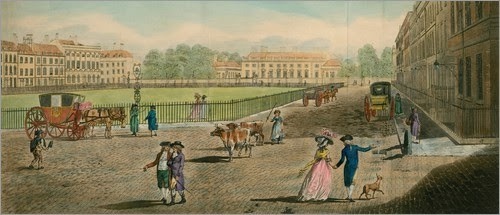

Manchester Square in 1830

Manchester Square in 1830Hertford House on the left (now home of the Wallace Collection)

My husband's office is in Manchester Square, London, and I was curious to find out about the people who lived and worked there in the past. Firstly, the most dominant building in Manchester Square is the home of Wallace Collection. Built by the Duke of Manchester (and named accordingly) in 1797 it was bought by the Marquess of Hertford, and renamed Hertford House. The collection boasts many fine art works.

Above - The Princes in the Tower - the Wallace collection.

Above - my favourite painting in the Wallace collection-my Granny had a much loved biscuit tin with this picture on the lid

A famous inhabitant of Manchester Square was Joanna Southcott. In 1792 she made public her ‘gift of prophecy’ and predicted the French Revolution heralded an apocalypse with Napoleon as her antichrist. Joanna made some of her prophecies public during her lifetime, but others she kept secret. The latter were written down and locked in a sealed box with instructions only to open it at a time of national crisis and in the presence of the 24 Bishops of the Church of England. The whereabouts of this box is disputed, but some say it was opened in 1927 and found to contain a lottery ticket, lacy night-cap and a pistol.

Above - Joanna SouthcottAt the age of 64, in 1814, she declared herself pregnant with ‘the Prince of Peace’ and that she would give birth to a messiah, called Shiloh. She implied the child was the result of divine conception by “the power of the Most High” and her offspring would “rule the nations with a rod of iron.” However, it seems likely that Joanna’s swollen belly was actually a huge tumour since no baby was forthcoming and she died at home in Manchester Square in December 1814.

'Spirits at work' - Joanna's conception

'Spirits at work' - Joanna's conception1814 was a busy time for the square as it was rumoured another famous resident lived there. “There is at present a report in London of a woman, with a strangely deformed face, resembling that of a pig, who is possessed of a large fortune…” The Times 1714

With thanks to Wellcome ImagesApparently many hundreds of people sought out this poor woman, including Lord Kirkcudbright – who being hunchbacked and dwarfish wanted to sympathise with someone equally challenged in looks. However, for whatever reason the pig-faced woman was a hoax, perhaps created by the media to make the point of how easily people were led.“The pig’s face is as firmly believed in by many, as Joanna Southcott’s pregnancy, to which folly it has succeeded…there is hardly a company in which this swinish female is not talked of, and thousands believe in her existence.”

With thanks to Wellcome ImagesApparently many hundreds of people sought out this poor woman, including Lord Kirkcudbright – who being hunchbacked and dwarfish wanted to sympathise with someone equally challenged in looks. However, for whatever reason the pig-faced woman was a hoax, perhaps created by the media to make the point of how easily people were led.“The pig’s face is as firmly believed in by many, as Joanna Southcott’s pregnancy, to which folly it has succeeded…there is hardly a company in which this swinish female is not talked of, and thousands believe in her existence.”

Published on November 20, 2013 00:43

November 13, 2013

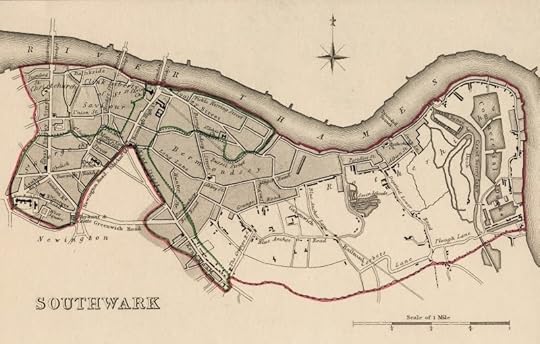

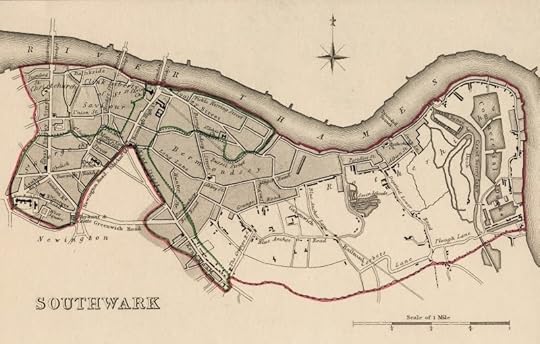

London Then and Now: Southwark

This may interest only me… Four weeks ago my son left home and moved into a flat in Southwark. After the long walk from London Bridge tube station to his new abode, my appetite was whetted to investigate the history of this part of South London.

My son's new home- a converted Victorian pub 'The Duke of York'.The history of Southwark predates the Norman Invasion and it appears King Cnut granted Earl Godwin a third of the profits taken the river trade (the king had the other two-thirds). But Godwin’s rites lapsed after his death and his successive generations more or less constantly petitioned the crown for restoration of this valuable privilege. From the 1100’s to the 1500’s a variety of noblemen coveted the tolls and taxes raised from traffic on the Thames. But by the 1550’s King Edward VI had largely absorbed Southwark into the city of London and put it under the same rule of law as the rest of the capital.

My son's new home- a converted Victorian pub 'The Duke of York'.The history of Southwark predates the Norman Invasion and it appears King Cnut granted Earl Godwin a third of the profits taken the river trade (the king had the other two-thirds). But Godwin’s rites lapsed after his death and his successive generations more or less constantly petitioned the crown for restoration of this valuable privilege. From the 1100’s to the 1500’s a variety of noblemen coveted the tolls and taxes raised from traffic on the Thames. But by the 1550’s King Edward VI had largely absorbed Southwark into the city of London and put it under the same rule of law as the rest of the capital.

Southwark - south of the ThamesIn Georgian times people were in no hurry to live on what was an area of marshy scrubland. However, industry flourished on the banks of the Thames – powered by water mills. The area was especially well-known for leather production but tanneries used dog faeces and human urine for part of the process and emitted vile fumes. Indeed, the south bank of the Thames was described as ‘hideous’with ‘dank tenements, rotten, wharves and dirty boat houses.’

Southwark - south of the ThamesIn Georgian times people were in no hurry to live on what was an area of marshy scrubland. However, industry flourished on the banks of the Thames – powered by water mills. The area was especially well-known for leather production but tanneries used dog faeces and human urine for part of the process and emitted vile fumes. Indeed, the south bank of the Thames was described as ‘hideous’with ‘dank tenements, rotten, wharves and dirty boat houses.’

Borough market - circa 1860In 1622 the leather dressers of Southwark petitioned against the damage done to their trade by an influx of Dutchmen leather workers who did not serve that same apprenticeship and undercut their prices.Up to about 1780 the built up parts of Southwark centred on the south end of London Bridge and the rest of the borough was relatively rural, encompassing an area of land on the south side of the Thames including Borough, Bermondsey and Bankside. The latter, Bankside, was the traditional home of bear-baiting, and although this cruel sport was banned under the Puritan’s with the Restoration the Bankside Bear Garden was resurrected. However, Borough had a gentler reputation - for trading in fruit and veg.

Borough market - circa 1860In 1622 the leather dressers of Southwark petitioned against the damage done to their trade by an influx of Dutchmen leather workers who did not serve that same apprenticeship and undercut their prices.Up to about 1780 the built up parts of Southwark centred on the south end of London Bridge and the rest of the borough was relatively rural, encompassing an area of land on the south side of the Thames including Borough, Bermondsey and Bankside. The latter, Bankside, was the traditional home of bear-baiting, and although this cruel sport was banned under the Puritan’s with the Restoration the Bankside Bear Garden was resurrected. However, Borough had a gentler reputation - for trading in fruit and veg.

Borough Market in the modern dayBorough Market sold market-garden produce grown in Kent and Surrey. Not to be outdone Southwark was also famous for hot house fruits. In 1755 an article in the London World notes:‘Through the use of hothouses…every gardener that used to pride himself in an early cucumber can now raise a pineapple.’ Borough Market still exists to this day – as does another vibrant place of outdoor commerce, East Street Market (which is near my son’s flat) and sells everything from cutlery to bowls of fresh fruit, and second hand clothing to fake perfume.

Borough Market in the modern dayBorough Market sold market-garden produce grown in Kent and Surrey. Not to be outdone Southwark was also famous for hot house fruits. In 1755 an article in the London World notes:‘Through the use of hothouses…every gardener that used to pride himself in an early cucumber can now raise a pineapple.’ Borough Market still exists to this day – as does another vibrant place of outdoor commerce, East Street Market (which is near my son’s flat) and sells everything from cutlery to bowls of fresh fruit, and second hand clothing to fake perfume.

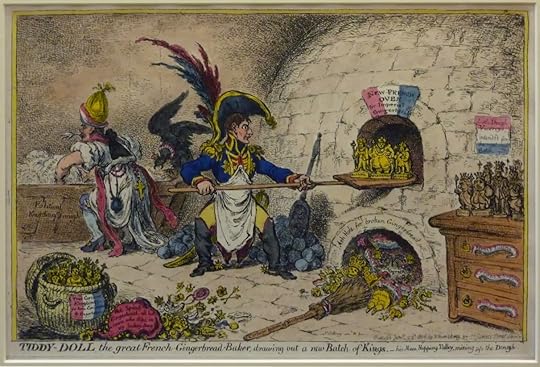

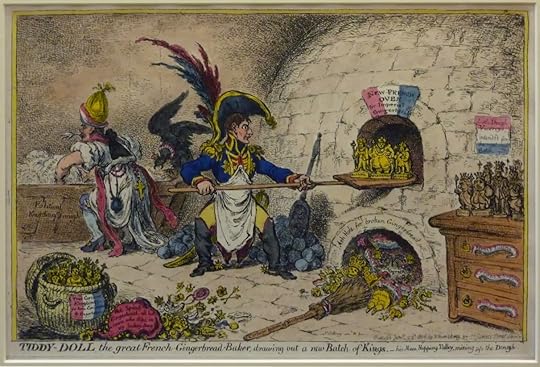

Southwark Fair by Hogarth - 1733In Georgian times Southwark held a fair so well-known that it caught the interest of William Hogarth. His etching of Southwark Fair is evocative of the lively, bawdy atmosphere and denotes some of the local characters. Can you spot the famous gingerbread seller, Tiddy Doll? (He wears a hat with an enormous feather and gold lace banding.) Tiddy was such a character that James Gillray also recorded him in a print ‘Tiddy-Doll the great French Gingerbread-maker, drawing out a new batch of Kings.’ Apparently Tiddy was so popular he leant his name to a number of London eating houses - the last of which closed in Mayfair in the late 1990's.

Southwark Fair by Hogarth - 1733In Georgian times Southwark held a fair so well-known that it caught the interest of William Hogarth. His etching of Southwark Fair is evocative of the lively, bawdy atmosphere and denotes some of the local characters. Can you spot the famous gingerbread seller, Tiddy Doll? (He wears a hat with an enormous feather and gold lace banding.) Tiddy was such a character that James Gillray also recorded him in a print ‘Tiddy-Doll the great French Gingerbread-maker, drawing out a new batch of Kings.’ Apparently Tiddy was so popular he leant his name to a number of London eating houses - the last of which closed in Mayfair in the late 1990's.

Gillray's depiction of Tiddy DollAs to modern times? Much of the area is undergoing redevelopment, as shown by the lovely Burgess Park with its lake, barbecue areas and skate park. The atmosphere is relaxed and the people friendly, and I can’t wait to explore further – including the nearby area of Vauxhall… (More of this another time.)

Gillray's depiction of Tiddy DollAs to modern times? Much of the area is undergoing redevelopment, as shown by the lovely Burgess Park with its lake, barbecue areas and skate park. The atmosphere is relaxed and the people friendly, and I can’t wait to explore further – including the nearby area of Vauxhall… (More of this another time.)

Burgess Park

Burgess Park

My son's new home- a converted Victorian pub 'The Duke of York'.The history of Southwark predates the Norman Invasion and it appears King Cnut granted Earl Godwin a third of the profits taken the river trade (the king had the other two-thirds). But Godwin’s rites lapsed after his death and his successive generations more or less constantly petitioned the crown for restoration of this valuable privilege. From the 1100’s to the 1500’s a variety of noblemen coveted the tolls and taxes raised from traffic on the Thames. But by the 1550’s King Edward VI had largely absorbed Southwark into the city of London and put it under the same rule of law as the rest of the capital.

My son's new home- a converted Victorian pub 'The Duke of York'.The history of Southwark predates the Norman Invasion and it appears King Cnut granted Earl Godwin a third of the profits taken the river trade (the king had the other two-thirds). But Godwin’s rites lapsed after his death and his successive generations more or less constantly petitioned the crown for restoration of this valuable privilege. From the 1100’s to the 1500’s a variety of noblemen coveted the tolls and taxes raised from traffic on the Thames. But by the 1550’s King Edward VI had largely absorbed Southwark into the city of London and put it under the same rule of law as the rest of the capital.

Southwark - south of the ThamesIn Georgian times people were in no hurry to live on what was an area of marshy scrubland. However, industry flourished on the banks of the Thames – powered by water mills. The area was especially well-known for leather production but tanneries used dog faeces and human urine for part of the process and emitted vile fumes. Indeed, the south bank of the Thames was described as ‘hideous’with ‘dank tenements, rotten, wharves and dirty boat houses.’

Southwark - south of the ThamesIn Georgian times people were in no hurry to live on what was an area of marshy scrubland. However, industry flourished on the banks of the Thames – powered by water mills. The area was especially well-known for leather production but tanneries used dog faeces and human urine for part of the process and emitted vile fumes. Indeed, the south bank of the Thames was described as ‘hideous’with ‘dank tenements, rotten, wharves and dirty boat houses.’

Borough market - circa 1860In 1622 the leather dressers of Southwark petitioned against the damage done to their trade by an influx of Dutchmen leather workers who did not serve that same apprenticeship and undercut their prices.Up to about 1780 the built up parts of Southwark centred on the south end of London Bridge and the rest of the borough was relatively rural, encompassing an area of land on the south side of the Thames including Borough, Bermondsey and Bankside. The latter, Bankside, was the traditional home of bear-baiting, and although this cruel sport was banned under the Puritan’s with the Restoration the Bankside Bear Garden was resurrected. However, Borough had a gentler reputation - for trading in fruit and veg.

Borough market - circa 1860In 1622 the leather dressers of Southwark petitioned against the damage done to their trade by an influx of Dutchmen leather workers who did not serve that same apprenticeship and undercut their prices.Up to about 1780 the built up parts of Southwark centred on the south end of London Bridge and the rest of the borough was relatively rural, encompassing an area of land on the south side of the Thames including Borough, Bermondsey and Bankside. The latter, Bankside, was the traditional home of bear-baiting, and although this cruel sport was banned under the Puritan’s with the Restoration the Bankside Bear Garden was resurrected. However, Borough had a gentler reputation - for trading in fruit and veg.

Borough Market in the modern dayBorough Market sold market-garden produce grown in Kent and Surrey. Not to be outdone Southwark was also famous for hot house fruits. In 1755 an article in the London World notes:‘Through the use of hothouses…every gardener that used to pride himself in an early cucumber can now raise a pineapple.’ Borough Market still exists to this day – as does another vibrant place of outdoor commerce, East Street Market (which is near my son’s flat) and sells everything from cutlery to bowls of fresh fruit, and second hand clothing to fake perfume.

Borough Market in the modern dayBorough Market sold market-garden produce grown in Kent and Surrey. Not to be outdone Southwark was also famous for hot house fruits. In 1755 an article in the London World notes:‘Through the use of hothouses…every gardener that used to pride himself in an early cucumber can now raise a pineapple.’ Borough Market still exists to this day – as does another vibrant place of outdoor commerce, East Street Market (which is near my son’s flat) and sells everything from cutlery to bowls of fresh fruit, and second hand clothing to fake perfume.

Southwark Fair by Hogarth - 1733In Georgian times Southwark held a fair so well-known that it caught the interest of William Hogarth. His etching of Southwark Fair is evocative of the lively, bawdy atmosphere and denotes some of the local characters. Can you spot the famous gingerbread seller, Tiddy Doll? (He wears a hat with an enormous feather and gold lace banding.) Tiddy was such a character that James Gillray also recorded him in a print ‘Tiddy-Doll the great French Gingerbread-maker, drawing out a new batch of Kings.’ Apparently Tiddy was so popular he leant his name to a number of London eating houses - the last of which closed in Mayfair in the late 1990's.

Southwark Fair by Hogarth - 1733In Georgian times Southwark held a fair so well-known that it caught the interest of William Hogarth. His etching of Southwark Fair is evocative of the lively, bawdy atmosphere and denotes some of the local characters. Can you spot the famous gingerbread seller, Tiddy Doll? (He wears a hat with an enormous feather and gold lace banding.) Tiddy was such a character that James Gillray also recorded him in a print ‘Tiddy-Doll the great French Gingerbread-maker, drawing out a new batch of Kings.’ Apparently Tiddy was so popular he leant his name to a number of London eating houses - the last of which closed in Mayfair in the late 1990's.

Gillray's depiction of Tiddy DollAs to modern times? Much of the area is undergoing redevelopment, as shown by the lovely Burgess Park with its lake, barbecue areas and skate park. The atmosphere is relaxed and the people friendly, and I can’t wait to explore further – including the nearby area of Vauxhall… (More of this another time.)

Gillray's depiction of Tiddy DollAs to modern times? Much of the area is undergoing redevelopment, as shown by the lovely Burgess Park with its lake, barbecue areas and skate park. The atmosphere is relaxed and the people friendly, and I can’t wait to explore further – including the nearby area of Vauxhall… (More of this another time.)

Burgess Park

Burgess Park

Published on November 13, 2013 00:28

November 12, 2013

A Dead Man's Debt #1 best seller in Regency Romance

Please forgive my self-indulgence but moments like this don't come along very often - just had to share.

Published on November 12, 2013 12:00

November 6, 2013

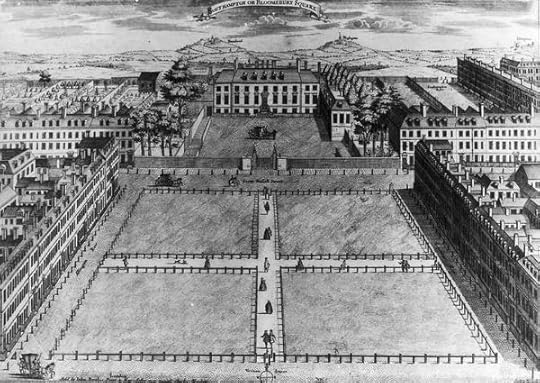

Unofficial London -Then and Now - Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury Square in Georgian timesAfter a recent visit to the British Museum, Bloomsbury, I became intrigued by the history of the area. It is perhaps surprising but this affluent part of London was not always so. Prior to the 1620’s Bloomsbury was part of the parish of St-Giles-in-the-Fields – a place notorious for its lack of law and order. In the early 1700’s things got so bad that something had to be done and so the area was redeveloped. A new parish church was commissioned, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor for a cost of £9,700 – the project went a mere £3 over budget! The improvements were a success and the area continued to expand northwards across marshy fields and farmland. The population expanded form 136 houses in 1624 to 3,000 by the end of the 18th century.‘The fields where robberies and murders had been committed, the scene of depravity and wickedness the most hideous for centuries, became…rapidly metamorphosed into splendid squares and spacious streets; receptacles of civil life and polished society.’

Bloomsbury Square in Georgian timesAfter a recent visit to the British Museum, Bloomsbury, I became intrigued by the history of the area. It is perhaps surprising but this affluent part of London was not always so. Prior to the 1620’s Bloomsbury was part of the parish of St-Giles-in-the-Fields – a place notorious for its lack of law and order. In the early 1700’s things got so bad that something had to be done and so the area was redeveloped. A new parish church was commissioned, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor for a cost of £9,700 – the project went a mere £3 over budget! The improvements were a success and the area continued to expand northwards across marshy fields and farmland. The population expanded form 136 houses in 1624 to 3,000 by the end of the 18th century.‘The fields where robberies and murders had been committed, the scene of depravity and wickedness the most hideous for centuries, became…rapidly metamorphosed into splendid squares and spacious streets; receptacles of civil life and polished society.’ The British Museum

The British MuseumNovember 2013If the mention of Bloomsbury seems familiar, it might be because it is the home of the British Museum. It was the collection of ephemera by a medical practitioner, Hans Sloane, that formed the back bone of this institution. He was an avid collector of artefacts and on his death in 1753, suitable permanent housing needed to be found to protect his acquisitions. King George II declined to help and so the trustees petitioned Parliament to secure the collection for the nation. This they did with success and combined Sloane's artefacts with the Edward Harley’s library and the Cotton Library, in a building not far from Sloane’s old house.

Bloomsbury Square (number 3 - lower edge of the map)

Bloomsbury Square (number 3 - lower edge of the map)British Museum - the grey block to the left of Bloomsbury SquareThe newly formed British Museum was opened on 15 January 1759 and tickets stated: ‘No money is to be given to the servants’ hinting that some employees fancied themselves as tour guides.The area around the museum used to be a farm run by two eccentric sisters. As the area was developed the Capper sisters farm disappeared beneath the building of the new University College, whilst the farmhouse stood on Tottenham Court Road – it was used as a storeroom until 1917, when it was demolished and eventually Heal’s built on the same site. Apparently, Bloomsbury Square was established on the site of the Capper's cow field!

The original grid layout of Bloomsbury Square -

The original grid layout of Bloomsbury Square -originally called Southampton Square, the name was later changed.Bloomsbury Square was one of London's first designed garden squares. Originally it was known as Southampton Square, created to be in effect a large forecourt for Southampton House standing opposite. But the marriage of the Duke of Bedford to the Duke of Southampton's daughter, saw a name change to Bloomsbury Square. In the early 18th century the garden was merely a rectangular patch of grass with paths cutting across it. In the early 1800's, landscape designer Humphry Repton was commissioned to face-lift the gardens and created oval flower beds in each corner and a perimeter of lime trees.

Here I'm standing at the centre of Bloomsbury Gardens facing towards

Here I'm standing at the centre of Bloomsbury Gardens facing towardsSouthampton House.Prior to the World War II the gardens were enclosed by iron railings and only open to residents. As part of the war effort the railings were melted down for the manufacture of ammunitions, and in the 1950's the gardens officially opened to the public. In the 1970's an underground car park was built beneath the square and a new landscape scheme created which further lost Repton's design.

Statue of Charles James Fox at the corner of Bloomsbury Square

Statue of Charles James Fox at the corner of Bloomsbury SquareNovember 2013

The same statue of Charles James Fox in Victorian times

The same statue of Charles James Fox in Victorian timesPLEASE VOTE!

The cover of VERITY'S LIE has been nominated for an award.

I'd appreciate your support and it would be wonderful

if you could vote here.

http://www.indtale.com/polls/cr%C3%A9me-de-la-cover-contest-october-finals

Thank you

Grace XXXXX

Published on November 06, 2013 00:45

October 30, 2013

Historical Hauntings - the Tower of London

Photo courtesy of the Historic Royal Palaces

Photo courtesy of the Historic Royal PalacesJoin the ghostly fun on twitter with #TowerGhostThere’s no better time for a ghost story than Hallowe’en and no better place to tell them, than at the Tower of London. Over the centuries those ancient stone walls have witnessed murder, torture and imprisonment - and soaked up the distressed spirits of those who died there. Whether you believe in ghosts or not, there are compelling accounts, frequently by Yeoman Warders, of sights so terrifying that one witness even died of fright two days later. Of the ten ghostly apparitions associated with the Tower of London, here are my two favourites.

Portrait of a woman thought to be

Portrait of a woman thought to beMargaret Pole. Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury By all accounts Margaret Pole was a feisty character, but she needed to be with King Henry VIII as her enemies. Margaret was an unusual woman for a number of reasons: firstly, because she was a peeress in her own right (rather than being married to a nobleman) and secondly, because she reached the age of 70 – which was quite an achievement in Tudor England. However, Henry VIII was not a fan mainly because Margaret was a Plantagenet (a rival line of accession to England’s throne) and her son, Reginald, was a vocal critic of Henry’s religious and marital policies. Knowing Henry had charged him with treason Reginald fled abroad, but not so Margaret – who Henry arrested, put through a farcical trial and sentenced to death.

The Martin Tower at the Tower of London

The Martin Tower at the Tower of LondonFind out more at #TowerGhostsOn 27th May 1541, Margaret Pole was marched onto Tower Green at the Tower of London, where a crowd of 150 spectators had assembled to witness her execution. Margaret, however, was having none of it. She defiantly told the executioner that she refused to kneel at the block and if he wanted to cut her head off, he’d have to do it where she stood. You can almost feel sorry for the man – caught between a strident old woman and the orders of his king. In the end, the executioner took a swipe at Lady Pole, missed her neck and badly cut her shoulder. Bleeding heavily, Margaret's white hair stained red, she took to her heels and ran. Eventually, it took 11 blows to fell the countess in what was more butchery than execution.And so the story goes that on the anniversary of her death, May 27th, her ghost re-enacts her brutal end in a macabre dance around Tower Green....

Anne Boleyn

Queen Anne Boleyn

Another of Henry’s victims was his second wife, Queen Anne Boleyn. Once again Tower Green provides the backdrop for a grizzly scene with a French swordsman smiting Anne’s head from her shoulders on her husband’s command. Her body was removed, placed in an empty arrow chest for a coffin and buried beneath the floor in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. But it seems the lady lies uneasy for in Victorian times a Captain of the Guard noticed a light burning in the locked chapel. Suspicious of what was going on he placed a ladder against the chapel window to inside. What he saw is described in this excerpt from Ghostly London, London 1882.“Slowly down the aisle moved a stately procession of Knights and Ladies, attired in ancient costumes; and in front walked an elegant female whose face was averted from him, but whose figure greatly resembled the one he had seen in reputed portraits of Anne Boleyn. After having repeatedly paced the chapel, the entire procession together with the light disappeared.”

Anne Boleyn

Queen Anne Boleyn

Another of Henry’s victims was his second wife, Queen Anne Boleyn. Once again Tower Green provides the backdrop for a grizzly scene with a French swordsman smiting Anne’s head from her shoulders on her husband’s command. Her body was removed, placed in an empty arrow chest for a coffin and buried beneath the floor in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. But it seems the lady lies uneasy for in Victorian times a Captain of the Guard noticed a light burning in the locked chapel. Suspicious of what was going on he placed a ladder against the chapel window to inside. What he saw is described in this excerpt from Ghostly London, London 1882.“Slowly down the aisle moved a stately procession of Knights and Ladies, attired in ancient costumes; and in front walked an elegant female whose face was averted from him, but whose figure greatly resembled the one he had seen in reputed portraits of Anne Boleyn. After having repeatedly paced the chapel, the entire procession together with the light disappeared.”  The elegant memorial to those executed on Tower Green

The elegant memorial to those executed on Tower Green(author's own picture)In 1864 a sentry of the King's Royal Rifle Corps was patrolling the grounds when he came upon an misty apparition of a woman in Tudor dress, wearing a French hood – but lacking a face! He challenged her to stop but she kept advancing so he thrust at the figure with his bayonet. Apparently, as the bayonet passed through the mist he received an electric shock. The sentry was court-marshalled for sleeping whilst on duty – but a fellow officer came forward and said that whilst he was in the Bloody Tower, he heard the man shout out a challenge and was in time to witness the shadowy figure pass through the bayonet and then the guard himself!

Click for linkThose clever people at the Historic Royal Palaces have created a special hour long tour of ‘Ten Historical Hotspots’ within the Tower of London. If you are in London this Hallowe’en and want to find out more visit here: http://bit.ly/TowerGhosts

Click for linkThose clever people at the Historic Royal Palaces have created a special hour long tour of ‘Ten Historical Hotspots’ within the Tower of London. If you are in London this Hallowe’en and want to find out more visit here: http://bit.ly/TowerGhosts

This blog post is part of the Trick or Treat Hallowe'en Blog Hop.

This blog post is part of the Trick or Treat Hallowe'en Blog Hop.See links below for the participating blogs.

Published on October 30, 2013 08:35

October 23, 2013

18th Century Trivia - China, Glass and Silverware

Why do we call fine-pottery ‘china’?Which tax led to the development of ‘cut-glass’?

A beautiful example of a glass chandelier -

A beautiful example of a glass chandelier -

from the Assembly Rooms, Bath.

This weekend I had that most uplifting of experiences – finishing a manuscript, The Ringmaster’s Daughter, and sending it out to beta readers. Whilst awaiting their verdict I started researching #2 in this series of Georgian romances - which led me to find out some interesting trivia about dining in the early 18thcentury table settings. Let us start with George Ravenscroft and his invention of lead crystal (OK, the purists will argue this is a flawed statement. Apparently George didn’t ‘invent’ lead crystal but refined an already existing process to the point where it was usable. Also, the word ‘crystal’ is strictly incorrect, since the structure of the lead-glass is not crystalline in the scientifically accepted use of the term. But hey ho, it is what it is and I digress already) Examples of Ravenscroft glass - displayed at the V&A Museum.George Ravenscroft was an importer and exporter of fine goods who spent some of his career in Italy. Whilst there he observed Italian glass making techniques and decided it would make good business sense to recreate their fine crystal for the British market. On his return to England, he set up a workshop and was very secretive about his methods – presumably because he was afraid of imitation. It is unclear how he came to create his fine lead glass (or crystal ) and there were initial teething problems with crazing or ‘crizzling’ where fine cracks appeared with use, rendering the glass cloudy with time. But once the crizzling issue was resolved, Ravenscroft glass became extremely popular and very fashionable.

Examples of Ravenscroft glass - displayed at the V&A Museum.George Ravenscroft was an importer and exporter of fine goods who spent some of his career in Italy. Whilst there he observed Italian glass making techniques and decided it would make good business sense to recreate their fine crystal for the British market. On his return to England, he set up a workshop and was very secretive about his methods – presumably because he was afraid of imitation. It is unclear how he came to create his fine lead glass (or crystal ) and there were initial teething problems with crazing or ‘crizzling’ where fine cracks appeared with use, rendering the glass cloudy with time. But once the crizzling issue was resolved, Ravenscroft glass became extremely popular and very fashionable.

The addition of lead gave the glass a brighter, cleaner appearance which well suited Georgian tastes. The light scattering properties of Ravenscroft’s lead crystal made it ideal for chandeliers – and at a time when candles were the main light source for the wealthy – it was a match made in heaven. For the table Ravenscroft manufactured heavy, clear drinking glasses but when a glass was taxed in 1745, he reduced the weight by cutting deep jags and slices into the surface of the drinking vessels. This made them sparkle and shine even more when the light hit them – which became fashionable in its own right. When setting a table in the early 18th century, shimmer and shine were all the rage – and no more so than with eating utensils. The wealthy ate with silver cutlery – the forks laid prongs down so as not to catch in dangly lace cuffs and sleeves. Later, in the 1770’s, Thomas Bolsover developed the technique of silver plating base metals and the way was opened for the aspirational gentry to adorn their dinner tables with silverware. An example of a china tea pot - produced in England.

An example of a china tea pot - produced in England.

Early 18th century.The early 18th century also saw a great fad for china and porcelain. We derive the generic word ‘china’ from the thin porcelain imported as ballast in the hold of tea clippers. At this time tea was very expensive and highly desirable, but the taste was easily tainted in transit by the smell of other cargo. To this end the tea from China was packed in thin pottery, and in turn these pots became fashionable. In time, for each ton of tea imported, six tons of porcelain accompanied it as ballast. By 1723, over 5,000 teapots for 1 ½ d each, were imported – as compared to the cost of a (admittedly extensive) tea service in 1712, which was over £5.In the 1740’s a Chelsea factory began producing English bone china – beautifully painted and decorated – the like of which had not been seen before. A passion for china was born with the wealthy aspiring Meissen crockery from Germany and collecting tea-cups and ‘jacolite’ (chocolate) bowls from Italy. Indeed, Queen Anne decreed food must be:

‘…brought to the table on fair china plates.’

A beautiful example of a glass chandelier -

A beautiful example of a glass chandelier -from the Assembly Rooms, Bath.

This weekend I had that most uplifting of experiences – finishing a manuscript, The Ringmaster’s Daughter, and sending it out to beta readers. Whilst awaiting their verdict I started researching #2 in this series of Georgian romances - which led me to find out some interesting trivia about dining in the early 18thcentury table settings. Let us start with George Ravenscroft and his invention of lead crystal (OK, the purists will argue this is a flawed statement. Apparently George didn’t ‘invent’ lead crystal but refined an already existing process to the point where it was usable. Also, the word ‘crystal’ is strictly incorrect, since the structure of the lead-glass is not crystalline in the scientifically accepted use of the term. But hey ho, it is what it is and I digress already)

Examples of Ravenscroft glass - displayed at the V&A Museum.George Ravenscroft was an importer and exporter of fine goods who spent some of his career in Italy. Whilst there he observed Italian glass making techniques and decided it would make good business sense to recreate their fine crystal for the British market. On his return to England, he set up a workshop and was very secretive about his methods – presumably because he was afraid of imitation. It is unclear how he came to create his fine lead glass (or crystal ) and there were initial teething problems with crazing or ‘crizzling’ where fine cracks appeared with use, rendering the glass cloudy with time. But once the crizzling issue was resolved, Ravenscroft glass became extremely popular and very fashionable.

Examples of Ravenscroft glass - displayed at the V&A Museum.George Ravenscroft was an importer and exporter of fine goods who spent some of his career in Italy. Whilst there he observed Italian glass making techniques and decided it would make good business sense to recreate their fine crystal for the British market. On his return to England, he set up a workshop and was very secretive about his methods – presumably because he was afraid of imitation. It is unclear how he came to create his fine lead glass (or crystal ) and there were initial teething problems with crazing or ‘crizzling’ where fine cracks appeared with use, rendering the glass cloudy with time. But once the crizzling issue was resolved, Ravenscroft glass became extremely popular and very fashionable.

The addition of lead gave the glass a brighter, cleaner appearance which well suited Georgian tastes. The light scattering properties of Ravenscroft’s lead crystal made it ideal for chandeliers – and at a time when candles were the main light source for the wealthy – it was a match made in heaven. For the table Ravenscroft manufactured heavy, clear drinking glasses but when a glass was taxed in 1745, he reduced the weight by cutting deep jags and slices into the surface of the drinking vessels. This made them sparkle and shine even more when the light hit them – which became fashionable in its own right. When setting a table in the early 18th century, shimmer and shine were all the rage – and no more so than with eating utensils. The wealthy ate with silver cutlery – the forks laid prongs down so as not to catch in dangly lace cuffs and sleeves. Later, in the 1770’s, Thomas Bolsover developed the technique of silver plating base metals and the way was opened for the aspirational gentry to adorn their dinner tables with silverware.

An example of a china tea pot - produced in England.

An example of a china tea pot - produced in England.Early 18th century.The early 18th century also saw a great fad for china and porcelain. We derive the generic word ‘china’ from the thin porcelain imported as ballast in the hold of tea clippers. At this time tea was very expensive and highly desirable, but the taste was easily tainted in transit by the smell of other cargo. To this end the tea from China was packed in thin pottery, and in turn these pots became fashionable. In time, for each ton of tea imported, six tons of porcelain accompanied it as ballast. By 1723, over 5,000 teapots for 1 ½ d each, were imported – as compared to the cost of a (admittedly extensive) tea service in 1712, which was over £5.In the 1740’s a Chelsea factory began producing English bone china – beautifully painted and decorated – the like of which had not been seen before. A passion for china was born with the wealthy aspiring Meissen crockery from Germany and collecting tea-cups and ‘jacolite’ (chocolate) bowls from Italy. Indeed, Queen Anne decreed food must be:

‘…brought to the table on fair china plates.’

Published on October 23, 2013 00:28

October 16, 2013

Gardens Through the English Eras

I'm delighted to welcome Debra Brown to my blog. As well as writing the wonderfully evocative, The Companion of Lady Holmeshire, Debbie is the founder of the EHFA (English Historical Fiction Authors) of which I am proud to be a member. So without further ado - let me hand the stage to Debra.

Thumbing through my precious copy of the newly released Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, I came across an interesting contrast by author Judith Arnopp. She wrote: “Medieval literature depicts noblemen striding about the world, galloping into battle in the service of the king, embarking upon arduous pilgrimage and living and breathing upon a vastly dangerous, stimulating stage. These men are shown to be invincible, self-assured, and in control, and there were few limits placed upon them.“The women in this literature are portrayed very differently; they rarely travel, they never fight and are usually to be found within the vicinity of the castle walls. Their role is to marry, provide heirs, and be an asset to their husband. Life for most medieval woman was closeted; we see them safe within the walls of the castle, sewing, strumming musical instruments, listening to minstrels’ songs or to tales of courtly-love.”The favoured place for these activities was the garden, and many manuscripts illustrate this. We see women sitting among the flowerbeds, sometimes planting and maintaining the gardens or, more often, we find them in a lovers’ tryst. Other times they are shown sitting in the shade of a tree listening to a minstrel’s tales and, paradoxically, the stories they are listening to are of other women also dwelling within the safety of their own gardens.” A woodcut of a woman in a medieval kitchen gardenThough Judith’s lovely post goes on to discuss women and the garden as a literary device, at this point I was temporarily lost in the beauty of imagined gardens. This kind of beauty seems to be a part of us all—who doesn’t visit a garden from time to time or if given the time and resources, surround their home with greenery and colorful blooms?

A woodcut of a woman in a medieval kitchen gardenThough Judith’s lovely post goes on to discuss women and the garden as a literary device, at this point I was temporarily lost in the beauty of imagined gardens. This kind of beauty seems to be a part of us all—who doesn’t visit a garden from time to time or if given the time and resources, surround their home with greenery and colorful blooms?

If we could bring together persons from past centuries and ask them to draw a picture of “the typical garden”, what might they draw? Though of course at times and for many peoples the picture would be a muddy plot or a strip filled with common vegetables, herbs, or grain, M.M. Bennetts tells about the change in what an Elizabethan woman might sketch and why the difference. She tells us:

“…in 1520, the Church owned roughly one-sixth of the kingdom. By 1558, when Elizabeth ascended the throne—roughly twenty years after the Dissolution of the Monasteries—three-fourths of that land had been sold off, primarily into the hands of the gentry and the increasingly monied middle class. And this substantial change in land ownership brought with it equally substantial shifts in political, cultural, and economic power within the kingdom….“Translated into plain English, there was now a land-owning gentry and burgeoning middle class who found themselves able to spend more of their resources on pleasures and comforts, rather than on self-defence and necessities as they previously would have done.“So rather than the conversation between husband and wife going something like, ‘I see York is getting resty. I think we really should build another defensive tower and a moat...’ the conversation now could go something like, ‘Hmm, I fancy having a garden over on the south side of the house. With a rose pergola. What about you?’” A recreation of an Elizabethan Garden in the grounds of Kenilworth Castle

A recreation of an Elizabethan Garden in the grounds of Kenilworth Castle

Photo courtesy of English Heritage.And what did these Elizabethan gardens look like? M.M. describes them thus:

“Always the gardens of the period were walled or enclosed in some way—by walls, hedges, fences, or even moats—and generally built off the house, often accessible only from the family’s main room or parlour.“Enclosing the space ensured a measure of protection from wild animals (hungry deer) or thieves, but it also protected the plants from prevailing winds and provided a warmer microclimate. Then too, in plans of Elizabethan manor houses, one will occasionally find several unconnected walled gardens leading off from the different rooms in the house—some for pleasure, others for the medicinal herbs or vegetables, still others with their walls covered in espaliered apples, figs, and pear....“Also, Elizabethan gardens were always laid out formally, geometrically designed and as often as not symmetrically, with knot gardens being the most common feature of the late 16th century garden. Indeed, one could rightly call the knot garden a very English passion.”

What about the 17th Century woman who did not have the means for a defensive tower or moat to scrap? The average 17th Century housewife? Deborah Swift relates:

“The concept of a “pretty” garden would have been anathema to most women of the 17th century, as gardens were primarily about producing food and herbs, unless you were very wealthy, in which case the gardening was left to your servants. The 17th century author of The English Housewife, Gervase Markham, claimed the “complete woman” had:‘skill in physic, surgery, cookery, extraction of oils, banqueting stuff, ordering of great feasts, preserving of all sorts of wines…distillations, perfumes, ordering of wool, hemp and flax: making cloth and dying; the knowledge of dairies: office of malting; of oats…of brewing, baking, and all other things belonging to a household.’“Guess that did not leave much time for planting pretty flowers!” Deborah says. “Because kitchen gardens were about supplying the table, and as much ground as possible was covered with edible plants, every garden was different, planted according to the whims of the women of the household.”

M.M. Bennetts tells us:

“…with the onset of the Civil War in 1642 and the subsequent Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell, gardening, such as it had been, ground to a halt for many different reasons. Armies tramping across the countryside, particularly armies of Levellers, aren’t good for the preservation of gardens. Taxes were high and remained very high under Cromwell which meant substantially less disposable income….“With the Restoration of Charles II, the idea of a pleasure garden was once again permitted. But now, after their experience on the Continent, the large landowners and fashionable gardeners sought to recreate versions of the most splendid garden of their age: Versailles. And this formal style, full of grand canals, classical statuary, fountains, and extensive geometrical beds edged in box, held sway into the early years of the 18th century. A garden party at the time of King Charles II.

A garden party at the time of King Charles II.

“But vast, formal gardens are very expensive to maintain—they are not only labour intensive, they also take up so much land that might be otherwise profitably employed. And it was the garden writer and designer, Stephen Switzer, who suggested a cheaper alternative in his Ichnografia Rustica, published in 1718. He was writing mainly for the owners of villas—successful businessmen mostly—whose smallish estates were near London.“His proposal was that one should open up the countryside so that one might enjoy ‘the extensive charms of Nature, and the voluminous Tracts of a pleasant County...to retreat, and breathe the sweet and fragrant Air of gardens.’ He went on to suggest that the garden be ‘open to all View, to the unbounded Felicities of distant Prospect, and the expansive Volumes of Nature herself.’“Switzer examined costs and expenses; he proposed that the designs be more rural and natural and relaxed, that garden walls were an unnecessary expense, etc. In short, Switzer proposed the landscape movement which would transform the gardens of England….“… as the eighteenth century progressed, influenced by their experiences of the Grand Tour, by writers such as Pope and Walpole, and by visiting other gardens, England’s landed classes began to favour a less formal and more naturalistic approach to landscape design. In developing the uniquely English concept of the landscape garden, William Kent, Lancelot (‘Capability’) Brown, and the other great landscape architects of the period were responding to a complex assortment of social and aesthetic ideals among their clients.“As well as the integration of forestry, farming, and sport into the landscape, the ambition was in many respects to create an almost ‘natural’ appearance, where trees, water, open grassland, and carefully placed structures (bridges, temples, and monuments were popular) created a carefully balanced microcosm of the English countryside.” Capability Brown designed garden at Harewood House, nr Leeds.It is interesting to see how and why gardens changed over the centuries in these excerpts from various chapters. Castles, Customs, and Kings records much of life in changing Britain from Roman times through World War II. Battles, queens, fashions, and medicine are but a few of the topics covered. Tom Williams says of the book, “As an author who is unashamedly old-fashioned in my approach to historical writing, I rather enjoyed it. It did tell me things I didn't know and sparked an interest in some people and places I hadn't heard of before, but it is in no way a textbook. It's an amusing trot through British history and excellent bedtime reading….”

Capability Brown designed garden at Harewood House, nr Leeds.It is interesting to see how and why gardens changed over the centuries in these excerpts from various chapters. Castles, Customs, and Kings records much of life in changing Britain from Roman times through World War II. Battles, queens, fashions, and medicine are but a few of the topics covered. Tom Williams says of the book, “As an author who is unashamedly old-fashioned in my approach to historical writing, I rather enjoyed it. It did tell me things I didn't know and sparked an interest in some people and places I hadn't heard of before, but it is in no way a textbook. It's an amusing trot through British history and excellent bedtime reading….”

Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors is available at Amazon US, Amazon UK, and Kobo. It will soon be available at additional online bookstores.

Thank you so much Debra, for dipping into Castles, Customs and Kings in such an interesting way. And, dear reader, you might be interested to know that I have two pieces in the book!

Thumbing through my precious copy of the newly released Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors, I came across an interesting contrast by author Judith Arnopp. She wrote: “Medieval literature depicts noblemen striding about the world, galloping into battle in the service of the king, embarking upon arduous pilgrimage and living and breathing upon a vastly dangerous, stimulating stage. These men are shown to be invincible, self-assured, and in control, and there were few limits placed upon them.“The women in this literature are portrayed very differently; they rarely travel, they never fight and are usually to be found within the vicinity of the castle walls. Their role is to marry, provide heirs, and be an asset to their husband. Life for most medieval woman was closeted; we see them safe within the walls of the castle, sewing, strumming musical instruments, listening to minstrels’ songs or to tales of courtly-love.”The favoured place for these activities was the garden, and many manuscripts illustrate this. We see women sitting among the flowerbeds, sometimes planting and maintaining the gardens or, more often, we find them in a lovers’ tryst. Other times they are shown sitting in the shade of a tree listening to a minstrel’s tales and, paradoxically, the stories they are listening to are of other women also dwelling within the safety of their own gardens.”

A woodcut of a woman in a medieval kitchen gardenThough Judith’s lovely post goes on to discuss women and the garden as a literary device, at this point I was temporarily lost in the beauty of imagined gardens. This kind of beauty seems to be a part of us all—who doesn’t visit a garden from time to time or if given the time and resources, surround their home with greenery and colorful blooms?

A woodcut of a woman in a medieval kitchen gardenThough Judith’s lovely post goes on to discuss women and the garden as a literary device, at this point I was temporarily lost in the beauty of imagined gardens. This kind of beauty seems to be a part of us all—who doesn’t visit a garden from time to time or if given the time and resources, surround their home with greenery and colorful blooms?If we could bring together persons from past centuries and ask them to draw a picture of “the typical garden”, what might they draw? Though of course at times and for many peoples the picture would be a muddy plot or a strip filled with common vegetables, herbs, or grain, M.M. Bennetts tells about the change in what an Elizabethan woman might sketch and why the difference. She tells us:

“…in 1520, the Church owned roughly one-sixth of the kingdom. By 1558, when Elizabeth ascended the throne—roughly twenty years after the Dissolution of the Monasteries—three-fourths of that land had been sold off, primarily into the hands of the gentry and the increasingly monied middle class. And this substantial change in land ownership brought with it equally substantial shifts in political, cultural, and economic power within the kingdom….“Translated into plain English, there was now a land-owning gentry and burgeoning middle class who found themselves able to spend more of their resources on pleasures and comforts, rather than on self-defence and necessities as they previously would have done.“So rather than the conversation between husband and wife going something like, ‘I see York is getting resty. I think we really should build another defensive tower and a moat...’ the conversation now could go something like, ‘Hmm, I fancy having a garden over on the south side of the house. With a rose pergola. What about you?’”

A recreation of an Elizabethan Garden in the grounds of Kenilworth Castle

A recreation of an Elizabethan Garden in the grounds of Kenilworth CastlePhoto courtesy of English Heritage.And what did these Elizabethan gardens look like? M.M. describes them thus:

“Always the gardens of the period were walled or enclosed in some way—by walls, hedges, fences, or even moats—and generally built off the house, often accessible only from the family’s main room or parlour.“Enclosing the space ensured a measure of protection from wild animals (hungry deer) or thieves, but it also protected the plants from prevailing winds and provided a warmer microclimate. Then too, in plans of Elizabethan manor houses, one will occasionally find several unconnected walled gardens leading off from the different rooms in the house—some for pleasure, others for the medicinal herbs or vegetables, still others with their walls covered in espaliered apples, figs, and pear....“Also, Elizabethan gardens were always laid out formally, geometrically designed and as often as not symmetrically, with knot gardens being the most common feature of the late 16th century garden. Indeed, one could rightly call the knot garden a very English passion.”

What about the 17th Century woman who did not have the means for a defensive tower or moat to scrap? The average 17th Century housewife? Deborah Swift relates:

“The concept of a “pretty” garden would have been anathema to most women of the 17th century, as gardens were primarily about producing food and herbs, unless you were very wealthy, in which case the gardening was left to your servants. The 17th century author of The English Housewife, Gervase Markham, claimed the “complete woman” had:‘skill in physic, surgery, cookery, extraction of oils, banqueting stuff, ordering of great feasts, preserving of all sorts of wines…distillations, perfumes, ordering of wool, hemp and flax: making cloth and dying; the knowledge of dairies: office of malting; of oats…of brewing, baking, and all other things belonging to a household.’“Guess that did not leave much time for planting pretty flowers!” Deborah says. “Because kitchen gardens were about supplying the table, and as much ground as possible was covered with edible plants, every garden was different, planted according to the whims of the women of the household.”

M.M. Bennetts tells us:

“…with the onset of the Civil War in 1642 and the subsequent Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell, gardening, such as it had been, ground to a halt for many different reasons. Armies tramping across the countryside, particularly armies of Levellers, aren’t good for the preservation of gardens. Taxes were high and remained very high under Cromwell which meant substantially less disposable income….“With the Restoration of Charles II, the idea of a pleasure garden was once again permitted. But now, after their experience on the Continent, the large landowners and fashionable gardeners sought to recreate versions of the most splendid garden of their age: Versailles. And this formal style, full of grand canals, classical statuary, fountains, and extensive geometrical beds edged in box, held sway into the early years of the 18th century.

A garden party at the time of King Charles II.

A garden party at the time of King Charles II.

“But vast, formal gardens are very expensive to maintain—they are not only labour intensive, they also take up so much land that might be otherwise profitably employed. And it was the garden writer and designer, Stephen Switzer, who suggested a cheaper alternative in his Ichnografia Rustica, published in 1718. He was writing mainly for the owners of villas—successful businessmen mostly—whose smallish estates were near London.“His proposal was that one should open up the countryside so that one might enjoy ‘the extensive charms of Nature, and the voluminous Tracts of a pleasant County...to retreat, and breathe the sweet and fragrant Air of gardens.’ He went on to suggest that the garden be ‘open to all View, to the unbounded Felicities of distant Prospect, and the expansive Volumes of Nature herself.’“Switzer examined costs and expenses; he proposed that the designs be more rural and natural and relaxed, that garden walls were an unnecessary expense, etc. In short, Switzer proposed the landscape movement which would transform the gardens of England….“… as the eighteenth century progressed, influenced by their experiences of the Grand Tour, by writers such as Pope and Walpole, and by visiting other gardens, England’s landed classes began to favour a less formal and more naturalistic approach to landscape design. In developing the uniquely English concept of the landscape garden, William Kent, Lancelot (‘Capability’) Brown, and the other great landscape architects of the period were responding to a complex assortment of social and aesthetic ideals among their clients.“As well as the integration of forestry, farming, and sport into the landscape, the ambition was in many respects to create an almost ‘natural’ appearance, where trees, water, open grassland, and carefully placed structures (bridges, temples, and monuments were popular) created a carefully balanced microcosm of the English countryside.”

Capability Brown designed garden at Harewood House, nr Leeds.It is interesting to see how and why gardens changed over the centuries in these excerpts from various chapters. Castles, Customs, and Kings records much of life in changing Britain from Roman times through World War II. Battles, queens, fashions, and medicine are but a few of the topics covered. Tom Williams says of the book, “As an author who is unashamedly old-fashioned in my approach to historical writing, I rather enjoyed it. It did tell me things I didn't know and sparked an interest in some people and places I hadn't heard of before, but it is in no way a textbook. It's an amusing trot through British history and excellent bedtime reading….”

Capability Brown designed garden at Harewood House, nr Leeds.It is interesting to see how and why gardens changed over the centuries in these excerpts from various chapters. Castles, Customs, and Kings records much of life in changing Britain from Roman times through World War II. Battles, queens, fashions, and medicine are but a few of the topics covered. Tom Williams says of the book, “As an author who is unashamedly old-fashioned in my approach to historical writing, I rather enjoyed it. It did tell me things I didn't know and sparked an interest in some people and places I hadn't heard of before, but it is in no way a textbook. It's an amusing trot through British history and excellent bedtime reading….”

Castles, Customs, and Kings: True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors is available at Amazon US, Amazon UK, and Kobo. It will soon be available at additional online bookstores.

Thank you so much Debra, for dipping into Castles, Customs and Kings in such an interesting way. And, dear reader, you might be interested to know that I have two pieces in the book!

Published on October 16, 2013 00:15

October 9, 2013

Rabies in Georgian England

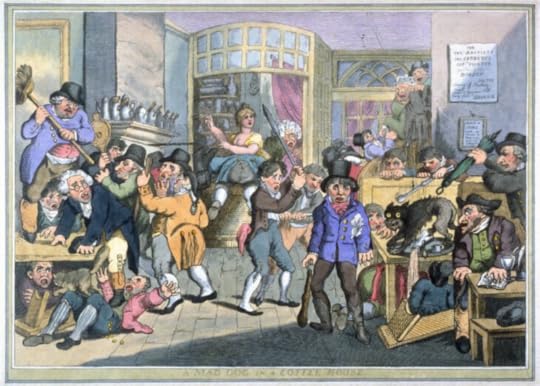

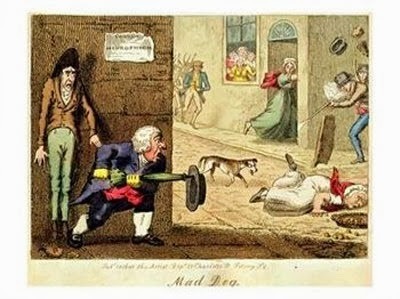

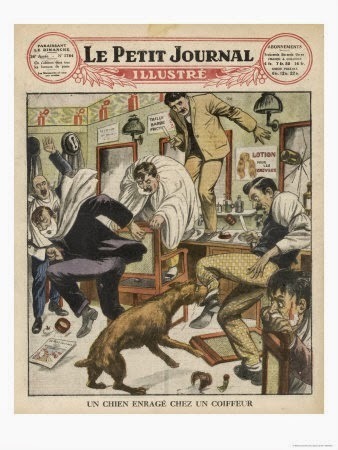

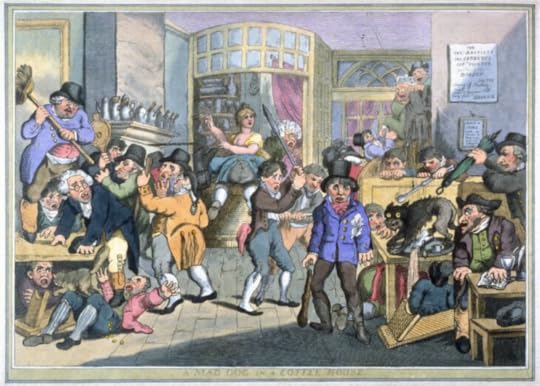

Thomas Rowlandson - A Mad-dog in a Coffee ShopThis week’s blog post was inspired by a cartoon by Thomas Rowlandson of a rabid dog in an 18th century coffee shop. It set me wondering how common rabies was in Georgian Britain…read on to find out.Rabies has been widespread throughout the world, including Britain, for many centuries. In Georgian times a notable outbreak occurred in Britain around 1734 - 5. Reports of rabid dogs went quiet for a while but then sadly escalated in 1752 when they penetrated St James’, in the heart of London. Orders were given to shoot dogs on sight.

Thomas Rowlandson - A Mad-dog in a Coffee ShopThis week’s blog post was inspired by a cartoon by Thomas Rowlandson of a rabid dog in an 18th century coffee shop. It set me wondering how common rabies was in Georgian Britain…read on to find out.Rabies has been widespread throughout the world, including Britain, for many centuries. In Georgian times a notable outbreak occurred in Britain around 1734 - 5. Reports of rabid dogs went quiet for a while but then sadly escalated in 1752 when they penetrated St James’, in the heart of London. Orders were given to shoot dogs on sight.

Seven years later, and events escalated again. A serious contagion occurred in London that took three years to bring under control. Owners were ordered to keep their pets indoors and a two shillings per head reward offered, to kill street dogs on sight. Unfortunately, this bounty triggered scenes of barbaric killing rather than being an effective method of disease control. By 1774 rabies had become generalised throughout England and paupers were discouraged from keeping dogs and a larger reward, of 5 shillings per head, offered for each stray killed. In 1793, a lone voice, Samuel Bardsley proposed a quarantine system ‘to eradicate rabies from the British Isles’.He suggested isolating dogs for a period of time to ensure they were free from disease, and the prohibition of imported of dogs until they had undergone a period of quarantine. The suggestion was ignored at the time but picked up again in 1851 by William Youatt who thought an appropriate quarantine period was eight months . Unfortunately, no one listened to Bardsley or Youatt and it was a century after the former’s suggestion was made, that the idea was put into practise.

During the 18th and 19th century rabies was endemic in the UK. Packs of semi-wild dogs formed the main reservoir of infection which crossed over into hunting dogs. One such outbreak amongst stag hounds meant the whole pack had to be destroyed. Rabies was at last brought under control when legislation was passed in 1867 and 1897 which enforced the humane shooting of strays, muzzling of pet dogs and strict quarantine of imported animals.

During the 18th and 19th century rabies was endemic in the UK. Packs of semi-wild dogs formed the main reservoir of infection which crossed over into hunting dogs. One such outbreak amongst stag hounds meant the whole pack had to be destroyed. Rabies was at last brought under control when legislation was passed in 1867 and 1897 which enforced the humane shooting of strays, muzzling of pet dogs and strict quarantine of imported animals.And finally, rabies put in another appearance in the UK, in 1918. Soldiers returned from the First World War smuggled pet dogs in from France and some of these dogs were incubating rabies. Fortunately the outbreak was limited and brought under control by 1922.

Published on October 09, 2013 01:15

October 2, 2013

A Tax on Dogs

Dc Johnson’s dictionary (1755) defined a pet as: “Any creature that is fondled or indulged”.

With thanks to 'One Cool Thing a Day'In 1796 a seemingly innocuous piece of tax legislation caused uproar in England. The new law provoked a debate about the very nature of the human spirit and whether owning a dog was a right or a luxury.At the end of the 18thcentury the English government was desperate for money to finance the on-going war with France. One way of raising the necessary cash was taxation. Tax was raised on everything from soap, to tea, tobacco, windows and lace – and indeed it didn’t stop there. Servants were a taxable asset under the auspices of the Male Servants’ Tax bill 1777- 1852 and the Female Servant’s Tax bill 1795 – 1852- but fortunately (or unfortunately?) wives and children were not taxable assets!. There was a Horse Tax (for owners of carriages and saddle horses), a Farm Horse Tax (for horses and mules used in trade) – but none of these taxes created quite the same stir as the imposition of the Dog Tax in 1796.

With thanks to 'One Cool Thing a Day'In 1796 a seemingly innocuous piece of tax legislation caused uproar in England. The new law provoked a debate about the very nature of the human spirit and whether owning a dog was a right or a luxury.At the end of the 18thcentury the English government was desperate for money to finance the on-going war with France. One way of raising the necessary cash was taxation. Tax was raised on everything from soap, to tea, tobacco, windows and lace – and indeed it didn’t stop there. Servants were a taxable asset under the auspices of the Male Servants’ Tax bill 1777- 1852 and the Female Servant’s Tax bill 1795 – 1852- but fortunately (or unfortunately?) wives and children were not taxable assets!. There was a Horse Tax (for owners of carriages and saddle horses), a Farm Horse Tax (for horses and mules used in trade) – but none of these taxes created quite the same stir as the imposition of the Dog Tax in 1796.

With thanks to LeFunny.net

With thanks to LeFunny.net

The crux of the disquiet lay in the very English relationship between man to dog. It raised a serious debate about whether a dog was a luxury or a natural part of being human. The tax tapped into questions about the emotional bond between the two. By putting a tax on dogs it implied a shift in relationship from one of nurturing and caring, to servility and subordination – and dog owners were enraged. To many this was tantamount to taxing spouses and children , and people weren’t happy. This wasn’t about the financial aspect of the tax, but the moral implication and feelings ran high. Those that supported the bill pointed out that pet dogs were a luxury, and consumed food that could have been better used to feed the poor. Opposers argued back that to need things beyond the essential – such as a dog – was a distinctly human trait. These people considered pets to be their friends, and putting a tax on them turned the language of friendship to that of slavery and service. With thanks to 'AnimalJam Wiki.'

With thanks to 'AnimalJam Wiki.'

Interestingly, the idea behind the dog tax may have originated in France (the very country the English needed to raise funds to fight!) In 1770 a French census suggested a population of four million dogs –an arthimetric extrapolation of the amount of food they consumed was equivalent to feeding a sixth of the population. The French dog tax was proposed to discourage dog ownership, as a means of disease control and to increase food availability.French authorities also insisted dogs belonging to the poor spread disease – especially rabies. This was considered a disease of dirty and hungry dogs, so poor labourers who – “Can scarcely feed themselves” should be discouraged from owning dogs by means of a tax. With thanks to 'TheMetaPicture.com'

With thanks to 'TheMetaPicture.com'

The difference between France and England was that in the former the tax remained as a proposition, whereas in the later it was acted upon. Whatever the moral argument the English government won in the end – the Dog Tax was imposed and stayed in place until 1882.So what do you think? Are dogs part of the family or a luxury - do leave a comment!

With thanks to 'One Cool Thing a Day'In 1796 a seemingly innocuous piece of tax legislation caused uproar in England. The new law provoked a debate about the very nature of the human spirit and whether owning a dog was a right or a luxury.At the end of the 18thcentury the English government was desperate for money to finance the on-going war with France. One way of raising the necessary cash was taxation. Tax was raised on everything from soap, to tea, tobacco, windows and lace – and indeed it didn’t stop there. Servants were a taxable asset under the auspices of the Male Servants’ Tax bill 1777- 1852 and the Female Servant’s Tax bill 1795 – 1852- but fortunately (or unfortunately?) wives and children were not taxable assets!. There was a Horse Tax (for owners of carriages and saddle horses), a Farm Horse Tax (for horses and mules used in trade) – but none of these taxes created quite the same stir as the imposition of the Dog Tax in 1796.

With thanks to 'One Cool Thing a Day'In 1796 a seemingly innocuous piece of tax legislation caused uproar in England. The new law provoked a debate about the very nature of the human spirit and whether owning a dog was a right or a luxury.At the end of the 18thcentury the English government was desperate for money to finance the on-going war with France. One way of raising the necessary cash was taxation. Tax was raised on everything from soap, to tea, tobacco, windows and lace – and indeed it didn’t stop there. Servants were a taxable asset under the auspices of the Male Servants’ Tax bill 1777- 1852 and the Female Servant’s Tax bill 1795 – 1852- but fortunately (or unfortunately?) wives and children were not taxable assets!. There was a Horse Tax (for owners of carriages and saddle horses), a Farm Horse Tax (for horses and mules used in trade) – but none of these taxes created quite the same stir as the imposition of the Dog Tax in 1796.  With thanks to LeFunny.net

With thanks to LeFunny.netThe crux of the disquiet lay in the very English relationship between man to dog. It raised a serious debate about whether a dog was a luxury or a natural part of being human. The tax tapped into questions about the emotional bond between the two. By putting a tax on dogs it implied a shift in relationship from one of nurturing and caring, to servility and subordination – and dog owners were enraged. To many this was tantamount to taxing spouses and children , and people weren’t happy. This wasn’t about the financial aspect of the tax, but the moral implication and feelings ran high. Those that supported the bill pointed out that pet dogs were a luxury, and consumed food that could have been better used to feed the poor. Opposers argued back that to need things beyond the essential – such as a dog – was a distinctly human trait. These people considered pets to be their friends, and putting a tax on them turned the language of friendship to that of slavery and service.

With thanks to 'AnimalJam Wiki.'

With thanks to 'AnimalJam Wiki.'Interestingly, the idea behind the dog tax may have originated in France (the very country the English needed to raise funds to fight!) In 1770 a French census suggested a population of four million dogs –an arthimetric extrapolation of the amount of food they consumed was equivalent to feeding a sixth of the population. The French dog tax was proposed to discourage dog ownership, as a means of disease control and to increase food availability.French authorities also insisted dogs belonging to the poor spread disease – especially rabies. This was considered a disease of dirty and hungry dogs, so poor labourers who – “Can scarcely feed themselves” should be discouraged from owning dogs by means of a tax.

With thanks to 'TheMetaPicture.com'

With thanks to 'TheMetaPicture.com'The difference between France and England was that in the former the tax remained as a proposition, whereas in the later it was acted upon. Whatever the moral argument the English government won in the end – the Dog Tax was imposed and stayed in place until 1882.So what do you think? Are dogs part of the family or a luxury - do leave a comment!

Published on October 02, 2013 00:59

September 22, 2013

Five Famous Occupants of Carisbrooke Castle

Click to find the other blogs taking part.My post is about Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight. One famous inhabitant was Charles I, imprisoned at Carisbrooke during the English Civil War – but can you name another four famous occupants? If not, read on…(in fact, even if you can –read on!)

Click to find the other blogs taking part.My post is about Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight. One famous inhabitant was Charles I, imprisoned at Carisbrooke during the English Civil War – but can you name another four famous occupants? If not, read on…(in fact, even if you can –read on!) PS GIVEWAY DETAILS AT THE END OF THIS POST!

Isabella de FortibusIn the 1260’s Isabella was one of the greatest landowners in England and that she was a woman made this all the more unusual. She came to her wealth through marriage and inheritance. The first by the death of her husband, William de Fortibus, when she was just 23. The second the murder of her brother, Baldwin de Redvers, who was possibly poisoned. When in 1262 she inherited his lands in the Devon, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, Isabella became extraordinarily wealthy and powerful.

Isabella's window in the present day

Isabella's window in the present day(Author's own photo) Isabella decided against marrying again and took up her brother’s lordship of the Isle of Wight to live at Carisbrooke Castle, new Newport, IOW. She used the castle as her main residence from which she oversaw the running of her southern estates. In addition she invested in improvements to the castle itself, adding expensive details such as a stunning window – the remains of which can be seen today as “Isabella’s window”. She reorded the principal apartments, built a chapel of St Peter, apartments for the constable, a new kitchen, a herb garden, a prison and a fish pond!

Sir George CareySir George Carey was the grandson of Mary Boleyn, (Anne Boleyn’s sister) , and therefore a cousin of Queen Elizabeth I. in 1583 he was appointed captain of the Isle of Wight –overseeing maritime law, controlling shipping around the island, and fighting piracy.

Sir George Carey Part of his work was to protect the island from invasion (see also: Invading the Isle ofWight). To do this he trained militia, fortified defences and refurbished the chain of beacons that would be lit as a warning should the Spanish invade.

Sir George Carey Part of his work was to protect the island from invasion (see also: Invading the Isle ofWight). To do this he trained militia, fortified defences and refurbished the chain of beacons that would be lit as a warning should the Spanish invade.  View from the ramparts of the ruin of Sir George Carey's house.

View from the ramparts of the ruin of Sir George Carey's house.(Author's own photo)In unsettled times, with the threat from Spain, the Isle of Wight would have given an invading navy a huge strategic advantage. With this in mind Carey fortified Carisbrooke Castle with the addition of small bastions, a large outwork and earthworks, in order to make the castle withstand a Spanish artillery attack. (Ultimately, the Spanish Armada arrived off the south coast in 1588, but sailed straight past the Isle of Wight)

Charles IFrom 22 November 1647 to 6 September 1648, Charles I was a prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle. During this time, the aim was for him to negotiate with Parliament and the Scots to find a settlement that would return some power to him. At first he was held as a guest, with considerable freedom and many luxuries – such as the bowling green created for on the eastern outwork (previous a drilling ground for militia). However, when no progress was made, his attendants were removed and he was imprisoned more strictly.

View from the ramparts of Charles I's bowling green (with the white marquee on it)

View from the ramparts of Charles I's bowling green (with the white marquee on it)(Author's own photo)

He continued to plot via secret messages carried by servants and on the night of 20 March 1648, Charles tried to escape. He climbed out of his bedchamber window but became stuck in the bars! After this he was removed to more secure quarters but even so, he plotted another escape but was thwarted when someone betrayed him and extra sentries were posted beneath his window.

The window through which Charles I tried to escape

The window through which Charles I tried to escape(Author's own photo)Eventually, Charles was moved to London and put on trial. He was executed in Whitehall on 30 January 1649.

Princess BeatriceQueen Victoria’s loved the Isle of Wight and bought Osborne House as a private family retreat.

Princess Beatrice with her mother, Queen Victoria.

Princess Beatrice with her mother, Queen Victoria.Her youngest daughter, Princess Beatrice seems to have inherited this love and spent the early part of her married life to Prince Henry of Battenburg, living at Osborne. Queen Victoria appointed Prince Henry as governor of the Isle of Wight, and when Henry died, Beatrice inherited this role.

The garden created by Princess Beatrice,

The garden created by Princess Beatrice,within the grounds of Carisbrooke Castle.

(Author's own photo.)

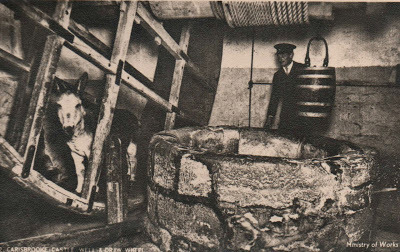

Some while later, in 1913, Princes Beatrice revived the lapsed custom that governors of the Isle of Wight resided in Carisbrooke Castle. She made some alterations, to bring it up to date, and spent many of her summer at Carisbrooke until her death in 1944.