Rusty Barnes's Blog: Fried Chicken and Coffee, page 32

March 11, 2012

Dog Days, fiction by Kevin Winchester

Even before the cash changes hands Ard is thinking of how quickly the eight ball will be gone. The count looks light but it always does any more. He unwraps the twist tie, touches his little finger to the rock, then to his gum and his brain measures: one thousand one, one thousand two, one thousand three, one thousand four. He clicks his front teeth with each number and on four the only feeling that reverberates into his gum is the sound wave to his inner ear. Good. Ard drops four hundreds on the table and picks up both bags.

Outside the August sun is white and stifling. The glare from the pearl hood of the Caddy shocks him and Ard slips on his shades before he eases out into the street. He wishes it were February and raining.

Three blocks down he turns right on Ashland, goes a half a block and pulls into the lot, checks his watch. 3:55. He waits. Checks the dial again. 3:58. Across the lot and up the marble steps, through the heavy oak doors. He moves to the last door on the right, checks his watch again to assure himself its four, goes inside.

"Bless me Father for I have sinned. It's been a week since my last confession."

"I fail to see the humor. And it's getting a bit old."

"Ah, my big brother's in a mood. Confessional stress? I might have a little something for that."

"Shut up Ard. I don't know about this anymore."

Ard pauses. "About what, Jamie?"

"This. I am a priest, you know, we're not teenagers. I have responsibilities, vows. I've got an obligation; to you, even."

"Don't start. Not everybody wants to be saved, Padre. Besides, there's some in your religion that have worse habits." Ard pulls one of the bags from his shirt pocket.

"Maybe I shouldn't have taken the assignment here. I thought moving back would be good for us, for you. You and Rosa were the only family I had."

"I don't need you deciding what's good for me, Jamie. Now do you want the blow or not?"

"That night after Rosa Lee's funeral, I drove you to the bar because I was worried about you; what you might do. All you wanted was to cop a gram, and then I let you talk me into doing it again."

"And I got the flake right now. Come on, big brother; hear it calling you? Besides, you're the one got me started way back when. I was just returning the favor. So, you want it or not? It ain't like I can't put it to good use if you don't."

The pause lasts too long, gives Ard time to think. These secrets thread between the two brothers like an old tapestry, worn but somehow still intact. Growing up with the town drunk colors the perspective on things; weaves a patchwork version of history and events into both of them so deep they don't notice anymore. If Jamie cleans up Ard is afraid the last of those strands will unravel.

"When we were kids, teenagers, nothing made any sense to me. The Church gave me answers, made things clear. Lately, I'm not so sure."

"Well, you know what they say—God's just an imaginary friend for grown-ups." Ard leans to the edge of the bench. "So make a choice, you in or out? Daylight's wasting."

The pause is shorter this time and Ard grins when the curtain shuffles and two hundred and fifty dollars appear beneath the cloth. Ard counts it, then gently slides one of the bags back under the curtain before folding the bills into his shirt pocket.

"Glad to see the parishioners have been generous again this week. Always a pleasure, Padre. See you next week, same time, same weight."

Back at the apartment Ard is impatient. He unlocks his door and goes straight to his desk, gets the mirror and the blade, shaves a corner from the rock, chops it, cuts out two lines, rolls a hundred and they're gone. He waits for the drain to hit the back of his throat and when it does he smiles and cuts out two more lines that disappear neater than the first. He chops about a gram from the rock and carefully dumps it into the vial that he puts in his right pants pocket before tucking the rest of the bag in his left. Ard taps the razor on the mirror and lines up the residue. For an instant he thinks about Jamie and then frowns at his reflection before inhaling the last line. Ard sits back, rubs both eyes with the heels of his hands and then stares at the framed photograph on his desk. "Everybody has a story," he says to the image. His words sound hollow even to him and he thinks of heat and humidity and Hell before he rises to leave. He wishes it were February and raining.

Ard curses the heat and flips the Caddy's AC on high but he knows it needs freon. He drives through town, keeps an eye on his speed, then opens it up a bit after he crosses the railroad tracks, has it humming by the time he passes Charlie and Linda Wrenn's place. Ard pulls over just before he gets to JoJo's and scoops two more hits from the vial. JoJo and him were neighbors, before. He was an all right guy but he never bought blow. Never seemed to mind doing somebody else's though. When he pulls in the yard he sees JoJo at the edge of the woods behind the farmhouse, swinging a pick ax at the dirt.

"What you doing, Jo?"

"Gotta bury George Bush. Fucking ground's hard as a brickbat. Christ, we need some rain."

"GB's dead?" Ard sniffs and thumbs at his nose, hopes JoJo won't catch it.

"Pretty sure. He ain't moved in a day or so. Looks pretty stiff. Hand me that shovel." JoJo tosses a small pile of dirt out of the hole and grabs the pick ax again.

"It's too hot for this shit, let's go get a beer." Ard feels the sweat pooling in the small of his back, looks toward the pen. "GB'll wait."

"Go 'head on, I got to finish here. You think it's deep enough?" JoJo swings at the dirt again and the pick ax bounces back at him and nearly hits his bald scalp.

Ard looks at the hole while he struggles to keep his mind from racing back—back to her casket being lowered, disappearing below the surface, back even to the moment the fire started; but it's no use, he's there again and he can smell a brief hint of patchouli and jasmine that sends his fingers to the vial in his pocket, doesn't realize how hard he is pressing it into the soft flesh of his thigh but thinking of the white powder all the same, hears it calling him, whispering, until a pain shoots up through his femur, along his spine and then spikes into his right eye. The pain is familiar and it brings him back. "No."

"Shit." JoJo swings again, this time sinking the blade into the clay and wedging a chunk out of the earth and into the thick air. He steadies himself for another swing. "You could help me, you know. Little hard work do you good." JoJo grunts just as the blade strikes the yellow earth.

"Naw. Looks like you got it."

JoJo grunts again without looking up. He starts another swing then stops to wave the back of his hand at Ard. "I'll catch you at Red's after while. Damn dog would wait until the ground was baked concrete 'fore he decides to die. Asshole."

Ard starts toward the Caddy, wonders whether JoJo was talking about him or George Bush. When he reaches the car he decides he doesn't care. The dog was a big German Shepherd, dumb as cornflakes and always wanting to fight. He got into Rosa Lee's flowerbeds once after she'd spent two days putting in new bedding plants and shrubs. Ard didn't care for flowers so much but he'd sat on the back porch rubbing Rosa's shoulders after the work was done, looking at her looking at the plants, and the light in her eyes sifted over him like silky beach sand and he knew it felt too good, knew even then the feeling would somehow slip from his grasp. The next day, when he came home and found GB digging in the beds and all the flowers destroyed, he went straight for his shotgun. He raised the gun to his shoulder and yelled, he wanted the dog to see what was coming, but GB turned and growled before he charged him. Ard was so surprised he couldn't get off a shot and had to use the butt of the gun to knock the dog away twice before it finally ran for home. Ard's glad the damn brute is dead.

He does two more hits before he starts the Caddy, closes his eyes and waits for the rush. He sees the gash of earth JoJo was standing over, how the packed red soil yields to hard yellow bull tallow a few inches down and feels himself falling into the hole, feels the weight of the soulless dirt pressing on his chest until he opens his eyes and backs out of the drive. The low moan of the big V8 washes over him, cleans the last of the vision from his head. As he pulls off he sees JoJo bent and dragging George Bush toward the hole, the dog's legs sticking straight up toward the heavens, the two of them a struggling silhouette against the fading sun.

***

The gravel parking lot at Red's is already three quarters full. The building itself is made of cinderblocks, low slung and nondescript, but recently Red hired somebody to paint a beach mural on one wall. Years ago, when Ard and JoJo first started coming, the place was no more than a beer joint that doubled as clubhouse for Red's driving range. After the by-pass was finished and the new money discovered that land and taxes were cheaper out in the county and all the subdivisions sprang up, the place got trendy. Ard guessed the newbies figured it was safer driving a mile or two home from Red's than navigating the Lexus through Charlotte traffic after several rounds of apple martinis. Red had no idea how to mix a martini but the PBR's were ice cold and only a buck.

After two more quick bumps, Ard stashes the baggie in the glove box, the vial in his pocket and makes his way through the lot and across the new sand-filled patio area, winds around the wrought iron tables with umbrellas and sidesteps the moderately rich. Two guys in khakis and golf shirts stop Ard just as he makes the door.

"Nice ride." First Guy tips his beer toward Ard. "Ford, right? About a 59, 60?"

Second Guy nods. "You restore it yourself?"

Ard stands with his hand on the screen door, looks at his Caddy, then back at the guys. He can feel his heart clicking and realizes he's grinding his back teeth, the muscles along his jaw knotted tight. Needs a cold beer to wash the taste of benzene from his throat. Thinks he ought to smash his fist into First Guy's bleached teeth for fun but says: "59 Caddy. Won it off two faggots in a crap game out back. Fucking aftermarket AC don't work. When you guys see 'em tell 'em they owe me some freon," and he walks into the cool stale air of the bar.

He knows he should eat but every nerve is up on edge now and his mind is moving one notch quicker than everything around him, out of sync but manageable. Preferable. No need to dull it with food. Red slides him a Miller, Ard takes one swallow and goes to the john, locks the door. He's shocked when he sees the vial, empty to the point that he can't scoop another hit from the bottom and he's forced to dump what's left on the back of the stained urinal. The line's too thin and gone in an instant. The smell from the toilet makes him feel like he'll throw up. He chokes back the rising bile and goes to finish his beer.

"Rosa Lee's daddy and momma was in here the other night." Red pulls the stool across the bar from Ard, settles in. Most of the crowd is outside and the waitresses are handling them.

"They say anything?" Ard rolls the Miller back and forth in his hands.

"Small talk. Had a couple of beers, watched some of the game. I ain't seen them in here for a while. Wondered if they mighta been waitin' on you, you know, maybe you all was okay." Red winks at him with his good eye.

"I'm fucking fine. Can't say about Ross and Eileen. Anything come up about the fire report?"

"Naw. I figured that'd be done by now. You ain't heard nothing?"

"It ain't back yet. 'Sposed to be end of this week, I think. Thursday, maybe Friday." Ard drains the last of his beer and tosses a twenty on the bar. "Listen, hold my spot, I left something in the car."

Outside the two guys are standing beside the Caddy, nursing imported beers. Ard shakes his head and remembers when the only choices Red offered were Pabst, Bud and Miller. I ought to sell the car, he thinks, draws too much attention. He needs the guys to disappear, needs the Caddy's privacy to cut out the rest of his blow, but he knows the type. He'll have to humor them at least for a while or they'll never leave.

"How long is this thing?" First Guy asks.

"Twenty-six feet, nose to tail." Ard grins.

"And you really won it in a crap game?" Second Guy chimes in while First Guy walks the length of the car.

"Naw, I was just messin' with you. Ain't no gambling gone on here since Red closed the driving range. Used to keep a monkey in a cage out back, though. Monkey loved to smoke weed. We used to bet how many tokes before he went for his first banana. Damnedest thing you ever seen." Ard bristles as he watches First Guy run his hand along the tail fin of the Caddy.

"So where'd you get it?" First Guy asks as he kneels to inspect the bumper.

"Old man Jenkins, used to live over by Alton. You wouldn't know him; he was dead before all y'all started moving out here. Sat out behind his barn. I went over there squirrel hunting one day and saw it, bunch of weeds and briars grown up around it, going to rust. Said it was his boy's, but I knew his boy had got his insides blown out somewhere up the Mekong Delta. Said the boy parked it right there where I found it, back in June of '67. Asked his daddy to keep it for him till he come back."

Both men move to the front of the car, listening to Ard but never taking their eyes off the Caddy. Ard gauges the two men, wonders how long before they tire, how long before they spot the next best thing and leave him alone. He knows it won't be long until the dull ache settles across his sinuses and everything slows to a crawl. But right now he still has a nice edge.

"So I told Jenkins, I said, hell, its 1999, I don't much believe your boy's coming back."

"You didn't. What'd he say?" First and Second Guy are working in tandem now, one asking right on the heels of the other and Ard's not sure which one spoke first.

"Told me he didn't expect he was, but that didn't mean he was gonna sell his boy's car. Told me he didn't much think he wanted me hunting squirrel on his property no more, either."

"So how'd you end up with it?" First Guy takes a long pull from his bottle and makes a bitter face.

Ard laughs. "Beer tastes that bad I believe I'd switch brands. Old man calls me in the spring of 2000, says come get the car if you want it." Ard holds out his left arm and points to a small scar on his forearm. "Damn black snake had laid claim to it, bastard bit me when I went to haul it out."

"Damn," Both Guys in unison.

"Anymore old junkers over there?" First Guy laughs, "I might be willing to take on a black snake."

Ard walks to the back of the car and wipes the edge of the tail fin down with his T-shirt, leans to inspect it, wipes it again. "Nope. They found Griff Jenkins two days after I picked up the Caddy. Pistol still in one hand, picture of his boy in the other. Brains on the bedroom wall and blood all the way to his shoes."

Laughter rolls from the patio and all three men turn and look toward the knot of people there. Studying menus, ordering. Throwing recent slices of their lives across the table for entertainment, and Ard knows that even before the sound of their words die out they're already thinking of the next amusing story they'll tell. He can feel it, as if some unseen strand reaches from the crowd at the tables, stretches past him and anchors itself to the two guys in front of him, already drawing them back, pulling them through the uneasy silence that now surrounds them, surrounds Ard.

Ard cuts his gaze short and looks instead at the two guys. He knows them, hell, couple of choices here or there, he could almost be them. College boys, probably from New York, Jersey, maybe Pennsylvania or Ohio. Came down here to Duke or Carolina on their parents' money, graduated, moved back North for awhile then followed the money trail and sunshine back to good old Carolina. Good money jobs either at one of the banks downtown or one of the new hi-tech companies springing up everywhere, maybe real estate. Not a hard day in their life.

But it always came back to the choices. His grades had been decent in school, at least until they moved him and Jamie into the Thompson Home. It wasn't long after that he decided a sack of weed was a lot more interesting than a history book. And that Saturday night, the party. He should've left with Jamie, tried his luck sneaking past the nuns, but there was plenty of blow around and he didn't see any point in calling it an early night. The next morning, while Ard was still in the holding cell for the DWI, Jamie decided he needed all that religion the nuns kept shoving at them. It wasn't long before Jamie went away, studying to be a priest.

The only thing close to right after that had been Rosa Lee. He hadn't made it easy for her, but she had managed to talk her father into hiring him in the Production Control Department at the plant. All he did there was get by; never got a promotion and never wanted one. It was hard enough cutting the weekend parties short in time for Monday morning. Rosa tried, but Ard never thought he had in him what she really needed.

He shakes his head, tries to focus. The report from the fire inspector flashes through his mind, distracts him. It would say what it had to say, one way or the other. What he needs now is to lose the college boys and get back to the baggie in the glove box, back to an answer he's comfortable with.

"Fuck it, man. I'm Arden. Ard for short. You guys wanna go for a ride? I know where there's a cock fight out by the State line." He sees the fear flash in their eyes.

"Thanks, but we probably ought to stick around. We need to hold our table, our wives are meeting us here." Both Guys turn toward the patio.

"Nice meeting you," Second Guy speaks over his shoulder, already heading for his table. First Guy has his wallet out, fishes for his business card.

"If you ever decide to sell the car, let me know," he says. "I'll pay you top dollar. Here's all my numbers."

Ard looks at the card and says "Sure" but First Guy has already caught up to his buddy. He watches them disappear through the door of the bar, looks at the card again, then at the Caddy. It's a choice he's not ready to make, not yet. If the insurance money doesn't come through, maybe, but right now the Caddy's something he can count on, something permanent. The two of them have a nice understanding and Ard can't imagine it any other way. He lets the card drop to the ground and his hand rests on the door handle for a few seconds before he opens it and climbs in.

Ard slides across the seat to the passenger side and drops the glove box lid, digs inside for the bag, glancing out both windows and checking the side view for people. No time to cut proper so he pulls out his license and smashes it hard against the glove box lid, crushing the rocks to powder, running the card back and forth until he's sure its fine. He cuts out two more lines and scoops the last of the powder into the vial. He flips the empty baggie inside out, sticks it between his upper lip and gum and does the two lines.

"Thought you'd gone," Red tells him when he gets back to the bar.

"Some of your new clientele wanted to gawk at the Caddy. Had to scare em off."

"Yeah, ain't like it used to be. Couple of them wanna buy this place."

"Aw hell, Red, you can't sell out. You want me to end up drinking alone?"

"I don't know, Ard. I can't stand this heat no more. Me and Charlene's talking about moving to the mountains. Besides, place ain't been the same since I closed the driving range and Monkey ran off. Little bastard's probably in Mexico by now." Red shakes his head and grins when he says it.

"Why don't you open the range back up?"

"Shit, my heart ain't in it. And you know Charlene wouldn't stand for it after she knocked out my eye with that three wood. Would've been a helluva drive, too. Besides, after that I pulled everything left, and you can't win a bet for shit if you ain't hittin' 'em straight."

"What're they gonna do with the place?" Ard reaches and feels the vial in his pocket, wishes he hadn't asked the question and thinks about going back in the john. Red shrugs and looks at two customers that have just walked up to the other end of the bar, then turns back to Ard.

"You know, me and Charlene, well, she's put up with a lot of my shit over the years. A man needs something, Ard. Used to be, around here, you had a piece of land, some history, you knew folks and they knew you. I don't much think I like it around here no more. Charlene either. She keeps talking about the mountains, Jonas Ridge. I figure I owe her a little peace. At the end of the day, she ain't so bad to sit up in the hills and get old with."

"I still say she hit you with that golf ball on purpose. She always was the better shot."

"Yeah, probably. Having one eye ain't been so bad, though. I don't think I could take it if I was seeing things full on." Red tilts his head toward the other end of the bar. "Let me get these assholes another designer beer."

Ard locks the bathroom door behind him, stands in front of the mirror and gets two quick hits, then leans on the sink and studies his face. He looks older, old, for forty. The blue of his eyes looks more faded, weaker than he remembers. Checks his watch, decides he'll lay out of work again tomorrow. It's been a week and a half, what's one more day? He's probably been fired by now anyway, he hasn't bothered to check messages or call in. Two more hits. Washes his face. Two more. Leans in close to the mirror and whispers "If he sells this place, you got nowhere else to go, nothing left in the world but that damn Cadillac. Christ, you'll have to become a fucking priest."

The bar is nearly full when he returns and Ard is confused. How long was he in the bathroom? The music has changed, it's louder, he doesn't recognize the song. Two girls are dancing together between the pool tables and from this distance the smoke hangs over them like a halo. It seems everyone in the place is talking to somebody and Ard strains to decipher something, anything, that's being said. He makes his way to the bar, but it takes a few minutes before Red sees him. Red's buried shoulder deep in a beer cooler when he yells to him.

"JoJo called and said he ain't gonna make it, Kathy's a little upset about George Bush and he better stay home. What's wrong with GB?"

"Nothing now." Ard shouts back but Red is already passing out more beers.

Ard scans the crowd, thinking maybe he'll spot the two guys that liked the Caddy. The mosquitoes have chased most everyone in from the patio and now the bar is packed. Couples, tables of five, six people, clusters of the upwardly mobile around the bar, turning up drinks, laughing. He doesn't recognize a single face. A guy bumps into him on the way to the bathroom, mumbles "sorry" as Ard elbows him away. Ard sees the car guys at a table in the corner and starts over. They're with their wives, young, good looking, too thin. Ard approaches and raises his beer in salute. Both guys look up, one shouts "Caddy Man!" and leans back into their conversation. Ard waits, then turns back toward the bar, but a redhead already fills his seat, flanked by two guys hovering over each shoulder.

The vial is open in his left hand with the spoon in his right. Ard has no idea how long he's been sitting in the Caddy, how many times he's raised the spoon to his nose, how many people he's watched file into the bar. The din from inside has been replaced by the cicadas and bullfrogs screaming from where the driving range used to be. The noise is deafening and relentless and Ard finally reaches to roll the window up and panics when he nearly drops the vial. What's left will never last until Thursday, won't last much past morning, and a new strain of panic grips him.

It's nearly two a.m. when he pulls into Quinn's drive and rings the bell. He rings, rings again, and sees a glow of light through the window. The door creaks open and Ard is greeted first by Quinn's 9mm, then gradually Quinn's arm, shoulder, and finally half of his face takes shape from behind the door.

"You don't come by without an appointment, shit-fer-brains. What the fuck's wrong with you?"

"Yeah, Quinn, sorry man. Listen I need another eight ball, two if you got it." Ard reaches for his pocket, checks to make sure the cash from Jamie is still there. There's only six, maybe seven hundred left from the bank accounts, and the insurance company won't issue a check until after the fire report. Depending on which way that goes could make for a rough landing. Ard can't think about that now.

"Get the fuck off my porch. I told you Thursday." Quinn starts closing the door. Ard reaches out and stops it.

"You know anybody else that's holding? I got to get through tomorrow."

Quinn steps into full view. He's wearing nothing but his boxers. "Ard, listen, we've known each other a long time, hell, since high school. You gotta slow down, man. Do the drug; don't let the drug do you. You gonna get your ass killed pulling shit like this."

"I got lots going on, Quinn. I need a little more to get through tomorrow, a gram or two even, that'll hold me until Thursday. After that, I should be getting my insurance check. I can pick up some real weight, maybe a brick. Won't be bothering you as often. I'm pretty sure work's canned my ass; it's a lot to deal with, you know? I just need to get by till the check makes it."

"Sure you do. And if the check's so certain, why they waitin' on the report? Besides, you got the last of it this afternoon. My next order won't come in until Thursday morning. And I don't know if you ought to think about upping your count. You gettin' a little carried away lately. Now I got to get back to bed before Annie gets up. Go home, go to bed, leave that shit alone for a day. I'll see you on Thursday."

Ard stands beside the Caddy and stares into the dark sky. He's surprised that he suddenly remembers a class from high school and Mr. Hoskins talking about black holes. About how once something is drawn into one it's never released, how it becomes anti-matter, as if it never even existed. Ard searches the sky and thinks about the absurdity of it all. If nothing exists in a black hole, then how can anyone know the holes actually exist? You can't measure empty. Ard stretches both arms upward and gives the Milky Way the finger.

***

"A threat. You come to my house and deliver a threat? Okay, sure, I'll drive. Maybe before we get to the bishop's office we'll make another stop, see how the sheriff's doing." Jamie doesn't turn to face Ard; rakes a comb through his thinning hair.

"Come on, Jamie. Just let me have a gram or two. I'll make it up to you after I see Quinn tomorrow. Besides, you gonna tell the sheriff old Ard here's been selling you cocaine? Remember, I'm out, I ain't holding, what're they gonna do?"

Ard can see the priest's reflection in the mirror but Jamie doesn't return his gaze, occupied instead with adjusting his collar. Ard looks closer at his brother's image. Same blue eyes, but stronger. Jamie's chin is his chin, Jamie's nose, his nose. Ard thinks of his best friend from childhood, the boy he grew up with, hunted and fished with, drank his first beer with. Thinks of how he loved him, how he hated him, and he suddenly realizes of all the assholes walking the earth, Jamie's the only one with the same blood in his veins as his. So what was it Jamie had that he couldn't find?

"Today would've been your and Rosa's what, fifteenth anniversary?" Jamie says as he turns to face Ard.

"Fuck you, Jamie. Why you gotta bring that up?" Ard walks out of the bathroom hallway and sits at the table. Jamie follows him.

"How long since you've been to work?"

"I don't know. Week, maybe more." Ard rubs his eyes with the heels of both hands.

"Have they fired you?"

"Yeah, probably. I ain't bothered to call."

"Arden, you can't just not work, you've got to get your shit together."

"The fire report's due this week. I'll have the insurance money in a couple of days. Now come on, Jamie. I feel like shit warmed over." Ard drops his head on the table. The laminated wood lies cool and foreign against his forehead.

"So take the money and start over. Get yourself straightened out. Our church has a program…"

Ard jerks his head up from the table. "So is this advice coming from my cokehead brother or the local cokehead priest? You don't know shit, Jamie, you never did. Jesus Christ, we weren't even fucking Catholic. Our old man a drunk. And hell, if the State hadn't of sent us to the home after Momma died, you'd never of seen the inside of a church. You were the dumb ass that bought into all that shit they fed us. Look at you, you're no different than Pop, no different than me. Use your own damn rehab clinic."

"No. You're wrong, Ard. I thought about what you said yesterday, what we talked about, what I'm doing. Becoming. Thought about it a lot. Maybe we aren't any different, maybe you're right. But I've found my place, what's right for me. Not this. So can you. Love…

"Save the bullshit, Padre, I know the routine. I heard all the same fairy tales you did, but I ain't stupid. Look around, take a good look. God is great, God is good—you remember when we had to say that blessing? My ass. Your God is one twisted, vindictive SOB the way I see it. Damn Jamie, you're a fucking priest and you're doing an eight ball of coke a week."

"No. Not any more." Jamie turns and stares out the kitchen window for several minutes and Ard can feel the air disappearing between them, finds each breath more difficult. When Ard hears the sound of Jamie sliding open the kitchen drawer he can feel the oxygen rush in to fill the space. Jamie faces him and tosses the eight ball of coke. It lands on the table and slides across the laminate, nearly falls off into Ard's lap.

"I'm done. Never even opened it. There it is, now you make a choice. We're brothers, Ard, we'll walk away together."

Ard looks at the bag, can already feel the surge and his heart quickens. He pauses for only a second before slipping the bag into his pocket.

"Cash is a little tight. Okay if I square up with you after the insurance check comes in?"

"Don't bother."

"Really, man. I'll cover you, swear it."

"No." Jamie shakes his head and looks at his shoes, sighs and walks past Arden toward the door. Ard feels him pause just behind him but he can't turn and face his brother, even as Jamie speaks to him. The words "I love you" filter over him but Jamie's voice sounds a thousand miles away and echoes faintly until Ard hears the soft click of the front door.

***

Outside the sky has already gone white from the stale heat and humidity and it'sonly ten in the morning. The steering wheel is hot to the touch and Arden uses the heel of his hand to guide the Caddy into the street, not sure where he is going. He rides past his apartment, turns around and comes back, this time pulling into his parking space. He stares at his balcony window, thinks the Caddy is the only place that feels like home as he lightly touches the bag in his shirt pocket, then backs out.

The parking lot at Red's is empty and Ard makes a wide turn, cuts the wheel hard left and throws a spray of dust and gravel toward the patio before coming to a stop. As he's walking down the overgrown path behind the building, Ard decides there's no sight more depressing than a bar in daylight. When he reaches the clearing he stops beside the wooden picnic table and stares first at Monkey's empty cage, then the table. He thinks of the night he talked Rosa into doing it right there on the table and how Monkey screamed and rattled his cage the whole time. The scent of patchouli drifts up to him and he reaches to let his fingertips trace along the edge of the boards where Rosa, smiling, had pulled him toward her that night. Ard suddenly spins and kicks the cage with his right foot and nearly falls as it rocks back on two legs. He kicks it again and this time it tumbles into the weeds, the door pops its rusty hinges and swings free, slamming into his shin. Ard pulls up his jeans and watches the blood trickle down his leg until it reaches the top of his sock.

The inside of the Caddy is almost unbearable now and Ard can feel his shirt sticking to the back of the seat as he picks the cockle-burrs and beggar lice from his pants. His leg aches and the AC's blowing hot air, the last of the freon gone. He looks around the empty parking lot, at the bar, at his reflection in the rearview, but only for a second. He takes the baggie from his shirt pocket and holds it up to the sun. He moves the baggie in front of his eye, further, then closer to his face until the bag blocks the ball of sun from his view. He reaches to open the glove box but slips the bag back in his pocket instead and drops the Caddy into drive.

Ard slows down as he passes JoJo and Kathy's place but he knows nobody's home. Before he realizes it, he's covered the two miles and is parked in what used to be his drive. He wishes the big oak were still there but the flames jumped from the house to the branches and then it was gone too. The weeds and briars have taken over the twenty-three acres to the point that even the real estate developers that have started calling don't realize there was a house there only six months earlier. Ard walks past where their porch once stood, through the remains of Rosa's flower garden. The sun's nothing more than a glare in the sky and everything in front of Ard appears to shimmer and he can see the waves of heat rising from the earth.

The dry weeds crunch with each step Ard takes and for a moment the sound reminds him of walking on snow. He can hear the insects buzzing and occasionally sees a grasshopper take flight as he approaches. The dog days. The time of year when you can smell the heat, and, when he was a kid, this was the time you'd see some stray dog come wandering up, its head low and swinging from side to side as it ambled forward, slobber and drool dragging from its jaws. Step after stiff-legged step, it would just keep coming at you like it wanted you, needed you to take the twenty-two from the rack and put a hollow point through its brain.

Ard keeps walking, covers the ten acres they planned to turn into pasture, passes the faded barn and its empty stalls. The land rises slightly here and the uphill steps shorten his breath. At the crest of the knoll Ard stumbles and falls to one knee, but catches himself before landing on his face. The pond is at the bottom of the hill only twenty or thirty yards before him and as he rises to his feet, the green water looks thick and solid.

There's no shade anywhere and Ard sits on the low side, opposite the dam. He takes the bag from his shirt pocket and begins to unwrap the twist tie when he hears a voice behind him and quickly drops the baggie, still open, back into his shirt pocket.

"Those aftermarket AC's never work on Caddy's, huh?" The boy, about nineteen or twenty Ard guesses, stands over him. Ard doesn't recognize the boy. He can tell he's wearing fatigue pants and no shirt, but the sun distorts his view of the boy's face.

"Hotter than a French whore in Saigon, ain't it?"

Ard looks back at the pond, wraps his arms around his knees.

"I come down here for a swim, little R & R. How about you?"

Ard looks back at the boy but the sun is directly behind him now and he still can't make out any of his features. He's nothing more than a dark silhouette and his shadow stretches over Ard, but Ard doesn't feel any cooler. He shades his eyes but the boy still doesn't come into focus.

"Fire's a helluva thing, ain't it? Cook your meat, burn your house."

"Who the fuck are you?" Ard tries to get up but his legs have fallen asleep and he has to roll onto his knees and then tries to push himself up but can't.

"Napalm; now that's a fire."

"Get off my property."

"Fire'll burn itself out. This heat just keeps on, don't it?" The boy shifts to one side and the glare of the sun blinds Ard and he quickly turns his face away.

"Need some rain," the boy says, drags the toe of his boot in the packed dirt. "I heard there was a house up yonder. Burned down first day of March, what I heard."

Ard tries to stand again but his left leg is still stiff and heavy, feels like it's separate from his body and he raises on his good leg while he rubs his hand over his other thigh, trying to get the blood moving.

"Guess they coulda used some rain that day too, huh? Mighta been able to save the woman what was in the house to slow that blaze some. Well, shit like that'll happen, can't say the reason why. Coulda been her husband was trying to cook up a little hash oil. You look surprised there, brother. Ah, I know all about that. Take a little hooch, mix it in with a couple of buds and boil it down. I seen it done in a field helmet, though, never on a stove or nothing. You got to tend it close either way, that stuff'll flame up in a second. Course, it coulda been some bad wiring, it was an old frame farmhouse and you know how those are. Tinderbox, and probably ain't no insulation on the wires, house that old. You don't ever know."

"Bastard."

"Something like that get in a body's head and just eat away, best not to even dwell on it. I seen plenty I ain't got no answer for. Seen this VC come running across a field and a 50 caliber cut him plum in half, right at the waist. His legs just kept on running like ain't nothing happened. Heard this thump one morning right beside of me. Looked over and damned if my best buddy's head wadn't gone and him still holding his rifle. Go figure."

"I said get off my property." Ard's teeth are clenched, the muscles along his shoulders taut.

"Course I guess that VC and my buddy was both just trying to hold on to something. Bout like the old man used to have that Caddy. The answers don't matter one way or the other. Just like that old car, none of it really stands for no count, huh?"

Ard lunges at the boy, swings wild but the boy glides out of the way. When the boy turns, Ard can finally make out part of his face. The features are blurred and for an instant he thinks its Jamie, even calls out to him twice, but the boy shows no sign of recognizing the name.

Instead, the boy looks across the water and stretches. "Damn hot, ain't it? You know, if I was you, I'd go on and sell that Caddy. After market AC won't ever be right, no how. Ain't no point thinkin' it will." He stretches again and cocks his chin toward the pond. "Yep, think I'll take that swim now," he says, then runs past Ard and dives headfirst into the water, barely making a splash.

The ripples spread across the pond and Ard waits for the boy to surface. The last of the tiny waves reach the far bank and still no sign of the boy. Ard calls out to him, begins to panic, yells again. Wonders why the boy looked like Jamie, only for that second, and the thought tightens his throat. He looks around, half expecting to see someone, anyone, that might help but he's alone and his voice echoes against the trees at the far side of the property.

In an instant, Ard breaks for the pond and dives just as he reaches the water's edge. The water rushes over him and he's amazed at how cool it is, how he can feel it gliding over every inch of his skin. He strokes twice, three times, heads for the deepest part of the pond, but he doesn't see the boy anywhere. He turns all the way around, looks everywhere but sees nothing in the murky water. Ard dives deeper still, finds the muddy bottom. Nothing. His lungs are aching now. He opens his mouth and yells but the only sound is his heartbeat. He turns around once more and then he no longer feels the water on his body, forgets about his empty lungs.

The water around him is clearer now and he sees a shadow floating near him. When he moves closer and tries to grab the form it's gone. He realizes he is screaming and as he feels the water rush in his lungs he's certain he smells wood smoke. Ard looks up, calmer now, and sees Rosa Lee smiling and slowly moving toward the surface. The baggie floats out of his pocket and hovers in front of him, the cocaine briefly clouding his view of Rosa before it dissolves into nothing. When the water clears again he can only see the yellow sun perfectly formed above him, its rays soft and light, cascading through the water. Ard rises toward it and as he breaks the surface the air washes over him, carrying the clean scent of jasmine across the pond.

March 8, 2012

Razor Dance, poem by Wendy Ellis

Bill stood in his socks a thousand times

before this dimpled mirror–

at this pitted, stained sink

with its small rubber plug on a little, coiled chain.

Bill's straight razor rested across the top

of a heavy ceramic shaving mug.

The mug held just enough

shaving soap for one more close shave.

A nail held a Pullman strop, curved with age and use

above and beside the sink, and he'd knock it

with his elbow when he pulled his cheek high

to carefully scrape the whiskers away.

He'd stand there, soapy and deliberate–

and a whistled phrase from the 'Chicken Reel'

would slip out between his pursed lips.

His right arm would hesitate, then Bill would fling out

his hand and he'd do a shaky bit of clogging. Flat-footing

in the bathroom with that razor in his hand.

No taps, no wooden soles–just his socks

on the bathroom floor. Jigging as the sun came up

and the coffee brewed downstairs.

The floor sighed under his feet,

the house knew Bill was reeling and whistling–

swearing delightedly as he reached for a styptic pencil

to staunch the nicks.

He'd drag-slide, loose kneed

across the room, pull on his boots,

whistle under his breath, come down the stairs.

Swing his wife around and leave for the woods,

coffee hot in a thermos under his arm.

March 5, 2012

Poems by Karen Lockett Warinsky

Tough Girls

We were a little afraid of those girls–

tough girls in our town–

the life they came from.

Lank hair, wiry bodies with taut faces,

expressions hardened by scant meals,

their eyes plunged through ours

as they sized us up,

black liquid eyeliner worn like warpaint–

a warning:

"Don't fuck with me," it said.

By 14 they knew things we did not:

Cornflakes could be eaten for supper.

Clothes could be washed out in the sink with

a bar of soap.

Swiping a lipstick or some gum

from Glidden's Drug Store

was pretty easy; that you could cry

and hold your breath

at the same time.

They could get the coat and boots off their dad, and put him to bed.

They learned where their mom kept her money stash and cigarettes,

when not to let the neighbor boys in the house, and how to

turn an uncle's old jacket into a fashion statement.

As high school rolled on we noticed

them dropping away, petals from a wilting flower.

No longer in class—no longer in the bleachers at games—

no longer haunting Main Street with their cimmerian eyes.

Some Nights

There were ways to survive it–

small town life. It required shoe leather,

empty basements with record players and a couch,

Boones Farm, a six pack, some smokes;

John Prine, Linda, Bob and James to sing us what was real.

It required thermoses full of sloe gin fizz,

shrimp baskets from Robert's Drive Inn,

Monty Python at 10 p.m. on Sunday,

the carnival every June, part-time jobs.

We had been to church; were baptized and

confirmed. Did good up to a point. Then we

awakened to our dad's dead end jobs and our

mother's endless desires for a new car, a new winter coat

and a finished basement; their longings for

paved driveways they could ride on into society

weighted down our hearts.

We weren't sure what that meant for us,

but the time clock in the factory taught us our worth.

And some nights we climbed up on the hood of the car,

watched the sun go down into the cornfield

and planned our escape.

Karen Lockett Warinsky is breaking out of her routine as a mom and a high school English teacher and wants to write more about small town life, living in Japan, the vagaries of love, and all the ironies of life that have come her way. She was a semi-finalist in the 2011 Montreal International Poetry Contest, and is currently a mentee with Arc Poetry Magazine. Two of her poems will appear later this year in Joy, Interrupted: An Anthology on Motherhood and Loss, published by Fat Daddy's Farm. Ms. Warinsky grew up in Northern Illinois and holds a Bachelor's in Journalism from Northern Illinois University, and a Masters in English from Fitchburg State University in Massachusetts.

Karen Lockett Warinsky is breaking out of her routine as a mom and a high school English teacher and wants to write more about small town life, living in Japan, the vagaries of love, and all the ironies of life that have come her way. She was a semi-finalist in the 2011 Montreal International Poetry Contest, and is currently a mentee with Arc Poetry Magazine. Two of her poems will appear later this year in Joy, Interrupted: An Anthology on Motherhood and Loss, published by Fat Daddy's Farm. Ms. Warinsky grew up in Northern Illinois and holds a Bachelor's in Journalism from Northern Illinois University, and a Masters in English from Fitchburg State University in Massachusetts.

March 2, 2012

Mama's Last Love Song, poem by Joe Samuel Starnes

The sun goes down and it gets cold.

Our children are behaving like dogs.

The snakes are sleeping deep in their holes,

fiery red and orange has faded from the leaves

and our cups are brimming with bourbon.

A blue sky is slowly settling to dark.

I escape the house out into the field after dark.

I've forgotten my coat and shiver cold.

In my pocket I've got a flask of bourbon.

In the distance I hear your wild dogs

barking and crunching in the leaves.

I'm watching out not to step in gopher holes.

Across the road I hear a shotgun blast holes

into a road sign or beer cans lined up in the dark.

The wind back and forth flutters the leaves.

My hands and feet are numb with cold.

I'm glad to be ignored by your dumb dogs

who rely on warmth of fur instead of bourbon.

No winter coat can warm me like bourbon

and fill up the many lake-sized holes

in my heart not filled by the love of a good dog.

I walk to the big oak and stand in the dark.

My dog froze to death last year in the cold.

You buried her somewhere under these leaves.

I wish I could go but I can never leave

so I stand here sipping this warm bourbon,

my only protection from loneliness and cold.

My mind is turning into a sinkhole.

I paw my shoe at the earth brown and dark.

You love me much less than these dogs.

Our children take after you and the dogs,

rooting and scrounging in the leaves.

I wish they would fall down into a deep dark

well and get stuck; I'd drink bourbon

gazing, laughing down into the hole,

not giving a damn if they were wet and cold.

I'm out of bourbon and getting cold.

The dogs are dashing through the leaves.

Tonight I'll take down your gun and shoot holes in the dark.

Joe Samuel "Sam" Starnes was born in Alabama, grew up in Georgia, and has lived in New Jersey and Philadelphia since 2000. NewSouth Books published Fall Line, his second novel, in November 2011 (view the online book trailer). His first novel, Calling, was published in 2005. He has had journalism appear in The New York Times, The Washington Post and various magazines, as well as essays, short stories, and poems in literary journals. A graduate of the University of Georgia and Rutgers University in Newark, he was awarded a fellowship to the 2006 Sewanee Writers' Conference. He is working on an MFA in creative nonfiction at Goucher College.

Joe Samuel "Sam" Starnes was born in Alabama, grew up in Georgia, and has lived in New Jersey and Philadelphia since 2000. NewSouth Books published Fall Line, his second novel, in November 2011 (view the online book trailer). His first novel, Calling, was published in 2005. He has had journalism appear in The New York Times, The Washington Post and various magazines, as well as essays, short stories, and poems in literary journals. A graduate of the University of Georgia and Rutgers University in Newark, he was awarded a fellowship to the 2006 Sewanee Writers' Conference. He is working on an MFA in creative nonfiction at Goucher College.

February 29, 2012

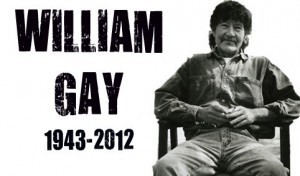

The Great William Gay

has died, but will not be forgotten.

has died, but will not be forgotten.

These are some well-known facts in William Gay's official biography: that he lived in a cabin in the woods, that he didn't use email, that he worked in construction his whole life until someone finally noticed he was a great writer. But these facts tell only part of the story.

For readers and writers, at least, the fuller story depends upon an eternal question: is a writer born, or is he made? William Gay was born a writer. As a late-life literary success who didn't attend creative-writing programs or pay for professional workshops, Gay symbolized the hopes of struggling writers, especially rural ones. He was good, and he found a way to let the world know he was good—those are facts we cling to as evidence of what is possible. Throughout history, people have made long pilgrimages to witness lesser miracles.

William Gay's death last week of heart failure sent tremors through the community of writers and readers in Tennessee and beyond, people who loved him as a friend and as a writer. We have asked some of those who knew Gay, in ways large and small, to send us their stories. They come from New York City and from Wyoming, from Maine and from Virginia, and, of course, they come from Tennessee. Together, we hope these recollections—from Darnell Arnoult,Adrian Blevins, Sonny Brewer, Tom Franklin, Robert Hicks,Derrick Hill, Suzanne Kingsbury, Randy Mackin, Inman Majors, Corey Mesler, Clay Risen, George Singleton, Brad Watson, and Steve Yarbrough—present a portrait of a man who will be greatly missed.

February 28, 2012

Cat Killing, fiction by James Alan Gill

Every time I tell this story, about me helping Charlie McMaster kill a whole passel of cats, people tend not to believe it. Maybe it's that they can't imagine real people living this way, and for that I can't blame them, because no person should have to live a life like Charlie had to, but he did, and still does, and there's no changing that.

So when I finish here in a bit, and you walk away saying I hope that ain't true old man—thinking I'm sick in the head; thinking about them poor little kitty cats—well then, the fault's all mine in the telling. Maybe that's why I keep telling it, thinking that if I can get the wording down just so, people will somehow understand. The facts are all there. So let me see if I can set them straight for you.

Now the cat problem first started with three—a bobtail black-and-white and two calicos—but by the time Charlie called on me, the feline head count had grown to thirty-seven not counting kittens, and a person couldn't walk from the weedy driveway to the old house, a distance of no more than twenty feet, without stepping in rust colored catshit. So when he came walking down the hill late one Saturday morning and asked for my help, I went right in and put on my coveralls, because the thing about Charlie McMaster is he's the hardest working man I know, and he never asks for help unless he truly needs it. His own family never offered him as much. Hell, I've known him to drop everything to drive forty-five minutes one way just to help his mama do things that are so simple as to not need any help, and if they were complicated, it could usually wait till the weekend. But still Charlie comes running. That's the kind of man he is. And yet there's some people around here that think he's a traitor to his own for his moving out of the county trying for something a little better. Of course, those people wouldn't know shit for kiss-my-ass.

So while I was lacing up my boots, he started telling me his plans on how to finally make the family farm productive, clean it up and find something that would be low maintenance, maybe bring in a little money for his mama. Mentioned turning it into a Christmas tree farm, or planting it to hay, or just letting it all go back to trees, any of which would be better than its state for the past sixty years.

_____

When Charlie was little his grandpa Homer raised pigs on the place, not by choice but because the hog lot and the livestock came with the price of the house. When the old man died, Charlie took over the care of the pigs even though he was only eleven years old, and things ran smooth enough all things considered, but then, when he was just starting high school, cholera broke out and every last one of those animals had to be destroyed. And if that weren't bad enough, it spread to a neighbor's farm, and they had to do the same with their pigs, and there's been bad blood between them since.

Charlie's uncles—Tuffy and Jess—had never cared nothing for hog farming, leaving the chores first to their daddy and then to their nephew, and so instead of trying to buy more stock or try raising something else or even to make amends with the neighbors, they just kept on with their so called salvage operation and covered the forty acres with junk, never considering who was going to clean it up.

You see, when the uncles both came home from the war, they never said a word about what they'd done or seen: Jess having been captured by the Nazis only to escape and run smack into the Italians, spending the last days of the war in a hospital watching out the window as Mussolini was strung up by his ankles outside; and Tuffy pushing his way through constant fighting in France and Germany only to see even worse horrors when the concentration camps were liberated—no, they never said a thing, just arrived back home one day in 1946 as if they'd been in town for the weekend, and soon they started frequenting auctions with their Army pay and their father's same sense of a good deal, and they bought up any and every thing, including boxes of leftovers that no one else wanted.

Their old man made them keep things in order while he was alive—no junk lying about the yard or fields—and Mrs. Thompson kept that house slick as a button, but in a few years, old Homer died, and in a few more so did his wife, and then the cholera killed all the pigs, and the junk kept collecting in the barn and along the drive and over into the empty hog lots, a wealth measured in things but not in value: old wooden-handled tools, school desks, fifty two rusting car bodies, a leaky boat, a dragline with a blown engine bought from a bankrupt construction company, crates of license plates, shelves of player piano rolls, scratched records and later eight track tapes, a ten by ten pallet of books no one would ever read again, and that ain't even half of it.

I don't know. Maybe at one time it all could have been worth something. But now it was nothing but a blight.

_____

With all this laid out in front of him, Charlie was excited about the prospect of finally making things right. We walked down to the farm to look things over, Charlie still full of possibilities, then went in to Mrs. McMaster's kitchen table for a cup of coffee, and in passing conversation, Charlie's mama told him she'd counted over thirty cats gathered when she took food out that morning. Now a farm always has cats on it, and I don't think Charlie would have minded a few, but when she told him she's spending near a hundred dollars or more a month on cat food, ole Charlie nearly lost it.

He told her, stop feeding them. Said, if you keep feeding them, they'll keep coming back.

Well, she said, Leila won't let me.

Leila was her youngest sister who still lived with her, same as she always had her whole life, though now she had Oldtimers disease and was crazy as a shithouse rat.

His mama said, I'm afraid that if she woke up one morning and the cats was gone, she'd get real upset. You talking about tearing down the house is hard enough.

Charlie snickered, said, in a few weeks she won't even remember there was any house. Or any cats for that matter.

Well his mama nearly come out her chair. Said, Charles Woodrow McMaster, I can't believe you just said that.

But Charlie had grown impervious to his mother's guilt over the years, and said, I can't believe you're feeding three dozen cats.

Now this makes Charlie sound like a hard sonofabitch to be talking to his mama and his batshit old aunt like that, but if a person knew how he'd come up, they might think different.

_____

Charlie spent his first seventeen years in that house, living with his grandparents, his mother, her two brothers, and Leila, because his father had been killed by bootleggers when he was eleven months old. And they'd lived as poor as people can live. No running water. Charlie never had a bed till he was married. Always slept on the floor between his two uncles' beds in their room. When he was a kid, he never got meat at the table—uncles would eat it all up and tell him he could chew the gristle if he wanted a taste. But it was no secret about how stingy Charlie's uncles were.

Hell, even as a grown man, the few times Charlie would ask his uncles for something he needed—a car part or a tool, which they usually had lying around one of the outbuildings or just sitting in the lot taking on weeds—he always paid them for it, because them old boys had never give anyone anything their whole lives. Still, no one understood their selfish greed completely till they finally died fifteen months apart, same as they'd been born, and Charlie and his mother were given control over the brothers' bank accounts. You can't imagine their shock when the balance came in at just over a hundred thousand dollars. Sounds like a lot, but all it shows is that they saved two thousand a year and never spent a dime on anything but the junk they hoarded. Charlie's mama bought all the food and Leila paid the utilities. Thinking about it makes me want to spit fire.

It was from all this that Charlie realized his only chance was to work. And work he did—as a hand all year round for a farmer a few miles south of here; had a hay crew in the summer; and still he slopped hogs and kept up with his school work. But the one thing that stood out was that Charlie had a way with animals, and in his first year of high school, he got a job cleaning cages, helping out at the veterinarian in town. And the doc there encouraged him and taught him the work, and so Charlie thought that's what he'd try to do. He even applied to a school for it, and would have been a damn good one, if he'd had the chance.

But the chance never came. So he kept working. Got on at the power plant over the river inIndiana, married a girl from there, and believed he'd never bother with the farm again. But before long he was coming back regular to help his mama around the house, because his uncles never did a thing except what they wanted anyway. Seems no matter how you try, you can never really get away from this place.

Shit, I know that all too well. During the war I left to work in the Lockheed plant inBurbankCalifornia, stayed on there for almost ten years, but when our son was born in 1951, just a year before Charlie came into the world, and our oldest daughter was getting ready to start school, my wife and I figured we ought to be back closer to home. So we packed up and moved into this place and that's where we've stayed. Maybe it was the right thing to do. Maybe it didn't make a difference one way or the other. But even now, I can't help but think about being able to draw that Lockheed pension or how much the house inTolucaLakewe'd bought for eleven thousand dollars would sell at today. But the past is past. And besides, I chose to leave and I chose to come back, and that's worth a whole hell of a lot. Charlie sure as shit never had that pleasure.

_____

Now a person might wonder at how people find themselves in such a life as Charlie's, for surely things hadn't always been this way, and they'd be right, as his people hadn't been junk traders or hog farmers on this hill for all that long. No, Charlie's mama and aunt and uncles had been born river people over on Skillet Fork, and his granddad, Homer Thompson, made his living running trotlines for buffalo carp and catfish which he could trade for sugar, flour, cornmeal, and coffee at the market in town. Outside that, they lived from their garden and whatever game they could kill in the woods and of course whatever Homer brought in from the river.

Once old Homer told me about the time he came upon a blue heron caught in one of his lines, probably drawn to the thrashing of the live bluegill he'd put on as bait hoping to draw in a big flathead. But it didn't matter to that man what creature was on the hooks, and he took that skinny stork home to his wife, had her cook it up, and God help you if you complained about that tough stringy mess he tried to pass off as meat. He never gave any thought about another way of living. Things were the way they were, and that whole family would probably still be on that river now if Homer hadn't stumbled onto what he considered the deal of the century.

The farm is set on a little rise called Pig Ridge about six miles south of Matin, named for the fact that the place had been the site of a hog lot since the late eighteen hundreds, and so it was in 1939, on one of his trips into town, that Homer found the place up for sale at a bargain price.

The new house was all but completed, with one room left unfinished because the man who'd started building it the year before ended up hanging himself from the rafters after he sent for his wife and three kids at her mother's house up north. Some say that she refused to come down here and live on a pig farm, and others say she was had another man, which very well could have been true as she remarried to a banker within the same month of her husband's death, but whatever the truth is, it's known that she didn't come to Matin County for the funeral, and she must not have needed the money because she put the farm up for sale where it stayed nigh on a year because no one would buy knowing a man had been driven to suicide whilst building it.

But Homer Thompson didn't care about dead men, only good deals, so when the newly wedded widow grew tired of waiting and lowered her price to ten dollars an acre, Homer jumped on it and bought the house and forty acres, including the hogs that were already living on the farm, for 400 dollars even, money he drew from a tobacco tin stuffed beneath the floorboards of the cabin. His family never questioned him on where the money had come from, and they didn't really care because just the thought of leaving life on the river was better than any earthly riches.

Homer moved in with his wife and four kids, and within a few years his sons went to the army and fought in Europe and came home again, and then in a few more years, Charlie's mama met Wibb McMaster and they ran off and got married.

But on the day Charlie came into the world, Wibb was spending time in jail awaiting trial for stealing cars. Charlie's mama stood by him even though she'd been disowned by her family and couldn't go anywhere in town without hearing the unquiet whispers of people as she passed. Wibb was finally acquitted when the man whose car had been stolen suddenly remembered that he'd agreed to loan him the car. The prosecutor figured the man had been threatened or that he was in on an insurance scam but couldn't come up with the evidence, and Wibb was a free man.

Still, he never spent much time at home, would take off for two or three days at a time, then come home to his teenaged wife, and she'd cook big meals and fuss over him and they'd have a honeymoon of sorts, and then a week later Wibb would be off again. It was one of these excursions that finally did him in, and instead of Charlie's wayward daddy returning home, the county sheriff came calling with the news that he'd been killed when a car ran off the road and up into the yard where he sat drinking homemade whiskey—a yard belonging to Blackie Harris, who in later years would become the oldest man to make the FBI's most wanted list for killing his girlfriend and the man she was with and burning the house down around them to cover it up. The string of crimes and killings that filled the years before that had somehow slipped through the cracks, much like Wibb's trial when Charlie was a baby.

There was a court trial over Wibb's death, but in the end it was called an accident, even though the driver had to drive three hundred yards off the road between a row of silver poplars lining the driveway to hit him. Eight days after the trial ended, Homer Thompson came to the rented room where his daughter and grandson were staying, and he packed up all their things without a word and brought them back to Pig Ridge as if nothing had changed, and that's how Charlie came to live there.

He didn't ask for none of it. I guess none of us ask for the lives we're born into, and none of us are born into perfect lives—we all just make the best of it, some better than others—but it's amazing to me that a man such as Charlie McMaster could come out of a bullshit situation such as that. I can't rightly say that I'd have been able to do it. I guess it all boils down to whatever a person uses to forget the lot they've drawn: booze or women or meanness or hoarding things away. Charlie chose hard work and kindness and selflessness, and it was all of his own doing because there wasn't any goddamn role models around for him to learn it from.

_____

So now Charlie was the only man left in the family and saw it as his chance to make a reckoning with this place. No uncles or wayward fathers to stand in his way. First thing he did was took his uncles' money and bought a brand new double-wide trailer for his mama and Leila and set it fifty feet behind the old house where they'd lived for the last sixty years. Then he bought a used backhoe and started to plan on how to clean up that mess of a farm, which was his only legacy. And that's when he came down to see me.

On the morning of the cat killing, I kept watch from the front window of my house. Charlie had worked it out with his mama that when she took his aunt Leila into town on Saturday for grocery shopping, he'd kill as many cats as he could while they were gone, and they'd both act like nothing happened.

Around eight in the morning, Mrs. McMaster left for town with Leila in tow, and when the car had gone below the hill out of sight, I picked up my guns and walked down the road where Charlie stood in the driveway. He was smiling, like he usually was, plastic mug of coffee in his hand, cigarette in his mouth.

You ready to kill some cats, he said.

I said, I'm ready to help you out.

We laid our guns in the bed of his truck. He had a single shot twelve gauge he'd found in his uncles' bedroom, and I pulled out the Belgian Browning that I'd always used bird hunting along with a small twenty-two bolt action with a scope.

I said to Charlie, what's your plan?

Well, he said, I figured we'd set out some milk, get them all together, then start shooting.

And that's what we did. He went into the trailer and brought out a gallon of milk and three plastic bowls, old butter containers his mama'd washed, and set them on the bare dirt between the old house and the doublewide. Then we stood back under the porch and waited.

Soon the cats started to crawl out from everywhere. They were feral and vicious. The younger cats ran to the milk, but the older cats, led by the bobtail, stood back, lurking out of sight. We just sat waiting, and after a while, they moved in slowly, like they were stalking something. As they neared one of the bowls, the other cats skittered away, all but one, and now the two calicoes flanked in from each side and that ole bobtail came up the middle. It's terrifying really, to watch domesticated animals that are usually curled up in someone's lap latch onto another's neck with teeth and claws till it hobbles off trailing blood.

Before long, each bowl of milk was surrounded by cats, and Charlie and I walked slowly from under the porch of the old house and each of us raised a shotgun to our cheeks and stood for a minute. It was odd, almost ceremonial, like a firing squad, and I was waiting for Charlie to start counting or say fire, some kind of signal to begin, when he pulled the trigger on his twelve and my ears went deaf with the ringing. Two cats lay twitching by the milk. Another darted away to the right, and without a thought, I put the bead on him and let fly. The cat flipped ass over tea-kettle and landed in a heap.

Two shots and there wasn't a cat to be seen. I walked over to Charlie's truck, laid down my shotgun, and picked up the twenty-two. Charlie broke down his gun and slid the empty shell from the chamber.

He said, I saw another one go around the house. See if I can't flush him out.

I slid up onto the tailgate of the truck and said, I'll be here.

He made a wide circle around the back, and I watched the opposite side, like you'd do rabbit hunting, expecting to see the animal edging along fifty yards ahead of the dog. But cats ain't rabbits.

I turned to look at a large pile of scrap metal along the edge of the driveway, scanning for any of the cats that might've holed up in there, when Charlie's gun boomed, echoing off the tin-sided barn, and I turned to see a cloud of white fur drifting across the lot like a giant dandelion had been blown off its stem.

I called out, I think you got him.

Charlie appeared holding the carcass by the hind legs. The cat's head was turned inside out, nothing but blood and meat and teeth. He threw it down amongst the other dead still lying by the milk bowls and said, you know, I never killed anything that I hadn't intended on eating.

The skin round his eyes was lined, like he carried the weight of death itself.

Well, I said, smiling at him, you can eat them if you want.

Then behind him I caught a flash of movement and saw a tabby cat slide behind an old storm window leaned against a rusted trailer frame. I raised the rifle, and the cat poked his head out just a bit, careful and waiting, and when the crosshairs fell on the cat's neck just behind its jaw, I squeezed the trigger, and it dropped in its tracks.

Was it that bobtail? Charlie said, hopeful.

No, I said, just a tabby.

He spit into the mud and said, I hate that goddamn bobtail. Took up residence under the trailer right after we put it in and tore the insulation off the pipes and they froze. And you know who had to drive over here and thaw them out when it was seventeen fucking below zero.

We waited a while, and Charlie lit a cigarette and thanked me again for being such a patient neighbor, said that most people would've called the county or the EPA and forced a cleanup regardless of cost. To be honest, it'd never crossed my mind to do that. I could see the state of things when I moved in up the road. I guess if I didn't like it, I could've found another house. Maybe like Charlie's granddad, I was willing to put up with a few things in return for a good deal.

After half an hour, we still hadn't seen another cat. I went and picked up the dead and carried them into the field. I figured we'd just take them out away from the house and leave them to the coyotes and buzzards, but Charlie started up the backhoe and went to digging. Now a lot of people who know Charlie would of laughed at this, figured it was part of his crazy nature: a mix between a childish fascination for heavy equipment and a tendency toward overkill. But that wasn't it. At least I don't believe it was, because I saw the same thing a week later when he tore the old house down.

_____

Charlie had planned to spend every Saturday for the next year cleaning up the farm. At the time I didn't see any reason for him to be in such a hurry, but it's clear to me now that as long as that old house stood and that farm lay covered in junk, the memory of his old life stood with it, and I guess he thought that when it was gone, he'd be shut of the past as well.

That next Saturday, I waited for his mama to leave with Leila same as before, then walked down where Charlie was chomping at the bit. We started going around to each window on the old place, removing all the glass, which I guess was a gesture of safety and sensitivity to the fact that Charlie was getting ready to destroy the only house the living members of his family had ever known. After he doublechecked that the gas and electricity were turned off, we went inside one final time.

Six rooms: the kitchen with its big porcelain sink, the main room with the gas heating stove, the three small bedrooms built on, the bathroom which had been added in the mid-eighties when Charlie's uncles finally gave into the idea of spending the money to bring in running water. In the room that had been his mama's, there was a giant hole in the plaster, stuffed with an old quilt to keep out the draft. This is where she'd slept only a few months before.

He'd wanted to tear the house down with everything still in it, but Mrs. McMaster had refused, told him to wait till she had a chance to go through things, so Charlie drove over each evening to see the progress she'd made. Knew if he didn't, she'd drag it out till eternity.

On one of those nights, in the biggest bedroom, the one where he'd slept as a child on a floor pallet between his two uncles in their tall iron framed beds, she showed him a trunk he'd never seen open which contained his father's belongings; she had idolized the man for near to fifty years, hoping that if she could somehow rewrite the history of her life, the shame and guilt of her family and her church and herself would somehow be erased. But the truth of it was there all the same.

Charlie told me on that day he was glad that his daddy had been killed. Glad he'd not known him. Said he could make up his own idea of what a father should be and live that with his own kids. I told him that was a right smart way to think, because I'd known his father before I headed out west, had run across him in the tavern or the pool hall, and while I didn't think bad of him, for God knows I ain't never been no saint, I know he'd have never been there for Charlie. So I told him the best thing I could without lying straight through my teeth. I said, your dad was a prince of a man when he wasn't drinking. And I left it at that.

But no matter how much Charlie had tried to forget what his father had been, his mama had kept a shrine to this man inside a wooden trunk, and now Charlie had to face the physical reminders of the dead man that was his father, instead of the one he'd made up in his head. Inside the trunk was a pair of wool dress pants, a watch, Wibb McMaster's birth certificate, and a half pack of Camel cigarettes that'd been in his shirt pocket the day he'd been killed.

I asked him what his mama had done with the stuff.

He said, she took it all in the trailer, and I haven't seen it since.

I said half joking, she ought to smoke one of them old cigarettes.

And he said yeah, fire it up and say, my life was shit and here's to it.

We sat for a second, then I said, I wonder what a fifty-year-old cigarette would taste like.

You know, Charlie said, his face as serious as a heart attack, that gets me to thinking.

After working all morning trying to bring down the house, with chains run from the backhoe and hooked through the load bearing walls, we only succeeded in pulling off the front porch, which was a bit of a disappointment, since it looked like it would've fallen over on its own come a slight breeze. After that, Charlie got fed up and extended the hoe full length, started swinging it like a giant club into the main chimney till it crashed through the roof. Over and over he swung that arm, hydraulics hissing, the slap of iron against wood and masonry, till the house lay in ruins.

I don't know. Maybe I'm wrong. But while he was doing this, I want to believe every stroke of that machine, every fallen brick and cracked rafter, drained away some of his life's bitterness.

But now, as I think on it, I don't remember hope on his face. Only disgust. Guess it was then he knew that every plan he'd ever make was futile. That's what he told me later. Said, how am I ever gonna change this farm when I can't even make a dent in the cat population. Can't even get rid of a trunk full of motheaten memories.

It's when he realized this place would never be anything more than what it was. A pig farm turned junkyard. His boyhood home.

_____

Charlie kept his word and worked on the farm all the rest of that year: had an auction, which barely made enough to cover expenses; burned the old wooden barn at the back of the lot with all its contents still inside, hoping it'd save time, only to end up with a giant pile of cinder blacked wood on top of melted plastic and rusted metal; hired his son-in-law to help him, only to see him nearly killed when the tractor he was using to pull stumps turned over on him. One calamity after another.

The final wound salting came when he found a musty account ledger tucked away on a shelf in the machine shed. His uncles had used it to keep a running inventory of all the things they bought and sold. It began May 5th 1947, and the last date they'd entered was July 19th 1979. After that, they sold so little compared to what they bought, they just kept a tally in their heads.