Rusty Barnes's Blog: Fried Chicken and Coffee, page 30

May 11, 2012

God Didn't Get Me More Weed, by Mather Schneider

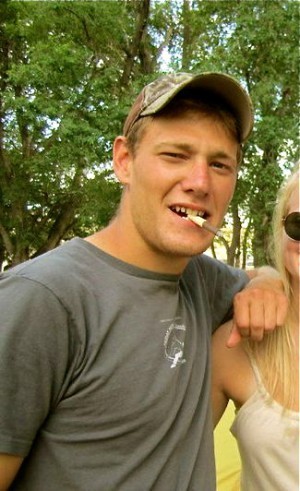

Me and Little John were sitting at the bus station behind the wheels of our taxi cabs. We were far, far down on the cab cue, so we wouldn't get a fare for a while. It was a depressing place to be, number 9 or 10 on the bus station cab cue. It was about 4 in the afternoon.

Little John was on his cell phone. His 7 teeth flashed in the sun.“Hey, Donny,” he said into the phone. “What’s up? Where you been?”

He looked at me through our open windows and gave me the thumbs up.

“What?” he said. “No, no, man…Hey, is Jay there?… Where is he?…Don’t fuck around man, I’m completely out, I mean

I had a couple of buds stashed away for an emergency but those are gone now and…What?…No, hey, you know me, man, I can’t live like this. I AM A MAN WHO NEEDS HIS WEED! Ray? Ray? Hello?”

Little John looked at me again. “Fucker hung up,” he said. “He’s blowing me off, man. But I’ll get to him if I have to drive this fucking taxi all the way to fucking Yuma.”

Little John was 5’6” and weighed 245 pounds. He had bad arches that caused him to walk with a stiff-legged lurch, but he hardly ever walked, he mostly remained behind the wheel of his cab. He was most comfortable there, and had the appearance of being a physical part of the vehicle. He was 47 years old with over-washed salt and pepper hair that fell down his neck and onto his Neolithic forehead. A wart poked its nipple-like head out of his right cheek and he had the habit of rubbing it while he talked.

"Don’t smoke pot before you come to work,” the boss told Little John one time.

“Be reasonable,” Little John said.

“Well, don’t smoke at least 3 hours before work.”

“One hour.”

“Two and a half.”

They settled on two hours but Little John smokes throughout his whole shift anyway. He goes home and smokes a joint and then he’s back in his taxi, or he just smokes in his taxi.

But today he ran out of weed for the first time in years.

"I can't live like this," he said. "I've got to work, I've got to drive this fucking taxi, I've got to make money. I've got to deal with these people, all these mother fuckers…"

"Easy," I said. “God is listening."

"Fuck god," Little John said. "God didn't get me no weed."

"You hear me, mother fucker?" he said, leaning his head out his cab window and looking at the sky. "Fuck YOU!"

He brought his head back inside the cab and looked straight ahead with a sigh. He sat there for a second. Then he gave me a worried look, and put his head back out the window.

"Just kidding," he said to the sky.

Just then a black van pulled into the bus station parking lot. The hot sun reflected off the shiny black paint. The van stopped and a muscular tattooed white guy got out the back. Then the driver got out, a fat white guy in a white shirt. He ran around the van and grabbed the first guy and started beating him in the face with his fist. He hit him about ten times, rapidly, and the guy crumpled onto the ground. Then the guy got back in the van and drove off.

Little John jumped out of his cab and ran over to the guy on the ground. A couple of other cabbies wandered over too. Little John bent down and helped the guy up, and then the guy tried to hit him. Little John pushed him off and the guy stood up and stumbled away toward Broadway.

Little John walked back to his cab, defeated.

“Some people just don’t want help,” he said.

“Did you ask him if he had any weed?” I said.

“Don’t joke about it,” he said.

“Something will come up.”

“Easy for you to say,” he said. “You’re a drunk. All you have to do is go to the store.”

“Except on Sundays,” I said. “On Sundays I have to wait until ten o’clock. We’re living in a police state.”

“Poor baby,” Little John said. “Poor god damned fucking baby.”

“Yeah, yeah.”

“Shit, I got to get out of this city. I got to get back to the country. I was raised in the country, you know.”

He lit a cigarette.

“We used to have chickens, goats, pigs, all that,” he continued. “That was the fucking life, better than this shitty city. This place is fucking dirty, man, and full of assholes. Plus, in the country you can grow your own weed.”

“So what’s stopping you?” I said.

“I don’t know, I’ve got my apartment. Besides, how would I get money?”

A Greyhound bus pulled into the station and emptied itself of people. A few of the cabs in the front of the cue got fares, and pulled away. Then the whole cue moved up and everyone got in their cars, moved 30 yards up, and parked them again.

“I had this one little chick,” Little John said, “on the farm. “Little fuzzy yellow thing, and she grew attached to me. I named her Peepers. Damn, she was cute, man, you should have seen her, she would follow me around everywhere I went.”

“How old were you?” I said.

“I was like 8 or 9 I think, yeah. Shit, Peepers, I haven’t thought about her in a long time. But it’s sad though, because one day we were running through a field, and I was running real fast, you know, and I guess she just couldn’t take it and she stopped. I felt bad and went back and bent over her and she was breathing real heavy and kind of twitching in the grass. Jesus, I started crying. And then you know what happened?”

“What?”

“Her heart exploded! It fucking exploded right out of her chest. Right out of her little fucking chest.”

I gave him a look.

“I’m serious, it did, exploded right out of her chest, there was blood on the ground, it was terrible.”

Little John seemed to go into another world and a tear fell down his cheek. He looked away and wiped it.

“Maybe you should just stay here in the city, big fella,” I said.

He shook his head up and down but he couldn’t talk anymore. The cab cue was dead.

“I’ve got to go,” I said. “I’ve got a personal.”

“Ain’t you lucky.”

I pulled out, to the delight of the cab driver behind me. Everything starts with moving, just keep moving and the luck would change. It was like death just sitting there.

I drove over to the Food City by Randolph Park and got a hot dog at an outdoor stand. A Mexican guy handed it to me and it was loaded: beans, ketchup, mustard, mayo, onions, tomatoes, cucumbers, cheese and bacon.

I was standing there eating the hot dog next to my cab in the bright sun when I saw a man running toward me across the Food City parking lot, waving his arm. He was lugging a suitcase and it was obvious he needed a cab. Come to papa, I thought. He was running like his heart would burst from his chest.

I was born in Peoria, Illinois in 1970 and have lived in Tucson, Arizona for the past 14 years. I love it here, love the desert, love the Mexican culture (most of it), and I love the heat. I have one full-length book of poetry out called DROUGHT RESISTANT STRAIN by Interior Noise Press and another called HE TOOK A CAB from New York Quarterly Press. I have had over 500 poems and stories published since 1993 and I am currently working on a book of prose.

I was born in Peoria, Illinois in 1970 and have lived in Tucson, Arizona for the past 14 years. I love it here, love the desert, love the Mexican culture (most of it), and I love the heat. I have one full-length book of poetry out called DROUGHT RESISTANT STRAIN by Interior Noise Press and another called HE TOOK A CAB from New York Quarterly Press. I have had over 500 poems and stories published since 1993 and I am currently working on a book of prose.

http://www.nyqbooks.org/author/mather...

May 8, 2012

Hill Tide, fiction by William Trent Pancoast

As Violet jostled among the church crowd and exchanged greetings, she tried to recall the sound of the spring that spurted year round from the base of the hill behind the cabin. But the voices and heat prevented her from hearing anything but a humming noise, as if everything around her were vibrating. She was at the door shaking the minister’s hand.

“Glad to see you, Mrs. Taylor. You’re looking well.”

“Thank you,” she answered, and wondered, as she was enveloped by the sweltering heat outside, how she had come to be where she was at this very moment.

She walked slowly. A group of children played in a lot behind the Gulf station on the corner. Decisions had shaped her path, caused her to be out this afternoon on a busy street in South Charleston that went for miles past warehouses and factories, and led finally into the hills, where she knew the smoky haze of the valley would be left behind. But everyone made decisions.

She continued on her way, deep in thought. She was a thinker; the years of isolation in her big house had, if nothing else, caused her to spend many hours and days thinking. But more often than not she felt as if she were in a maze, and that thinking only led her deeper into it. So it was now as she thought of her life. And what her mind told her, what it showed her about her life, was not much: only that every thought she had ever had and that every decision she had ever made placed her, at this very moment, on this dingy street in the midst of the stinking chemical factories of Charleston, West Virginia.

Then she was at the door of the big, white house. It was too large for her to take care of anymore. Once it had served a purpose, providing the room for her several children, who were now pursuing their own lives. One of them, the oldest, had become a doctor; another was an engineer. But they had all but forgotten her. The letters came seldom if ever, and the visits had stopped long ago.

As she opened the heavy, wooden door and entered the old house, her thoughts were of the farm and the joy she had felt as a child growing up there. She ate, and after sitting for an hour or so, mentally exploring what she could remember of her childhood, called her sister.

“Hello, Myrna. How are you?”

“Oh, I’m fine. But it’s so hot.”

“I was thinking…I’m going for a ride to cool off. Would you like to come?”

“What a grand idea.”

“Okay, I’ll pick you up.”

She grew excited as she drove to Myrna’s. At least, she thought, she was breaking the monotony of her routine, that sameness that made up her days. As she wheeled the old Chrysler through the familiar streets she suddenly pictured her wiry, mustached father riding the plow along behind the horses.

Myrna was waiting on the porch. When she was in the car she suggested, “Let’s drive up to Cane Creek and see the Johnson’s.”

“No,” Violet answered quickly, “Let’s go down to the river.”

“What river? The Coal or Kanawha?”

“No. Our river.”

Myrna looked confused. “You mean down to the farm?” she exclaimed.

“Yes. That’s our river. Wouldn’t you love to see it again?”

“I don’t think so…you know what Daddy said before he died. He said never go near there. It’s all grown up and there never was a road built past the farm.”

Myrna was silent as they started the ascent into the hills. At one curve a goat sat on a rock ledge overlooking the road. She was glad they were in the country and, besides, she knew she couldn’t change Violet’s mind once it was made up. “Okay,” she finally said. “I’ll go, but only because…because I want you to see how foolish you are, always talking about that desolate, old farm.”

Violet liked to see the cabins along the creeks, the saw mills, and the people. She even liked the dingy, skeleton-like remains of the coal mines – at least they reminded her of things she had known when she was young. The city had no memories to give her, she thought, envying the people who sat on their porches in the shade of huge trees and who had mountains for back yards.

All afternoon they drove through small towns, coming closer to the farm their father had homesteaded after the Civil War. In the distance, Violet saw a string of engines laboring their way out of the hills with a line of coal cars trailing behind and a memory flashed: She and Myrna and Perry had just come down the wagon trail on their way to school. They had to wait for the train to go past on its way to the next siding, which was near the school. Perry ran alongside one of the cars, and jumped for the ladder, intending to ride to school. But he slipped as his foot hit the frost-covered rung. After he had recovered from the near fall, laughter took the place of his fright, and clowning, Perry hung from the ladder with one hand to show his sisters he wasn’t at all scared. Then came the jolt. Perry fell and the car skidded along the slick rails, severing his legs. He writhed on the gravel for a few moments before he lost consciousness, and when Violet reached him, his blood-spurting stumps were covered with cinders. “Get Mamma!” she cried to Myrna who stood in tears where she had been when Perry fell.

“Look out!” Myrna cried as the car veered into the other lane on a curve. Violet jerked the wheel to the right and barely missed a car. When they were on a straight stretch of road, Myrna said, “Let’s turn back.”

“Turn back! Why, we’re almost there.” She had to see the farm now, if only for a moment. She had to see the spot where Perry had died in her arms. She had to see things as they had been.

Violet drove several miles south along the Tug River until they came to the bridge to Kentucky. There she stopped at a combination gas station and church. “Hello,” she said to the man who came out. “Can you tell me the best way to Larson Creek?”

He looked to his feet and stirred the gravel with first one foot and then the other. Brushing his matted hair back, he squinted into the car. “What business y’all got there?”

“We used to live there. How long have you lived here?”

“Not long.”

“Oh,” she said, and since he had nothing of the past to share with her, asked again about the way.

“You kin go a mile or so down the Kentucky side,” he said pointing to the bridge, “and walk the river on the foot bridge. Or you kin go behind the place here and take the railroad utility road.”

She thanked him, and they started along the cinder road along the railroad. Shacks lined the bank. Many of the buildings were deserted. In the inhabited ones, families sat on the lopsided porches watching Violet’s Chrysler intently. Barefoot children ran along behind in the dust until they were shouted back. Violet stopped at a shack that had a “Barber Shop” sign on it. Two men sat on the porch drinking beer. She got out of the car to ask directions and the men walked out to her. She looked closely at the taller of the two. “What’s your name?” she blurted.

“…Oapie.”

“Oapie…Oapie Watson!” she said upon associating the name with the man. He looked surprised.

“I’m Violet Taylor…Don’t you remember me?”

He stretched his neck forward. “It’s been a long while, ain’t it?”

“It’s been so long I don’t even recognize much here,” she said looking around. “We’re looking for Larson Creek. As I remember, it should be right around here.”

“About fifty yards further. You can’t see it. It’s all growed over.” He pointed down the tracks. “Right where that big tree limb sticks out of the growth. That’s where Larson Creek goes under the railroad.” The other man went back to the porch where he carefully placed his empty bottle in the top beer case.

“Does anybody still live up the creek where our place was?”

“No, ain’t nobody been up there for years.”

“Well, we’re going up and look around,” Violet said, and turned to Myrna, who sat looking straight ahead. “You remember Oapie here, don’t you? Imagine, after all these years, Oapie’s still here!” Myrna sat still, her lips drawn tight.

Oapie stepped forward as Violet turned to get in the car. “You don’t want to go up there. Snakes all over the place.”

“I used to live there. You can’t scare me with your snake stories.”

“Ain’t wanting to scare you. But the stripmine does it – they stir up the snakes and they come down here. I kilt one right here under the porch t’other day.”

“Well, I’ll take my chances,” she said, getting into the car. “Thank you, Oapie,” she called as she drove away.

“Let’s leave, Violet,” Myrna said. “I’m scared of these people. They aren’t our kind anymore.”

“Nonsense.”

Myrna looked back. The other man had joined Oapie at the road where they stood staring after the car. “What are they staring at, then?”

Violet parked the car in front of an abandoned shack and grabbed her cane off the back seat. “Are you coming?” she asked as she got out of the car.

“No, I don’t want to see it.”

She picked her way up the railroad bed, crossed the tracks, and stood looking down the eroded bank of the creek. The water was muddy with traces of orange running through it. Trees grew on the wagon road her father had cleared. She looked ahead to the hill, before which would stand the cabin. At the top were great bare spots, and scattered down the hillside were huge rocks and piles of debris. Briar patches, stunted trees, and weeds covered the fields her father had farmed. After a couple more minutes she could see the chimney, which she found was the only part of the cabin still standing.

She heard a train whistle in the distance and stopped. The river was visible below. A junked car protruded from a shallow spot. There was a graveyard on the far bank. A fire had destroyed the cabin. The barn still stood, but most of the siding had rotted away. She had expected to find things much as she had left them, but saw now that time had done its work.

Then she saw the spring and started towards it to get a drink. She stepped over a charred log and felt something sharp tear at her leg. She thought it was a briar or a piece of barbed wire, but then she saw the copperhead. Drops of blood oozed out the tiny holes in her calf. She flung the snake away with the cane and went on to the spring. After a long drink she started back.

She wasn’t worried that she had been bitten; it wasn’t her first snake bite. But she felt dizzy after a few steps. She sat down on a large rock between the spring and the chimney. Feeling very tired, she lay down on the grass, aware of the spoilage and waste that lay all around. Yet she was glad to be here, and for the first time in many years, felt at peace. As she lost consciousness she was a girl of ten helping her father feed the animals late on a summer evening, and the cool breeze that had picked up at the coming of dusk was welcome after the heat of the day.

Myrna had started to follow Violet, but turned back before she had gone far. The train had come suddenly and she had stood at the bottom of the wagon road waiting for it to pass. As the heavy carriages rumbled past, she heard Violet screaming. What? “Get Mamma!”

Shaken, Myrna made her way back to the car. She watched for Violet to return along the creek bank until it was too dark to see anything. As night sounds and evening mist surrounded the car, Myrna began crying softly. She felt the cool air blowing down from the hills and smelled wood smoke, and wondered how she had come to be where she was at this very moment.

Hill Tide was first published in 1976 in The Mountain Call out of Kermit, West Virginia, and again in Apple Magazine of Mansfield, Ohio, in 1978.

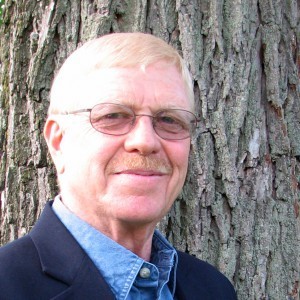

William Trent Pancoast's novels include WILDCAT (2010) and CRASHING (1983). His short stories, essays, and editorials have appeared in Night Train, Solidarity magazine, and US News & World Report.

William Trent Pancoast's novels include WILDCAT (2010) and CRASHING (1983). His short stories, essays, and editorials have appeared in Night Train, Solidarity magazine, and US News & World Report.

May 5, 2012

What He Asked, and How She Answered, fiction by Brian Carr

At the window, with it open, as rain sang across the land once dry, so the rain slipped in threads of current down cracks and toward the lows, the man wiped his glasses free of spray—beads that had hit the sill and splattered at him. He cleared his throat, put the glasses back on, picked up a cigarette weaving smoke into the pale-yellow room—a light cast by a single bulb dangling above the kitchen table from a cord, makeshift.

“Would you say,” said the man now ashing his cigarette, smoke staining his words, his eyes toward the rain, “that I am very brave?” He then looked at a woman, wrapped in a blanket, her eyes tight against the chill, her body frail with age and labor, her hair winced gray by days. She tightened the blanket across her shoulders, leaned against a wall—faded white paint, cracked and spotting.

“These days?” she said, and looked now at the rain, sighed as if she knew it only came to wash her off the land, to hoist their home from its foundation in a torrent toward the death of it—nature ravaging its boards and bones to splinters and shingles and scraps and refuse that would toss wildly in the breath of flood until it came to rest unrecognizable. She closed her eyes. Turned from the man. “I wouldn’t even call you handsome.”

These days the couple bickered, made fights from moments others might let pass silently, but in the past they would hold hands until the warmth of their palms birthed a slickness from sweat, but even then their fingers stayed clasped through the damp. They’d speak cute phrases to each other—the man warmly cooing her name, the woman smiling when she heard him coo it. But that music had faded from them.

The man looked at the woman, nodded, said, “I’m ugly,” he said, “but ugly men can live bravely.”

“They can,” said the woman, and she stayed silent a moment so only the sound of rain filled the room, and she looked at the man, lazily blinked her eyes, smiled so slightly only she could sense it. “But I’ve never seen it.”

The man shrugged. He ashed his cigarette mildly. He turned back toward the rain. They didn’t speak for a long time.

Brian Allen Carr's debut collection Short Bus is out with Texas Review Press, and his next book, Vampire Conditions, is out soon with Holler Presents, and it will play card tricks for you and hide your keys. He teaches at University of Houston-Victoria, and he wants you to visit.

Brian Allen Carr's debut collection Short Bus is out with Texas Review Press, and his next book, Vampire Conditions, is out soon with Holler Presents, and it will play card tricks for you and hide your keys. He teaches at University of Houston-Victoria, and he wants you to visit.

May 2, 2012

poetry by G.M. Palmer

September

The night sweats through the humidity,

our humanity exhausted on the porch

collapses from the draw of breath

through the thick Autumn air.

Steam and mosquitoes, blood and bile

are mingling with the mist

of burning crosses, churches, forests

as our spirits are paved under

by carpetbagging revenuers

who worship at the font of progress

while drowning our children in the water

meant for the improvement of man.

The morning breaks at eighty degrees

as the sun strains through ancient oaks.

Pavement gravestones

mark the memories of generations

blanketed in tar and steel and concrete

over the coquina sands of our ancestors

fed by the silent Aucilla and cacophonous swamps.

Old men cypresses are slaughtered for clocks,

their knees cut out from under them, choking

as their blood is leeched for another suburb

where timed rain beats the four o’ clock downpour,

and waters the evergrowing asphalt.

The day beats in volcanic reality,

smothering all intention and thought.

The freoned tinted castles lord on,

the strapped Earth begging for a hurricane

more crafty than the newest building codes,

they continue in their oblivion

as the alligator stalks the cul-de-sac for another poodle,

and another child swims for the final time

as the marcite reflects the sun onto his face,

waiting for mommy to return, arms full of bags

to wonder where the housekeeper has gone

as her favorite soaps blast into the windows.

The evening drifts up from the glazed streets

after cars disappear into cement caves.

Bare feet step out into drying sand

to pick ripe tomatoes for dinner.

The sun sinks behind Spanish moss

and a last ray dances through Depression glass

to kiss the simple ring that reaches over the stove

to the spices that will kiss the wrinkled recipe

that has defied the swell of the growing years

and retains the taste of sinking into the freshest dreams.

Every native who has loved the soil and the salt

prays for peace with each day’s passing.

Rawhide

Stray dogs are ripping widowed paper bags.

Nearby lies a broken heel; a leg out of place;

a skirt, hem slung around; a mouth that sags:

a hole in a yellow, faded, made-up face.

A mongrel tears a strip of rawhide free

from a faded bag. His teeth sink in the soft skin

as bitter drops fall from the balcony

where a girl is wringing out her clothes again.

His ears twitch, hit with the brown sinkwater

that pours from dirty panties. He turns his tongue

to lap the steady stream. The girl drops her

wet rags, coughing. He gnaws at the blood and dung.

The mongrel drops his skin in the filthy light.

Her love is coming home to stay tonight.

G.M. Palmer preaches, teaches, and wrangles children on an urban farm in Northeast Florida. His criticism and poetry can be found throughout various blogs and magazines, both in print and online. His children can be found throughout the neighborhood or at their

grandmother's house. His notes can be found on legal pads and spiral notebooks. His business cards can be found with neat little poems on the back of them.

April 29, 2012

Moon in the Holler, poetry by Gina Williams

a psycho killer. Biggest in a hundred years. Old preacher says it’s a sign, predicts

earthquakes and insanity, says God and the moon are in cahoots to make us pay. Why

stop there? Let’s blame it for every little thing. Like fat kids, mean people, rheumatism,

annoying relatives, bad breath, broken pipes, toe jam, moldy bread. Mean, annoying

relatives with gum disease, rheumatism, bad breath, fat kids, broken pipes and toe jam

who serve moldy bread. Made me do it, made me kill my whole family, toppled the

house of cards, burst the artery that flooded the basement that gave me a wart that killed

the pig that gave me worms that stunted my growth. It’s not just for werewolves

anymore, so go ahead and get a slice of moon pie for yourself, while you have the

chance. Everybody’s doing it and it tastes like chicken. Gun the engine, skidding on the

gravel road, skeleton branches scraping the hood, deep into the thick pine woods where

the moon don’t shine, won’t follow, can’t be blamed for anything.

Gina Williams lives and writes in the Pacific Northwest. She enjoys poetry, fiction and photography. She is a perpetual student, working towards a degree in Rough Arts from Life University. Writing, she has found, makes it possible for her to breathe.

April 26, 2012

Retrieve, poetry by Michelle Askin

How did you ever think you would justify anything as good,

after abandoning her for sweet prayer in a stone fruit orchard

or wonderful deed saints you held in the knowing? How about

your holy hand to try art: cupping chopped off chicken heads

from a prison’s construction site gravel. You paste them by 7Up

and propane bottles for picture, for meaning. What sacrifices

could ever be more meaningful than that night at Hearty Stop In Grocery?

Tell me now why you left the house made of wire for an insane woman,

who rushed you to that store for distilled water to pour in her breathing box

so she might sleep. Always when awake, the black wallpaper was a stove

where her rapist step father scalded her baby sister to death.

She thought you were the father and sought to murder you as the father.

Thought you were the hooker mother, who saw this happen the way

one sees a movie happen: up close but the story is far away.

She sought to murder you as the mother too.

The clerk would sell you winter squash and rifles for clearance.

But you kept saying water and no, no distilled. And she just laughed

in her wart-wide mouth. Just said, Well Kroger has that.

The only Kroger around here is closed. You tried to run,

as nothing was funny. As the clerk shot dead silver wing butterflies.

And the room became traffic crash debris with fast rain falling over.

My poetry has appeared in The Northern Virginia Review, MayDay Magazine, 2River View, Oyez Review, The Sierra Nevada Review, and elsewhere.

April 23, 2012

Four Day Worry Blues, fiction by Murray Dunlap

Round 1:

I’m naked to the waist. The first blow comes in low and fast. I weave left, but his fist catches my right oblique. I spit blood onto bare feet and uppercut with my right. I miss. His jab catches my chin. The room blurs and I step back. The cross lands hard against my temple. I feel the wall at my back. I feel glass breaking against expensive art. I feel the floor rise up to my knees. Leaning forward, my sweaty fingers grab at the edge of the rug. The woolen threads feel soft. My face presses against hardwood and glass. I smell bourbon. The man buttons down his cuffs and leaves the room. It’s our first living room, the one before all the divorces and the step-this and half-that. I have this dream every night. Sometimes the man is my father, sometimes it’s Mason. Most times I can’t see his face. Either way, we go at it bare knuckles. This morning, I wake up with bruised hands.

Round 2:

I duck down, stepping back and blocking with my fists. He comes in fast. He lands two jabs, an uppercut, and finishes with a cross. I’m blinded by sweat and blood. I cover my face, peering between fingers. It’s Dad tonight. No, now it’s Mason. The dream is always like this. I shut my eyes.

Mason lets me stay in his room the first night at the University. Dad forgot to send boarding fees. No one knows where he is. The guy assigned to live with Mason never shows up, so things work out. Mason and I have been best friends since middle school. His hair turned gray senior year, so I started calling him Governor. Then everyone did. It was as much for the hair as for his politics. He wants to be JFK. He keeps our room white-glove clean. Mason’s father, who drove up for welcome weekend, gives Mason an Oxford English Dictionary. He wraps thick, hairy arms around our necks and says Sewanee will make men of us. I hear him remind Mason that his scholarship requires at least a 3.0. Mason reminds his father that he was valedictorian. The father gives Mason twenty dollars. Through the crack of the bathroom door, I watch them hug.

The dorm is coed. I walk the breezeway overlooking the courtyard. Heather steps out of her room in flip-flops with a towel over her shoulder.

“Have you taken the swimming test?” she asks.

Heather braids her ponytail and looks at me with huge green eyes. A black bathing suit shows through her t-shirt.

“A test?”

“The University says every student has to swim 50 yards.” She spins goggles on a finger. “They don’t want us to get drunk and drown in one of the lakes.”

“Oh,” I say. “I didn’t know.”

“The lakes are everywhere. Little death traps when they freeze under the snow.”

“I swim all right.”

“I’m going now. Wanna come?” Heather taps painted toes. She smiles.

“Sure. I think so. Is the test in a lake?”

“Of course not. The cold would kill you.”

“But it’s only September.”

“Are you coming or not?”

Round 3:

I try a jab-cross combo but the man is quick. The cross leaves me open and the man drives a straight to my ribs. I hear the stitching rip in his starched white shirt. I pull up, lift my fists. He uppercuts to my jaw. Blood fills my mouth. I can’t catch my breath and I can’t see clearly. The man turns blurry and his next hit lands across the bridge of my nose. I step back. I hold out my hands in surrender.

I’m packing for Montana. Dad said no, but I’m going. Heather’s going too. My canvas bag looks like a split potato with clothes popping from the seam. I slide my fly rod into an aluminum tube and fill a plastic box with Pheasant Tails, Zug Bugs, and Hoppers. Mason comes in from a mid-term and sits on his bed. A poster of JFK is taped to the wall over his shoulder. Next to it, his autographed photo of George Stephanopoulos. Our beds lie four feet apart in this tiny dorm room. He rubs a hand under his jaw line.

“My throat is killing me.”

“You probably pulled something studying last night. You should fix it up with a fifth of whiskey and dirty sex.”

“Seriously, it hurts.”

“All that reading will do you in.”

“Grades equal money.”

“How long has it hurt?”

“A week now. Are you going to hang that shirt up?”

“Does my nose look ok? Took a soccer ball in the face.”

“I can’t see anything.”

“You should talk to the nurse about that throat.”

“I’ll see my doctor at home.” Mason picks at the hem of his khakis.

“What about the beach?”

“Cancelled.”

“What?” I turn from my clothes and face him.

“I feel like shit.”

“Shake it off. Be a man.”

“Bite me.”

Mason picks up my shirt and hangs it in the closet. He opens our mini-fridge and grabs a coke.

“Whiskey, Governor. Not coke. And I’m packing that shirt.”

“I thought Montana was off?”

“Why don’t you ever drink?”

“What about your Dad?”

“Who gives a damn. It’s not like he’ll remember in a week.”

I turn back around, put my knee into the clothes, and press down hard enough to zip the bag. My ribs throb with pain.

Round 4:

Heather stands between us. She lifts both arms, palms out. She pushes off my chest. I move back. But the man grabs her hand and twists Heather to the ground. I watch his boot twist into her shirt as he comes after me. I put everything into a straight and knock Dad’s teeth out. But he gets up. He sits in a Windsor chair and gums a bloody cigarette. Heather disappears from the dream. It happens sometimes.

Dad says, “Got me good, did ya? But you’ll never get away. Look at that hand.” I look down at one of Dad’s eye teeth jutting from my knuckle. I pick it out and toss it to him. In the dream, he pops it back in his mouth.

On the east bank of the Blackfoot river, Heather and I sit on a fallen hemlock. We’ve fished through the cold morning. Warm sunlight finally breaks over the tree line as I light two cigarettes. I pass one to Heather. She moves to the water’s edge and balances at the edge of a flat rock. She flips up the creel lid and looks inside. Two browns and a brook trout slosh in the frigid water.

“Should we release them?” she asks.

“I thought they were dinner.”

“We bought steaks.”

“Fine by me.”

Heather lifts trout one at a time. She cradles their slick bellies underwater until instinct reminds them to swim.

“We should get a dog,” I say.

“What kind?”

“The big kind.”

“Like a Boxer?”

“No.” I rub my thumb against my index and middle finger. “Pound dogs are free.”

“You worry so much about money.”

“That’s because I don’t have any.”

“You’re rich.”

“Dad is rich.”

“What would we name it?” Heather throws the empty creel onto the bank and finishes her cigarette. She grinds the butt against a rock and thumps it at me.

“Blue,” I say.

“Why Blue?”

“Why does he have to be such an asshole?”

“Booze.” Heather pulls a six pack from the river. She hands me one.

“Blue is a good name for a dog.” I drink from my beer. “So when are you going to ask me about the fighting?”

“What fighting?”

Patches of sunlight flit across my hands and the cuts are harder to see.

“Yeah,” I say. “Blue.”

Round 5:

The man lands his first punch. I shake it off, skip right, and work a combination. My jab nicks his chin. He side-steps the cross. Then he lands three for three and I’m spitting blood. I try to call the fight, but my swollen tongue won’t produce sound. I duck under the harvest table and stay to the shadows. Broken glass litters the cold floor. It smells like bourbon.

Mason’s not at the dorm when I get back, but the room is immaculate. I unzip my bag and throw every single piece of clothing on the floor. I check the machine. Two messages from Mom and then it’s Mason: Hey Ben. I’m still at home. I’m sure I’ll be back in a day or two. How was fishing? Call me.

I pick up the phone and dial.

“Governor.”

“Ben.”

“Got your message.”

“Yeah. It’s not good.”

“What’d they say?”

“They did a biopsy on the lymph node in my neck. Hurt like god-almighty.”

“Shit.”

“It’s Cancer.”

I say nothing. I scratch at the back of my head and look around the room. Fishing gear on the bed, skis in the corner, and my bike hangs from the ceiling. Mason hardly owns a thing.

“Hodgkin’s Disease. That’s what they called it. Said it’s treatable. No sweat.”

I tap the phone against my ear.

“You still there?”

“Yeah. I’m here.” I struggle for words. “Sorry, Gov.”

“It’s fine. I’m fine.”

“I’ll come down there. It’s only a couple of hours.”

“Seriously, I’m fine. How was fishing?”

I tap the phone against my ear.

Round 6:

I move in and uppercut to his stomach with my right. The man staggers back, bumping into the silver tea service and toppling the sugar bowl. He spits to the hardwoods. I see blood. He’s angry now, but I still can’t see his face. This time he throws a haymaker. I’m off my feet and falling fast.

Dad leaves the cabaret. The highway is dark. He steers with his left hand and drinks ’82 Lafite Rothschild from the bottle with his right. “Hothouse,” he says. “Hell of a place.” The wet blacktop glitters under stray pockets of lamplight. Dad finds the replay of the game on the radio. The Cubs are up by one at the top of the ninth. He listens to the Reds strike out as the right tires of the Mercedes stutter on center markers. The car drifts into the right lane. He taps his thumb against the steering wheel and closes his eyes. The shoulder gravel vibrates the car and Dad wakes. He overcorrects left. The car crosses both lanes and dips into the grass median, popping over the muddy ditch and climbing the other side. Dad looks into the glare of oncoming traffic as his car leaves the median. All four tires leave the ground. The Mercedes’ front bumper hits first, shattering glass and bending metal on the rear door of a tan Buick. Both cars spin off the shoulder and into the weeds.

A highway patrolman is first on the scene. He calls in the ambulance and checks the Mercedes with a flashlight. Blood runs from Dad’s forehead into his open mouth. He taps the steering wheel with his thumb.

“Hey hey, Cubbies,” Dad says.

“Sir, are you all right?”

“Chicago wins again.”

“Do you know where you are, sir?”

“I’m in Alafuckingbama you little shit.”

“I see you’ve been drinking.”

“The ’82 is every bit as good as the ’59.”

“Don’t move Sir, paramedics will be here soon. I need to check on the other car.”

The patrolman jogs to the Buick. He checks with a flashlight. The woman in the driver’s seat slumps forward. The child in the back screams. The patrolman feels for a pulse on the woman, then turns to wave the ambulance in.

At least, this is how I imagine it happened. I’ve talked to the cop. I feel sure I have it right.

Round 7:

I come at him swinging. I’m hyped up and punching hard. The man dances around my swings, grinning. He bobs side to side, then lands a cross to my jaw. The sting of it flicks a switch in my head and I rush him. I shove him to the ground and kick his ribs. The man curls into a ball. I kick his face and sides, the back of his head. I jump down and grip his shoulders. I spit in his face. The man keeps grinning as Heather pulls me off. Even this close, I have no idea who he is.

Mason lies back in the ICU, head elevated by pillows. A ventilator breathes for him. Vaseline has been slathered in his eyes. I’ve been told it’s a lose-lose situation. They can’t treat the Hodgkin’s for a virus in his heart and they can’t treat the virus for the Hodgkin’s. The waiting room is crowded with family and friends, but the doctor only allows us to say our goodbyes one at a time. Mason’s sisters and mother talk us through it. The older sister says, “He can hear you, so say whatever you want.” I don’t know what to say. On the nightstand, the mother tears open a white sugar pack for coffee. Her hands tremble and less than half finds the cup. She tears into another. The younger sister looks up to me, then turns to Mason. She says, “Time to go play in the clouds, Bubba-cat.” At this, the mother cries. I start to ask why she calls him Bubba-cat, but don’t. I realize it’s time. Mason’s mother hugs me, but cannot speak. I stare over her shoulder at the spilled sugar. Mason’s mother kisses my cheek. I move to the table and brush the granules into my hand. I make sure I get them all. Then I nod to Mason and step out through the curtain so the doctors can turn off the machines.

Round 8:

I land two jabs and a cross. The man takes one step back, then drives forward with a straight to my nose. I fall backward onto the antique butler’s tray. Bottles of wine shatter under my weight. I look up from the floor and see the man picking through the shards. It’s Dad. He lifts a piece with the label still intact and reads from it. “Intensely flavored with cassis, spice, and wood.” He drops the glass and stands. He crosses his arms. Heather steps in from the kitchen and rushes over. She kneels in the wine and presses two fingers against my wrist. She’s saying something, maybe even yelling, but I can only see her lips move and chin tremble. I can’t hear a thing.

Dad gropes the sheets with shaking hands. He kneads folds of thin fabric, releases, then kneads again. Blood soaks through a bandage on his forehead where the ’82 Rothschild pierced his skull. I’m the only one here. I sit on a metal folding chair and look at the dull monitor screen, blipping without rhythm. I glance at my hands, three band aids on the left, four on the right, then down to my leather boots. I bought the boots years ago. Just like Dad’s. Same brand, same size. A scuff on the right toe matches one on the left heel where I kick them off. I dig the right toe in between the leather and sole, sending the left boot to the floor. Left boot, then right. Always in that order. Dad does the same. The monitor squawks and I look up.

“Horrible wreck,” the doctor says. “He may not make it through the night.”

I look at the doctor, expressionless, then back at my father. The tubes mumble and pulse. I can’t think of anything to say, and instead, I begin to hum softly. My voice grows stronger as the humming becomes words. It’s an old blues ballad by Blind Lemon Jefferson:

Just one kind favor

I’ll ask of you

I sing loose and smooth, imitating Blind Lemon as best I can. The nurses peer at me with sidelong glances. They pretend not to notice.

One kind favor

I’ll ask of you

I keep singing. I forget myself and sing loudly, loud enough that I think Dad might hear.

Lord, it’s one kind favor

I’ll ask of you

The monitor emits a constant beep that I remember from movies and dreams. I produce the last line with air from deep within my lungs.

See

that my grave

is kept clean.

The doctor moves to Dad and checks his pulse.

“Sorry,” He says. The doctor clips the heart monitor back on to Dad’s finger. “False alarm.”

The machine resumes even beeps.

“Christ,” I say.

“These little clips are tricky.” The doctor makes a routine check of vitals, and turns to me smiling. But then his face changes. His eyes open wide.

“You’ve got a hell of a nose bleed.”

I look down at my shirt, my pants. Blood covers everything. I lift my head and hold my nose.

“Nurse,” he says. “Bring me some gauze, a towel.”

I stare at the ceiling.

“Don’t worry son, your father’s turned the corner. He’s a real fighter.”

“Christ,” I say.

I ball my hand into a fist.

Round 9:

Mason goes down in a single punch, but I’m not sure I threw it. He falls back, opens his eyes and says, “Look at Bubba-cat now, he sure ain’t the Governor.” He won’t get up. I scream at him to get to his feet, but he lies sideways on the floor. He reaches for a blanket on the couch and pulls it over his face. Tables, chairs, paintings, and lamps lie in pieces around the room. There is nothing left unbroken. Heather stands behind me, so I turn to her. She opens a new pack of cigarettes and pulls two out. She lights them with a match. Music begins to play from somewhere unseen, distant and muted. But it’s enough. Heather drops the match into spilled bourbon as we walk through the door.

I say, “I’ve never left this room.”

Heather says, “You have now.”

***

I stand outside our crumble-stilts house, ten years since Mason died. Crickets edge between blades of grass, hidden, clicking and chirping the night song we all know. My toes yawn out, pressing into the cool and damp. Alabama moonshine falls across the lawn and my hands slip into cotton pajamas for a cigarette and match. Blue sniffs invisible trails, tail wagging and head down low. His muzzle turned gray last winter, and it’s hard to believe we’ve had him this long. Heather drove us straight from the funeral to the pound. We sat on folding chairs in a little square room and a woman brought puppies to us, one by one. Blue had the biggest paws. Today is his birthday.

We’ve just moved in to this house. We’ve unpacked our boxes and we’ve done the cleaning. We do not feel like strangers in this house. My grandfather built it. The Childress River winds along the back yard and disappears south. Dad jaundiced when his liver gave way to tumors last year. He survived the wreck, but not the drinking. He left all his money to a wife somewhere, but we don’t know her. Blue goes to the door and looks back to me. His shoulders sit almost as high as the doorknob. Above Blue, I see Heather through the screen. She no longer smokes. It’s harder for me.

The moon is closer to the Earth than usual. The night is clear and I look up at the craters, piecing together eyes and a mouth. I can’t make out much of a nose, and only when I squint does he take an appropriate shape. In this light, my hands appear ivory white. No cuts, no bruises. Leadbelly calls out to me from our window. It’s Four Day Worry Blues. I’m not sure if I’m awake, so I wiggle my toes. The grass feels real. Crickets drop layered chords into our song. I glance down at the silhouette of garbage at the curb, boxes and bags of Dad’s clothes and cracked glasses. With all his belongings inside, the house felt cluttered and dirty. So I threw them out.

Looking back to the moon, I say, “Goodnight Governor,” and take a deep breath. I put out my cigarette and walk barefoot to the house. Blue follows me in. Heather is already asleep, and I slip into bed without waking her. I watch her eyes dart side to side under closed lids. It’s warm here and I’m tired, so I make a fool’s wish. I put an arm around Heather. I shut my eyes. I wish to sleep without dreaming.

Murray Dunlap's work has appeared in about forty magazines and journals. His stories have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize three times, as well as to Best New American Voices once, and his first book, "Alabama," was a finalist for the Maurice Prize in Fiction. He has a new book, a collection of short stories called "Bastard Blue," that was published by Press 53 on June 7th, 2011 (the three year anniversary of a car wreck that very nearly killed him…). The extraordinary individuals Pam Houston, Laura Dave, Michael Knight, and Fred Ashe taught him the art of writing.

Murray Dunlap's work has appeared in about forty magazines and journals. His stories have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize three times, as well as to Best New American Voices once, and his first book, "Alabama," was a finalist for the Maurice Prize in Fiction. He has a new book, a collection of short stories called "Bastard Blue," that was published by Press 53 on June 7th, 2011 (the three year anniversary of a car wreck that very nearly killed him…). The extraordinary individuals Pam Houston, Laura Dave, Michael Knight, and Fred Ashe taught him the art of writing.

April 20, 2012

light year ghazal by Dennis Mahagin

Oh, I can hear the crickets swarm, on warm starry nights harping

rhapsodies: it's as if their surf-like sighs might span even light years.

When fireflies … get the act together… right? Teaching rainbows,

jelly fish, meteors' moons and tides: how to fluoresce in light years.

A hypothalamic filament that crackled ( zzzzzzzzzzzt ) when cordite

split the banyan: ablaze from heights of light, a candle made of years.

I wonder if Sagan or Hawking knew how loneliness felt to a comet

in Orion's belt, humping its own tail; oroborus for a million light years.

Yes, all the rage, all the rage when men begin to gauge distance via

Time; as dotted lines on a freeway flit … in endless fits of white years.

In other words what angels say, sotto voce, tangled up with hopeless

recidivists: in one ear: LIGHT; the other might take many, many years.

Dennis Mahagin is a poet from eastern Washington state. His writing appears in Exquisite Corpse, 3 A.M., 42opus, Stirring, Absinthe Literary Review, Prime Number, Juked, Smokelong Quarterly, Night Train, Pank, Storyglossia, and The Nervous Breakdown. He's also an editor of fiction and poetry at Frigg Magazine.

Dennis Mahagin is a poet from eastern Washington state. His writing appears in Exquisite Corpse, 3 A.M., 42opus, Stirring, Absinthe Literary Review, Prime Number, Juked, Smokelong Quarterly, Night Train, Pank, Storyglossia, and The Nervous Breakdown. He's also an editor of fiction and poetry at Frigg Magazine.

April 17, 2012

Rooster Slaughter Day, essay by Dena Rash Guzman

Part 1

(I Return In Muck Boots)

Waiting for the slaughter with Ines and her daughter, I have exhausted my Spanish.

They are here to conduct the killings. We are culling our flock.

"Hola. Mi hombre es Dena. Soy un Dena. Mi nino hombre esta Jackson."

Ines wants to know if I speak Spanish. She asks me this in rapid-fire Spanish.

“No.”

“Ah,” says Ines. Ines looks at her daughter. Her daughter asks me something I do not understand. Ines asks me again, for her daughter. She asks me slowly, with fewer words. I still cannot understand.

I try to tell her my son is Puerto Rican and that he is happy to assist with the rooster slaughter. The statement is out of context, in English, and not at all understood. Ines smiles at me.

In Spanish, Ines asks my son’s age. For a moment, I can’t remember. Once I remember, I can’t remember how to say eleven in Spanish, so I hold up ten fingers and then one. In English, Ines says eleven.

Silence comes to silence the little room. We wait for the water to boil so the slaughter can begin. Six roosters are about to die. My first slaughter. Before this, I’ve only seen bugs and one cat die. I look at my hands.

I look at the women’s shoes: Ines in red canvas shoes and her daughter in blue suede sneakers.

I wonder if the blood will stain them. Ines and her daughter are looking at my shoes. They are yellow suede sandals and I know the blood will stain them.

I beg their pardon. I run across the farm into the house.

Part 2

(Language Failed Me and Fails Me Again.)

In shoes that will repel blood splatter, I return to the shed.

Rooster number one, head honcho, is already dead.

I don’t mourn him. He singled me out for the first attack last fall. Many others were attacked by him after me, but he took me first.

He got me by the mailbox from behind, mounting me like he’d mount a chicken and leaving a permanent scar on my back. My third scar ever, only.

I am new to the country. I was a suburban girl. These are my first chickens. These are my first woods, my first closed-in sky, my first rainforest. I had no bearing. I asked why.

Did he think I was a chicken? A coyote? Another rooster?Did he know I said I thought he moved like an insecure Mick Jagger?

“Yes.”

Rooster, strut no more.

The chicken yard is a war zone when there are too many roosters. They rape like it’s a war crime.

Bosnia. Congo. I can hardly look. They don’t stop. They mount and mount, leaving bald spots and scars on the backs of the female chickens.

I think of the poultry world, in which birth control means killing the men or smashing eggs or slaughtering hens. I think of the human world. I think, “We all are made of stars.”

One down.

I’m less relieved and more saddened when the big, sweet, golden one goes. Ines takes a broom and places his neck beneath it. She steps on the handle on either side of the neck. She pulls the rooster’s body away from its own handle-trapped head until the rooster stops screaming.

Snap. He slowly stops flapping. He has stopped his fighting.

Two down.

Three.

Number four, the rooster that looks like a turkey vulture, doesn’t die right. The broom doesn’t snap his neck. It kind of injures it and there is blood and the rooster screams. Panic fills the the shed. We don’t want the roosters to suffer. This is an organic farm. We have to kill them to protect the flock but we don’t want them to suffer any more than their fate strictly requires. His neck is somehow placed back under the broom despite his writhing and rallying.

Snap.

Four down. One to go.

The fifth one gets away–he’s lively. He’s small. He’s the son of the son of a gun that jumped me. They look nearly exactly alike, but Junior has far more spirit. The three of us give chase. I’m no help. The other two corner him. The farmer catches him. The rooster tries to beat him, goes for his eyes. He tries to fly back over the farmer’s head but the long, tall farmer’s arms prevail.

This rooster screams the loudest. Tiniest, but he had the most fight.

Eddie the farmhand says, “Adios, amigos.”

I think, “Too many roosters are not good for the hens. They eat food and don’t lay. They are extraneous. Every good farm has to cull the flock. It’s not barbaric. This is part of raising meat animals humanely.”

I don’t close my eyes or scream. I only imagine myself doing it.

Ines. Broom. Snap.

Five.

It is done. The cleaning starts. The boiling water is used. The feathers are pulled out. Ines and her daughter held the roosters like babies. The farmer did too. I have a photograph of him holding one, and there’s nothing but kindness and curiosity in the farmer’s eyes.

You can’t see the rooster’s eyes. I never looked that day at their eyes.

They held them before they killed them to keep them calm. This was not cruel, this slaughter. It was as humane as it could have been but still, I feel tired and go inside, leaving my son to help clean the feathers and butcher the roosters. He goes all the way. I can barely speak. I have barely spoken at all for the past hour. Feathers and cottonwood drift across the landscape as I walk home.

Part 3

(I finish my wine and feel lucky to be alive.)

I’ve never seen anything but a bug killed before.

We didn’t kill them for food. We killed them for being out of place. We killed the roosters for being out of place, but we will eat the roosters.

The boiling water, the feathers, the broom handle–all in their places now. The blood scrubbed up. The roosters are in bits. Looking in the bag of rooster parts, I can’t tell which rooster is which.

I hope I have at least part of the mean one.

Over at the main farmhouse, they’ve already made coq au vin. I ask my friends what I should make. I look for recipes. I decide on Greek style rooster stew. To make a rooster edible, it must be cooked slowly in liquid. Roosters are gamey, tough things. Same dead as living. I use tomatoes, olives, wine, spices and stock. I talk to my Greek friend and tell her my plan while the rooster is simmering. There are claws and even a neck and head in the stew. If I were to try to make a rooster puppet out of these pieces, it would be a Frankenrooster. There are three thighs, one wing, part of a rib, a neck, a head and three claws.

I don’t think the neck will be edible but I use all of it.

My Greek friend is excited and tells her mom about my dinner. She calls me because her mom says, “Serve orzo.” The stew is on the back burner, simmering on low. I drive the 20 minutes to the nearest town and get orzo. I become addicted to orzo for the next ten weeks.

Dinner time. I wished I had a big triangle to ring. I wished I had a long prairie dress and a long apron. I wished my hair was in a bun like Ma’s on Little House on the Prairie. Hell, I wished I had a fantastic Bono lion’s mane like Pa’s.

I wished I had several kids running in, school books hanging off a leather strap, no shoes because it’s warm out and shoes are for cold weather. It’s not even rained here for a couple of weeks. There’s not even mud. I wished for blue tin plates. I pour the last of the wine into my own little glass.

Several of the farm workers come over. They settle in. They’ve already had the coq au vin and are ready to see what’s next. I serve up peas, Greek rooster stew, green salad and orzo.

My son is served some meaty pieces of rooster, but asks for a foot and the neck. He starts trying to bite through the neck. Tim the Woodsman, who lives back in the groundskeeper’s cottage and fixes everything from the greenhouse glass to airplanes, goes sentimental and speaks of his childhood on a farm in the midwest, eating rooster and rabbit and of the wonderful things his mother did with winter squash.

Rooster is all muscle, high in protein at any rate, and our roosters were truly free range. They had never been in captivity of any sort. They had foraged, wandered and battled coyotes their whole lives. They were champions of the flock. Necessary but in the end, expendable.At night they slept in one of the unused greenhouses or roosted up on the second floor balcony of the farm’s old administration building.

The men exclaim over the flavor of the sauce, but no one really likes the rooster. My son and his father claim to, but they look stoic and hardscrabble trying to chew the meat. I stewed it for hours and still, it didn’t precisely melt off the bone. It’s free range rooster. It’s nothing like a frozen chicken breast.

I listen and take in their silence and interest. This is the first time I’ve ever watched roosters and chickens live and grow. They came from eggs laid on the farm. I saw each of them as a baby. I saw them before we could tell their sex. I saw them mount and menace the flock, and felt one mount and menace me.I helped round them up early on, when they were little, crying “Chick, chick, chickens!” Then I helped kill them, and cooked them.

I can’t bring myself to eat the rooster. Maybe next time. The chickens are not pets, because you can’t eat your pets, but my attachment to them boils over, and I detach. I look around me at all these men and think of them being culled. I rear back, shaken.

That’s enough for one day.

April 14, 2012

Prairie, fiction by Ben Werner

His team had won the state championship and after the celebration on field petered out and the lights atop the poles had clunked off for the last time, he went to the party. Picked up Bre on the way there, and as soon as she was inside his truck she gave him a tongue-thick kiss, grabbed him around his neck, and then pulled away.

“You’re all wet,” she said. “Why are you wearing your jersey?”

“We just won state,” he said.

“Gross. My hands are covered in old sweat.”

“Sweat of a state champion linebacker.”

“I bet all of you are doing it, huh?”

He didn’t answer.

“God, you boys think football is the whole world, even after it’s over.”

He said nothing.

“Well, I guess it’s only for one night. Anyway, we’re state champs!” She laughed and leaned over and kissed his cheek. He smiled. Wind blew ripped sheaves of clouds across the stars and moon and braced against his truck, tipping it at an angle against worn springs.

He parked beside the barn in the dirt lot crammed with cars and trucks. Bre ran ahead through the cold wind and he walked, his shadow blurry and indistinct in the moonlight. He opened the door of the barn to the faint organic tang of manure and climbed the ladder into the hayloft where everyone was gathered, immediately filled two cups with beer, drank and refilled. Swung on the rope swing and slapped hands and hugged. Got drunker and hung his arms around jerseyed shoulders while talking about the game, past games. Drank more and fell down the ladder and puked outside, returned and poked Bre’s ass with his finger and laughed when she hit him softly. Took off his jersey and jumped bare-chested in the crusted-over snow bank on the north side of the barn.

“This is it,” someone said. “We did it.”

People left or passed out and he bit Bre’s lip, felt her moan in his mouth. They climbed down the ladder and stumbled through the dust to a horse stall partially filled with hay bales and he jerked her pants down and pushed his fingers inside her, listening to her surprised, pleasured gasp.

“When I was complaining about your sweaty jersey,” she said, breathy, “I didn’t mean it. I like it.”

The next afternoon he met with a group of seniors at the base of the old water tower, their eyes bloodshot and faces wan and tight. He climbed the steel rungs, bucket of black paint in hand, wind scouring the prairie and blowing up the cuffs of his pants and under his jacket. The town below him set out in pale squares, whites and reds and browns and the occasional flush of evergreen, and beyond it corrugated dusky fields and unfarmable gray swaths.

“I have to study for the ACT,” Bre had said.

“This happens once a lifetime.”

“Go paint the tower, have fun. I can’t. I have to get a 28.”

He and the others painted the tower’s peeling white surface, a math-clubber named Orin measuring and outlining the letters so it would be legible, the wind a constant howl cutting his face raw. The gray sky coughed a few tiny spherical flakes which the wind hurled against his jacket like bits of Styrofoam. When they were done it said STATE CHAMPIONS 2006. He held his empty paint bucket over the railing and dropped it, watching as it fell and hit the crinkled blanched grass below, the lid popping off with a metallic ping.

Back on the ground he looked up at the tower but the large letters wrapped around its curved surface and all he could see was TATE CHAM. He clunked his truck into gear and drove to the bowling alley.

They sat around a fake wood table, multi-colored clownish rentals still on their feet, and watched the regulars tip and waddle around the place. Laughed at their wrist guards, their concentration on form as they whipped the ball down the lanes, their potbellies and tit-sag. Lighting one cigarette off another, Budweiser crimped between two fingers, bellowing at each other as the pins crashed and the owner scolded them while she gathered empty bottles.

“That one could fit a bowling pin up her twat and not even notice,” one of his friends said.

“Forwards or backwards?” another asked. They laughed.

“Can you imagine?” a girl said.

“No. No I could not imagine a bowling pin backwardly rammed up my hypothetical twat.” They all laughed again.

“You’re so immature,” the girl said. “I mean can you imagine being here, like that? Do you see how this is the highlight of their lives? Saturday night at the bowling alley, getting drunk and forgetting their lives blow. It’s fucking depressing.”

“Maybe you should pull the bowling pin out of your ass.” More laughter. The girl lit a cigarette and waved the smoke away from her face, ignored them.

“None of you noticed but Orin fucked up the water tower,” he said. “The letters are too big. He didn’t stack the words. In order to read it you have to drive around the whole fucking tower.”

“Man, everyone has a bowling pin shoved up their ass tonight.”

“Fuck you guys,” he said. “Let’s get out of here.”

They piled into a couple trucks and drove back to the barn where they sat on the naked boards of the hay loft and played cards while they drank. He got drunk and forgot the rules of the game and the others made fun of him, frisbeed cards at him, and after awhile they were all too drunk to play. He called Bre to pick him up but she didn’t answer. It was three in the morning.

He woke shivering on two hay bales and walked down to his truck in the blue-gray of early dawn and drove home where he sat, unable to sleep. Nothing was moving in the morning, the scrub Russian olive trees along the edge of the yard hunkered in gray twisted silence, no birds aloft in their branches, no wind or cloud, not even a dog yip or diesel grumble, nothing but dawn stretched tight in the sky and hardpan prairie. He climbed into his truck, an old listing Chevy, the tailgate tied up with bailing twine and the engine filmed with dark gunk, but still turning the tires, still running good enough. He backed out of the drive of his parents’ house and headed southward.

No wind on the prairie either, which was abnormal of fall mornings when it often whipped shingles off roofs, pried slats from fences, uncorked fifty-foot ponderosas from the lawn at the courthouse. He drove the tar-patched two-lane and outside his window it was always dry yellow cheat and silver clumps of sage and the occasional rusty slice of bare dirt. Way west were silhouettes of mountains, soft and thin and as tangible as dreams. Inside his head was a thud accompanied by a staleness along his tongue and teeth and a hollowness in his body, the remedy for which he pulled damp and brown from a can and tucked in the trough of his lower lip.

He drove with no destination, radio long busted, hangover limping back to where it came from, barbwire fences sewing the ground on either side of him. A dirt road kicked off to his left and he took it, jackhammering over the washboards out into the badlands. Less plant life out there, mostly crusted dirt bands of cream, lavender, crimson, hard cracked country mottled with gritty scabs of snow left over from the first storm of the year. His road curled up a bluff and past an oil pump and then down into a shallow basin where more pumps dipped and rose in steady silence. A faint sulfurous stench sat in the air and he wandered the web of two-tracks around the wells. To the north on a gravel and concrete pad a new well was being drilled, the white and red scaffolding of the rig standing above the prairie and the men on the deck small dark shapes punctuated by yellow hardhats. He turned back towards the main road and even as he left the oil field he could see the rig in his mirror, higher than all else, and he was unable to shed the last aches of the hangover from his body.

Back north then, reflector posts clicking by, dash lines jumping into the square hood, still no drop of wind or fleck of bird, just flat frying pan sky and shriveled prairie.

Eternal tarred coffee cup full of black spit, loose bolt rattle somewhere in the door, rasping bearing, pores leaking malt liquor, infinite Wyoming everywhere.

A brown animal scuttled across his lane and into the other and he swerved at it, hit it with two quick bumps, and slid to a stop on the rumble strips and gathered dust on the side of the road. He walked back to where the animal should have been dead on the asphalt but it was gone. He looked in the weeds on the edge of the road and saw nothing at first, but then, movement in the barrow-ditch between a crumpled sage and bed of prickly-pear cactus, a maimed badger. The thing was a mess of brown blood and fur but its eyes registered him and it let out hisses and growls, still very alive and owning a mouthful of wet teeth, though the back half of it was smashed by his tires. He pitched a rock at it and it humped and snarled and dug at the ground with its front paws, dug hard and fast and with ferocity which showed there was much between it and eternal darkness, coyotes, hopping gangs of crows, worming fly larvae, twisted hide and dust.

God-damned thing would get there though, and he snaked his belt from his pants. Four feet of wide leather with a brass buckle like Hell’s doorknocker. He eased closer to the animal and it watched him and dug at the ground again, setting the sagebrush atremble, and he swung the belt in a circle and brought it down like he was splitting log. The thing screamed and tried to get at him and he swung again and it hissed and wailed in the dust and he thumped it again and again, and still it tried after him, bloody and froth-mouthed and red-eyed. He went back at it, his belt slicing in arcs and the prairie filled with tortured screeches. Thing not dead still, he strung his belt back into his belt loops and retrieved a tire iron from under the seat of his truck. Parts of the animal were speared in sticky clumps on the cactus spikes and others were pounded into the dirt, but still it looked at him and coughed and opened and closed its mouth. Its last breaths interrupted by the muffled crunch of iron on bone.

Ben Werner lives and works in Cody, Wyoming, and is going back to school in the fall.

Fried Chicken and Coffee

- Rusty Barnes's profile

- 227 followers