Alan K. Rode's Blog

February 14, 2023

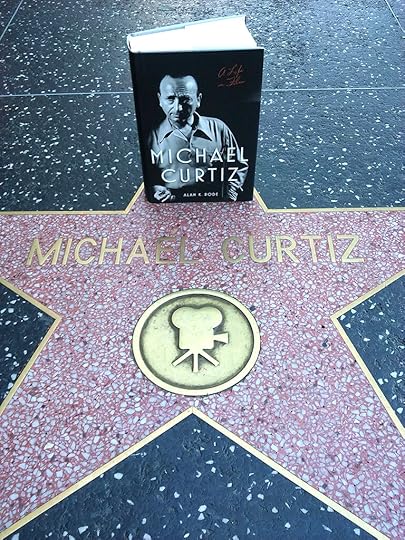

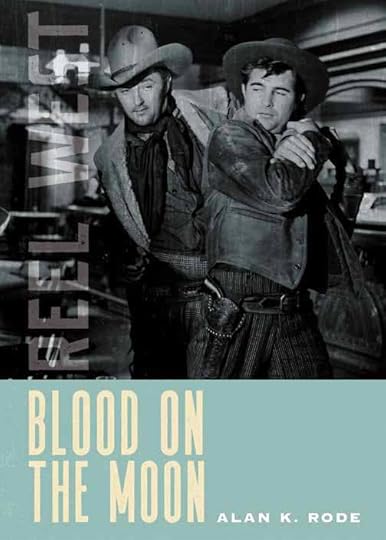

Blood on the Moon by Alan K. Rode

Of the movies categorized as “noir westerns” by writers and historians, none is more celebrated than 1948’s Blood on the Moon. The commingling of the Western genre and the noir style crystalized in this extraordinary film, which in turn influenced the development of the Western in the 1950s as the genre darkened and became more psychological. Produced during the height of the post–World War II film noir movement, the picture transplanted the dark urban environs of the city into the western iconography. Instead of being framed in a Monument Valley sunset, Robert Mitchum’s lone horseman opens the picture as a solitary figure in a dark rainstorm, with the Arizona trail replicating the rain-slicked streets of Los Angeles. Mitchum’s existentialist character Jim Garry plays against traditional Western heroes, with shifting loyalties set against an alienating domain where things are assuredly not what they seem.

Blood on the Moon is a classic Western immersed in the film noir netherworld of double crosses, government corruption, shabby barrooms, gun-toting goons, and romantic betrayals. With this volume, biographer and noir expert Alan K. Rode brings the film to life for a new generation of readers and film lovers.

Alan K. Rode is a charter director and the treasurer of the Film Noir Foundation, spearheading the preservation and restoration of America’s noir heritage. A documentarian and producer, he is also the author of Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film and Charles McGraw: Film Noir Tough Guy.

ISBN 978-0-8263-6469-2

REEL WEST

University of New Mexico Press | unmpress.com

“A first-rate look at an undervalued movie that represents a noted Western author (Luke Short), a talented screenwriter (Lillie Hayward), a director who was just coming into his own (Robert Wise), and a star on the ascendence (Robert Mitchum). Alan K. Rode gives us the story behind the story onscreen.”

Leonard Maltin

Author of Leonard Maltin’s Classic Movie Guide

October 3, 2022

Marsha Hunt, 1917-2022: An Appreciation of One of Hollywood’s Genuine Heroines

By Alan K. Rode

Marsha Hunt, 1917-2022: An Appreciation of One of Hollywood’s Genuine HeroinesFilm historian Alan K. Rode recalls his friendship with the actress who, beyond being one of the last great links to Hollywood’s golden age, dedicated herself to activism and service, forged in part by her experiences as a survivor of the Blacklist. Actress Marsha Hunt

Actress Marsha HuntThe death of actress-activist Marsha Hunt this week is a historical watershed and a personal loss. Marsha was one of the last living actors who began her movie career during the Great Depression in 1935. She became part of a now vanished Hollywood, initially at Paramount then at MGM, that bound contracted talent to studios with artists having little to no say over their choice of roles and careers. Nevertheless, she thrived in the studio system by becoming somewhat less than a genuine movie star and more of a consummate professional actress.

Marsha’s career was derailed by the Blacklist, a perfidious period of American history that has been endlessly chronicled and misunderstood. Never a Communist or radical, she was a forthright liberal who refused to accept her voice being marginalized by the endemic sexism and politics of the period. Marsha was the final survivor of the Committee of the First Amendment, an action group of film actors, directors and writers founded by screenwriter Philip Dunne, actress Myrna Loy, and directors John Huston and William Wyler. Members of the group flew to Washington D.C. on October 27, 1947 to protest the HUAC hearings investigating so-called subversive Communist influence in the motion picture industry. From a public relations perspective, the group’s involvement backfired and many people in the group subsequently had to seek political cover. After the pamphlet “Red Channels” was published in June 1950, naming Marsha and 150 other artists, journalists and writers by falsely portraying them as subversives who were manipulating the entertainment system, she had a great deal of trouble finding work in Hollywood.

Marsha told me she was presented with a loyalty oath that she was requested to sign in order to appear in “The Happy Time” in 1952, but was never was one to dwell on personal misfortune — Marsha was the original “using lemons to make lemonade” optimist about life. Instead, she preferred to recollect her husband in the film, the debonair Charles Boyer. “Every woman should have the opportunity to be married to Boyer even if it’s just in a movie,” she remembered with a smile.

There is a story about Marsha and the Blacklist I experienced first-hand. In 2007, my wife and I took Marsha to see “Trumbo,” a documentary about the great screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, written by his son Christopher, whom I knew. Of course, Marsha knew Dalton before and after he was blacklisted as one of the original Hollywood Ten who would be jailed for contempt of Congress. She also appeared in Trumbo’s movie adaptation of “Johnny Got His Gun” in 1971. Watching the movie and having Marsha point out where she was sitting and what she was thinking about at the time, as a newsreel clip of the HUAC hearing in the film showed her at the hearing in 1947, was akin to reliving history.

At one point, one of Trumbo’s letters was read about the fate of producer Adrian Scott. Scott had been married to actress Anne Shirley, who was one of Marsha’s best friends. The letter described Scott’s downfall due to being blacklisted: he was fired as a top producer at RKO, his marriage to Anne Shirley ended and he was now living alone in a small house in the Valley, grinding out TV scripts for “The Adventures of Robin Hood” under a pseudonym while sitting in a chair with his typewriter balanced on a milk crate and only a photo of Franklin Roosevelt adorning the bare walls of his house. Marsha moaned audibly and put her hand over her heart. When I asked if she was all right, she nodded and said, “You know I wasn’t really politically astute at that time, but I knew Adrian so well and admired him tremendously. I thought he was one of the finest men I ever met, so if he was for something, I knew it was the right thing to do.”

Marsha Hunt (Courtesy Alan K. Rode)

Marsha Hunt (Courtesy Alan K. Rode)Doing the right thing was Marsha’s credo, and there was never anything phony or self-serving about it. Her incredibly long and fulfilling life simply can’t be detailed here — I heartily recommend Roger Memos’ celluloid valentine “Marsha Hunt’s Sweet Adversity” (2015) for a complete overview of Marsha’s life and career. From her work at SAG and the United Nations, to helping the homeless as the ceremonial mayor of Sherman Oaks, to her beautiful table book centered on fashion, “The Way We Wore,” Marsha talked the talk and walked the walk.

On the personal side: Marsha and I met previously several times, but we became close after I invited her to be the special guest at the Noir City Film Festival at San Francisco’s Castro Theater. After being interviewed by Eddie Muller and charming the audience, Marsha could have been elected as mayor of San Francisco, hands down. My wife Jemma and I acted as Marsha’s escort — she was a youthful 89 at the time — and the three of us drew close with meals and screenings and being together talking about everything. Marsha signed a Noir City poster for me with the inscription, “To Alan, my White Knight of Noir City.” I was hooked.

Marsha Hunt and Raymond Burr in “Raw Deal” (1948)

Marsha Hunt and Raymond Burr in “Raw Deal” (1948)There were so many wonderful memories accrued during parties at Marsha’s house, dinners out, screenings in Hollywood, helping her select her wardrobe for Eddie Muller’s short film “The Grand Inquisitor,” appearances by her at Noir City in Hollywood and my annual film festival in Palm Springs. Marsha was one of the first people we invited over after we settled in our current house. While she sampled some of Jemma’s cuisine, Jake, our energetic cat, climbed up the back of her chair and perched on her shoulder. Marsha, forever composed, looked up calmly and questioned. “Alan dear. Is he supposed to be doing that?”

Being with Marsha was empowering; Her unwavering optimism might have seemed naïve to some, but it was infectious. I remember telling her, half-seriously, that after an evening together at her favorite Indian restaurant in North Hollywood, I was motivated to take on a massive project to do something good, something mildly ambitious like trying to end world hunger — an issue Marsha herself was involved in with her work with the U.N. and with the homeless in Sherman Oaks. Spending time with her enabled me to grow as a person. Marsha met a countless number of people during her life and I believe she had a positive influence on every one of them. Her stories of Hollywood and the great and near-great were legion and often spontaneous. “I’ve told you about the time Orson and I went to see Eartha Kitt do her cabaret act when I was in London, didn’t I?” was a typical opening. Another time while I was sitting at her piano, fingering the keys, she mentioned that her late husband, screenwriter Robert Presnell Jr., had a friend named “Leonard” who played some of the music he was composing for a film on her piano. Further inquiry revealed it was Leonard Bernstein, who was trying out a music cue from his “On the Waterfront” score on Marsha’s piano. I looked at my fingers touching the keys and blithely wondered if I should ever wash my hands again.

One of my most cherished memories of Marsha occurred during an evening when I hosted a Glenn Ford double bill at the Egyptian Theater for the launch of Peter Ford’s biography on his father. The theater was full, and many of the survivors of Old Hollywood were present. I was still getting my feet under me as far as being in front of an audience and was a bit nervous. But the show went well and afterwards Marsha and I were sitting in the lobby. Suddenly she looked directly at me and put her hands on my face saying, “Alan, I’m so proud of you. You were really superb. You can do this!” Marsha provided some unsolicited and genuine professional affirmation at a time when I needed it.

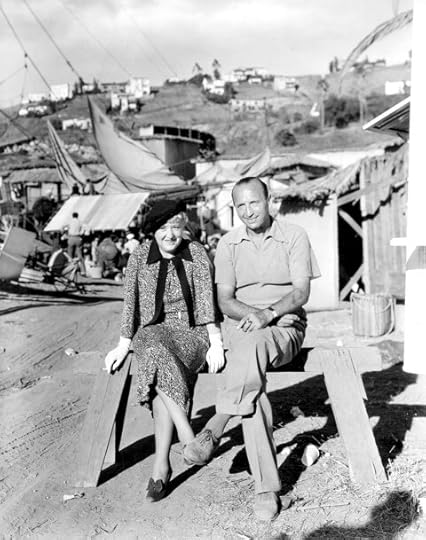

Marsha Hunt and Alan K. Rode

Marsha Hunt and Alan K. RodeWhile the page has now turned on so much of Marsha’s history — the golden age of Hollywood; the Blacklist; the United Nations when it was universally viewed as an entity for good — what I will always remember is her selflessness and intelligence with the sincerest interest and empathy for others. Most of all, I’ll always cherish our friendship. There is special place in the firmament for Marsha Hunt; she is forever a shining star.

Noted film historian Alan K. Rode is the author of “Michael Curtiz, A Life in Film,” among other books. He is the director-treasurer of the Film Noir Foundation and the host and producer of the annual Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival in Palm Springs.

December 31, 2021

Being the Ricardos

While watching Being the Ricardos, I recalled a remark by the screenwriter Julius Epstein about his best remembered movie Casablanca (1943). Epstein, who wrote the film with his twin brother Philip and Howard E. Koch, referred to Casablanca as “slick shit.” Meaning that the picture eventually regarded as nonpareil cinema struck him as a fantasia that bore little resemblance to either actual world events or contemporary human behavior, but nonetheless was compelling entertainment.

I experienced a similar sentiment about Being the Ricardos. Lucille Ball’s career, teetering the precipice of a Red Scare era smear while she was pregnant and co-starring with her husband Desi Arnaz in I Love Lucy (the number one TV show in 1953), is shoehorned into a week of rehearsals, climaxing with the filming of the program and Lucy’s exoneration. It is a signature instance of effective story construction buttressed by intermittent flashbacks featuring the older characters of writers Bob Carroll (Ronny Cox), Madelyn Pugh (Linda Laven) and producer Jess Oppenheimer (John Rubinstein) discussing the circumstances and principals many years later.

Nicole Kidman’s performance of Lucille Ball is analogous to attempting to scale Mount Everest wearing shower shoes. Kidman is game and tries hard; her voice approximates that of Ball and many of her dramatic scenes possess genuine heft. But when she is shown in clips of I Love Lucy or relentlessly pursuing comedic perfection during show rehearsals, her turn doesn’t ring true. She comes across as gaunt, grim and unamusing. The dearth of humorous lift rests with Aaron Sorkin who was widely quoted as saying I Love Lucy is no longer funny—an admission of comedic cluelessness by the writer-director who understands how the legendary show was put together but not why it clicked with millions and became a classic continuing to be rerun around the world.

The rest of the cast is close to flawless. Javier Bardem is a superb actor; he literally becomes Desi Arnaz. Ditto for the great J.K. Simmons as a curmudgeonly William Frawley, Nina Arianda as Vivien Vance, Tony Hale as producer Jess Oppenheimer, Jake Lacy as an overly whining version of writer Bob Carroll and the appealing Alia Shawkat as writer Madelyn Pugh.

People of my age and background are often troubled by contemporary filmmakers being cavalier with the sequencing and accuracy of historical events. Most notable of this type of gaffe in Becoming the Ricardos is the invented conversation between then head of RKO Pictures Charles Koerner and Lucy with the latter referencing Judy Holliday (who didn’t make her screen debut until six years later) as getting choice parts that should have gone to her. There are also liberties taken with recounting of different events such as J. Edgar Hoover’s clearance of Ball. This type of pretzel twisting has been ongoing since DeMille’s barn was built and while it can be indicative of historical laziness, I tend to default to Alfred Hitchcock response to Farley Granger’s objection about some unrealistic aspect of Strangers on a Train— “Farley, it’s only a movie!”

What I found specifically objectionable was the running time and several attributes of Sorkin’s screenplay. At slightly over two hours, Becoming the Ricardos is overlong—90 to 105 minutes would have made for a more cogent picture. I had a similar, but more demonstrative gripe with the recent remake of Nightmare Alley which weighed in at two hours and twenty minutes, an excessive duration for a screen adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s dark carnival story. For all of his flaws, the chief virtue of a Darryl F. Zanuck was providing adult supervision by injecting editing discipline into a script, a director and rough cut. Alas, there are no more studio executives who appear to have any sense or conviction about a movie being any good unless it is based on a comic book character.

Aaron Sorkin’s dialogue, particularly in the first 30 minutes, ranges from pithily clever to self-indulgent. While listening to Kidman and Bardem volley rapid fire bon mots back and forth, I wasn’t entirely sure whether Sorkin was adapting His Girl Friday or if Lucy and Desi were appearing in a remake of Sweet Smell of Success. Most of it is quite enjoyable even if people didn’t speak in that manner, then or now.

There is also the infiltration of current culture mores and language into a period piece. In addition to the now-tiresome overuse of the “F” word which was assuredly not a routine part of the lexicon in 1953, would Jess Oppenheimer call himself a “show runner”? Would Madelyn Pugh have made an impassioned speech to Lucy claiming she was preventing the star from being “infantilized”? Worse yet was Lucy accusing Desi of “gaslighting” her. And forgive me, but I simply could not picture Lucy knocking back a neat Jim Beam while unburdening herself personally to crotchety Bill Frawley at Boardner’s bar in Hollywood.

Criticisms aside, Becoming the Ricardos facilely depicts how Lucille Ball bailed from a fading movie career (her film resume was not as desultory as indicated) and reinvented herself as a comedic television star who became an American icon. She was able to pull this off in large part due to her partnership with a brilliant husband who was much more than her comedic foil. Desi Arnaz was an exceptional executive who bought RKO ‘s studio facilities and was the guiding hand of Desilu before the years of booze and bimbos caught up with him. What impressed me is how Aaron Sorkin melded numerous true events into a dramatic story. Becoming the Ricardos might be inaccurate history but it is artfully designed entertainment.

September 15, 2021

Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival 2021 – Schedule

Tickets and All Access Passes available now! https://arthurlyonsfilmnoir.ning.com/

Thursday October 21: 7:30 PM

WHERE THE SIDEWALK ENDS (1950) Disney-Fox, 95 min. Dana Andrews gives one of his most memorable performances as a troubled New York police detective whose heavy handedness jeopardizes both his career and the woman (Gene Tierney) he loves. Ben Hecht’s crackling script, based on the novel Night Cry by Victor Trivas, is the foundation for a much darker reunion of Andrews, Tierney, director of photography Joseph La Shelle and director Otto Preminger from Laura six years earlier.

Scheduled special guest: Susan Andrews, daughter of Dana Andrews

Friday October 22

10:00 AM: NIGHT HAS A THOUSAND EYES (1948) Universal; 81 min. Edward G. Robinson stars as a phony carnival mentalist who suddenly becomes imbued with the ability to actually predict the future – and he foresees a horrific fate for his best friend’s daughter. Barre Lyndon and Jonathan Latimer’s seamless adaptation of Cornell Woolrich’s novel is faultlessly directed by John Farrow (The Big Clock, Alias Nick Beal, As Danger Lives, His Kind of Woman) who was at his best with noir. Costarring Gail Russell and John Lund, with superbly shaded camerawork by John F. Seitz. Watch for Angels Flight in LA’s Bunker Hill!

1:00 PM: THE BIG SLEEP (1946) WB, 116 min. Director Howard Hawks helmed the ultimate screen pairing of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in this classic rendition of Raymond Chandler’s famed novel as adapted for the screen by William Faulkner, Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett. Don’t try to figure out the plot—just savor Bogie as private eye Philip Marlowe who fends off amorous dames (Martha Vickers, Dorothy Malone) while taking on gangsters and gunsels (John Ridgely and Bob Steele) and finding his true north with Bacall whom he married after the film originally wrapped and shot retakes with later as man and wife. Memorable score by the great Max Steiner.

Introduction with author Steven C. Smith, Music by Max Steiner, The Epic Life of Hollywood’s Most Influential Composer.

4:00 PM: EL VAMPIRO NEGRO (The Black Vampire) (1953), 90 min., subtitled. Not on streaming, DVD or Blu-ray. This rediscovered Argentinian film is a pro-feminist version of Fritz Lang’s M that was restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive with funding by the Film Noir Foundation in 2014. Filmed on location in the streets and sewers of Bueno Aires by director Román Viñoly Barreto, this haunting film stars Olga Zubarry as a heroic cabaret singer attempting to save her child from the clutches of a pedophile murderer (memorably played by comic actor Nathán Pinzón) while resisting the advances of a dedicated, but troubled prosecutor (Roberto Escalada). Beautifully written, filmed and scored; a memorable cinematic experience!

7:00 PM QUAI DES ORVERES (Jenny Lamour) (1947) Janus Films, 106 min. subtitled. Director/writer Henri Georges Clouzot (Le Corbeau, The Wages of Fear, Diabolique) reclaimed his reputation and won the Best Director Prize at the Venice Film Festival with one of France’s most enduringly popular films. Jenny Lamour (Suzy Delair) is a flirtatious music hall entertainer who persuades a wealthy, horndog patron Brignon (Charles Dullin) to fund her career, driving her devoted and jealous husband Maurice (Bernard Blier) round the bend. When Brignon turns up dead, Maurice looks like the culprit as crusty Inspector Antoine (Louis Jouvet) investigates. A memorable look at the post World War II Parisian dance hall world amidst a darkly poignant story.

Saturday October 23

10:00 am: THE CRUEL TOWER (1956) Allied Artists/Paramount, 79 min.

Not on Streaming, DVD or Blu-ray. In the finest tradition of Arthur Lyons, here is a lurid, noir-stained melodrama directed by Poverty Row auteur Lew Landers. A singularly dyspeptic Charles McGraw honchos a group of steeplejacks (Alan Hale Jr., Steve Brodie and Peter Whitney) who get thrown off kilter by an iterant drifter (John Ericson) and the statuesque Mari Blanchard. Murder, lust, rivalry and overlapping double crosses churn through this campy, low budget film like a high speed blender!

11:30 am: Book Signing with Eddie Muller (Dark City, revised & expanded edition), Steven C. Smith (Max Steiner the Epic Life of Hollywood’s Most Influential Composer) and Alan K. Rode (Michael Curtiz A Life in Film revised and expanded paperback edition).

1:00 pm: ANGELS WITH DIRTY FACES (1938) Warner Bros. 97 min.

Long missing from theaters and television, this proto-noir classic that consecrated James Cagney as Hollywood’s most timeless gangster makes its return to the big screen! As Rocky Sullivan, Cagney travels the well-worn cinematic path from reform school to gangsterism and state prison. He returns to his old NYC neighborhood to meet up with his boyhood pal who is now a priest (Pat O’Brien), the girl he used to tease (Ann Sheridan) and a group of young hoodlums (the Dead End Kids) who idolize him. When Rocky’s crooked lawyer (Humphrey Bogart) and crime boss Mac Keefer (George Bancroft) attempt to double cross him and O’Brien launches a reform campaign, the sparks start flying! Memorable direction by Michael Curtiz with a rousing score by Max Steiner.

4:00 pm: HIGH WALL (1947) MGM/Warner Bros., 99 min, 35mm. Brain-damaged veteran Robert Taylor confesses to murdering his unfaithful wife and is committed to a state sanitarium. While undergoing treatment, his doctor (Audrey Totter) begins to believe he may not be guilty of the crime. Director Curtis Bernhardt elicits one of Taylor’s best screen performances by using a post WWII film noir trope of combat induced amnesia as a central plot point. With: Herbert Marshall, Dorothy Patrick and H.B. Warner. Watch for a gem of a bit part by Frank Jenks.

7:00 pm: VIOLENT SATURDAY (1955) Disney-Fox, 90 min. Color, CinemaScope. Three hoods (a Benzedrine inhaling Lee Marvin, J. Carrol Naish and Stephen McNally) plan a weekend robbery of a bank in small Southwestern mining town that turns out to be film noir’s version of Peyton Place. The mine manager (Victor Mature) tries to have his son not to be ashamed of him, the librarian (Sylvia Sydney) becomes a thief, a bank manager (Tommy Noonan) enjoys nocturnal window peeping while a man (Richard Egan) wants his wife (Margaret Hayes) to stop fooling around with a golf pro (Brad Dexter). Add in Ernest Borgnine as an Amish farmer who encounters the robbers and you’ve got one hell of a weekend! Expertly directed by Richard Fleischer on location in Bisbee and Tucson, Arizona. Adapted from William Heath’s novel.

Scheduled special guest, producer Mark Fleischer, son of director Richard Fleischer.

Sunday October 24

10:00 am: Not on Streaming, DVD or Blu-ray. PLAYGIRL (1954) Universal, 85 min. A New York chanteuse (Shelley Winters) attempts to wise up her corn-fed friend (Coleen Miller) to the realities of city life but matters quickly spiral out of control. Shelley’s neighbor (Gregg Palmer) works for a scandal rag and her playboy friend (Richard Long) is little more than a pimp. Meanwhile, Winters warbles on the bandstand between trysts with her married boyfriend (Barry Sullivan). This lurid Joe Pevney-helmed melodrama was vaulted for over half a century. Don’t miss an unbound Shelley!

1:00 pm: THE LONG HAUL (1957), Sony-Columbia, 100 min. Harry Miller (Victor Mature), an American GI married to a British war bride (Gene Anderson), signs on as a long-haul lorry driver and finds the business rife with corruption, especially with gangster Joe Easy (Patrick Allen) running the show. When Easy’s girl Lynn (Diana Dors) takes a shine to Harry, his sturdy moral fiber is stretched every which way but loose. A well-wrought British version of Hollywood trucking noirs like THEY DRIVE BY NIGHT and THIEVES’ HIGHWAY, this film satisfies the craving of noir addicts with its underworld misfits, shadowy atmospherics and the voluptuous Dors doing all she can to screw up Mature’s marriage. With a thrilling climax reminiscent of SORCERER!

Introduction with Victoria Mature, daughter of Victor Mature.

4:00 PM: THE RECKLESS MOMENT (1949) Paramount, 82 min.

California matron Joan Bennett takes charge of her Balboa beachside household with hubby out of town, but can’t convince her smitten daughter (Geraldine Brooks) to dump her rake of a boyfriend (Sheppard Strudwick). After events spiral out of control, Bennett struggles to cover up an accidental death as a stranger (James Mason) arrives with incriminating evidence. Max Ophuls masterfully sequences a myriad of emotions, characterizations and plot points into a stone masterpiece of a film noir. Not to be missed! 35mm print courtesy of Sony-Columbia.

Tickets and All Access Passes available now! https://arthurlyonsfilmnoir.ning.com/

August 6, 2020

Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film – Q&A – American Cinematheque Event 2aug2020

Here are the remaining questions submitted during the American Cinematheque book club Zoom presentation on Sunday August 2nd, 2020 — with my responses.

So sorry we didn’t have time to get to everyone’s questions but I hope this helps. Thanks again for tuning in!

Q & A– What was the most interesting fact you found out about Curtiz when you were doing research for the book?

AKR: This question provides a wide meadow for exercise but for the sake of brevity, I think it was discovering what an artistically creative man Michael Curtiz was.

I found much of what had been written about him previously was steeped in anecdote and auteur system dogma.

– What were Curtiz’s feelings on Ronald Reagan?

AKR: There is nothing specific. Reagan appeared in two Curtiz pictures: SANTA FE TRAIL (1940) and THIS IS THE ARMY(1943). Curtiz probably regarded Reagan for what he was at that time: a competent second tier leading man at Warner Bros.

Most of Reagan’s writing about Curtiz in his memoir Where’s the Rest of Me concerns a well-chronicled anecdote about Curtiz’s reaction to an actor who fell off a platform during the SANTA FE TRAIL production.

This story varied depending on who—Reagan, James Cagney and Raymond Massey— was relating the tale. Reagan’s written recollections about SANTA FE TRAIL mostly centered on Errol Flynn.

THIS IS THE ARMY(1943) was a huge Irving Berlin musical revue with Reagan playing a key role as George Murphy’s son (!). It was Curtiz’s most profitable film during his three decades at Warner Bros.

– How much of THE COMANCHEROS did John Wayne direct? Was Curtiz off set, in the hospital during that time?

AKR: Curtiz was dying during the production of THE COMMANCHEROS. He fell on location in Utah, hurt his leg and either immediately returned to L.A. for treatment or was x-rayed on site and then returned home.

He was discovered to be riddled with cancer. John Wayne directed the rest of the picture. Probably 50-60 percent of THE COMMANCHEROS was directed by Wayne.

– Netflix has a Curtiz biopic. Have you seen it, were you involved with it and do you recommend it?

AKR: I was asked to review and mark up the script of this film, but declined to do so when the filmmakers said they couldn’t pay me.

I was then asked to provide some written answers to general questions about Curtiz as a courtesy, which I did and for which the filmmakers gave me a “thank you” credit.

I cannot recommend this film as it portrays the production of CASABLANCA and the characters of Curtiz, Hal Wallis, Jack Warner, the Epstein brothers, S.Z. Sakall, his daughter Kitty, Bess Meredith et al in a fictional story line that is absurd and patently false.

– What was Michael Curtiz’ relationships with James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart & John Garfield?

AKR: Cagney respected Curtiz more than any other director at Warner Bros. but disapproved of his often demeaning treatment of non-star actors.

Bogart felt likewise and thought Curtiz spent more attention on the camera than the actors. He argued with Curtiz about the CASABLANCA ending and during PASSAGE TO MARSEILLE, a film that apparently nobody enjoyed making.

Garfield liked Curtiz enormously and had a collaborative relationship with him, particularly during THE BREAKING POINT.

– I was thinking about the wide variety of genres Curtiz directed. How did he get to direct something as

seemingly sentimental as FOUR DAUGHTERS?

AKR: Curtiz made FOUR DAUGHTERS because it was assigned to him. He wasn’t able to pick his own pictures although by 1938, he had acquired more power with all of the success he’d had since CAPTAIN BLOOD (1935).

Curtiz was drawn to the sentimentally of the material—despite his bluster, he was a very sentimental man—and he selected John Garfield whom he immediately recognized as an extraordinary talent.

Garfield was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for FOUR DAUGHTERS as was Curtiz for Best Director, the Epstein bros. and Lenore Coffee for Best Writing, Nathan Levinson for Best Sound and the film was nominated for Best Picture.

– Did Curtiz use the same techniques for his flood in NOAH’S ARK as Cecil B DeMille used in THE TEN COMMANDMENTS?

AKR: The flooding scenes in NOAH’S ARK and THE TEN COMMANDMENTS are similar only in that they both used actual water from dump tanks. DeMille created the illusion of the Red Sea parting by filming large dump tanks pouring water into a catch basin (now a parking lot on the Paramount lot) then the film was shown in reverse. The two frothing walls of water were created by water dumped constantly into the catch basin areas, then the foaming, churning water was visually manipulated and used sideways for the walls of water. Gelatin was added to the tanks to give the water a consistency like sea water. Curtiz used a similar process for his Red Sea parting sequence in THE MOON OF ISRAEL (1924) that I describe in the book. For the NOAH’S ARK debacle, here is an abbreviated account adapted from my book: https://alankrode.com/hollywoods-great-deluge/

– How do you think Curtiz would respond if you asked him ‘what is film noir and does it have any influence on your movies?

“Vat is Feelm Noir?” If Curtiz was asked this question, he probably would have responded in the same manner that Billy Wilder did when he said filmmakers during the 1940s and 50s had no idea what film noir was when they were making movies like ACE IN THE HOLE, SUNSET BOULEVARD, MILDRED PIERCE and THE BREAKING POINT.

I think if the film noir style was explained to Curtiz, he would have instantly grasped and expounded upon it.

September 6, 2019

THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE (1936): Separating Fact from Fiction

Over the years, there have been numerous stories published or otherwise repeated about the production of Warner Bros.’ action film, THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE (1936).

These anecdotal accounts received additional heft in 1975 with the publication of David Niven’s memoir BRING ON THE EMPTY HORSES.

Among other recollections, Niven wrote about director Michael Curtiz’s “carnage” of injured and dead horses caused by his ordering the use of a “Running W” or trip wire during action scenes that were supposedly filmed in Mexico.

Other versions included a fight between Errol Flynn and Curtiz that never occurred (There was a physical confrontation between both men that occurred six years later during DIVE BOMBER) reportedly caused by Flynn’s rage over the director’s alleged indifference to the welfare of animals with the number of horses crippled or killed during the making of the picture ranging from 20 to 100 or many more.

My research, based on studio production records, correspondence and legal files( including sworn affidavits and photographs) and other sources, revealed an accurate and less fabulist account of what occurred during production of the film.

What follows is a partial synopsis of my chapter The Reason Why from Michael Curtiz, A Life in Film©. All copyright protections will be enforced.

THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE (1936): Separating Fact from FictionDirector Michael Curtiz pitched in with even greater alacrity than usual after being assigned to shoot the opening sequence of Anthony Adverse. He was attempting to convince Hal Wallis to let him direct the forthcoming epic `. Based on a poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and eventually titled The Charge of the Light Brigade, the picture was designed as a follow-on vehicle for Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland to emulate Warner’s smashing success of Captain Blood.

The script for Light Brigade by Rowland Leigh and Michel Jacoby was historically ludicrous even by Hollywood standards. The famous charge at the climax of the Crimean War was linked to the British 27th Lancers regiment stationed in India, which was seeking revenge against Amir Surat Khan of Suristan in northwest India, who allied himself with Imperial Russia and slaughtered the British garrison at Chukoti, including the regiment’s dependents. A revenge-obsessed Geoffrey Vickers (Flynn) discovers that the Amir has fled India and is at the Russian lines at Sebastopol opposite Vickers and the 27th. He forges a written order from the British commander that allows him to lead the brigade’s impossible charge against the well-fortified Russian positions. Vickers and the Amir die on the battlefield as Tennyson’s poem is emblazoned on the screen. The charge is portrayed as turning the tide of the Crimean War for Great Britain.

It was absolute applesauce. The Amir, Suristan, the 27th Lancers, and Chukoti were fictional entities. The charge occurred in 1854 against the Russians during the Battle of Balaclava. Sebastopol was under siege until the following year and had nothing whatsoever to do with the charge. The actual charge was an ignominious blunder that accomplished nothing other than the useless killing of several hundred British soldiers. The script’s contrivance of an evil Indian amir who initiated a treacherous massacre and ended up allied with Russians during the Crimean War was a fantasia that established the British Raj theme of the film, with which Wallis sought to replicate the success of The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935).

The anglophile in Hal Wallis fretted about the grotesque historical inaccuracies: “If we are to save ourselves from a lot of grief and criticism in England, we must make our picture [as] historically accurate as possible.” But it was too late to worry about truthfulness and the possibility of hurt feelings across the Atlantic Ocean. The cast was assembled, the sets were being built, and the script was written. Wallis settled for opening the film with a detailed disclaimer that declared that the story and historical events were fictionalized.

Eager to direct an epic with spectacular battle sequences, Curtiz begged Wallis for the assignment. The executive producer let him sweat it out a while. Wallis used director Frank Borzage as a stalking horse to extract a promise from Curtiz to stick to the script and follow orders. Curtiz pledged total obedience, then reneged as soon as the cameras rolled.

Jack Warner, Michael Curtiz, Hal Wallis in war council over scripts and contracts.

He shot himself in the foot with Jack Warner before the production began by reinforcing the perception that he wasn’t overly concerned about what was in the script. In a memo, Warner recounted to Wallis a luncheon conversation he had with Curtiz about the forthcoming epic:

“All he talked about were the sets and that he wants to build a fort somewhere else, and all a lot of hooey. I didn’t hear him say anything about the story. In other words, he’s still the same old Curtiz — as he always will be! Bischoff was there at the time, and I told him that we don’t want to go any place for the fort or any other locations other than the ones you have already picked out, so for Lord’s sake, get ahold of Mike and set him on his prat and let him make the story and not worry about the sets. Let the Art Director worry about this; he’s getting paid for it.”

— Jack Warner

It was as if Curtiz believed he was still at Phönix-Film in Budapest or lunching with Count Kolowrat. Warner was running the most efficient movie factory in the world. He wanted Curtiz to direct Light Brigade and wasn’t interested in any of his ideas about production design and sets, particularly if they would cost additional money.

Wallis, Curtiz, and the rest of the production team mapped out the script with specific scenes scheduled for Lone Pine, Lake Sherwood in Ventura County, Lasky Mesa, and Chatsworth, out in the San Fernando Valley. Before he headed up to Lone Pine, Curtiz added to the list of preapproved sequences. He wanted to reinstate a horse stampede and a guerrilla attack that Wallis had previously removed. Studio production manager Tenny Wright cautioned that these additions would cost more money, but Curtiz got his way and the guerrilla attack was reinstated. The horse stampede was “restored” by inserting stock footage of running horses obtained from Futter Studios in a film-swap deal.

After reading the script, Curtiz was dismayed by the dull wrap-up. He laid out his concerns to Wallis:

“I know in my heart, you must feel as I do, that after a terrific climax, it would be dangerous to allow the story to end in a conversation between two old characters. I beg you to consider seriously my suggestions, knowing that we must find a more effective ending.”

— Michael Curtiz

Curtiz and Irving Rapper wrote a thoughtful finale with a lap dissolve from the dead Errol Flynn on the battlefield to a debate in the House of Commons decrying the military disaster, which culminates in Benjamin Disraeli’s saving the day with a stirring speech, stating that “our bitter rancor, gentlemen, will not resurrect our dead.” The scene shifts to a parade scene of the 27th Brigade in which Lord Raglan presents a posthumous Victoria Cross to Flynn for the final fade-out.

Wallis responded courteously but declined to use Curtiz’s proposed ending. Ego may have played a part, but in the end, it was about money. The executive producer was not about to build another set or hire more actors for a newly conceived ending with production already under way. Wallis even attempted to obtain footage from The Lives of a Bengal Lancer to save money on Light Brigade, but Paramount turned him down.

Although the Light Brigade would be a beautifully shot picture, it certainly didn’t appear that way to Wallis shortly after the start of production. He was determined to curtail Curtiz’s peccadilloes before the picture progressed too far to stop him. Curtiz immediately indulged his habit of changing approved wardrobe after adding a clutch of white feathers to Surat Khan’s (C. Henry Gordon’s) turban. Wallis had the scene filmed over again and threatened to remove Curtiz from the film: “I’m not going to suffer through this picture with him like I did on Captain Blood and I am not going to fight him all the way through.”

Fort set in Lasky Mesa, Calabasas California.

After discussing in detail with Curtiz what was needed before the director went to Lasky Mesa to film the Chukoti fort sequences, Wallis previewed the initial dailies from the location with disgust. Beyond fulminating over Curtiz filming Flynn through a rotating waterwheel, Wallis was distraught over footage shot inside the fort that was muddled with people who were not principal actors. There were women with pots on their heads and children running around, along with assorted goats and horses. Curtiz envisioned the fort as it was in the script: a small frontier outpost crowded with soldiers and sepoys along with their families, who were to be slaughtered by the Amir’s barbarous host. Wallis wanted long lines of British troops in formation, clean shots of a tidy headquarters, and, above all else, close-ups of the actors whenever they uttered a word of dialogue.

Once again, it was the cinematic cultural divide between the executive producer who grew up in Chicago watching plays and nickelodeons and the director from Budapest with an artistic sensibility—and a reverence for realism—bred into his bones from the time he directed his first film (when Wallis was twelve years old). Despite their growing friendship, Wallis was fed up. In a detailed three-page memorandum, he laid out instance-by-instance where he thought Curtiz was going wrong with the filming, sending copies to producer Sam Bischoff and Tenny Wright. Wallis concluded in purposeful language:

“I have to go through this with you on every picture and I am beginning to wonder why. . . This is the last note that I am going to write you on this picture. . . . From now on, I will expect you to shoot the script and the story, and I want you to stop shooting through foreground pieces. I want the camera in the clear, and I want you to forget about all of this crap about composition because if the story is no good you can take the composition and stick it!”

— Hal Wallis

Four days later, Wallis upbraided Curtiz for not shooting close-ups from different angles, that is, cutting in the camera. He wrote another note to the director and the tone was ominous: “I remember about four months ago when you came to my office and pleaded to be allowed to make this picture and promised me that if you got it you would absolutely behave and do everything you were told to do and I would not have any trouble with you on the picture, but I have had one headache after another.”

It had finally become personal for Wallis, and Curtiz realized he was licked. The director had to compromise or he would be removed from the film. Quitting was not an option. If he walked off the picture, his career would be jeopardized. He had seen firsthand what happened to people who crossed Jack and Harry Warner, and his application for citizenship was still pending. Curtiz began letting the close-ups and two shots run full, and he reduced the number of foreground compositions in favor of the style Wallis preferred.

Michael Curitz (seated), Olivia de Havilland, Errol Flynn on the set.

Both Flynn and de Havilland were unhappy about laboring under a director they considered a tyrant as well as with a script that seemed to be a juvenile adventure story. Flynn looked smashing in his British uniform along with his new mustache (championed by Jack Warner), which the actor would maintain for nearly his entire career. There were no more of the sweaty palms and clenched teeth of Captain Blood. His comfort in front of the camera allowed him more time to reflect on the vagaries of movie stardom. No one was more let down than Flynn when it was announced that Curtiz, and not Borzage, would direct The Charge of the Light Brigade. Working outdoors in the freezing mountains of Lone Pine with spartan accommodations and bad food, Flynn found his distaste for the director evolving into a loathing that raised his frigid body temperature. Even though the company was in Lone Pine for only a week, Flynn felt like a member of the Donner party trapped in the Sierra Nevada during the winter of 1846:

“The wind was like a knife; it cut through everything, and it raced through our thin costumes. . . . Meantime the hard-boiled Curtiz was bundled in about three topcoats, giving orders. . . . I didn’t know enough to tell him to give me one of his coats, or to drop dead. He didn’t care who hated him or for what. He’d keep us waiting hour after hour sitting on the horses, freezing to death.”

— Errol Flynn

Being immersed for long periods in the fetid water of Lake Sherwood or buffeted by the heat and dust of the San Fernando Valley didn’t improve Olivia de Havilland’s disposition, and neither did her role in the film. Inserted into its historical contortions is a trite love triangle between Vickers, Elsa (de Havilland), and Flynn’s brother, Perry, a fellow soldier played by Patric Knowles. Elsa is betrothed to Geoffrey Vickers, who returns to India to find her in love with his younger brother. It was the same dusted-off plot from dozens of other potboilers. She ended up disliking Curtiz nearly as much as Flynn: “Curtiz was a Hungarian Otto Preminger, and that’s that. He was a tyrant, he was abusive, he was cruel.” After viewing the completed film, de Havilland thought her performance was awful.

David Niven, who was borrowed from Sam Goldwyn and cast as Flynn’s heroic aide, claimed that Curtiz’s language malapropisms were a “source of joy to all of us.” The future author recalled Curtiz’s staging of horses during one scene. “Okay,’ he yelled into a megaphone, ‘Bring on the empty horses!’ Flynn and I doubled up with laughter. ‘You lousy bums,’ Curtiz shouted. ‘You and your stinking language . . . you think I know fuck nothing. . . . Well let me tell you—I know FUCK ALL!’”

In his memoir Niven also wrote about Curtiz’s personal involvement in a cruel practice that allegedly resulted in the mass crippling and destruction of horses: “Curtiz ordered the use of the “Running W,” a tripping wire attached to a foreleg. This the stunt riders would pull when they arrived at full gallop at the spot he had indicated, and a ghastly fall would ensue. . . . Flynn led a campaign to have this cruelty stopped, but the studio circumvented his efforts and completed the carnage by sending a second unit down to Mexico, where the laws against mistreating animals were minimal, to say the least.”

Niven’s account was partially accurate. Flynn apparently did report the maltreatment of horses to the Humane Society at some point. He despised any type of cruelty toward animals and blamed Curtiz for the abuse. Flynn’s widow, Patrice Wymore, told me, “I know Errol was terribly incensed at his [Curtiz’s] treatment of animals.” But contrary to Niven’s assertion and other published reports, no portion of The Charge of the Light Brigade was filmed in Mexico. His claim concerning Curtiz’s responsibility regarding the mass inhumane treatment of horses appears to have been grossly exaggerated.

Errol Flynn breaching the ramparts.

Nearly every man in Hollywood who could skillfully ride a horse—including the author’s great uncle—appeared in the film. Curtiz himself did not necessarily order the Running W to be used. Use of a trip wire held by the rider and attached to a foreleg was standard practice in the industry at that time. Yakima Canutt, the legendary second-unit director and godfather of movie stuntmen, lost just two animals to freak accidents in more than half a century of continually handling horses in action movies. In his memoir Canutt provided clarity concerning the use of the Running W: “It was something that caused a lot of controversy for stuntmen and Western producers. I remember reading an article written by an officer of the Humane Society that stated we were tying wires on the horses’ legs and crippling them so badly that they had to be killed after the stunt. The Running W, used right, will not cripple a horse. I have done some three hundred Running Ws and never crippled a horse.”

After Canutt demonstrated the proper use of the Running W for a group of Los Angeles Humane Society officials at Vasquez Rocks, they approved the practice for use in Virginia City, a 1940 Curtiz film starring Errol Flynn. Canutt remembered: “It was generally understood in Hollywood that Flynn had reported to the Humane Society about horses being mistreated, but it wasn’t on Virginia City. I did a couple of Running W’s for him in that picture, and he always watched me doing it and all he ever said was, ‘Now why don’t all the fellows do them that way?’”

Unfortunately, Canutt wasn’t assigned to Light Brigade. The second-unit director hired to direct most of the key action sequences was B. Reeves “Breezy” Eason. According to the director Andrew Marton, Eason was “a crazy, drunk Irish-American, happy-go-lucky, who had the uneducated man’s flair for doing the right thing at the right time.” He was generally regarded as the best second-unit action director in Hollywood. Eason reportedly earned his nickname by always printing the initial take of an action shot (Eason apparently assumed the nickname from his late son, a 1920s child actor who was accidentally killed on location by a tragic accident), but the moniker could also be ascribed to his attitude toward safety. Eason took extreme risks in directing action sequences and was indifferent about the treatment of animals so long as he captured the necessary footage. Although his work was usually confined to Westerns, Eason made his reputation by directing the chariot race in the 1925 version of Ben-Hur, a production marred by perhaps the worst episode of prolonged animal abuse in motion picture history. During the production in Rome, an estimated 100 to 150 horses died during Breezy Eason’s direction of the chariot race action scenes. Rather than deal with the inconvenience and cost of treating injured horses in Italy, they were simply shot dead and sold by the wranglers for horsemeat. Some of the dead animals were used in posed publicity shots and lobby cards by Metro. The production of Ben-Hur became a chaotic mess; none of the Rome chariot footage was usable. When Eason staged the sequence over again in Culver City, a disastrous collision killed four horses. Yakima Canutt diplomatically remarked about Eason, “I sincerely admired him for his ability as an action director, but I always felt that he took too many risks.”

The bulk of the action sequences were filmed at Lasky Mesa during the first week of June; Curtiz and Eason directed the charge scenes using separate units. The scenes required 280 extras and 340 horses and were filmed with multiple cameras along a thousand-foot bulldozed road that paralleled the horse riders. The scenes included explosions from rigged detonations on an open plain, as men on horseback at full gallop took falls. At least two stuntmen were hospitalized with severe leg injuries. The final stunt and action sequences of the charge were filmed in Sonora, California, near the foot of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The studio had already been lucky after a spooked elephant ran amok during an earlier leopard-hunt action sequence in the film that Eason had shot at Lake Sherwood. The agitated pachyderm was caught before any injuries occurred. Warner Bros. would experience nothing but misfortune during the week of June 14 in Sonora.

The Sonora location was logistically favorable—a wide plain in a valley surrounded by hills on three sides—but the ground was a thin layer of soil over solid rock. Eason approved the site and had a six-hundred-foot-long trench excavated along one edge of the plain to install a car with multiple cameras that could film the riders at a low angle, along with other trenches for camera placement. The use of dynamite created dagger-like protrusions in ditches that resembled craters. After a day for setups, Eason began filming stunts and horse falls with more than sixty riders, upward of eighty-one horses (approximately thirty of these were locally purchased), sixteen cameramen, numerous assistants, a fire engine, and an ambulance. By the last day of filming, two ambulances were needed.

Powder technicians rigged dozens of explosives that were triggered as the riders galloped through the mayhem toward the end of the valley. One technician was treated for sunstroke and a stuntman reportedly broke his neck. Other riders were injured when they were thrown or fell on the rocky terrain. The horses fared worse. After Eason concluded filming the stunts, including six Running Ws and six pitfalls, two injured horses had to be put down and another subsequently collapsed and died. The local chapter of the ASPCA discovered what was going on and dispatched a representative to investigate before the company could leave or cover up what had happened.

On June 29, 1936, three Warner employees, including Eason’s first assistant, Jack Sullivan, pled guilty in court to animal cruelty and were sentenced to pay a fine of fifteen dollars and received a suspended ten-day jail sentence for using the trip wires that caused the death of the horses. Frank Mattison, who fretted about the second unit expending overhead funds by sitting around in Sonora, viewed the situation as a nuisance. Mattison facilitated the court pleas without first conferring with the Warner legal department. The guilty pleas to animal cruelty by Warner Bros. employees were reported in San Francisco newspapers and picked up by the Associated Press. More than one thousand letters of protest poured into the studio. Animal welfare organizations in America and England began to line up against the film.

Jack Warner wasn’t about to let his expensive epic suffer from bad publicity that he considered manifestly unjust. He immediately orchestrated a legal counterattack. The studio’s attorney Roy Obringer accused the ASPCA investigator of exaggerating the events, which opened the floodgates for Humane Society articles relating the deaths of “three or four hundred horses.” The studio maintained that none of the destroyed horses had been injured because of the use of the Running W or trip wires. Obringer and A. J. Guthrie traveled to San Francisco and showed the local head of the Humane Society photos of the dead horses, which had no trip wires attached to their forelegs. The ASPCA was unconvinced and stood behind its investigator. Archival Warner legal files revealed that the ASPCA investigator who originally showed up in Sonora, a man named Girolo, hit up Frank Mattison for a hundred-dollar “loan” and later tried to extort additional money from Warner Bros. personnel. The studio theorized that Girolo notified the San Francisco newspapers about the guilty pleas when his second shakedown attempt was rebuffed.

The attending veterinarian, Warner Bros. employees, and other principals on the scene provided signed statements and sworn affidavits that attested to the nature of the injuries of the two horses that were put down, along with the third horse that subsequently died of heart failure. There was a fourth horse that was killed as a result of falling and striking a sharp rock during a scene filmed in Chatsworth. Unable to reverse the guilty pleas of its employees, Warner Bros. concentrated on correcting reports about the deaths of numerous horses. The studio successfully sued the Women’s Guild of Empire in Great Britain for libelous statements about the film that included a recommended boycott.

As a result of the legal and publicity ramifications caused by their alleged mistreatment of horses, Warner Bros. instituted an internal policy requiring a Humane Society representative to be present at every film production involving horse and animal stunts. The bad publicity was exacerbated by the subsequent drowning death of a horse after a stunt jump off of a 70-foot cliff into the Lake of the Ozarks during Twentieth Century Fox’s production of Jesse James (1939) which kept public awareness focused on the inhumane treatment of animals by the motion picture industry. The use of the Running W and pit falls in films was permanently banned in December 1940.

Although it is possible that more horses could have been killed in Light Brigade, there is not a scintilla of evidence that other animals died or that Warner Bros. orchestrated a cover-up. The mythical mass murder of horses ended up historically tarring a single individual: Michael Curtiz was identified as being responsible for the “carnage,” to use David Niven’s term. That the director wasn’t even present at the location where three of the four animals were injured and put down and was a skilled rider who loved horses didn’t matter. Although the treatment of horses on this film didn’t come close to the horrors of Ben-Hur during the previous decade, Curtiz’s reputation as a directorial martinet made it convincing for Flynn, Niven, and others to ascribe the blame solely to him. It also didn’t help that Breezy Eason removed his name from the credits in deference to Curtiz. Conversely, it is debatable whether Curtiz would have done anything differently even if he had been present in Sonora. The very nature of the production lent itself to severe injuries to horses and their riders. Light Brigade‘s reputation has suffered due to the evolution of public perception about the treatment of animals. Horses were still viewed from a frontier and agrarian perspective in 1936. Popular sentiment concerning the treatment of horses and other animals has changed radically since then. It is difficult for many modern viewers to watch the thrilling battle scenes in the picture without averting their eyes as horses and their riders tumble wildly.

Errol Flynn (in costume), Michael Curtiz, far right.

Curtiz was in his element. He loved working outdoors, staging the battle scenes, coaching the actors, and manipulating the cameras to best advantage. At Lake Sherwood he jumped up on a large boom and acted out the scene to several hundred extras by brandishing his microphone like a rifle. The columnist Sheilah Graham skirted Tenny Wright’s ban on visitors and observed Curtiz in action at Calabasas: “‘More smoke up here,’ shouts director Michael Curtiz. ‘British and Russian lancers, get on your horses!’ yells his assistant Jack Sullivan. In the general confusion an electrician at the switchboard pushes a button and a large explosion results. A horse throws its rider. ‘No matter what happens, no matter who gets hurt, no one is to run into the shot,’ warns Sullivan. ‘If anyone gets wounded, he gets extra pay,’ reminds Curtiz.”

The Charge of the Light Brigade charged to the top of the box-office charts, bringing in grosses that were nearly identical to Anthony Adverse’s. The bravura sweep of the film, the heart-stopping battle scenes, and Max Steiner’s thrilling score — his first of over 150 for Warner Bros. — overcame any concerns about cruelty to horses, a weak script, and the rewriting of military history.

May 5, 2019

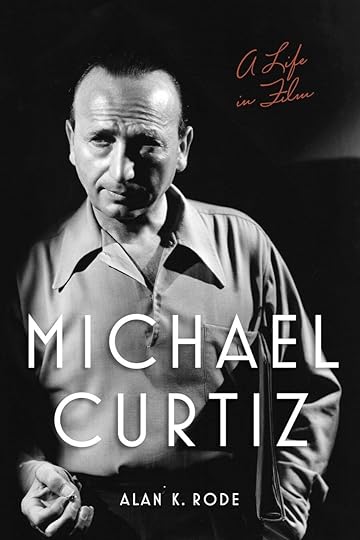

N.Y. Review of Books: David Thomson’s review of Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film

[lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”false”]

David Thomson[/lgc_column][lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”true”]DECEMBER 20, 2018 ISSUE[/lgc_column]Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film

by Alan K. Rode

University Press of Kentucky, 681 pp., $50.00

We’ll Always Have Casablanca: The Life, Legend, and Afterlife of Hollywood’s Most Beloved Movie

by Noah Isenberg

Norton, 334 pp., $27.95; $17.95 (paper)

Arthur Edeson (director of photography), Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman on the set of Casablanca, 1942

We used to think we knew what a film director was. First, it was someone who hardly existed; then, a mighty egotist; later a professional in charge of a factory product. Next, he or she was raised to the status of auteur, artist, or genius. And now…well, directors have to be all things. So it’s valuable to note the insouciant flexibility of Michael Curtiz, the Captain Renault (that’s Claude Rains in Casablanca) of movie directors.

Six writers were paid for script work on Casablanca, and in total they received $47,281. The producer, Hal Wallis, took away $52,000; Humphrey Bogart received $36,667; and for loaning Ingrid Bergman for the picture, her proprietor David O. Selznick got $25,000. No one on the Warner Brothers project received as much as its director, Michael Curtiz—he made $73,400. Although he was in charge of what may be the most treasured film ever made in Hollywood, there was still confusion at his studio whether his name was spelled “Curteese,” “Curtess,” or even “Curtis.” Some people never quite grasped Curtiz’s English, wrapped up as it was in his flamboyant Hungarian accent. He had also once borne the name Mihály Kertész, and before that Emmanuel Kaminer. At Warner Brothers in the flux of war and displaced persons, the names on contracts or letters of transit could get confused.

An orthodoxy was laid down in 1968 by Andrew Sarris, in his influential book The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929–1968, that Curtiz ranked in the “Lightly Likable” category of directors, among the blithe beneficiaries of the studio system. Still, he had one enduring masterpiece, Sarris thought, “the happiest of happy accidents, and the most decisive exception to the auteur theory.” This was Casablanca, the movie that Noah Isenberg says we’ll always have.

Lightly or not, Curtiz could get very emotional about his pictures; he was known for crying. He had objected to casting Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce, because he wanted Barbara Stanwyck. But then Crawford did a screen test—she had just been dropped by her studio, MGM, and she needed to make a comeback. The right desperate look was in her eyes. The tough Hungarian director wept, and she was on her way to a personality Oscar, like the one James Cagney had won for Yankee Doodle Dandy, another Curtiz picture.

Is there a unifying force in Casablanca, Yankee Doodle Dandy, and Mildred Pierce, probably the best-known Curtiz films? They are all in black and white. All three came from Warner Brothers and run between ninety minutes and two hours. Casablanca is a wartime love story about commitment; Yankee Doodle Dandy is an intoxicated biopic in which the legend of the Broadway producer and composer George M. Cohan turns into the dynamic myth of Jimmy Cagney himself; Mildred Pierce is a noir about the wretched ordeal of being a mother. In all three films we’re asked not to notice the style so much as ride on it. In Casablanca, when Rick reencounters Ilsa (because Sam has played the forbidden song, “As Time Goes By”), he charges across the café floor and stops short on seeing her. The fury in his face fights the lush melody. You could say that this effect depends on the writing and cutting, as well as on the vivid faces. All true, but when Curtiz filmed, he had the imperative of editing in his head already. He made us feel, in the way he shot each scene, that our attention was vital. He trusted this credo of the system—don’t be boring.

Artistic integrity meant less to Curtiz than continuing to work. He did the pictures assigned to him, without much complaint and with little thought of interfering with the scripts. At Warner Brothers, he might make four films a year. Before that, in Europe, he had done seven or eight. But Sarris assessed him in a single paragraph. As Alan K. Rode puts it in Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film, he “made so many pictures he ended up being taken for granted.”

The driving force in Curtiz’s films was a belief that the many skills in studio collaboration could handle just about any story that fell within the positivism of Hollywood in that era. It was a unity based in pure versatility, to the point of creative self-effacement. It’s hard now to find keynote personal touches in Curtiz’s films—perhaps they were all ironed out by the system. But in movies crammed with characters, like Casablanca or The Adventures of Robin Hood, there is no hint of confusion. Supporting actors are never neglected. Curtiz became a model director at Warner Brothers in part because he could shoot action sequences with assurance in an age when action often mattered more than character or plot.

During the war years he directed eighteen feature films, plus a twenty-minute Technicolor short called Sons of Liberty, in which Claude Rains played Haym Salomon, a Polish Jew who helped fund the American Revolutionary War. The public loved this gesture; it won the Oscar for best short subject. Rode says it’s very dated now, but it’s a reminder that Casablanca was made by a gang of refugees from Europe, many of them Jewish and with relatives lost in the Holocaust. The survivors kept cool about their stories of good luck and bad, and in Casablanca Victor Laszlo’s concentration camp experience is rendered as an elegant scar on Paul Henreid’s brow.

There’s a more general point to this story. Rode’s magnificent biography comes too late for him to have interviewed many of those who worked with Curtiz, but still he has spared nothing in tracking people down as far afield as Budapest. Curtiz was born there in 1886 to Jewish parents, a carpenter and an opera singer. As a boy he constructed a toy theater in his home where he could arrange cardboard figures in plays, with lighting and sound effects. He wanted to be an actor and studied at the Budapest Royal Academy of Theater and Art before serving a year in World War I, during which he was wounded on the Russian front. He and Claude Rains were the only leading figures associated with Casablanca who had seen combat. (Bogart was in the navy, but it’s unlikely he saw action.)

Though Kertész—as he started calling himself in 1905—is regarded as a founder of Hungarian cinema, few of his early films survive. But it’s clear that he became an admired figure, a sardonic actor, and a ladies’ man as handsome as a matinee idol. He married one actress, Lucy Doraine, and had a lengthy affair with another, Lili Damita, before he married Bess Meredyth, a screenwriter who served as a useful adviser but took to her bed in despair because of his passing affairs and forgotten illegitimate offspring.

Rode doesn’t present Curtiz as an especially pleasant or considerate man. He behaved as if movies were more important than anything else. Inclined to lose his temper, Curtiz relentlessly stayed on schedule and budget. He was also a natural melodramatist, capable of making stereotypes feel fresh and delightful. In Budapest, he was a contemporary of Alexander Korda; they were both entertaining survivors and hard-nosed opportunists.

After the war, Curtiz moved to Vienna and made several films in German. Vienna was a center of influence on filmmaking. The Austro-Hungarian atmosphere of amused cynicism and bittersweet romance marked Curtiz’s work there. He was seldom sentimental or forgiving in his pictures. In the photograph on the cover of Rode’s book he looks like a worldly figure from The Third Man, with a shady past and a mocking remark on the tip of his tongue. His urbanity and wit would serve him well in Hollywood. No matter how much Curtiz mangled the English language, he maintained an authority over his feisty, opinionated stars—Cagney, Bogart, Edward G. Robinson, Errol Flynn, and John Garfield, not to mention Bette Davis, probably the toughest of the bunch.

He arrived in America in 1926 and soon went to work for Warner Brothers. There he befriended the production chief Hal Wallis: they played polo together and shared a ruthless, businesslike attitude toward stories and stars. Just as he had promised the studio, Curtiz turned his hand to anything: he did horror pictures (Doctor X, Mystery of the Wax Museum); he handled the only screen pairing of Bette Davis and Spencer Tracy in 20,000 Years in Sing Sing; and he directed Al Jolson in Mammy. Decades later he got on very well with Elvis Presley on King Creole. He launched a handsome Australian novice, Errol Flynn, in Captain Blood, The Charge of the Light Brigade, and the ecstatically boyish The Adventures of Robin Hood. Curtiz said he was an ideal director for these studies in valiant leadership, with the star’s bold grin and virtuoso swordplay, since he had fenced for Hungary in the 1912 Olympics. This was an invention, but maybe he believed it himself.

Robin Hood feels under serene control. The truth was more complicated. It was Cagney who was first cast as Robin, but then he got into a contract dispute with the studio, and Flynn was called in. The film, shot in Technicolor, promised to be the most expensive picture Warner Brothers had yet made, and Curtiz was dismayed when the direction job was given to William Keighley, a journeyman. But Keighley failed at the big action scenes. So Curtiz was assigned, and his reputation was enhanced for rescuing a big project. His Robin Hood is still the classic version of that legend. He understood that Flynn moved with a grace and élan that matched the surging musical score by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. The set-piece sword duel between Flynn and Basil Rathbone is closer to a Fred Astaire routine than a reliable depiction of how men fought in the twelfth century.

Before he made Yankee Doodle Dandy and Casablanca, Curtiz was already established as the top director at the studio, famous for his versatility. He was also regarded warily because of his taste for beautiful shots and scenes. The professionals at Warner Brothers thought he was unduly European, steeped in German expressionism and inclined to ignore plot for sheer style. Orson Welles once remarked that Curtiz had “no idea about dialogue, but a very, very good visual sense…. You can’t imagine how Hungarian he was.” Jack Warner scolded Curtiz on Four Daughters: “If you will stop all that superfluous roaming camera, Mike, you will make a great picture, as you always have.”

Did Warner miss Curtiz’s cunning? A reputation for stylish shots should not obscure his acute judgment of plot. Curtiz knew how to light and shoot Joan Crawford when she first appeared in Mildred Pierce, on the waterfront at night, close to suicide, with a line of shadow falling on her brow. That was new for Crawford. Maybe it was the cinematographer, Ernie Haller, who came up with it (Haller’s 185 credits also include Captain Blood and Gone with the Wind). But it could also have been Curtiz’s eye. If you study his films, they waste no time, they are invariably good-looking, but they are also greedy for action, whether in a duel or a glance. One will not find a scene in any of his films in which the dialogue or the acting seems like the clunky work of a man whose English could be comical. Possibly Curtiz contrived his accent as adroitly as he composed close-ups.

A feature of Noah Isenberg’s engaging study of Casablanca is his acknowledgment of the cast and crew’s expertise. So much care was put into the film’s lighting, set design, montage, and secondary performances that the audience in its innocence may have mistaken this Burbank North Africa for the real thing. (In fact Casablanca was liberated by Allied troops just as the picture opened.) But it was sheer make-believe passing as tough realism; wartime compromises and anguish were masked behind a noir flourish. Curtiz lost close relatives in Auschwitz, people who never got their letters of transit. But he knew not to go too deep in that direction.

Isenberg’s book is not as rich as his earlier study of Edgar Ulmer, but it is an ideal introduction for new generations and for those who don’t know Aljean Harmetz’s more complete Round Up the Usual Suspects (1992). Both Harmetz and Isenberg dispel the myth that Casablanca was just a happy accident and that no one understood where the story was going or knew who should star in it. Producer Hal Wallis had always wanted Bogart as Rick. Ilsa was the only part in doubt—she might have been played by Hedy Lamarr or Michelle Morgan. But time proved that Bergman was the right, immaculate choice.

Stories still circulate that Bergman didn’t know during shooting whether she was going to stay with Victor or go with Rick. This was studio romance, and a way of comparing the insouciance of the film’s characters with the nerve and fatalism of studio filmmaking. It would actually have been impossible under the Production Code for Ilsa to drop her husband. The studio knew where it wanted to go, and a group of craftsmen understood how to get there. Maybe Curtiz didn’t care much about the story. He put the momentum of the project above all else and never risked uncertainty. There are no mistakes in Casablanca. It’s a clue to the longevity of the film that, despite the hideous dilemmas and horror of war, this version of Casablanca feels like an exciting place to be.

By 1968, filmgoers were ready to believe in the politique des auteurs, the theory that directors were the unique creators of their films. The idea naturally had a French label, for young French writers (François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Éric Rohmer) had first articulated the case for the genius of such directors as Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray, and Douglas Sirk. No one did more to develop that theory in the US than Sarris, who in The American Cinema made an ambitious attempt to rescue Hollywood films from professional anonymity.

The Warner Brothers where Curtiz flourished for so long, however, did not believe that directors were heroes or artists. Curtiz was the studio’s top director, but Warner Brothers had a team of professionals who took on the offered assignments. They included Raoul Walsh (a great hero to the French, and the director of The Roaring Twenties and White Heat), Mervyn LeRoy (Little Caesar, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang), Vincent Sherman (The Hard Way, a remarkable story of sibling rivalry, starring Ida Lupino), Archie Mayo (The Petrified Forest, Black Legion), Irving Rapper (Now, Voyager), Alfred E. Green (Dangerous, which won Bette Davis her first Oscar), and William Dieterle (The Life of Emile Zola). There were only two directors at the studio with an unquestioned personal style: Busby Berkeley and Howard Hawks. Berkeley did erotically unrestrained musicals with troops of beautiful women. Hawks was there just a few years, but long enough to make two masterpieces: To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep, ostensibly noir adventures but imbued with Hawks’s mastery of screwball comedy and his sultry idealizing of flirtation.

Sarris had justifiable heroes, directors insistent on their own style. Hawks, John Ford, and Hitchcock were industry survivors, but a number of directors were never comfortable with the impersonal smoothness that the studios demanded (what Julius Epstein, a writer on Casablanca, called “slick shit”). Many of those mavericks were eventually cut loose from the herd: Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, Max Ophüls, Josef von Sternberg, Erich von Stroheim, Jean Renoir, even D.W. Griffith.

Nothing detracts from the wayward achievements of those men, but nothing should stop us from appreciating directors like Michael Curtiz either. Today, mainstream American cinema has too few directors whose manner is recognizable as soon as a film starts. But there are Curtizian careers if we care to notice them. Many viewers have taken immense pleasure from searching long-form television series like The Sopranos and Breaking Bad. The first was created by David Chase and the second by Vince Gilligan; it was they who organized the series and the men and women who contributed to them. But the directors who worked on these shows, like Tim Van Patten or Michelle MacLaren, remain relatively unknown.

MacLaren did eleven episodes of Breaking Bad (more than anyone else). She also has directed four episodes of Game of Thrones, two of Better Call Saul, one of Westworld, and two of The Deuce. That’s about thirty-eight hours of film since 2009—the equivalent of nineteen movies. No feature film director today comes close to that work rate. Van Patten has done twenty episodes of The Sopranos, eighteen of Boardwalk Empire, and three of The Wire. I’m not sure these directors wish to be picked out, for they belong to an ethos of team spirit. They know that in modern television the contributions of stars, screenwriters, and showrunners dominate our experience.

The auteur theory was right for its time, but it’s fading away. The studio system of the 1930s and 1940s valued directors for their efficiency and for the way they understood what was expected of them. In the 1960s and 1970s, it seemed necessary for Sarris and others (myself included) to praise thematic ambition at the expense of mere competence. But that earlier uniformity had been responsible for what we now call the golden age of American cinema. It’s a tribute to Alan Rode’s book, through all its unstinting research and admiration for its subject’s life, that it endorses Curtiz’s willingness to do anything he was asked to and do it in high gloss.

He directed 181 films in fifty years of work. Aside from the films already mentioned, he also made Night and Day (a deranged biopic in which Cary Grant plays a sanitized Cole Porter), Life with Father (a treasured family hit, starring William Powell), Jim Thorpe—All-American (with Burt Lancaster as Thorpe), and White Christmas (Bing Crosby and Rosemary Clooney). That 1954 picture was a success at the box office and still plays during the holiday season. Many of the Jews who succeeded in Hollywood took delight in adapting to the Christmas spirit. It was part of their survivor instinct and an example of the way talented immigrants embraced the film industry’s mixture of optimism and cynicism. Curtiz gave us, among many other memorable characters, Captain Renault, maybe the most beloved figure in Casablanca, and a tribute to cynical panache. Like Renault, Curtiz usually landed on his feet and scooped up the winnings. Was he an auteur? No, far better than that.

© 1963-2018 NYREV, Inc. All rights reserved.

June 11, 2018

Latest Book – Now in Paperback

May 7, 2018

Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival 2018

The 19th annual Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival opens Thursday 10 May 2018 at 7:30 pm at the Camelot Theaters in Palm Springs, CA. with FAREWELL, MY LOVELY (1975) plus scheduled guest appearance by Jack O’Halloran.

The 19th annual Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival opens Thursday 10 May 2018 at 7:30 pm at the Camelot Theaters in Palm Springs, CA. with FAREWELL, MY LOVELY (1975) plus scheduled guest appearance by Jack O’Halloran.

Other guests include Ruta Lee (WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION ), Victoria Price (THE WEB) and Victoria Mature (KISS OF DEATH).

Don’t miss these dark classics on the Camelot Theater’s big screen with festival producer Alan K. Rode, TCM’s Eddie Muller and film historianFoster Hirsch introducing the films.

The screening schedule and ticket information are available here: https://arthurlyonsfilmnoir.ning.com

March 30, 2018

Hollywood’s Great Deluge

TCM will be broadcasting NOAH’S ARK on April 4, 2018 that will commence a month long spotlight on the films of director Michael Curtiz. Here is some background on the making of the film adapted from MICHAEL CURTIZ A LIFE in FILM